June Leaf in Mabou Since 1969

_1100_816_90.jpg)

June Leaf, House, 2022, mixed media on paper, 11 × 14 inches. Photo: Tim Brennan. All images courtesy Emily Falencki and June Leaf.

Most Atlantic Canadians have experienced the visitors’ enthusiasm for the culture and history of this place and have even had it explained to us by such enthusiasts. But unlike these visitors, we know many places in Atlantic Canada are beautiful but still difficult to live in. We love it here despite that difficulty and are patient with others who love with less nuance.

Some visitors and part-time residents experience the seasons of dearth and know it’s hard to be part of a community if you’re around only for the good times. But those visitors or part-time residents who do spend consistent time here can, perhaps, see with more clarity and communicate this in ways that allow us to see this place with fresh eyes. Through their efforts we can learn what we thought we already knew.

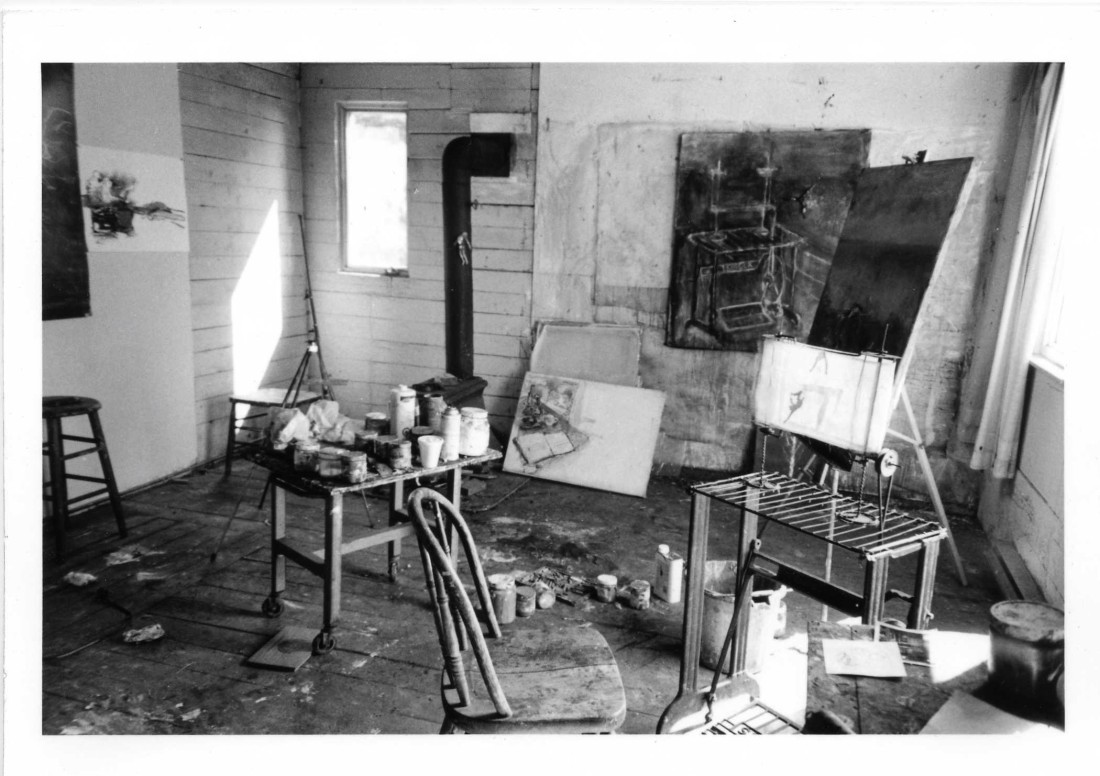

In 1970 June Leaf, the noted American artist, and her husband (photographer Robert Frank) bought a house perched high on a hill overlooking the ocean in a former coal mining village on Cape Breton’s western coast and began splitting their time between New York and Mabou. In 1974 Leaf built a studio in Mabou. That winter, though, she was struggling with both her work and her feelings about Mabou, struggles she documented in a large blue ledger she’d used as a sketchbook (published in facsimile by Steidl Publishers in 2010). Interspersed with her drawings of potential works, of the landscape and, occasionally, community members are raw and heartfelt writings that reflect her doubts and fears over the winter months of 1974–75. “I’ve come to a dead stop,” she wrote on December 6. “Should make a sculpture—don’t want to! Should play the fiddle—don’t want to! Should take a walk. Too cold. Where’s the inspiration? I have built a studio.”

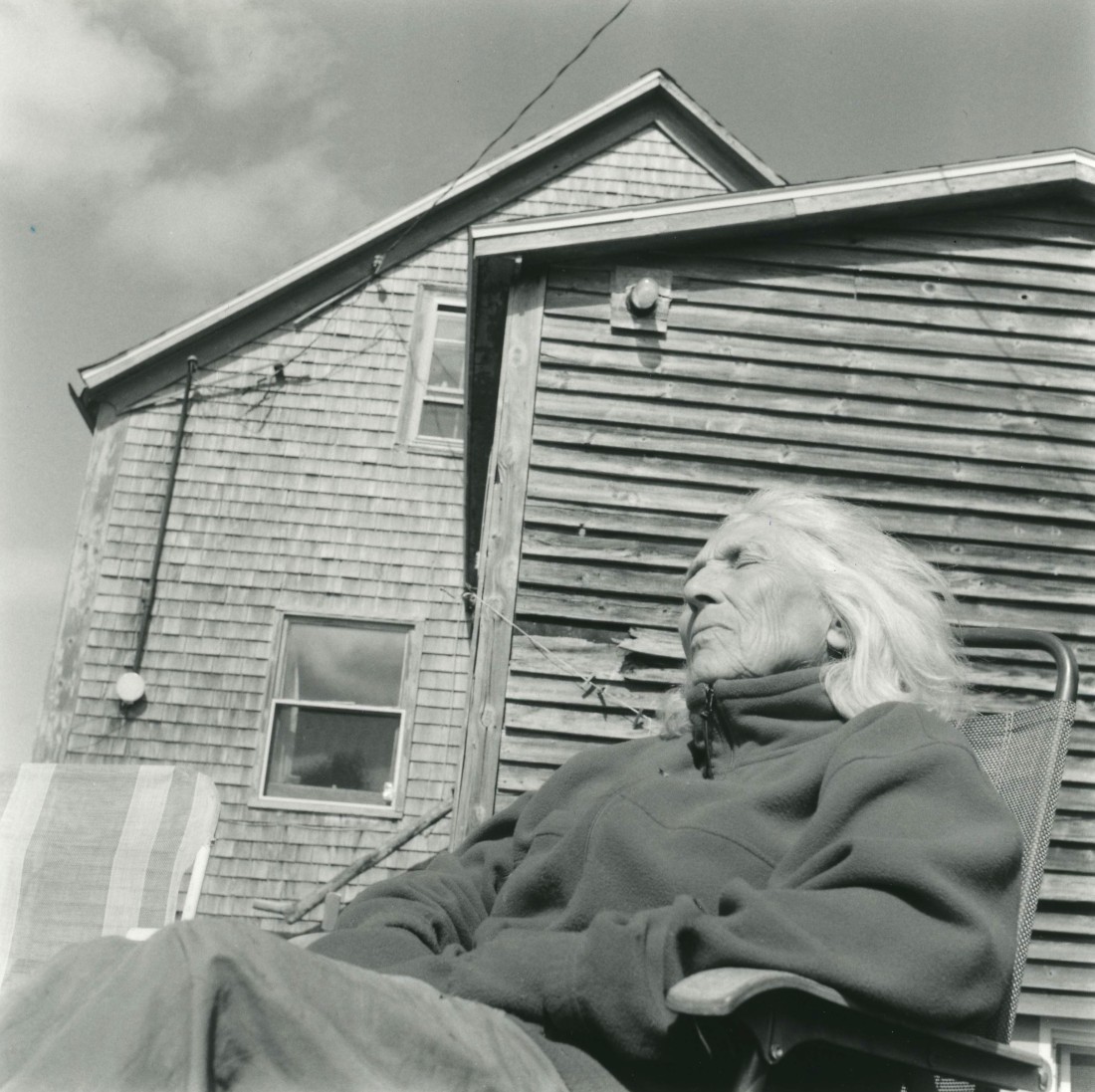

June Leaf outside her studio in Mabou, 2015. Photo: Alice Attie.

Leaf was alone that winter, as Frank was in New York after the death of his daughter. That tragedy heightened the loneliness of what was already an isolated life. Cape Breton that season, for Leaf, was not a tourist destination but “a graveyard.” They would have to leave, she decided. “In almost every way, what I have tried to do here has been impossible,” she wrote. “Nothing can grow here now.”

Forty-seven years later Leaf was seated in the gallery of the Inverness County Centre for the Arts, an art gallery in Inverness, another former coal mining village a little way up the coast from Mabou, surrounded by works dating back to her first year on the island and covering her entire career since then, right up to the present day. Ably curated by Emily Falencki (another expatriate New Yorker who fell in love with Cape Breton), the exhibition is drawn almost completely from Leaf’s Mabou studio, and it made clear that despite those early misgivings, much could grow here: “I experienced the feeling of belonging on the land,” Leaf said recently, “on the world, on the earth.”

Most of the works on view were never intended for public display. They were often scrappy and unfinished, marred with dirt and stains from having been stored haphazardly. These were working documents, preparatory sketches and thought experiments, the products of a restless, voracious artistic mind. They were also documents of a place: the coast as seen from the heights where they lived, the beach where she swam, the hills up behind Mabou. The ocean appears in drawings of boats, often with gigantic figures astride the shoreline or looming over the horizon. Multiple sketches record how she arrived at finished works, her stops and starts stuttering across the pages.

Among these were drawings of the people who made that place. “I decided to do portraits because Robert’s daughter, Andrea, had died tragically when she was twenty in a plane crash,” she recalled. “I was completely devastated. And it was therapy for me to go to the people who knew her and visit them. And then I decided to draw them.” In doing that, she captured something of the community. In Reginald and Chris Rankin, the couple sits at their kitchen table. He stares directly at the viewer; she looks out the window, a somewhat abstracted expression on her face. Leaf depicts their reaction to the strangeness of being drawn, a mixture of discomfort and tension that centres on Reginald Rankin’s seemingly relaxed pose of his forearm on the table.

Leaf wasn’t just surrounded by her work that day in Inverness, she was surrounded by her community. Elderly people looked at images of themselves in their youth, or young people looked at images of great-grandparents they never could have known, all drawn with Leaf’s characteristic swift, strong lines and sensitive use of colour and shade. The mottled surfaces of these often sun-faded sheets spoke to their being valued, but as living objects, not precious items hidden away in museums. “The biggest pleasure to me in the exhibit was when I walked in and I saw the people who I drew,” she said. “They or their relatives were looking at their portraits and that I think is one of the most magical moments of my life.”

Installation view, “June Leaf in Mabou Since 1969,”2022, Inverness County Centre for the Arts, Inverness. Foreground: June Leaf, Charge, 1980, bronze, 32 × 16 inches. Photo: Emily Falencki.

The Mabou Giant, 2022, mixed media on paper, 30 × 34 inches. Photo: Tim Brennan.

A palpable presence in the exhibition was Leaf’s late husband, Robert Frank. He is the subject of some works in the exhibition, as in the 1975 collage Robert Carrying Wood, which features a snapshot of Frank pasted into a landscape drawing of the view from their house. A metal mask, installed in the middle of the back wall of the gallery, is undoubtedly his portrait, with ragged cuts in the metal along the top edge recreating his flyaway hair. But Frank is present in more than just images. It was his influence that brought Leaf to Cape Breton, though they responded quite differently to the place. “All the silence and emptiness here is some kind of medicine for him,” she wrote in January of 1975. “He wants to be a man on a hill looking at the ocean—it is a picture in his mind that he wants to live.” Leaf was looking for something else.

The many portraits in this exhibition show, at least in part, that she found what she was looking for in the community. She may not have wanted to play the fiddle, but she did want to depict the people who lived in Mabou. “The decision I made to try and paint the people in Mabou seems to be a good one,” she wrote in 1975. “At least it has taken me out of that confusing orbit of my endless and unresolved ideas.”

“June Leaf in Mabou Since 1969” makes evident her continuing to paint the people of Mabou, as well as pursuing those endless ideas. To Leaf in her early years there, Mabou was a “foreign land.” But now, she says, “it feels like home.” It is apparent that she is settled there, and that she understands what she wrote about that place decades ago: “life is good, but you must meet it more than halfway.” At 94, Leaf is still rushing to meet that life, distilling unexpected poetry from that beautiful—if often harsh—landscape she has lived in and with since 1969. ❚

Ray Cronin is a Nova Scotia-based writer and curator. He is the author of 12 books of non-fiction and the editor-in-chief of Billie: Visual Culture Atlantic.

June Leaf’s studio in Mabou, 2016. Photo: Alice Attie.

Robert Carrying Wood, 1975, mixed media on paper, 22.5 × 28.5 inches. Photo: Tim Brennan.

June Leaf looking out to sea in Mabou, 2017. Photo: Alice Attie.

Visitor, mixed media on board, 18 × 30 inches. Photo: Tim Brennan.

Reginald and Chris Rankin, mixed media on paper, 18 × 24 inches. Photo: Tim Brennan.

Sally Central, acrylic on canvas, 4 × 6 feet. Photo: Tim Brennan.

Charlie Joe MacLean, mixed media on paper, 18 × 24 inches. Photo: Tim Brennan.

Untitled, metal, 11 x 8 inches. Photo: Tim Brennan.

View Finder, mixed media, 10 × 12 inches. Photo: Emily Falencki.

June Leaf in her studio in Mabou, 2017. Photo: Alice Attie.