Iconographer of the Local

A Conversation with David Thauberger

David Thauberger has an appetite for making, collecting and looking at art that mirrors the prairie space in which he lives; it’s wide-ranging and moves, unimpeded, in all directions. He is visually omnivorous, a disposition that was planted and grew in the layered art historical soil of Saskatchewan, his home province. Had the poet Robert Kroetsch been an art critic, he would have asked in Seed Catalogue, his seminal poem, “How do you grow a Prairie painter?” The answer: “Plant him in contentious soil.” David Thauberger was in the right place at the right time to become that Prairie painter.

The history of art-making in Saskatchewan is a tale of two cities and one lake. Beginning in the late 1950s, Regina and Saskatoon began to develop competing attitudes about what art should look like and where artists should look for aesthetic models. Saskatoon looked to New York, largely because of the influence of the Emma Lake Artists’ Workshops. Each summer workshop had a leader, and by 1967 that position had been occupied by a notable group of American artists, including Barnett Newman, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski and Frank Stella. Most significantly, Clement Greenberg came in 1962, and his influence was shaping. He was the High Priest in the High Church of Modernism which emerged as Saskatoon’s official artistic religion.

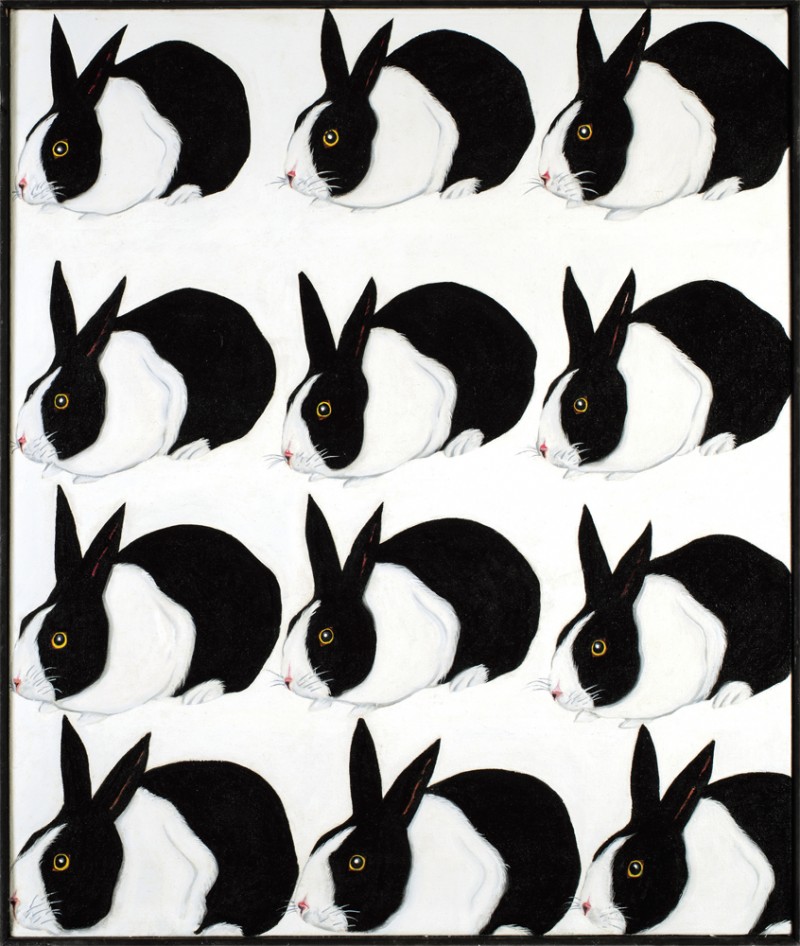

12 Rabbits, 1974, 90 x 76.4 cm. Saskatchewan Arts Board Permanent Collection. Photograph: Don Hall.

The belief system of many Regina artists was very different. Their epiphany came in 1969 when David Gilhooly, a charismatic ceramic artist from California, arrived to teach at the Regina campus of the University of Saskatchewan. As David Thauberger says in the following interview, “He lifted the roof off everything. Gilhooly’s visit changed the whole world for me.”

Thauberger was among the Regina artists who looked for inspiration to California and a group of funk-fuelled ceramic artists like Gilhooly and Robert Arneson. He was also intrigued by painters, Roy De Forest, William T Wiley and Wayne Thiebaud among them, whose subject matter and style were irreverent, pop-inflected and anti-formalist. Additionally, he was attracted to the Hairy Who and the Chicago Imagist movement, and the work of artists like Roger Brown, Jim Nutt and Ed Paschke.

What “Road Trips & Other Diversions,” the touring exhibition co-mounted by the Mendel Art Gallery in Saskatoon and the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina, makes apparent is the city war was more a series of skirmishes than a campaign. In addition to a generous selection of paintings, ceramic sculpture and prints by Thauberger, the exhibition includes a number of works that the artist and his wife, Ronnie, have collected over the years. The choices include works on paper and clay sculptures from both sides of the conflict. Among them is an exquisite lithograph by Frank Stella called Chocorua, 1974. It is a telling choice.

In the interview, Thauberger relates that to get to his art classes at the university you had to pass by a large painting by Frank Stella that the MacKenzie Gallery had purchased in 1967, only a year after it was made. (Stella was the Emma Lake Workshop leader in 1967, which undoubtedly played into the acquisition.) Union II is irregularly shaped, alkyd fluorescent and epoxy paint on canvas, and at 263 x 442 centimetres, it is imposing. “In the low-ceilinged architecture of the MacKenzie it looked like this big structure was literally holding up the whole building,” Thauberger remembers. The painting is an impressive composition in which three colours—orange, blue and green—orchestrate a progression of intersecting geometric shapes, but it likely didn’t appear that way to an art student obliged to walk by it every day. Decades later, that same student-turned-artist added a work by the monster artist to his collection.

Thauberger recognizes that the issues he rejected in the ’60s and ’70s are now important. “I think my paintings are about the modernist idea of flatness. It shows you can’t escape your own experience.” The problem he faced was the enduring and complicated one of finding a pictorial language that reflected the place he lived and that engaged the people who lived there with him. “I was trying to deal with the iconography of the local and with specific prairie things,” he recalls, and finding the language to do that involved hearing the full range of accents in the art he had encountered. He realized the artists he admired in California and Chicago had their own iconographies and while he could have worked with those idioms, they were articulating their own place, as were the New York artists. He had to do the same thing.

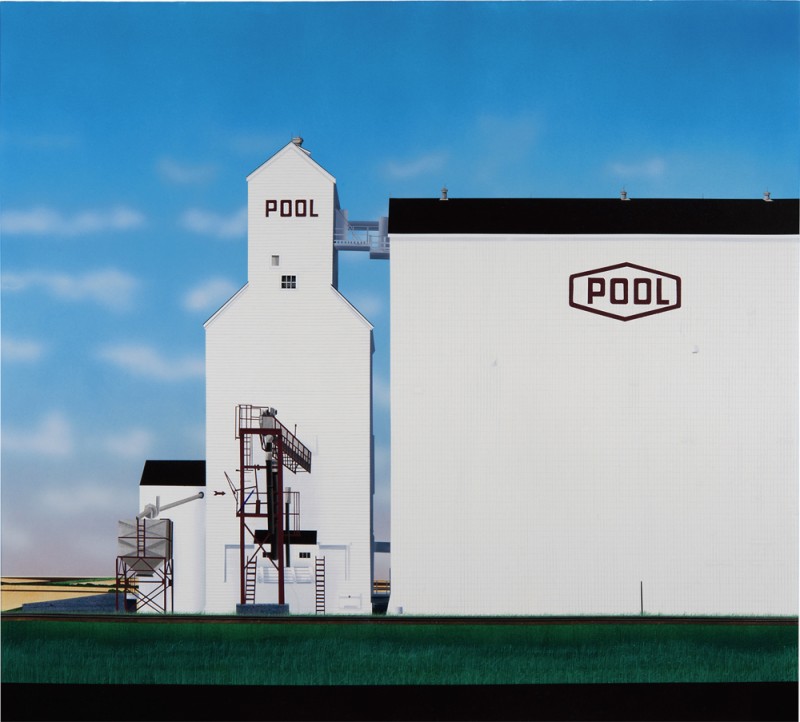

Long Haul, 2000, acrylic on canvas, 162.2 x 177.8 cm. Collection of the MacKenzie Art Gallery.

The way into that conversation came through his relationship with the folk artists he discovered when he worked with the collection of the Saskatchewan Arts Board. “The main thing is they nailed this whole question of being here and making paintings that were from here and about here,” he says. The folk artists were the anchor that held him in place. Thauberger’s art is understandably eclectic; he is as likely to borrow an idea from Ellsworth Kelly, Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol or Jim Dine as he is from Wesley Dennis, WC McCargar, Harvey McInnes or Fred Moulding. He can look as far away as 19th century Europe. On his first trip to France he noticed affinities with Monet and the Impressionists when he saw their work in depth. “I realized these guys were doing the same thing I was doing; they were walking down the road and finding subjects.”

Thauberger makes you appreciate how layered is the idea of place. In his own collection, there is a wonderful acrylic and fibre-tipped pen on Masonite painting made in 1981 by folk artist Ann Harbuz. It is called Across the Country of Saskatchewan. From the flat country she imagines and with his eyes looking in every direction, David Thauberger has produced a lifetime of work that makes all knowledge its province.

The interview was conducted on June 10, 2014 at the Mendel Gallery in Saskatoon where “Road Trips & Other Diversions” was on exhibition.

To read the rest of Robert Enright’s interview with David Thauberger, order Issue 131 or subscribe.