Jimmy Limit

For a while, as I drive from Toronto to St. Catharines along the Queen Elizabeth Way, I tail a customized vintage compact pickup. The roof of its aluminum bed cap is blue, matching the blue letters on its tailgate that spell CHEVROLET. From the right of its chrome bumper dangle what might well have been no more than a plastic bag containing two tennis balls, but appears like a synthetic blue scrotum. The coincidence of this sighting in advance of a visit to an exhibition of Jimmy Limit will soon be apparent. Its relevance, however, is not so much how the art of Limit, and so many other artists of the moment, reflects vernacular form, impulse and irony, but a reminder of just how personal that art actually is.

Jimmy Limit, “Recent Advancements,” 2014, installation view, Rodman Hall Art Centre, St. Catharines. Photograph courtesy Rodman Hall Art Centre.

The other incidental fact of my gallery visit is that it occurs on the final day of a 15-week run. A number of the works contain organic matter—grapefruit, oranges, lemons—that has desiccated considerably since the opening. I will encounter the sculptures at the shrivelled end of their site-specific shelf life. Fortunately, Limit has foreseen the gradual fading of the vivid citrus skins. A framed photo of the pristine installation hangs across from the front desk at Rodman Hall, just before you would turn left through the threshold into the gallery it portrayed. It is easily bypassed without being noticed. This portrait, devised by the artist, not the venue, not included on the checklist, occupies an ambiguous status between artwork and promotion. The generic, codified and refined portraiture industry of utilitarian products for brochures, catalogues and websites, many browsed exclusively by the pickup-truck demographic, deeply informs Limit’s aesthetic.

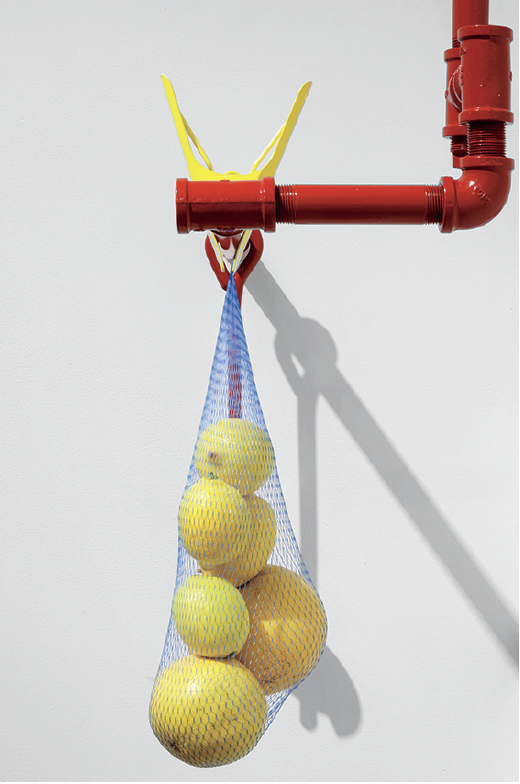

Most of the items from which Limit constructs or assembles his sculptures or puts on almost raw display were ordered from such catalogues, often with no more modification than a powder-coated application of bold, monochrome pigment. They bear such titles as Chandelier Extender and Work Surface, Multi-Purpose Display Rack [citrus, etc.], Red Water Pipe with Hanging Citrus [lemons, grapefruits, nutrition, refresh, recline] and Jimmy Limit x Strömby (The last refers to the IKEA product name with which the 17-part, mural-like series of small, matted photographs are framed.) The water pipe emerges from and disappears back into the wall in a corner of the gallery, as if it might be a permanent appurtenance of the room, like a fire-extinguisher, even more so (as if built in) and less (to be hereafter ignored). Casually placed around one of its joints is an apple-green, powder-coated length of mangled steel rod, looking like one of Ai Weiwei’s retrieved earthquake re-bars before being pounded back straight. On another section, a yellow metal clip pincers a blue mesh produce sac full with now dull, dry fruit. Looped round yet another spot along the same horizontal length of pipe hangs a red metal pendant of unknown purpose, but purpose it does indeed emanate, which, being the same colour as the pipe, practically disappears from the equation of additive intention.

Red Water Pipe with Hanging Citrus (lemons, grapefruits, nutrition, refresh, recline), 2014, powder coated metal pipe, mesh bag with lemons and grapefruits. Courtesy Clint Roenisch Gallery, Toronto. Photograph: Jimmy Limit.

The exquisite interior details of the early Victorian Rodman Hall—parquet floor, baseboards, fireplaces, dentition and ornamental foliate plaster on the ceilings—rim the salon galleries and yet have been visually trimmed back, disappearing into a neutral white latex paint treatment typical of contemporary art spaces. Limit teases out these elements and beautifully coaxes the highly hospitable, near symmetrical proportions of the rooms, so that his sculptures, for all their anonymous composition, acquire figurative, almost sentient, certainly domestic attributes. Thus Limit’s inclusion of photographs of other sculptures that are part of the genealogy of his practice fits right in, like pictures of relatives and the immediate family when everybody was younger. One of these pictures hangs half-hidden behind a door. A found cyanotype, Venus [Seopas], from the Temple of Aesculapius, Athens, c. 1900, becomes a talismanic classical prototype. A homely work, Forgotten Floor Paint Can, powder-coated apple on its outside and dark within, containing a circular blue foam pad and a tarnished orange, is like the family pet, a well-behaved mongrel that unobtrusively occupies a quiet corner.

“Recent Advancements” is replete with such alert details. And this is not even the half of it. The sculptures, indeed all the works, are each sturdy, distinct and convincing in their own rights. One of the most ingenious is Lemon Funnel Still Life [3 views], a Georges Braque-like, post-cubist still-life sculpture comprised of a rectangular yellow board floor base, from which stand two narrow yellow posts, atop which is nailed a plain, square, white tabletop. The table supports a bowl of fruit, as such, that is a black vinyl funnel jammed into an apple-green pipe flange, within which are five lemons. The sculpture is centred in a generous semi-octagonal niche at the back of the room, each of three walls behind it applied with a rectangular matte monochrome backdrop, yellow, blue or grey, so that by choosing one’s perspective, one momentarily transforms the sculpture into a preferred vision of a painting. ❚

“Recent Advancements” was exhibited at Rodman Hall Art Centre, Brock University, St. Catharines, Ontario from January 18 to May 4, 2014.

Ben Portis is a curator living in Toronto.