Keep Giving Signs

Robert Frank’s Letters to Chester Pelkey

In 1981 Robert Frank travelled with his wife June Leaf to Saskatoon, where he showed films and talked about his work at an artist-run space called the Photographer’s Gallery. The night before his talk, at a casual dinner in his honour, he met a writer named Chester Pelkey and they immediately found common ground. June Leaf returned to New York after the talk, but Robert wanted to visit Charlie Murphy, an artist friend from Cape Breton who was teaching in Pukatawagan, a remote First Nations community in northern Manitoba. Getting there from Saskatoon involved five and a half hours by car to Flin Flon and then six and a half more hours on the short-line Keewatin Railway. Chester Pelkey was game, so he, his brother-in-law Ian Francis and Robert set out in a 1966 Valiant heading for Pukatawagan. They took whatever clothes they needed in plastic garbage bags. At one point early in the four-day-long trip, Robert, who was sitting in the back seat, is reported to have rolled down the car window and exclaimed, “On the road again.”

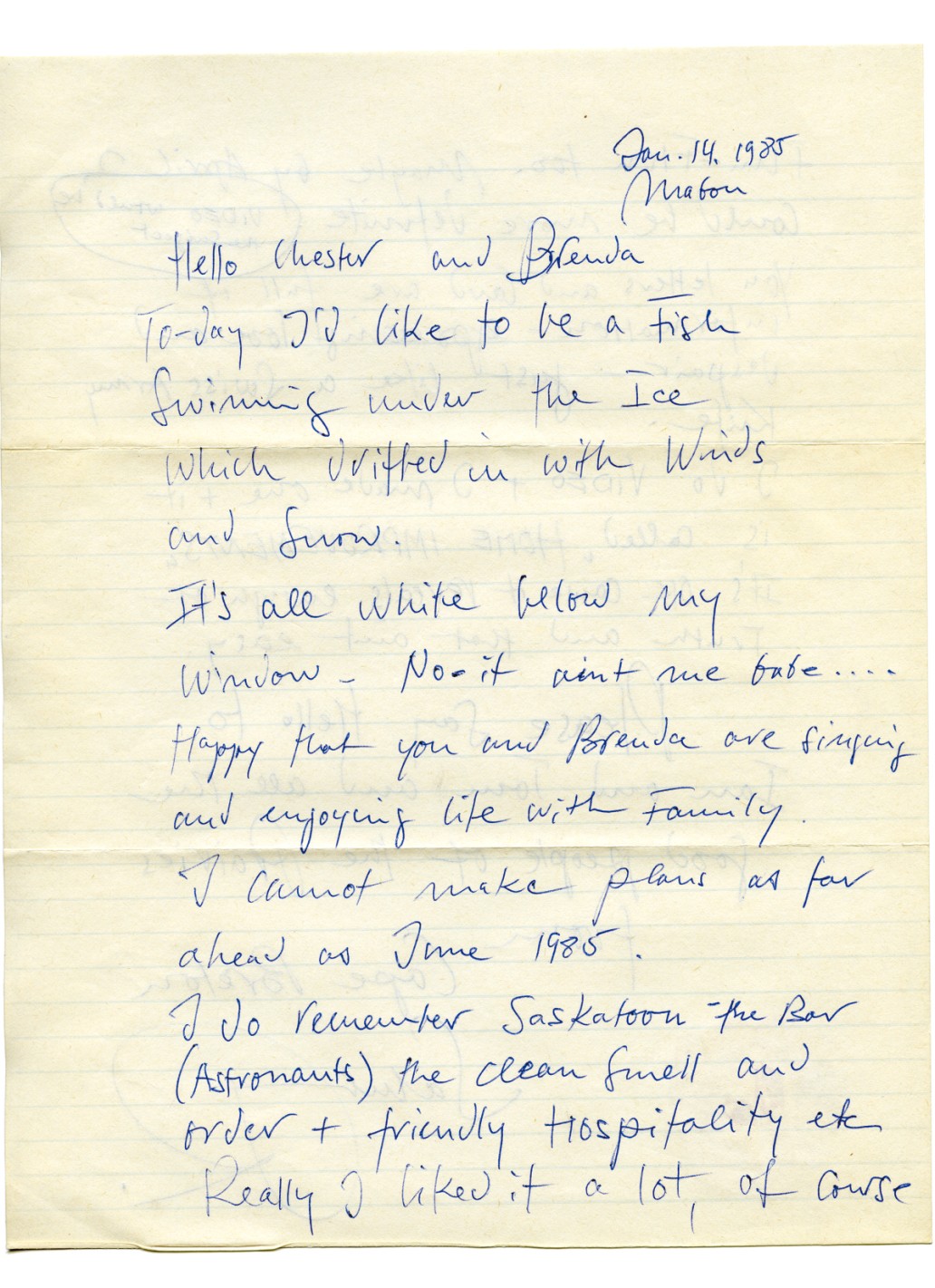

Robert visited Saskatoon once more in the fall of 1985. He gave another talk, this time at the University of Saskatchewan, and he and Chester spent a little more time together, but for the most part their friendship was conducted by phone and through a correspondence that began in 1982 and continued for 25 years.

The 23 letters, four postcards and notes and seven Polaroids that I have seen represent only Robert’s half of the correspondence, but from their content and tone it is evident that one of Pelkey’s persistent subjects is his own debilitating health. Robert often picks up the question of physical decline and adds some complaints of his own. In October 1986 he writes, “June and I fight to keep healthy. Yes, I know it is a loosing matter just prolonging the struggle” (Robert’s spelling, spacing and punctuation are clearly his own and I have no interest in sic-ing the letters, especially when he does things like spelling “typhoon” as “Taifun”).

Two months later he is counting and noting the colour of the pills he is taking: “I sure feel that the end could be near.” But when he wants to register his darkest thoughts, he turns to an old friend. “Kerouac used to say—when asked what are you doing I’m fighting decay,” he writes in a letter dated March 28, 1998. Six years later he thanks Chester for the gift of a first edition of On the Road and remembers the catalytic effect Kerouac had on the people around him and contrasts it with his current physical and psychic state: “I wish I could be clear & happy & feel good but decay is unrelenting.”

The other tension addressed by the letters is the effect of his place of residence. “Back and forth keeps me going,” he writes from Mabou in 1987, but he has a clear preference. New York is “a murderous labyrynthe” in which your choices, as he writes in December 1991, are reduced to “Trump or crack.” Cape Breton, conversely, is a paradise where “I become human again, love my neighbors.”

In this connection, the letters are also a record of his constant search for ideas. The most touching description of his self-doubt turns up on the back of a postcard sent on June 21, 1997. The front shows van Gogh’s Emperor Moth, 1889, and on the back he mentions June’s successful show in NYC (the letters are full of references to June’s working every day and the positive reception of her exhibitions). Then he goes on to present his own creative deficiencies: “Up-stairs I have empty moving screen waiting for images.” At the bottom of the space he has sketched in a blank projector screen with his name written in the centre. He has drawn an empty self-portrait.

In the midst of all the darkness he repeatedly asks for what he calls “a sign of life.” Many of the letters and cards are sent at Christmas and into the New Year, a traditional period of optimism. They are full of good and hopeful wishes. On January 2, 2000, he sends a pair of Polaroids held together by black tape. The top image includes a woman’s eye, small figures of a Mountie and an Indian, and the word “souvenir” written in loose red ink. The lower image gives the piece its name: SNAKE IN THE WELL. “Things here OK waiting for spring—no ice on the water yet. Some good days and nights. Still have a few ideas left chop a lot of wood. See few humans—develop friendship with certain crows.” It couldn’t get any better: anticipating spring, some ideas, physical activity, isolation and his familiars, the ubiquitous crows. Then he signs the image as a way of reminding Chester and his family what he has just done: “Keep giving signs,” and his closing opens everything up.

I want to thank the photographer Brenda Pelkey, Chester’s former wife, as well as her daughter, Nadja, an artist and university lecturer (who, along with her sister, Naomi, owns the letters), for their help in providing information about the friendship between Chester and Robert Frank. There is one other friendship that has its origins in these letters. In August of 1997 Robert writes about the arrival of “the Winnipeg couple” the following day. That couple was Meeka Walsh and me. We had come to Mabou to interview Robert for Border Crossings, and that interview was the first of two conversations, a number of articles and reviews that we published about his work in the magazine over the next 20 years, a period that held many visits and exchanges.

The following portfolio is a selection of the letters Robert Frank wrote to Chester Pelkey between September 1982 and December 2006. ❚