Barry Schwabsky’s PictureLibrary: From Inner Architecture to Unremembered Images

Rhona Bitner, Marianne Mueller, Cristian Ordóñez, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Barry Stone

There are photographers who want to show everything that can be seen. And then there are those who also want to show what can’t. Can you picture sound? Can you picture, even, that sound has been there but no longer? That’s what Rhona Bitner has tried to do with Listen, edited by Éric Reinhardt (Rizzoli, New York, 2022), much more than the coffee-table book it might at first appear to be, which compiles the results of 13 years of the New Yorker’s journeys through the United States in an effort to document what she calls “the inner architecture of American music history.” That phrase, “inner architecture,” is a metaphor, of course—physical structure as vehicle for emotional formation. Bitner’s deep, often sombre colour images of (mostly) interior spaces—bars, concert halls, prisons, recording studios, stadiums, theatres and even the Mississippi crossroads where some people imagine Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil in exchange for his genius on the guitar; or sites where such things used to be: what was the Dew Drop Inn in New Orleans now holds the remains of an abandoned barbershop, while Max’s Kansas City is now someone’s Manhattan loft apartment—make good on what seems to have been her wager, that the seeking eye will find out something of what the ear might once have heard. These sonorous pictures take their place in the long tradition of spirit photography, but more sophisticated than most, they know that spirits are most readily evoked by allowing them to remain intangible. The places she pictures were full, not just of sound but of life, energy, emotion; bodies, sweat, uproar. Their emptiness, sometimes utter abandonment as she pictures them, paradoxically allows the willing viewer to conjure all that. She evokes sound, as Miles Davis would have said, in a silent way.

Am I just reading into Bitner’s images the significance I think I’m taking out of them? Wouldn’t I see them differently, in other words, with different captions, and without Jon Hammer’s detailed “historical notes” on each pictured place (without which I wouldn’t know that Grant’s Lounge in Macon, Georgia, is where Southern rock legends like the Allman Brothers and Lynyrd Skynyrd got their start, or that Miami’s Lyric Theater was a major stop on the “chitlin’ circuit,” where the likes of Count Basie and Billie Holiday used to perform)? Maybe. But I think that that doubt is also part of Bitner’s project. There is a religious dimension to our passion for art, whether that’s music or photography: believing is seeing. Bitner captures the space in which that believing and seeing happen. “You have to play the room” is the musicians’ adage quoted by pianist and composer Jason Moran in his Afterword to Listen—the book also includes writing by Iggy Pop, Greil Marcus and Natalie Bell—and Bitner, never formulaic in her approach to space, does just that.

Rhona Bitner, Listen: The Stages and Studios That Shaped American Music, published by Rizzoli International Publications Inc, 2022.

__Philadelphia__PA__4-1-2008_copy_1080_1080_90.jpg)

Rhona Bitner, Listen: The Stages and Studios That Shaped American Music, published by Rizzoli International Publications Inc, 2022.

Rhona Bitner, Listen: The Stages and Studios That Shaped American Music, published by Rizzoli International Publications Inc, 2022.

Rhona Bitner, Listen: The Stages and Studios That Shaped American Music, published by Rizzoli International Publications Inc, 2022.

A different past resonates through The Book of Complaints and Suggestions: Re-Constructing Constructivist Interiors (Standpunkte, Basel, 2022), with photographs by Marianne Mueller and text by Gabrielle Schaad. Mueller has explained to an interviewer that, working in Yekaterinburg, Russia, on a mission to document constructivist buildings, “while I was still taking pictures and finding access to more buildings to see (and that can take a long time), I went to the stationery store to buy blank notebooks and start stringing the pictures together. Big laugh, because I had bought the famous blank notebook titled ‘Complaint and Suggestion Notebook’ with pre-printed lines for case numbers and handwritten reports.” So both her images and Schaad’s words (in both Russian and English but not the two Swiss collaborators’ everyday German) are overlaid on what you might call the ghost of this only-in-the-Soviet-Union artifact, a compact paperback whose more than 250 pages nonetheless suggest there must have been plenty to complain about.

With few exceptions, the images are printed small, about 2 5/8 × 4 inches—they are meant, I think, to be unprepossessing, to shed the implicit grandeur of state architecture. Most of Mueller’s pictures here, like all of Bitner’s in Listen, are unpeopled; the occasional tiny figure suddenly reminds us that these are small encapsulations–you might even say, miniaturizations—of often vast spaces. Vivid throughout The Book of Complaints and Suggestions is the challenge of adapting buildings constructed for life under state socialism to existence in a market economy; how does a space never meant to contain advertising, for instance, accommodate its presence? Or what becomes of a nine-storey water tower, once a local cynosure, “like a medieval bell tower,” when it is overshadowed by newer high-rises? (Mueller excludes the taller buildings from her frame, lending the tower something of its former importance, yet distanced by the diminutive scale of the image itself, which turns it into a kind of toy, like one of those miniature buildings around model railroad tracks.) Over the last three decades there’s been a lot of European art that has indulged in nostalgia—in Germany they call it Ostalgie—for the monumental architecture of Soviet times and its overweening sense that a heroic reconstruction of the world was not only possible but in progress; also, a lot of easy irony about the ruins of failed utopias. Mueller and Schaad linger on the fringe of those kinds of nostalgia and irony but ultimately dodge them through their unsentimental attention to detail and analytical clarity.

Marianne Mueller, The Book of Complaints and Suggestions: Re- Constructing Constructivist Interiors, 1st edition, published by Standpunkte Books, 2022.

Marianne Mueller, The Book of Complaints and Suggestions: Re- Constructing Constructivist Interiors, 1st edition, published by Standpunkte Books, 2022.

Marianne Mueller, The Book of Complaints and Suggestions: Re- Constructing Constructivist Interiors, 1st edition, published by Standpunkte Books, 2022.

Marianne Mueller, The Book of Complaints and Suggestions: Re- Constructing Constructivist Interiors, 1st edition, published by Standpunkte Books, 2022.

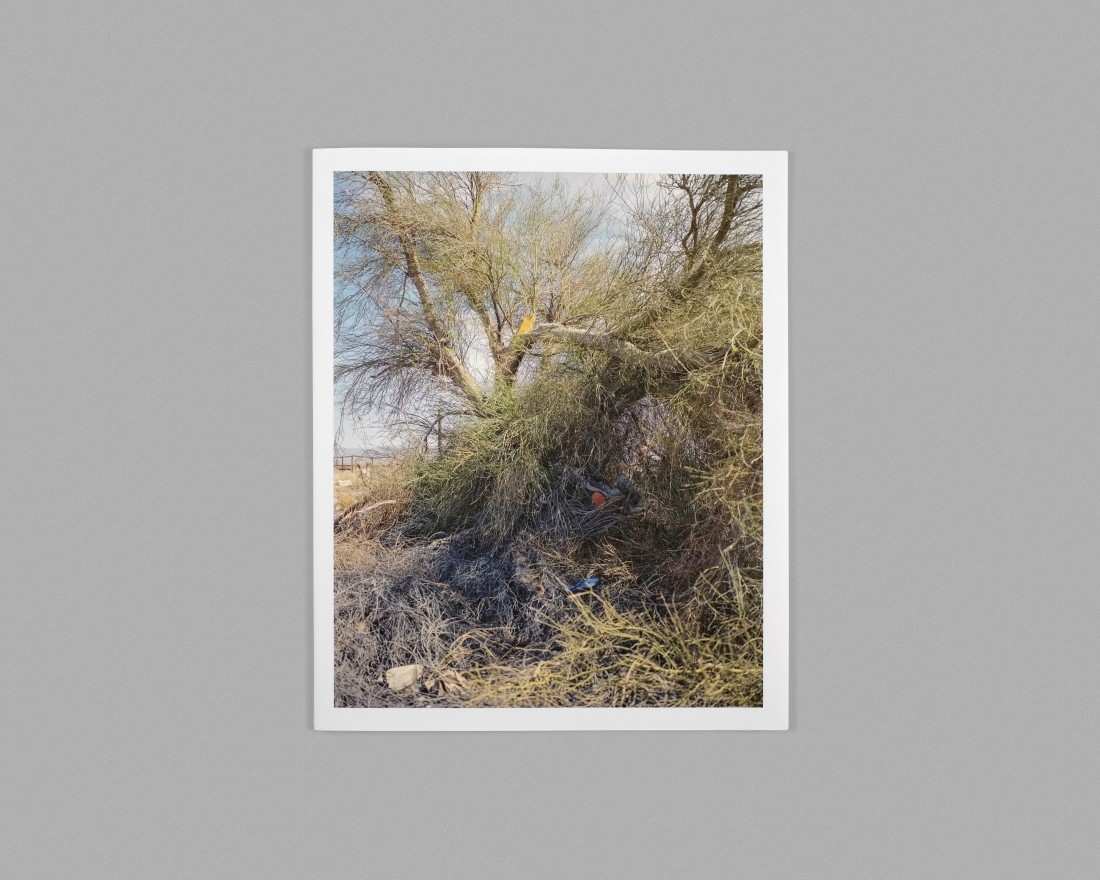

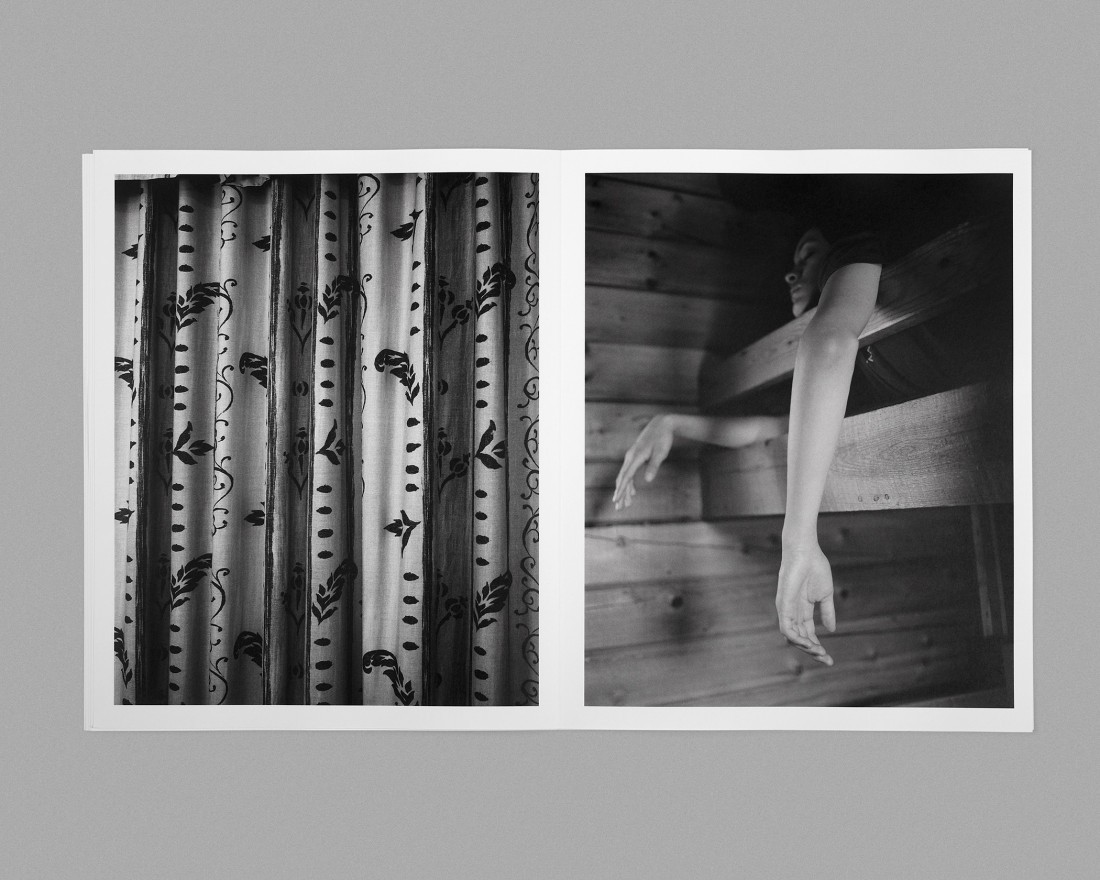

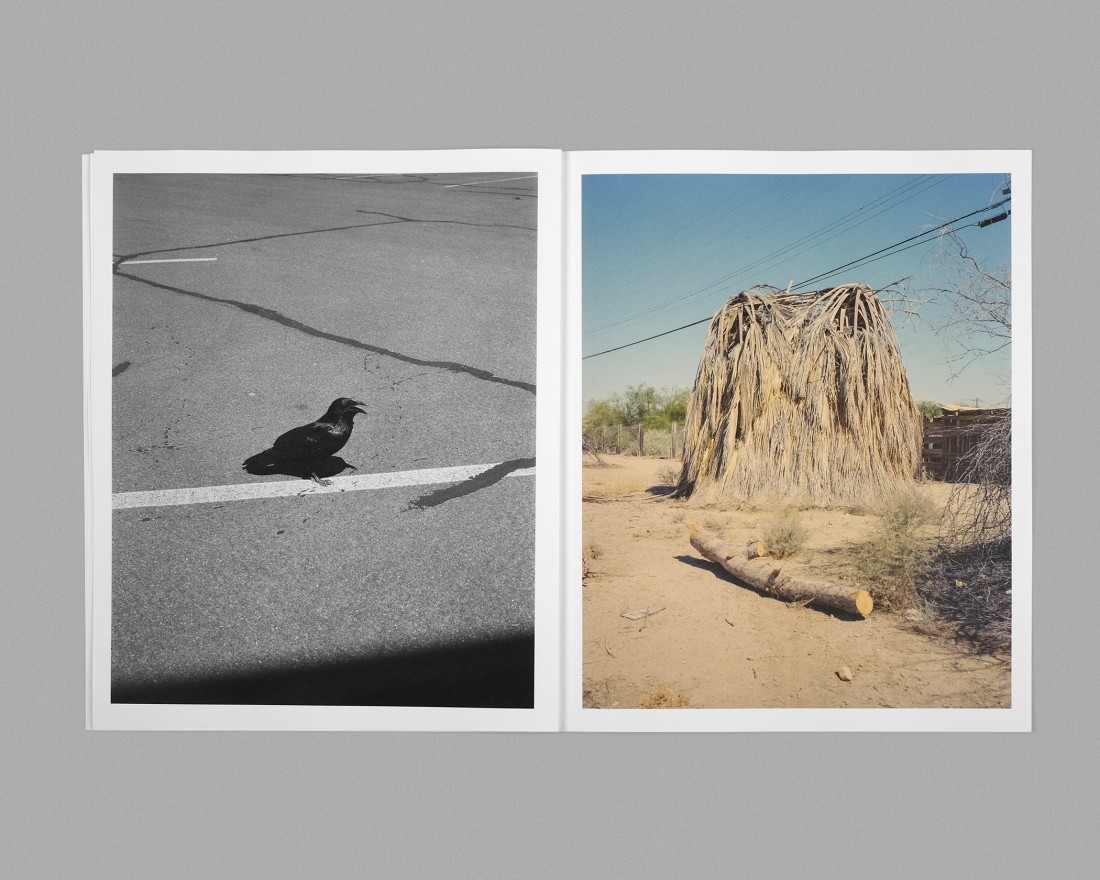

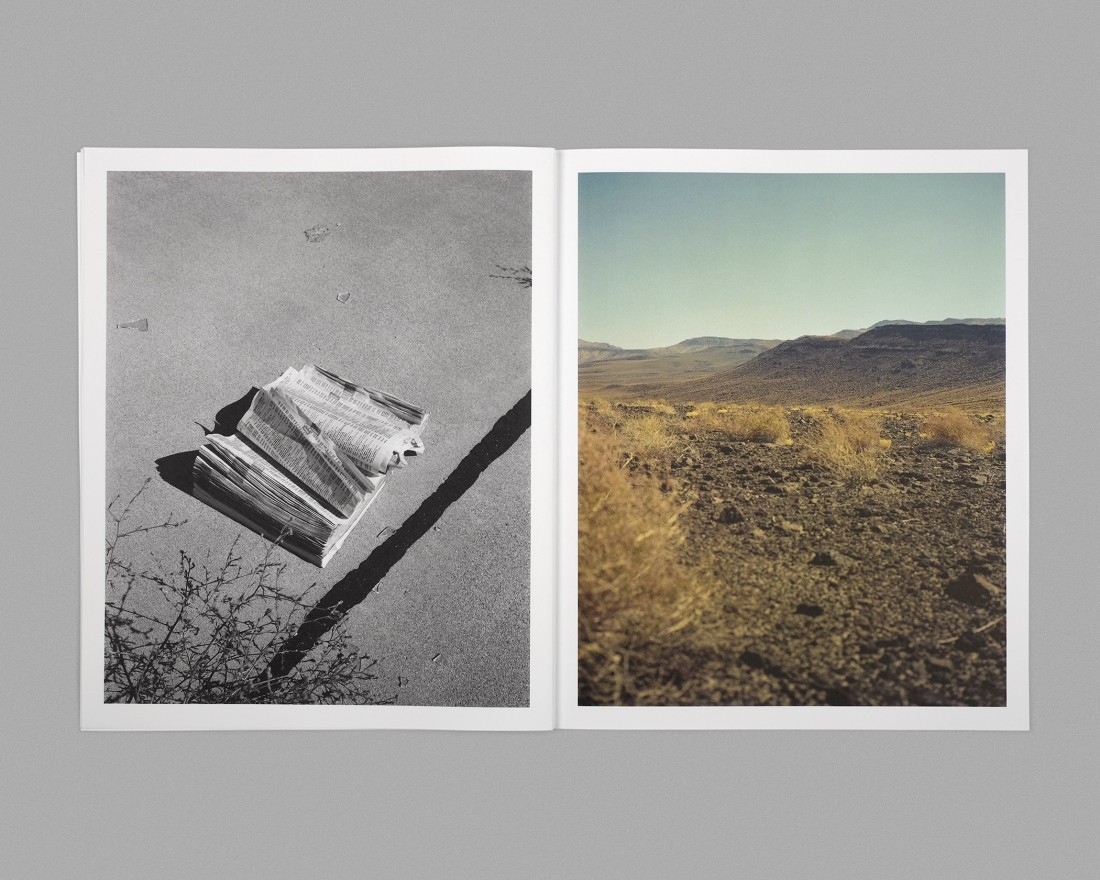

Though it’s nowhere stated in the publication itself, I think I understand from a notice I saw for On Trial by Cristian Ordóñez (acb, Melbourne, 2022; edition of 200) that the 20 monochrome and colour images so crisply reproduced on its seven largish, unbound, folded sheets (the design is by Rohan Hutchinson) are the fruit of a journey the Chilean-born Torontonian took through the United States in 2019. I wouldn’t necessarily have known it from looking at the photographs themselves: Ordóñez is an exquisite observer of place, but his interest in place is not a sociologist’s or even a geographer’s; seeing where you are, in this work, has little to do with knowing where you are. Visiting a country between the one where he started out and the one where he ended up, he observes distance and nearness; a couple of square feet of pavement occupied by a beat-up, discarded phone book and a few bits of broken glass on one page could be as vast as the miles of sweeping wilderness on the facing page. A spindly rock formation is as imposing a figure as a human being whose face is concealed in a hoodie. In a lyrical text inserted as a single sheet, Ordóñez defines himself as “an outsider, / an observer and collector.” What does he collect on his “path of changes, fragments and chances”? Tangible impressions of intangible experiences, durable evidence of the transient, I’d say.

Cristian Ordóñez, On Trial, published by acb press, 2022. © acb press. © Photo: Cristian Ordóñez.

Cristian Ordóñez, On Trial, published by acb press, 2022. © acb press. © Photo: Cristian Ordóñez.

Cristian Ordóñez, On Trial, published by acb press, 2022. © acb press. © Photo: Cristian Ordóñez.

Cristian Ordóñez, On Trial, published by acb press, 2022. © acb press. © Photo: Cristian Ordóñez.

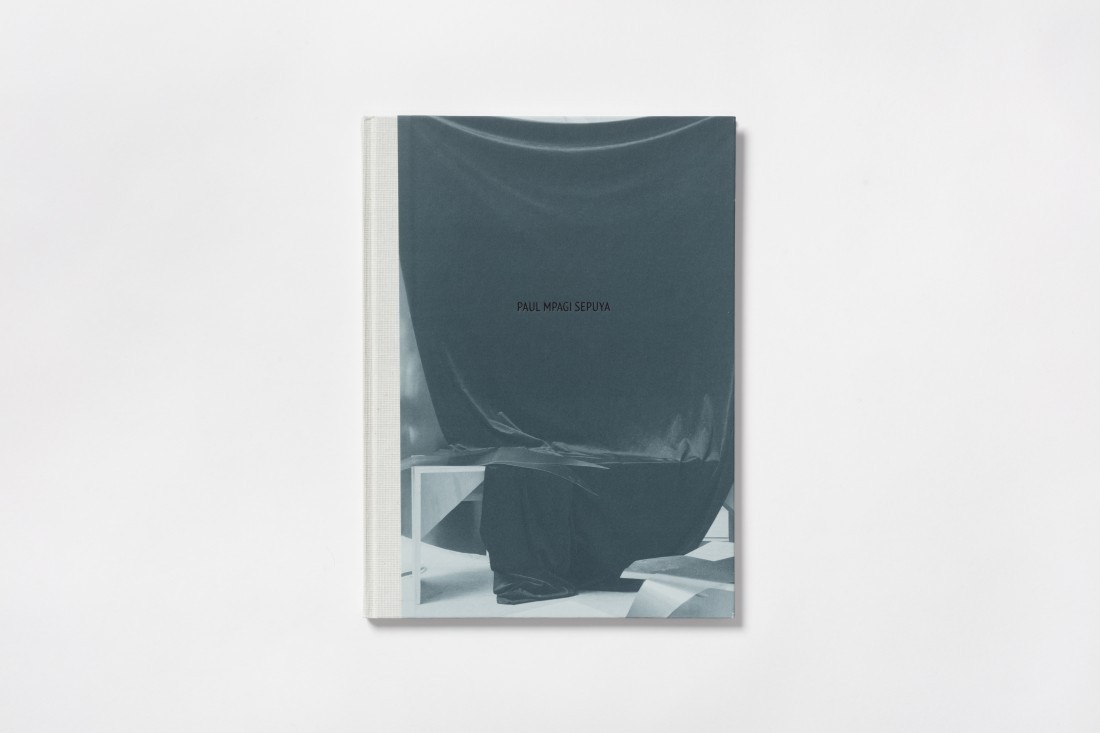

Bitner, Mueller, Ordóñez all ventured out to make their pictures. Paul Mpagi Sepuya, by contrast, is emphatically a studio artist. And in his recent book Orifice + Aperture (TBW Books, San Francisco, 2022; edition of 500)—meticulously designed by TBW’s Paul Schiek—Sepuya not only makes his Los Angeles studio an active element rather than a neutral background in the construction of his images, he also makes the camera itself a protagonist in their implicit narratives. And they do imply narratives, despite his giving them determinedly neutral titles like Studio, Screen, Framing Study, Darkroom Mirror Study, or the like. That’s because the camera is just one of the leading characters in these studies, while the others are naked men, mostly faceless, occasionally pictured singly but more often in pairs (and the pairs are generally interracial). So is this work about cool formalism or hot erotic fantasy? Both, neither, or better yet mix them up: hot formalism and cool erotic fantasy. And why, after all, would we want to separate critical intellect and carnal desire? A follower of DH Lawrence might object that it’s all “sex in the head,” insufficiently wet and grubby, maybe too far from consummation, but these pictures remind us that the mind is where the body becomes interesting. Sepuya has declared his interest “in how visualised racial difference works in pictures and how representations of queer and homoerotic acts get to the fundamental and underlying formal, technical and historical processes that make up photography.” It’s a lot to handle, but he does it with delicacy and candour. His work is oblique and frank at the same time. Detached glimpses convey so much, but the structure of interpretation is determined by the viewer’s desire.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Orifice + Aperture, published by TBW Books, 2022.

_Screen_(0X5A3785)__2020__40_x_60_inches_copy_1100_1650_90.jpg)

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Orifice + Aperture, published by TBW Books, 2022.

_Screen_(0X5A8295)__2019__40_x_60_inches_copy_1100_1650_90.jpg)

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Orifice + Aperture, published by TBW Books, 2022.

_Studio_(0X5A8715)__2020__13_x_9_inches_copy_1100_733_90.jpg)

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Orifice + Aperture, published by TBW Books, 2022.

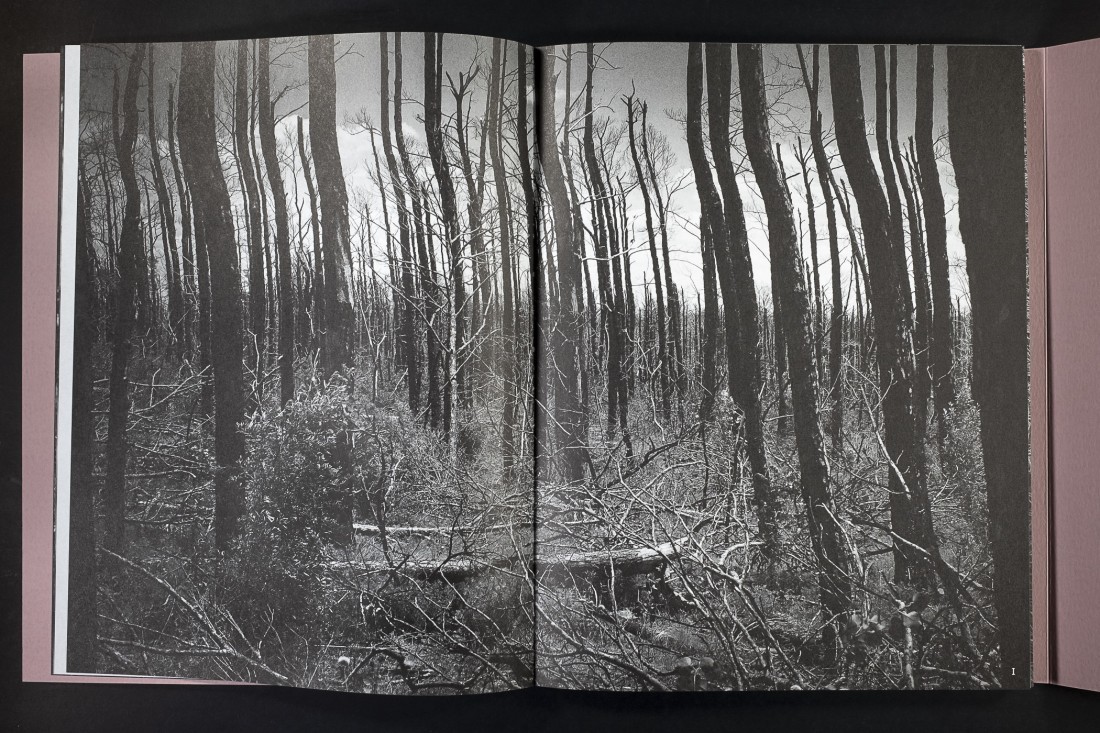

The wraparound cover of Barry Stone’s Lost Pines (self-published, 2022) encloses dense, mostly full-bleed black and white images that plunge the viewer into the thick of a forest. Eight inserted colour images, like small posters folded in four and printed identically on both sides, show seven Polaroid photographs and a copy of a card bearing an “A.A. Meditation,” the famous prayer beginning “God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,” placed in similar woodsy settings, as well as another insert, a small 12-page booklet whose front and back covers are a monochrome photograph of a threateningly cloudy sky while its interior contains deeply shadowy colour images of a domestic interior, part of which has been destroyed in a re. In other words, Lost Pines is not so much a book as a multipart book-construct that asks particular care of its viewer/handler, and a willingness to shift focus.

Barry Stone, Lost Pines, self-published, 2022.

Barry Stone, Lost Pines, self-published, 2022.

Barry Stone, Lost Pines, self-published, 2022.

Barry Stone, Lost Pines, self-published, 2022.

To get a handle on what you are seeing in Lost Pines, and why, you have to go to what is literally its back story, the account given on the last interior page of the bound book itself, which explains that “Lost Pines” is the local name for a vast forest not too far from Stone’s home in Austin, Texas, and which in 2011 suffered a devastating wildre; the next year, Stone began photographing there, immersing himself in the destruction but also in the forest’s slow recovery. The Polaroids shown in the colour pictures, however, are remains from a different re: one that in 2002 consumed the trailer in Magnolia, Texas—about a hundred miles east of Bastrop—in which his grandfather lived and died. The Polaroids were found in the wreckage, while the pictures in the booklet of the destroyed trailer’s interior came from undeveloped film Stone found in a drawer 20 years after the fact: “I don’t remember making those pictures,” Stone writes. The dimness and opacity of memory and the uncertainty of our hold on temporality—or maybe of its on us—are poignantly embodied in this book. ❚

Barry Schwabsky’s recent publications include a monograph, Gillian Carnegie (London: Lund Humphries, 2020), and the catalogue for the retrospective exhibition “Jeff Wall” at Glenstone Museum, 2021. His new collections of poetry are Feelings of And (New York: Black Square Editions, 2022) and Water from Another Source (New York: Spuyten Duyvil, 2023).