Graham Cracklings: Rodney Graham’s Conceptual Energy

While known as a photo-conceptualist, there didn’t seem to be anything he couldn’t do, and wouldn’t try. His work in sculpture, video, painting, performance, music and song writing was notable for its wit and humour. His description of Vexation Island, the 9 minute-long video which he featured in the Canadian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1997, is characteristically broad ; he called it “a Hollywood version of a Fluxus performance piece”. Graham’s intelligence was everywhere apparent in everything he did.

The following interview was published in Border Crossings, vol. 29, no.1 in February of 2010.

It’s not enough that what artists have to do is invent work; sometimes they have to invent themselves. In 1997, Rodney Graham decided it was time to become a new artist. He had been producing conceptual pieces, like Reading Machine for Parsifal. One Signature, 1992, that were intricate and complicated both in their making and understanding. “I really wanted to be a different kind of artist at that point,” Graham says in the following interview. “I was finding the text-heavy conceptual works I was making less and less satisfying.” The result of his combined dissatisfaction and re-invention was Vexation Island, the nine-minute-long video that he exhibited in the Canadian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1997. He called it “a Hollywood version of a Fluxus performance video,” and he expressed his intention in the language of music technology. This island reverie was “a conscious effort on my part to amp everything up.”

Artist’s Model Posing for “The Old Bugler, Among The Fallen, Battle of Beaune-la-Roland, 1870” in the Studio of An Unknown Military Painter, Paris, 1885, 2009, 181.9 x 247.9 x 17.8 cm, painted aluminum light box with transmounted chromogenic transparency. Courtesy Donald Young Gallery, Chicago, and Gallery Hauser & Wirth, Zurich.

Graham had made an earlier video, Halcion Sleep, 1994, in which he used himself as a performer, but Vexation Island was an entirely different venture. Halcion Sleep was shot in noirish black and white, whereas Vexation Island pushed the spectacle button. It was slapstick Robinson Crusoe, all high-key Caribbean colour and low-grade coconut humour. It made Rodney Graham an art star.

Production still for Artist’s Model Posing for “The Old Bugler, Among The Fallen, Battle of Beaune-la-Roland, 1870” in the Studio of An Unknown Military Painter, Paris, 1885, 2009 Photograph: Scott Livingstone. Courtesy Donald Young Gallery, Chicago, and Gallery Hauser & Wirth, Zurich.

It also confirmed the kind of artist he wanted be. He escaped “the conceptual straitjacket” he had wrapped around himself and, in the process, was able to dress up his art. He also began to dress himself up. The films that followed Vexation Island, including How I Became a Ramblin’ Man, 1999, City Self/Country Self, 2000 and A Reverie Interrupted by the Police, 2003, are costume dramas in which Graham uses different film tropes–the western, the adventure of a country bumpkin going to the city and the convict film–to tell a particular kind of story. Graham considers his narratives “part of a shared popular culture,” and while his employment of film genres didn’t start out being systematic, he did find a way to plug in to the wider culture from which his earlier work had excluded him. He was frustrated when he received critical appreciation without any attendant popular recognition. His foray into simple storytelling changed all that.

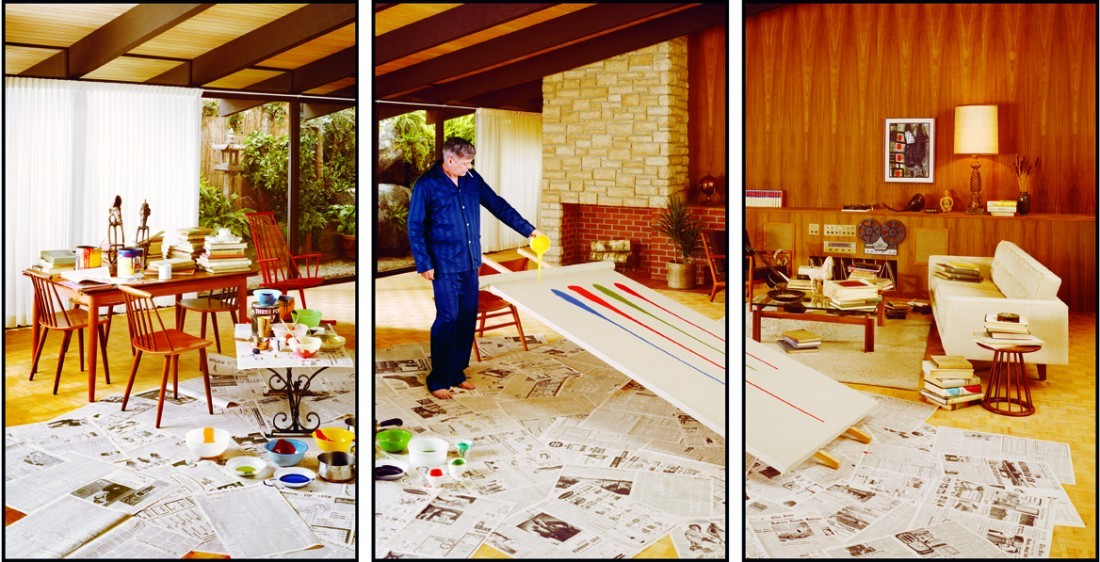

There are occasions when the stories get more complicated. The Gifted Amateur, Nov. 10th, 1962, 2007, (three painted aluminum lightboxes with transmounted chromogenic transparencies) shows a would-be painter making art in his West Coast modernist pad, part Hugh Hefner, part Morris Louis. Graham invents a backstory for his bohemian wannabe, centering “around a hypothetical guy having a late, mid-life crisis,” and the image flows from there. Nor is the story of a man coming late to painting without a certain amount of applied autobiography; for a number of years Graham has been making small works (mostly untitled, in either oil on paper and linen or crayon and liquitiex on paper) that reference the tradition of twentieth-century painting. Graham negotiates a fine line in these casually serious works; he is both paying tribute to and having fun with the vocabularies and mark making of Modernism.

Vexation Island, 1997, film still, 35mm colour film transfer to DVD, 9 minutes, shown on continuous loop. Courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery, London.

Vexation Island, 1997, film still, 35mm colour film transfer to DVD, 9 minutes, shown on continuous loop. Courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery, London.

In the same way, Torqued Chandelier Release, 2005, his five-minute-long 35 mm film, gets to occupy both sides of the aesthetic playground. As a film showing a glass chandelier rotating sideways in space, it is a record of pure, mesmerizing beauty; as a wink-and-a-nod in the direction of Richard Serra’s massive torquing of a very different material, it is pure mischief. Graham says his chandelier piece addresses “high seriousness in a slightly ironic way.” But it’s often the case that when he uses quotation, or works in the manner of, the results end up being more about homage than hijinks.

In this regard, he doesn’t shy away from the manifest seductions of elegance and beauty. His video called Rhinemetall/Victoria-8, 2003, which shows the dusting of a mint-condition 1930s German typewriter, is a gorgeous elegy. Watching the slow enveloping process evokes a feeling of poignant melancholy we normally don’t attach to objects. It is as exquisitely beautiful as the Allegory of Folly: Study for an Equestrian Monument in the Form of a Wind Vane, 2005, is exquisitely ridiculous. The study is a black and white diptych set in a pair of light boxes in which Graham mimics the pose of the great Renaissance philosopher Erasmus in the 1523 masterpiece by Hans Holbein the Younger. The difference is that in the re-staging, he is sitting backwards on the horse. In Graham’s art, dignity and truth, along with beauty and humour, are in a constant state of being reconfigured. He reminds us that the act of making art is a layered engagement with how we see ourselves, how we have seen ourselves, and how we will see ourselves in the future. Whether he wants it that way or not, Rodney Graham ends up being the embodiment of the gifted professional.

BORDER CROSSINGS: It looks on paper as if your university career wasn’t what you would call distinguished. When you went to the University of British Columbia had you intended to become an artist?

RODNEY GRAHAM: I didn’t really know. I was one of those people who wanted to do something in the creative area. I was thinking of writing and I was interested in English. It was Ian Wallace’s survey class where I resolved to be an artist. I wasn’t aware that Vancouver was special at the time and I didn’t know anywhere else. There were visiting artists and there was Alvin Balkind’s gallery at ubc. I came in a bit after the peak in the ’60s, but it was an exciting time and I learned a lot. Jeff had been away and then he came back in the early ’70s. I had read his thesis on Berlin Dada and he was kind of legendary. When he came back I collaborated with him and Ian on a film project that didn’t work out, but it led to a lot of other things. Ian ended up with a pretty good piece called The Summer Script, one of the first very large photomurals, and it led indirectly to my 75 Polaroids piece. Jeff’s whole thing with cinema eventually resolved itself into his big static cinematic light-box images. So it was a heady time and for me a kind of apprenticeship because these guys were a few years older and had a lot of experience. They also had a background in painting.

Was music always part of what you were doing? You must have played as a teenager?

Just in that amateur way and then I worked a little bit with Frank Johnson We were a duo making taped experiments, and then when the uj3rk5 thing came along, we were galvanized by the whole punk new wave scene, specifically Devo, the ultimate inspiration for art school bands. So we thought we’ d give it a try. We initially practiced in the sfu downtown studios, and then in the Art School studios downtown because Ian was teaching at the Art School and Jeff was at sfu. We managed to sneak in at night and rehearse. It was a pretty amazing band and a good time for music in Vancouver. Even though we were already ten years older than all the kids who were doing that kind of music at the time, it was great to be part of the scene. We were in something of an oddball situation, but we got gigs and had a following and it was good for a few years. Jeff and Frank would write all the lyrics and we worked the music up as a group. It was original material.

Flanders Trees, Oak, Kagevinne, 1989/2001, transmounted monochromatic c-print, 180 x 230 cm. Courtesy the artist.

The band developed an underground reputation. Did it just run its course?

Bands don’t generally last that long anyway. There were members of the band—like Frank and me—who were interested in pursuing it further, but Jeff and Ian had regular jobs. We had a kind of half-hearted label offer. The record companies were picking up anything that looked like it might stick to the wall. The record was originally released on a local Indie label, Quintessence, and then it was picked up by PolyGram. It looked like something might happen but it never did.

You get your first one-man show in 1979. Was that a quick start?

No. To tell you the truth I didn’t have a lot going until 1985, which is when I really started showing. I had the opportunity to show in Germany at the Rüdiger Schöttle Gallery in Munich and then in the Skulptur Projekte in Munster in 1987. My career moved forward more in Europe than here. Then things started to happen. I had a Canada Council grant that enabled me to make a couple of major pieces, including the Two Generators film in 1982–83.

Flanders Trees, Linden, Hundelgem, 1989/2001, transmounted monochromatic c-print, 180 x 230 cm. Courtesy the artist.

The story goes that when you showed Vexation Island in Venice it was a definite turning point for your international recognition. Is that the way you see it now?

Completely. It was a conscious effort on my part to amp everything up. I had been doing conceptual work, sometimes obscure, and I wanted to do something more accessible. I was really conscious about making a crowd-pleasing work. I wanted to make work that was less conceptual, that engaged the idea of spectacle more. I knew that Venice was an opportunity, and I put all my money and effort into making the work effective. It was nice that it worked out the way it did, but it was planned, it didn’t just happen. That work came out of an earlier piece called Halcion Sleep, which was my first video and the first work in which I used myself as a performer. It emboldened me to continue. Vexation Island deals with a similar theme in a way, in which I also use myself, but I amped up the spectacle component by making a mini-Hollywood film. I also wanted to exploit the rustic-hut characteristics of the Canada Pavilion. When I first encountered it in Venice, it was boarded up and looked quite different from the pavilions on either side, Germany and its fascist architecture and the neo-classical style of the British Pavilion. I really wanted to be a different kind of artist at that point. I was finding the text-heavy conceptual works I was making less and less satisfying. I wanted to do something that didn’t involve so much information and so much backstory. I wanted something that spoke more to a collective visual memory.

It was a radical shift wasn’t it? Vexation Island had such high production values combined with what is almost slapstick. Was that a conscious orchestration?

My dealer at the Lisson Gallery said you should take advantage of the opportunity and do something spectacular. You could say it was cynical and calculating, but I was thinking about the nature of a venue in which you can only engage a viewer’s attention for a certain amount of time. I was fed up with making works that received critical appreciation but didn’t have any popular recognition. Plus I had this idea that I thought was strong and would work in the context of the pavilion. It was something of a last ditch gamble because I put everything I had into it.

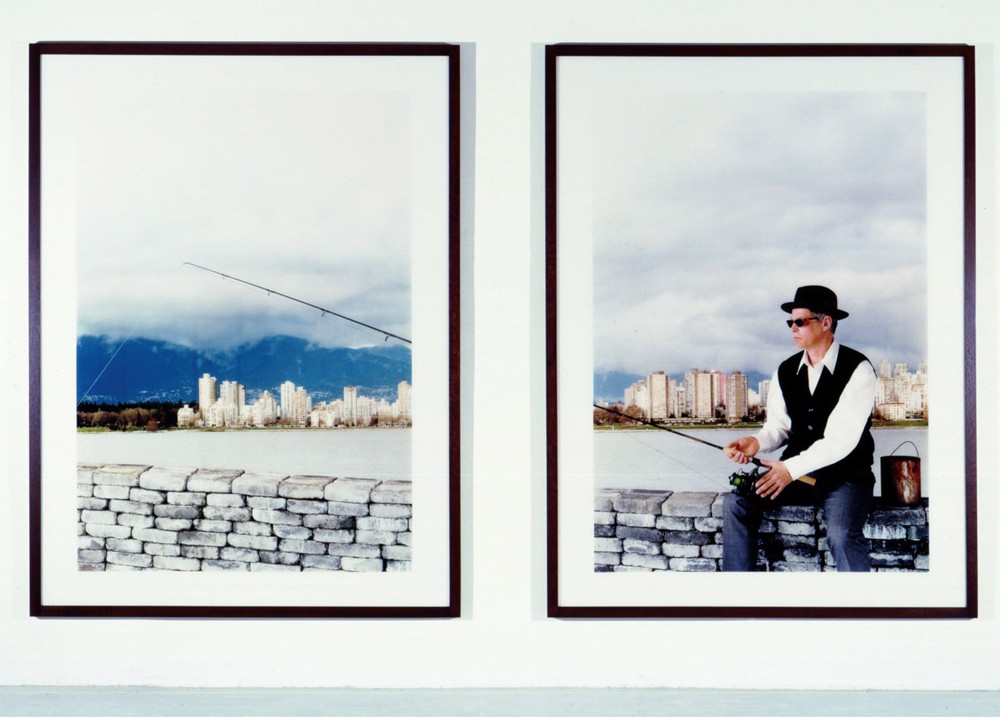

Fishing on a Jetty, 2000, diptych, transmounted chromogenic print, wooden frame 243 x 396 cm, installed dimensions. Courtesy the artist.

A lot of your work has dealt with your being asleep, unconscious or in the process of altering your state of consciousness. Were you aware there was a connection between Halcion Sleep and what you did in Vexation Island?

Yeah. I really thought of it at the time as a Hollywood version of a Fluxus performance video. I wanted to re-do it so it looked like a spectacular remake.

It’s Robinson Crusoe isn’t it? Looking at it, you can’t help but think of an adventure tale.

Totally. I was thinking quite specifically of the scene in Robinson Crusoe where he wakes up after he has tried to circumnavigate the island and his parrot is speaking to him. I had been thinking about the image of a castaway for a while, and it came together with the slapstick gag of the coconut tree as a recurring loop and a narrative device.

Halcion Sleep has a film noir quality. In How I Became a Ramblin’ Man, you do the western; you do a convict tale in A Reverie Interrupted by the Police. Were you conscious of systematically working certain cinematic genres and tropes?

When I did Halcion Sleep, I was thinking of the film noir convention, and of the kind of scene where someone is drugged and taken to the outskirts of town. So it was a conscious inversion of that trope in which I created a benign context for the convention of drugging and kidnapping. But I hadn’t planned at the time to work through film styles systematically. Then the reception of Vexation Island started me thinking that I should pursue this. The western was a way of integrating my interest in music. It was one of the few times I’ve incorporated my music into an artwork. I thought of it as the musical interlude in the Gene Autry and Roy Rogers films of the ’30s, which had always interested me. They were kind of proto-music videos. I thought I would explore that and so I wrote the song for the western piece. The other one in the trilogy,_ City Self/Country Self_, was inspired by a booklet I found in Paris illustrating the adventures of a country bumpkin who comes to Paris to collect an inheritance from a relative. He is subsequently abused by all the city types. That awoke something in me.

City Self/Country Self, 2000, 35 mm film transferred to DVD. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

City Self/Country Self plays the sophisticate against the bumpkin, and the lyrics in How I Became a Ramblin’ Man tell us that “city life just got him down.” He also leaves the city for the country. Was that a reflection of your own experience as the son of a logger who had spent lots of time in nature?

It’s something that had been in my work since pieces like Lenz and the Two Generators film, Illuminated Ravine and Camera Obscura. I guess they were a little bit about British Columbia, too, in that I was partly responding to the landscape.

Dan Graham told us that when he first saw your Illuminated Ravine in 1979 he thought it was better than Michael Heizer.

That’s nice of him to say. Dan was so important for Vancouver and having feedback from him was super encouraging. Jeff and Ian used to bring him out to lecture when they were teaching and he had a real impact on the scene in Vancouver.

When I looked at your maquette-sized Millennial Project for an Urban Plaza, it reminded me of Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International crossed with Dan Graham’s rooftop piece at dia in New York.

I was thinking when I made it I wanted to evoke some kind of 19th-century utopian idea of architecture, something a little bit Nemo-ish from Jules Verne. I’ve never thought about it, but you’re right about the Tatlin Monument.

It’s commonplace in the music industry that if you’ve had a hit album the critical thing is to have a quick follow-up. What interests me about your career is that you had done so much good work prior to Vexation Island—I’m talking about the Camera Obscura work, the outdoor light projections—that it’s as if your second album already existed in your earlier work.

That work doesn’t speak to me so much but it had its place. At the time, I tried to reinvent myself. There were a lot of people who were really ramping it up in an intense way, like Jeff Koons, and I was looking at that work with a little bit of envy. I don’t always like it, but you had to admire its crazy level of ambition. There was something about it that got me thinking about finding a way to move out of the conceptual straitjacket I had put myself in. I was sick of doing work that involved a lot of research into some obscure historical fact, like the Reading Machine for Parsifal. It was successful, but I was tired of explaining it. There was such an apparatus attached to it, so much backstory, that I just began to envy people who worked with a different relationship to verbal or textual exegesis—like painters who can appreciate something in a more direct, immediate way.

Were you aware of the performance work that Gathie Falk and Tom Graff were doing in Vancouver? There were local precedents for making the shift from a conceptual frame to a performative one.

When I entered the arena, my ideal was a certain kind of rarified conceptual art, and I have to say I turned my nose up at performance at that point. Now I look back on it in the same way that I’m looking at a lot of painting.

When I first saw the Flanders Trees, I thought that you were riffing on Baselitz.

I was thinking more of the upside down trees Smithson did on his Yucatan walk. It also came out of the camera obscura thing because that’s the way the image looks on the ground glass in the back of the field camera.

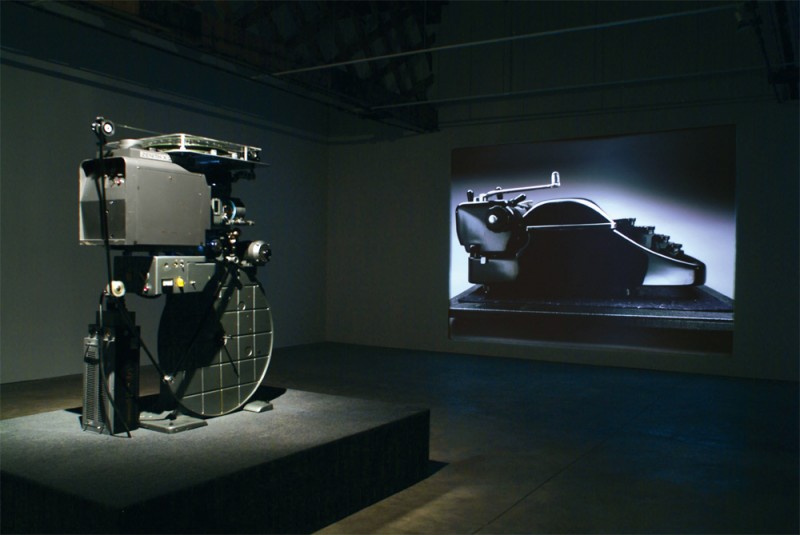

Rheinmetall/Victoria 8, 2003, 35 mm colour film, no sound, 10:50 minutes, projected on continuous loop, Cinemeccanica Victoria 8 projector and looper. Courtesy Donald Young Gallery, Chicago.

So the technology directed the way the image would look as much as any notion you had of upsetting the way we perceived the world?

Yeah. I was simply interested in what the technology of the camera obscura did. Those pieces were extrapolating from an earlier piece, which was really about placing a building in a certain relation to an isolated tree. I was thinking of this ideal of functional architecture.

It isn’t just the antiquated subject matter that makes the Rome Ruins from 1978 look historic and archaic, it is also the way they look. It’s as if you tramped back through time to make pictorialist photographs. What were you thinking about when you did this series of pinhole photographs?

They were taken with a camera that I made in my hotel room just after my regular camera was stolen. I remembered this little Kodak booklet that I had bought years ago describing how to make a pinhole camera for 110 film that you would wind through with a nickel. I knew that the subject matter of the Roman Forum would lend itself a pictorialist treatment and that the softness would be a natural function of the pinhole lens.

When you did Halcion Sleep you must have been aware of Warhol’s Sleep from 1963?

I was aware of it but I wasn’t consciously trying to evoke it.

Were you asleep and unaware of what was going on around you?

Yes. Partly through sleep deprivation and because I took a double dose of Halcion. I would occasionally wake up, but I could put myself back to sleep pretty easily. I planned the shot so that it would have the effect of making the rear window look like a thought balloon, and I was also aware that as I approached the centre of the city, the lights would become more intense than they had been in the suburbs. So a narrative would be told by the lights. It was also slightly rainy, so the windshield wipers added a quality. That piece was the one that changed things a lot for me and made Vexation Island possible. I was interested in this idea of degree zero performance by virtue of just being there in the subconscious.

Typewriter with Flour, 2003, chromogenic transparency, Plexiglas, steel surround with Hammerite finish, 40.6 x 49.5 x 10.1 cm. Courtesy Donald Young Gallery, Chicago.

Do you like dressing up? As the film work progresses you seem to get better and better as a performer/actor. Is that something you were actually aiming for?

I feel I’m actually stiff as a performer, but then I don’t put very big demands on myself. I like to telegraph a lot through the costume.

I just did a new light-box piece called Artist’s Model Posing for “The Old Bugler, Among The Fallen, Battle of Beaune-la-Roland 1870,” in the Studio of An Unknown Military Painter, Paris, 1885. I’m wearing a French garde mobile uniform from the Franco-Prussian War era, and I’m just lying on the floor of a 19th-century studio posing for an artist you don’t see because he’s out of the frame. Originally, I was going to include the artist, but it became too big. I’m always interested in doing something where I get to wear a costume. It’s amusing.

So these literally are costume dramas for you? You do it in Dance!!!!!, too, where you’re the city slicker who’s forced to do the bullet dance by a gunslinger on the other side of the saloon?

Yes. I wanted to be an urban type who was obviously from out of town. It’s the revenge of the character in City Self/Country Self. I discovered in doing the piece that the image of someone being terrorized by a gun-wielding yokel in a bar is as old as cinema itself, even older. I think there’s a scene in The Great Train Robbery where people are forced to dance by robbers. I was thinking of Abu Ghraib as well, and what should be considered funny. You laugh when you see it in a movie, but you don’t laugh when you see those photographs. So I was interested in the play between humour and hard reality. I wanted to evoke that uncomfortable feeling you get when you laugh at someone being victimized.

One of the things that struck me in looking at Ramblin’ Man is how much sound takes precedence over image. It has a very intense sound bed from the rub of the body on the leather saddle to the splash of the water, to the sound of the horse hooves on the rocks. Were you deliberately privileging sound over image?

That piece had a lot more foley work than we had ever used before. The most interesting part was doing the foley work for the horse because we repeatedly forced a gumboot on the end of a stick into the water. Then we looped it and created these rhythmic patterns. It’s amazing how your head synchronizes the eye and the ear. It was pretty loosely done, but we spent a lot of time on it because the sound is important.

Allegory of Folly: Study for an Equestrian Monument in the form of a Wind Vane, 2005, diptych, black-and-white transparency, Plexiglas, aluminum, installed dimensions: 306.3 x 290.1 x 18 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Were these scenes storyboarded?

None of them were._ City Self_ was storyboarded by somebody else but based on my description of what I wanted. In Ramblin’ Man and Vexation Island, so much was hinging on common Hollywood conventions that I knew everybody shared. With Ramblin’ Man we didn’t even really have a director, we just all talked about it. There was a Director of Photography, of course, but we started in the morning and the plan was that I would ride in, sing a song and ride out. We could only afford to shoot for one day so it was a question of getting as many shots as possible. We started at sunrise and the last shot of the film ended at sunset. We did scout the day before but it was location driven, the same way that Vexation Island was. Once you find a location, the action is so minimal that it almost directs itself.

When did you decide that the loop was such a useful structural device? The larger question is, does the loop have a philosophical dimension that goes beyond its narrative advantage? Do you think life is a series of repetitions in which we’re caught in some sort of psychic Myth of Sisyphus?

Certainly the loop is useful in the sense that it acknowledges the way films are seen in a gallery and museum context. That’s the first thing. The second thing is that it is interesting to work with as a structural problem. Where do you place the loop, how do you facilitate the transition from the end to the beginning? I don’t really think about the larger philosophical thing too much, although in Vexation Island there is a Sisyphean implication. In the other ones it is more of a structural thing. Ironically, the first loop piece I did was a text piece, but it functions in a different way. It doesn’t go back to the beginning but back to a middle point in the narrative. That was the first piece I did in which the loop could also have metaphysical implications.

You use that mis en abyme idea in Paradoxical Western Scene, where the wanted cowboy is endlessly repeated. That strikes me as the static equivalent of the kinetic loop, in that it comes back forever.

Yeah. In that one I was interested in doing the mis en abyme thing in the most stupid, really dumb-ass way possible.

It is kind of dumb ass, but you look good as a cowboy.

I felt pretty good about my costume. I tried to slim down for that one.

Was it the repetitive explosions at the end of Zabriskie Point that you found so appealing? It’s the sex scene that usually gets more attention than the exploding buildings.

I did a piece with the sex scene in the desert. I had always been interested in the use of music in that film, which is amazing. Jerry Garcia played the music, but a lot of groups were involved. I think Pink Floyd did the scene at the end, and Kaleidoscope was also involved in the project. Antonioni had a lot of money, and he hired a number of musicians to make proposals specifically for that desert scene.

You base Rotary Psycho-Opticon on a Black Sabbath appearance on Belgian tv in the ’70s. What is your reason for invoking the ghosts of music past in your work?

That was fortuitous. I saw that apparatus on a video compilation that somebody had made. I think the set might have been used for every band that played there, so it may not have been made specifically for Black Sabbath. It was for this show called Top Pop and I guess it was typical of the cheesy backdrops used for bands on shows back then. But it struck me as a particularly interesting one and I liked its simple mechanical character. So I designed the piece as a backdrop for my own band that would exist after the performance we did in New York. We also did it in Glasgow. I made a smaller version of that piece, too, a more domestic-scaled one. In the original television show there was probably a stagehand manually turning the giant wheel, but I speculated it might have been hooked up to a bicycle. So I made the smaller one that you could ride like an exercise bike and then look at the pattern in front of you.

The bicycle is beautifully made. The saddle looks like it’s such fine leather.

It is a really good one. I had them made by Toby’s Cycle Works in Vancouver. He’s a bicycle builder and a genius.

I’m interested in the way you use objects of technology. I’m thinking of A Reverie Interrupted by the Police when you focus on the innards of the piano. It’s almost as if there’s a Charles Sheeler Precisionist thing going on. It comes up again in the typewriter in_ Rheinmetall/Victoria 8_. What is this fascination you have with elegant functionality?

I was thinking of Cage as well with that piece. I hadn’t thought about it, but the machine aesthetic in A Reverie does relate to Rheinmetall.

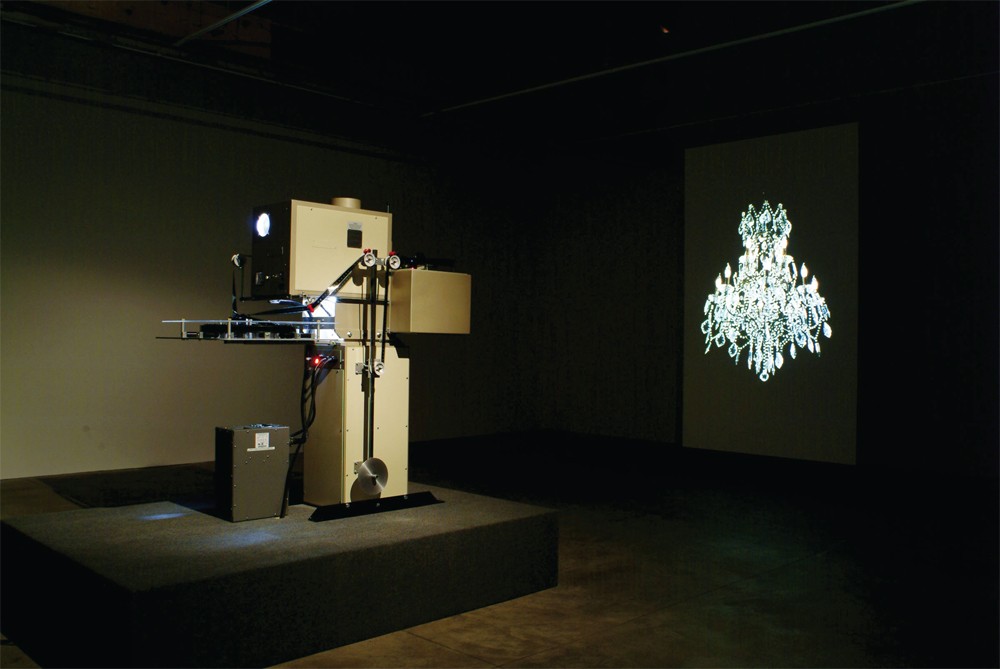

Torqued Chandelier Release, 2005, 35 mm colour film, no sound, 5 minutes, projected on continuous loop at 48 frames per second, custom manufactured vertical image high-speed projector and looper. Courtesy Donald Young Gallery, Chicago.

When you shift the angle on the typewriter it shows itself to be an utterly entrancing object to look at it.

The piece was all about that object. I found the typewriter in a junk store in Vancouver. What triggered the piece was that it was unused. I had had it for quite a while and I wanted to do something with it. I thought I should make a silent documentary that speaks for itself, and I thought of making it in the style of a really slick car commercial and then I pulled back a bit. I was going to have more travelling shots and make it look sexy, like when the camera swoops in on the upholstery of the car. I didn’t realize until later that Rheinmetall was a big German arms dealer, so it has that implication as well. It was interesting that it made its way over to Vancouver from Germany in the 1930s and had never been used. The ribbon was completely intact; there wasn’t a single indentation on it.

The Victoria 8 is also a fine piece of technology. You talk about these two pieces of obsolete technology as “facing off.”

It was probably a formal problem in that I wanted to do a 35 projection without hiding the apparatus. I wanted this really simple aesthetic of having it be visible. It occurred to me that the clattering sound you associate with the typewriter, even if you see it silently, is going to be filled in by the sound of the projector. So it wouldn’t be distracting to hear the noise. It seemed appropriate that the projector be out there, front and centre, on a plinth.

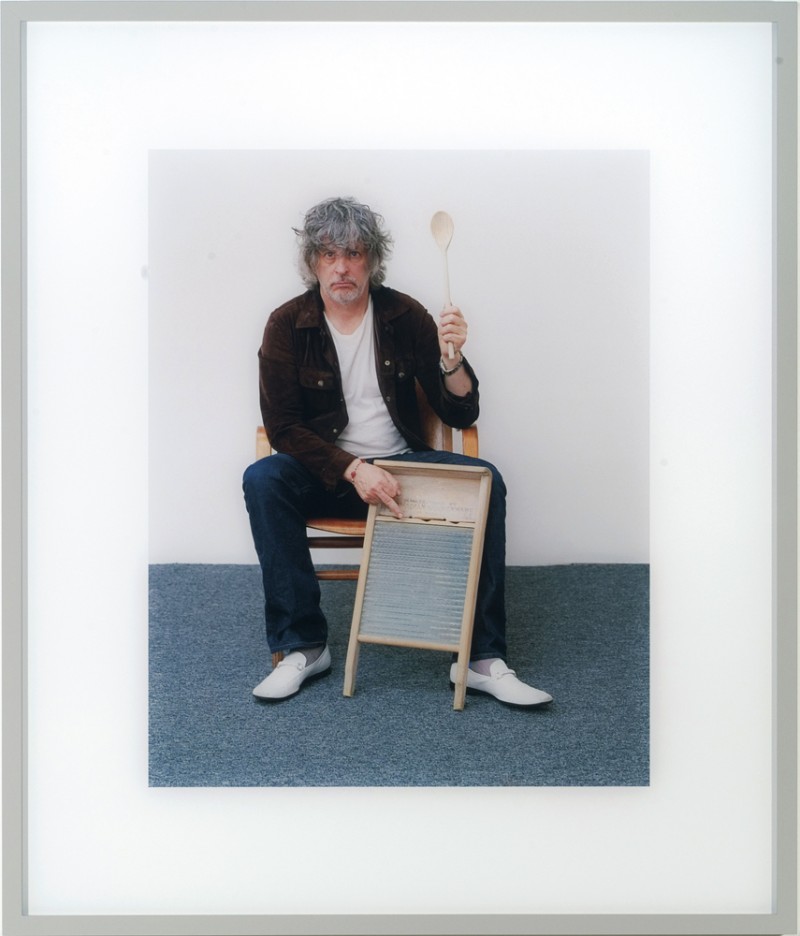

Artist in His Studio, 2006, transmounted chromogenic photograph, framed, 90.2 x 76.9 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Did you intend to invoke a feeling of elegy with the typewriter? The object carries a sense of melancholy.

That was something I was going for. This idea of having flour on it occurred to me spontaneously. I was thinking of a William Wegman piece called Dusted where one of the dogs is covered in flour. But recently I saw Dreyer’s Vampyr, and at the very end, the vampire is in a place like a lime factory, and he gets covered in lime when he is in a cage. I had seen it years ago and it may have been in the back of my mind.

What about_ Torqued Chandelier Release_? It’s like an upscale Flash Gordon spaceship.

That was a bit of a technical challenge since we had to have the projectors made. It took a year because they had to project on their side. I wanted to have the 35 mm film in a vertical instead of a horizontal format so I could train the chandelier in an appropriate way. You know, an oblong vertical chandelier. Also, it’s a special projector that plays at 48 frames a second. I wanted to create this deliriously precise experience, which I think you get because you’re seeing twice as much as you normally see in a film. It’s this almost accelerated stop action where you get a sense of every crystal. When I get an idea like that I really rejoice because I love doing single-roll films. They are so easy and their conceptual elegance is something I really appreciate. It was the upscale version of Coruscating Cinnamon Granules, which was a rather modest 16 mm film.

Maybe you’re a baroque conceptualist. I thought the cinnamon piece looked like a kinetic version of Vija Celmins, in that the burner becomes almost cosmological.

Yeah. When I showed the piece in London, somebody who had had a near death experience told me that it looked like the tunnel people supposedly pass through. I completely wanted that effect, and I hoped I would get it by shooting in black and white. If I were shooting in colour you would recognize right away that you were looking at an element, but in black and white you can’t really tell. You’re looking at a spiral that comes into being as the element heats up. In colour the illusion would have been broken, and I think the cosmological implication of the image depends on that illusion. Also it is the sequel to the Two Generators piece, which is about turning lights on and off, because turning lights on, one at a time, provides the narrative structure of the piece. I was interested in those really simple pretexts for a film. I guess I was influenced by the whole idea of structural film in the ’70s.

You seem to have been able to retain a number of your early interests, which you nuance and finesse. So the conceptual framework from your early work stays but you make it elegant and decorative; now you talk about how structuralist film turns up in different ways. Have you unconsciously preserved a through-line in the way your work has developed?

I hope so. Earlier on, you’re more conscious of that, but at a certain point you have to stop caring about it. I occasionally take missteps and go on side trips. But I’m hoping there is a unity in the end. I worry about it because there is a lot of freedom in the art world to do whatever you want. You have to be aware of that and not just try anything. So it’s good to exert a certain discipline on your work.

So when you do Torqued Chandelier Release, 2005, I can’t help but think of Richard Serra’s sculptures, which torque different material in a different scale.

I was thinking of it as evoking high seriousness in a slightly ironic way. It also just describes the consequences of torquing something and releasing it. I wanted to keep that conceptual simplicity. I like a title to be descriptive in a preliminary but adequate way. I was thinking specifically of Serra, where the irony emerges from the completely different materials that are being used.

Your mention of irony draws me to the works on paper that you have done in crayon. I consider them both satire and homage. They look like they’re acknowledging Albert Oehlen, or Julian Schnabel or Willem de Kooning. Are those works tributes, or are they meant to take the mickey out of that tradition of painterliness?

They’re tributes, but they’re not good enough to be true pastiche. True pastiche involves virtuosity, and to do it well you have to master those things. I’m trying to slowly develop mastery. It’s also not specific homage because I’m not trying to look like anybody. The gestures are small. They don’t get any bigger than 2 by 3 feet, so they’re like easel paintings, more in a European tradition rather than an American one. I don’t like big gestures. I think I’m coming to the end of the cycle because I’m finishing some canvases that I started in 2006. I’ve been working on them for three or four years and the impasto is getting pretty thick.

These are worked canvases as opposed to dripped or poured canvases in the Morris Louis tradition then?

Yes. My level of literacy in terms of painting is not that high because I skipped the painting phase. I was thinking about that recently because people like Ian and Jeff were painters before, and they engaged this sort of struggle when they consciously moved into photography after moving away from painting.

And you avoided that entirely?

I never really got up to speed. I painted a little bit in high school but I didn’t go to art school. I was at university so I missed that phase, and I’m entering it at a late period of my life, so it’s hard to talk about it. It’s not like I know that history, I’m just learning it now.

Painting is supposed to be compromised and you come to it like an innocent.

A little bit, I guess. I certainly don’t have any guilt feelings about it. We’ll see. I want to continue working with paint in some way, but it’s a little messy and undisciplined.

Why do you pick Morris Louis in The Gifted Amateur, and why does a specific date, November 10, 1962, come up in the title?

We just chose a date that was after the opening of the last Morris Louis show. The backstory I concocted for myself is that this character is a professional of some sort who didn’t know very much about art. Maybe he had seen the last show where Louis exhibited the drips. He is so inspired that he thinks he might try it himself in his living room. I was inspired by the fact that Louis made those large paintings in his Baltimore kitchen alcove, an area that was much smaller than the paintings themselves. The space was 9 by 12 feet and he worked in from each side, rolling them up and working on less than half the canvas. So the anecdotal thing of Louis working at home initiated my interest, and that was increased by his way of painting. He didn’t make studies; he would just drip all day long. His wife would go to work and he would start doing these things. He made hundreds in a very short period of time before he died, and most of them weren’t even stretched. Originally the piece was going to be a fictionalized account of Louis painting in his living room and what might have happened during the day—the postman coming, making himself a sandwich. But it evolved into this other story centred around this hypothetical guy having a late mid-life crisis. You know, just saying, “Fuck it, I’m getting up in the morning in my pyjamas and I’m going to do it.” I was thinking of Hugh Hefner with the pyjamas and the cool pad with a sound system.

The amateur owns a perfect West Coast modernist house. He may not be gifted but his house is.

We built that set in a school auditorium in North Vancouver. I was thinking of a beautiful house in West Van, like Gordon Smith’s. But we modelled it on a Neutra House. I was thinking of a generic West Coast bachelor pad that looked like a decorator might have put together. It didn’t have much personality, and then the guy just discovered art and decided to buy a bunch of art books. It’s not so unlikely. It has probably happened many times.

The Gifted Amateur, No. 10th, 1962, 2007, 3 painted aluminum light boxes with transmounted chromogenic transparencies, installed dimensions: 285.7 x 558.5 x 17.8 cm. Courtesy the artist and 303 Gallery, New York.

What is interesting about your drips is that they make me think of B C Binning more than they do Morris Louis. That’s your tribute to British Columbia.

It’s true.

Your interest in literature—writers as different as Melville, Poe and Ian Fleming turn up—suggests an attraction to storytelling. That is supported by the fact that you invent this backstory for your character.

I find it a more interesting way of working than the way I used to work. Here the backstory is part of the shared, popular culture and it’s more fun to work with now. In a sense, I guess I am a storyteller.

I was perplexed when I was first saw Schema: Complications of Payment. I didn’t know enough about Freud to understand that what you were doing wasn’t an invention, and I was confused by your performance. I can’t tell if you’re doing it straight or comically; how much is autobiographical, how much is history?

I did a lot of research on one dream, “The Dream of the Botanical Monograph.” I became really obsessed by this thing and almost dropped out of art for a year or two. I did intentionally re-enact some research that had been done, but I also made what I considered to be some discoveries that were possible contributions to the literature. I guess I could have sent it to a psychoanalytic journal, but I didn’t even have the wit to do that. In the end Jeff Wall said, “You’ll get an art work out of it,” and I remember thinking, “I’m not even going to be an artist anymore; I’m going to be a psychoanalyst because this is much more interesting.” I was becoming an expert on that very narrow area of one particular dream. I focused everything on it. I was so fascinated that I filtered my entire reading of Freud through that one dream. There is this mis en abyme structure where he sees this book before him and the book is the book he’s writing, The Interpretation of Dreams. So the dream itself has this kind of Mallarmé elegance about it. I thought it was a key to his work. I made a silk-screened painting as a key to the dream, and the diagram that was the basis of the lecture was my first foray into painting. It was done pretty well straight; I was trying to convey as clearly as possible what I considered to be concrete research.

Academic thinking can get so involved that it becomes hermetic, almost preposterous. There are moments when that seems to be happening. I don’t know whether it’s intentional or whether it just happens when you enter that particular terrain of intellectual inquiry.

I think it’s the latter. I was trying to do it honestly, albeit in an art context. I’m doing this for an art audience. The idea of creating this flow diagram was also a way of explicating a painting. So it was like an art lecture. It could have been a diagram on a blackboard; in this case it was a painting. It was oil on canvas and I was talking about it in the way artists talk about their art. The absurdity was the absurdity of my involvement in this kind of side issue. It really was about being sidetracked. What was funny was the dream was about that, too. The subject of that dream was Freud being criticized for being sidelined by this research. It seemed to have a lot of meaning for me at the time.

It keeps getting more and more inside. I read that you were having financial difficulties at the time and that there was some autobiographical overlap between your predicament and Freud’s.

That’s true. This whole idea of the infinitely deferred debt was operating. That was one of the aspects of the dream I used. That’s the thing about Freud: if you really get into it and cross-reference it, The Interpretation of Dreams is intensely fascinating. Also this dream came at the height of his period of self-analysis, so it works metaphorically on so many levels.

Whilhelm Fliess, Freud’s friend and colleague, criticizes The Interpretation of Dreams by saying there are too many jokes in it, which leads me to ask you about the role humour plays in your work. Is that aspect sometimes not appreciated as much as you’d like it to be?

Sometimes I feel that people think what I do is too in-jokey. Obviously, it’s a defence mechanism against becoming overly serious. But it certainly has been a strategy of mine.

The preceding interview with Robert Enright was conducted by phone from his Vancouver studio on December 11, 2009, as Rodney Graham prepared for his major European exhibition, “Through the Forest,” which opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona on January 30, 2010, and subsequently toured to the Museum für Gegenwartskunst de Basilea in Switzerland, and the Hamburger Kunsthalle in Germany.

To own Border Crossings’ Issue 113 Performance including this interview with Rodney Graham, purchase your copy here