Jean-Michel Basquiat

Visitors hearing the rousing yet melodious voice of Martin Luther King Jr via a blaring audio recording of his touchstone “I have a dream” speech and then spotting prominent Jay Z quotes will know that Jean-Michel Basquiat: Now’s the Time is framed hyperbolically as a Black exhibition. However, Basquiat’s urban naïve art references Dubuffet before Malcolm X. Recalling a grad school critique of racial hegemony, the didactic text states, “Basquiat challenges Western history by creating images that honour black men as kings and saints.” Conversely, Basquiat’s faux-childlike portrayal of these heroes renders them more as a young black man’s mentors than as an activist’s icons. After all, Basquiat was a mere 21 when he was exhibiting his work in now historic exhibitions, including the “Times Square Show,” “New York/New Wave” and “Documenta VII.”

It is easy to cast Basquiat strictly as a Black artist, given such historic imagery and his many references to racism and violence. Example: painting of a fellow graffiti artist who died while in police custody (The Death of Michael Stewart, 1983) and metonymical allusions to slavery with the word “cotton.” Even the usually reliable New Yorker critic, Peter Schjeldahl, cast Basquiat as “a soft young African prince.” In fact, Basquiat’s mother was Puerto Rican and his father Haitian.

Basquiat’s sobering racial politics were certainly welcome amidst the hedonistic ostentatious New York art world of the early ’80s; nevertheless, his streetwise yet jarringly personal drawing and painting is what inspires viewers, many generations of identity politics later. His candid expressionism was wrought with an electric, dancing and achingly anxious line, the line of a talent in no need of art school training, a line that his greatest supporter, the poet Rene Ricard, and detractor, the critic Robert Hughes, could both agree showed driving, compelling energy.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Obnoxious Liberals, 1982, acrylic, oilstick and spray paint on canvas, 172.72 x 295.08 cm. Photographs: Douglas M Parker Studio, Los Angeles. Courtesy Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, and The Eli and Edythe L Broad Collection. © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Images licensed by Artestar, New York.

The exhibition’s guest curator, Austrian art historian and curator Dieter Buchart, a Basquiat scholar, possesses an astute formalistic comprehension of Basquiat’s work, well-revealed by his prior exhibition of it with Cy Twombly’s and Egon Schiele’s paintings (“Deep Space,” 2012, Nahmad Contemporary, New York). Indeed, Basquiat shared Twombly’s loose, graphic brushwork and Schiele’s penetrating expressionism and prolificacy. By carefully editing Basquiat’s often tired, formulaic later work, Buchart has assembled, without sacrificing quality, an astutely edited yet encompassing exhibition of nearly 85 large-scale paintings and drawings chronicling Basquiat’s career span.

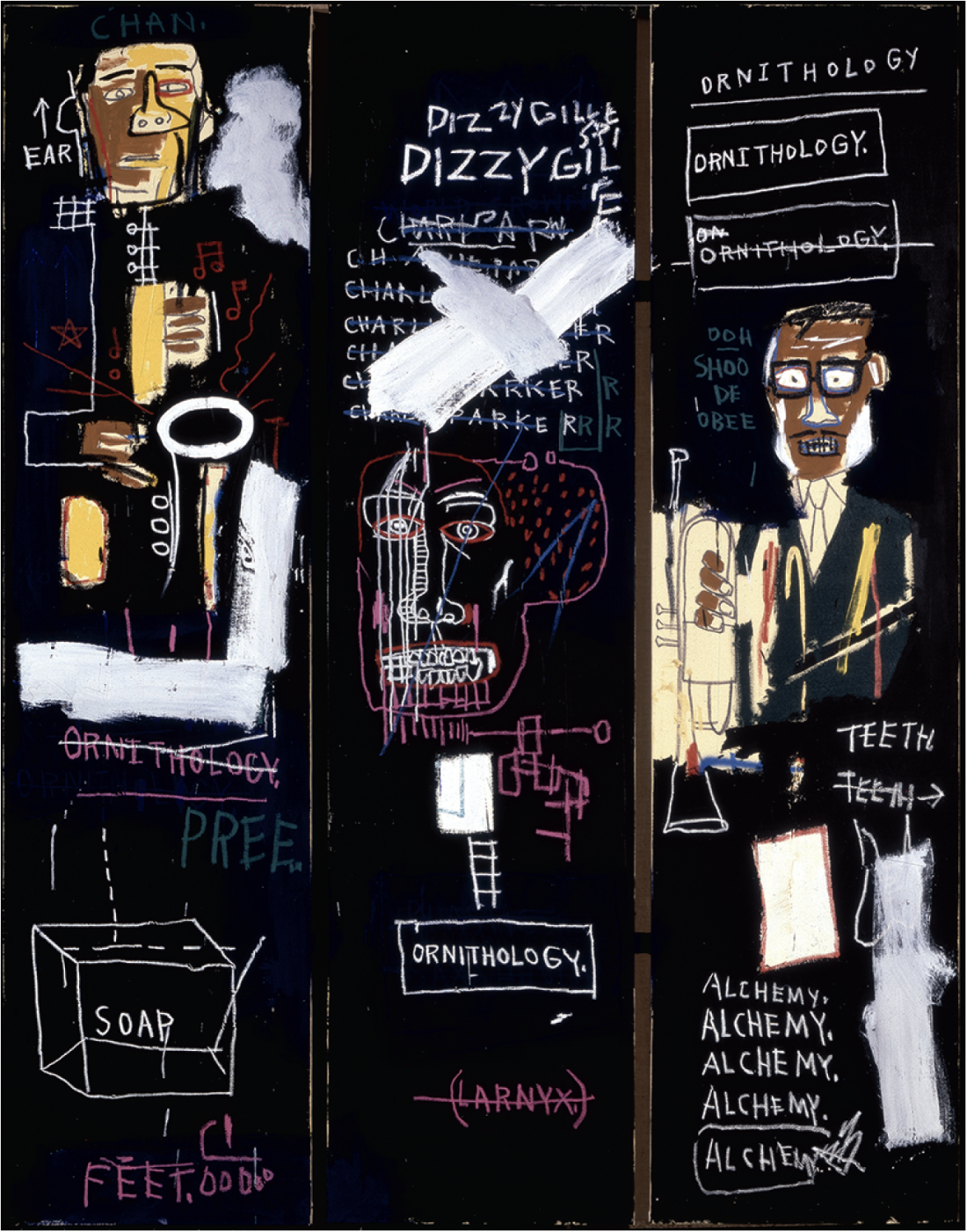

In Basquiat’s best work language merges with line—a cross-pollination of Pollock’s jazz- and liquor-fuelled action painting with automatic writing. Jazz influenced Basquiat too. Jazz players, amongst his childhood heroes, frequently appear in his paintings; for example, full body portraits of Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker define Horn Players, 1983. Basquiat’s scratchy, jumpy delineations outline these figures in nervous if not neurotic tension. Should these icons not be confident heroes? Here, however, they evince an underlying anxiety and vulnerability.

“Charlie Parker” is written repeatedly only to be painted over with rough criss-crossed brushstrokes loaded with white paint, a self-redacting technique Basquiat introduced in 1981, early in his career. Such deletions reflect his fascination with jazz improvisation by favouring process-revealing spontaneity over the pre-planned, polished end product. Simultaneously, crossing out words implies self-consciousness and self-censorship. Read psychoanalytically, Horn Players is not a portrait of icons but a self-portrait that symbolizes the long leap from insecurity to achieving the public reverence Parker and Gillespie received. Recall that Basquiat was notoriously ambitious; when still unknown and maintaining a park bench as his primary residence, he famously approached Warhol who was dining with colleagues at an upscale restaurant, to show him his work.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Horn Players, 1983, acrylic and oilstick on three canvas panels mounted on wood supports, 243.8 x 190.5 cm. Courtesy: Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, and The Broad Art Foundation. © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Black American culture was pivotal to Basquiat’s identity, and his art reflected that autobiographically. Also consider Oreo, painted in 1988, the year Basquiat died. In the centre of a green monochrome ground shines a bright white circle with a scrawled black outline. A cross shape rises from the circle like a grave marker. Oreo, referring to the black-on-the-outside, white-on-the-inside individual assimilated into White society, again reads politically but only through a personal filter. Tragically, it stands as a prescient epitaph of Basquiat’s own design, a requiem for his carried-to-the-grave guilt over rising to the crest of fame in a whitewashed art world.

Basquiat painted Oreo when personally and artistically wreaked by a confluence of worsening addiction and unbearable market pressure to produce work (at the time of his death 35 dealers sold his inventory of over 2,000 drawings and 1,000 paintings). His dwindling energy had snuffed his earlier works’ graphic dexterity, leaving a flat plane of colour alone to carry the painting (colouring-book reminiscent space filling was Basquiat’s greatest technical shortcoming). Only a few later works alongside Oreo complete the exhibition timeline; Buchart rightly focused on Basquiat’s strongest work from 1981 to 1985. The exhibition’s skewed contextualization notwithstanding, “Now’s the Time” accurately portrays Basquiat as an artist whose later lapses did not mar his continuing significance. ❚

“Jean-Michel Basquiat: Now’s the Time” was exhibited at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, from February 7 to May 10, 2015.

Earl Miller is an independent art writer and curator residing in Toronto.