Jack Goldstein and Ron Terada

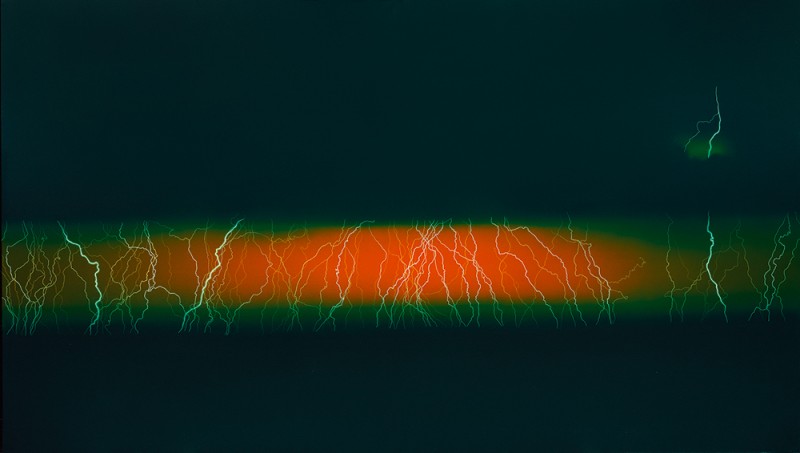

Jack Goldstein, Montreal-born but residing in the United States most of his life, has received few Canadian exhibitions despite international acknowledgement. Consequently, “Jack and the Jack Paintings: Jack Goldstein and Ron Terada” should be especially welcome in Canada. The exhibition’s title, however, is a misnomer, as it claims to pair equally Terada and Goldstein, when the stress is on the former. In fact, only one of Goldstein’s paintings is exhibited: the monumental (96 x 168 inch) Untitled, 1983, a realistically rendered lightning storm whose slick airbrush-reminiscent aesthetic commodifies powerful nature to distance it from the sublime. The exhibition instead focuses on Ron Terada’s series of 14 acrylic-on-canvas paintings (each titled Jack and painted from 2016 to 2017), that faithfully copy to a larger scale (80 x 64 inches) pages from Goldstein’s 2003 gossipy and tragic memoir, Jack Goldstein and the Cal Arts Mafia.

Terada’s text reproduces the book’s entire 11th chapter, “New York Dealers and Collectors,” which narrates the difficulties Goldstein experienced working with the two. Terada meticulously copied single pages but reversed conventional text colour to white on a black background. With wit he painted the text in the ITC Souvenir font, popular enough in the ’70s to stand emblematic of that era, but falling out of favour in the ’80s, just like Goldstein’s paintings. Goldstein recalls, for example, “Some years later, when I was living in LA and had no money, Michael [Schwartz] took a $35,000 painting and gave me $1,200 for it. He knew I was down and out.” Goldstein no longer effortlessly surfed the crest of the turbulent art market wave.

Jack Goldstein, Untitled, 1983, acrylic on canvas, 243.7 x 427 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of Sandra Simpson, 1993. © Estate of Jack Goldstein.

The chapter recounts how painting cool reproductions of media-inspired or media-borrowed imagery positioned him awkwardly as too old to belong to the media-savvy reductivist neo-geo artists he shared common ground with, but too different stylistically to identify with the more saleable figurative revival paintings of his colleagues David Salle and Julian Schnabel.

Goldstein’s sales dropped to a career-killing level, leading to a personal downward spiral. Just before his 2003 suicide, he was living in a trailer without running water in East LA, in the late stages of heroin addiction, getting by with temporary labour jobs. Yet the chapter Terada copied is important not only for addressing personal tragedy but for revealing the brutal, greedy market that underpinned the return to painting in the late seventies. Terada’s consideration of the socio-economic conditions shaping Goldstein’s art through language functions ironically. Tereda documents the mercenary excesses of the Reagan-era art market by signifying anti-commodity conceptual art through a Kosuth-reminiscent, austere, black and white presentation of text, free of the implied materialism of imagery. Accordingly, viewers can reject the bourgeois commodification of the image at the same time they read snippets of the book’s juicy gossip, discovering which artist slighted Goldstein or which gallerist exploited him. Terada’s ironical text paintings suit a painter grounded in the rigorously theory-based post-conceptual art of his alma mater, Cal Arts, and who later switched to large-scale salon-style painting, flagging his art as collector-friendly in an era of hyper ostentatiousness.

Ron Terada, Jack, 2016–17, acrylic on canvas, 14 panels, 203.2 x 162.6 cm each. Art Gallery of Ontario. Purchased with the assistance of Eleanor and Francis Shen, 2017.

Terada highlights how Goldstein emblematized the art world’s transition from language to painting, from radical conceptualism to marketable goods, as the liberal ’70s became the conservative ’80s. Some of the text Terada chose documents this turn to blunt materialism. For instance, Goldstein recalls, “I paid $20,000 cash for a car that looked like a 1956 Porsche…I also had Corvettes in New York. I used to drive them two hundred miles an hour over the Brooklyn Bridge…” The moneyed art star Goldstein portrays himself as reflects celebrity culture among young New York artists in the ’80s, whom Schnabel exemplified, artists no longer struggling as cash-strapped bohos but thriving as free-spending, cigar-chomping capitalists, a Warhol-meets-Trump paradigm bleakly prescient of today’s overheated art market. In one painting Goldstein recounts being “in a bar with Gagosian, and he told me how he could live off of one Brice Marden painting. He knew when to sell it and when to buy it.” Goldstein’s anecdote fast-forwards us to today’s multiple Gagosian gallery locations across the globe that have made its namesake owner a billionaire.

Paradoxically, this non-romantic market takeover of contemporary art plays into the romantic tortured-artist cliché via Jack Goldstein’s troubled life. Goldstein carries a role more commonly associated with van Gogh, of course, typecast as a mercurial expressionist too far ahead of his times and too sensitive for the world to experience anything but abject misery. Goldstein, the emotionally detached post-modernist, runs contrary to this modernist archetype. Accordingly, Terada argues post-modernism has not demythologized the artist; rather, it has updated the romantic myth to 21st century artists tormented not by indifferent philistines but by exploitative capitalists. “The Jack Paintings” provides a cautionary tale of how the market punishes artists while limelighting collectors and dealers.

Jack and the Jack Paintings: Jack Goldstein and Ron Terada” was exhibited at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, from May 26 to September 16, 2018.

Earl Miller is an independent art writer and curator based in Toronto.