Ian Wallace

The Ian Wallace retrospective titled “At the Intersection of Painting and Photography” occupied the first and second floors at the Vancouver Art Gallery and showcased work from over 50 years of this Canadian artist’s career. Curated by Daina Augaitis, this eye-opening exhibition was accompanied by an illustrated book with texts by nine contributors—essays and interviews, and writings by Wallace himself. The very carefully considered installation positioned the artist’s work in thematic groupings such as The Studio, The Museum and The Street, which, in light of his ongoing artistic commitment to these and other topical categories, allowed a more in-depth examination of specific formal artistic and conceptual investments than a chronological presentation might have done. For example, in The Studio section one could view work dating from his 1983 exhibition “At Work” at the Or Gallery, through work as recent as 2012 from the “Hotel” series, which, as many readers will know, factors into The Studio stream through Wallace’s itinerant professional lifestyle and working habits. Early work in the show in this vein were Untitled (In the Studio with Table), 1969 (released as an artwork in ’92), Image/Text, 1979 and a two-channel video piece titled Studio Work, also 1979; but it was Wallace’s pivotal Or Gallery show in 1983 that is a cornerstone of this series, and arguably represents an important turning point in the history of Vancouver art.

Late night spectators could view the working artist through the Or Gallery’s Franklin Street windows between midnight and 1 AM for the two-week run of the exhibition. It was the image of the artist, who by this time was well known in Canada and abroad—positioning himself as the subject, as the artwork, sitting alone at a modular table constructed of plywood and sawhorses, with paper, pens, books, bottle of wine, writing, reading, drawing—that might be said to have symbolically and conceptually ushered the city, on a local level and particularly amongst emerging artists, into the mainstream of contemporary art. Not that Vancouver lacked a history of conceptually engaged work; far from it. It was Ian Wallace’s stature in the community, as an artist, writer, art history professor and intellectual, his very example now condensed into a short-span, real-time representation, that galvanized young artists and art students to a model of artistic praxis represented by thought, study, planning, reflection and production—the idea of art as research.

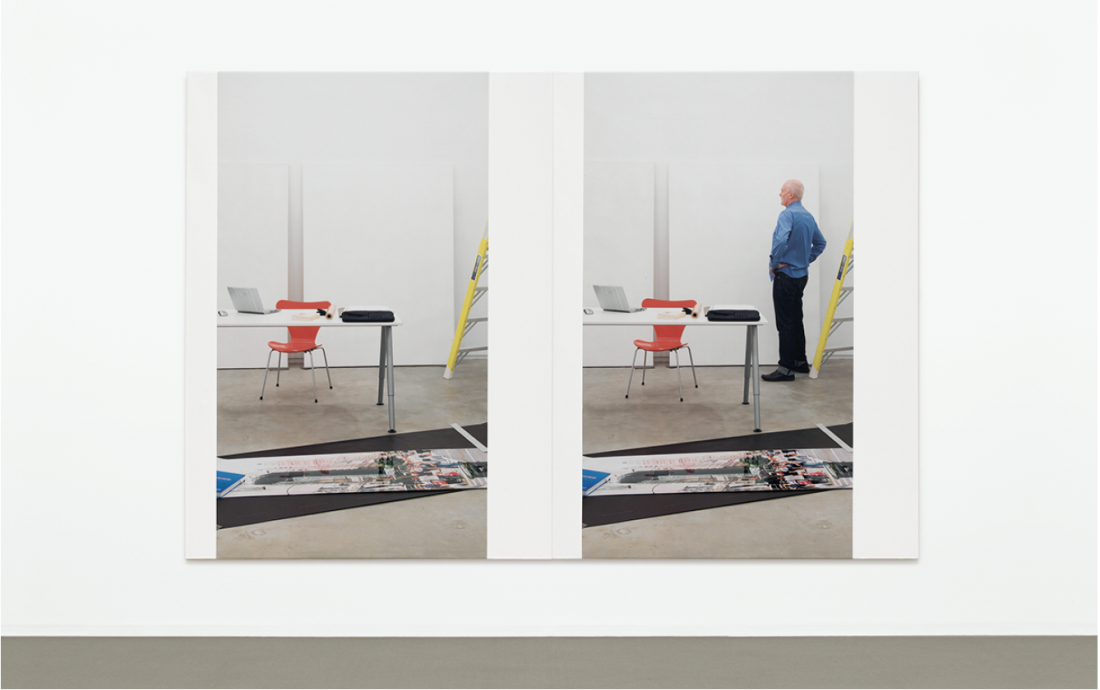

Ian Wallace, At Work 2008, 2008 (detail), photolaminate, acrylic on canvas, 4 diptychs, 203.5 x 305 cm each. Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, purchased with funds from the Jean MacMillan Southam Major Art Purchase Fund. Photograph: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery

The artist-as-researcher designation is commonplace in academia today, but it wasn’t always so. Inside and outside academia in the not so distant past, with a few exceptions, the incentive and motivation for artists to make a substantive personal investment in the conceptualization of their work in a cultural and historical context was limited. The artist produced the work, the art historian, theorist and critic determined its meaning and place in visual culture. It wasn’t until after the Second World War that the intersection of art, visual culture and theory began to take hold and define individual art practices—how artists produced, articulated and contextualized their own work. While specialists in the fields of philosophy, art history and critical theory continue to engage in research and academic scholarship, for most working artists today there is little distinction to be made between creative and critical practice. This evolving pattern, symptomatic of a wider turn to criticality, was set in motion decades ago by numerous factors including the collapse of connoisseurship, the erosion of High and Low, the influence of academia and advanced degrees, the growth of the arts and publication industries and, more recently, the internet and knowledge economies, internationali-zation and interdisciplinarity. The measure and type of applied and pure research now undertaken in the field of artistic production and professionalization has transformed not only the framework of art and methodologies of its critique, but the very connotation of the word artist itself.

As much as the word artist proves unstable, a conventional reading of the terms studio, museum and street as sites of arts production, presentation and economy also quickly exposes limitations. Yet these very limits are in part what appear to inform Ian Wallace’s work. It is the dialectic of the malleability and historical entrenchment of concepts like the artist and the museum that, when situated within the ideological project of Modernity, creates the ideal conditions for tensions between stability and its disruption. For example, to see Wallace as a post-studio artist, as defined by the Or Gallery performance or the “Hotel” series, is only half-accurate as, in having described these very locations as “studios” he reveals his attachment to the traditional idea of the artist’s studio. The adaptability and conceptual possibilities located within the temporal constraints of alternate sites of production are questioned. In a recent four-diptych cycle titled In the Studio 2008, Wallace, situating himself in his own studio, staged a photographic recreation of “At Work.” The model of work in this self-reflexive, mise en scène includes upgraded technology, increased scale (arts economy) and an explicit reference to monochrome painting and the photographic image, a signature of Wallace’s current practice and signifier of his conceptual art origins and the traditional dialectics of modernist art.

Ian Wallace, Lookout, 1979, 12 hand-coloured silver gelatin prints, 91.5 x 122 cm each, 91.5 cm x 1464 cm overall. Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver Art Gallery Acquisition Fund. Photograph: Tomas Svab, Vancouver Art Gallery

Conceptual art proved to be the game changer in late-Modernism and Ian Wallace, as a participant in that experiment, set out by examining Formalism’s boundaries and painting’s limits in the vertical monochromes, 1967, the Plank Pieces, 1968, and the “White Line” works, 1969, some of which were recreated and shown at the VAG. These works were all minimalist by description and oriented to self-referential material and optical meaning in an effort to question the premise of art’s autonomy and the ideals of high modernist Formalism. Wallace’s critique of Formalism’s aspirations revealed that monochrome painting emptied of all external content achieved non-objective abstraction or formal purity, but as we learn in the retrospective and from the artist’s writings, this limitation and strength, while unique to art, was essentially closed to historical, societal and cultural contexts. This absence influenced the artist’s turn to photography, specifically the urban subject and the street.

Later in his monochrome-photography composites these historical antagonists are placed together in their most definitive states (field and image) engaging the parallel discourses that run throughout modernist art history: a Kantian-influenced ideal of art’s autonomy and of Hegelian subjectivity and socialization. Through a conceptually grounded montage, juxtaposition of individually distinct units, concepts of abstraction and representation, and figure and ground, are not only imbricated but ironically united into a new and ambiguous pictorial Formalism. In this achievement, it is also necessary to acknowledge Wallace’s continued inspiration from and reference to literature, to Stéphane Mallarmé in particular, for whom the “blanks” were important when words were dispersed upon the surface of a page. Mallarmé once said something to the effect that his work did not at all break with tradition, he just adjusted it enough to open some eyes. ❚

“Ian Wallace: At the Intersection of Painting and Photography,” was exhibited at the Vancouver Art Gallery from October 27, 2012 to February 24, 2013.

Gary Pearson is an artist and associate professor at UBC Okanagan in Kelowna.