“Folklore and Other Panics”

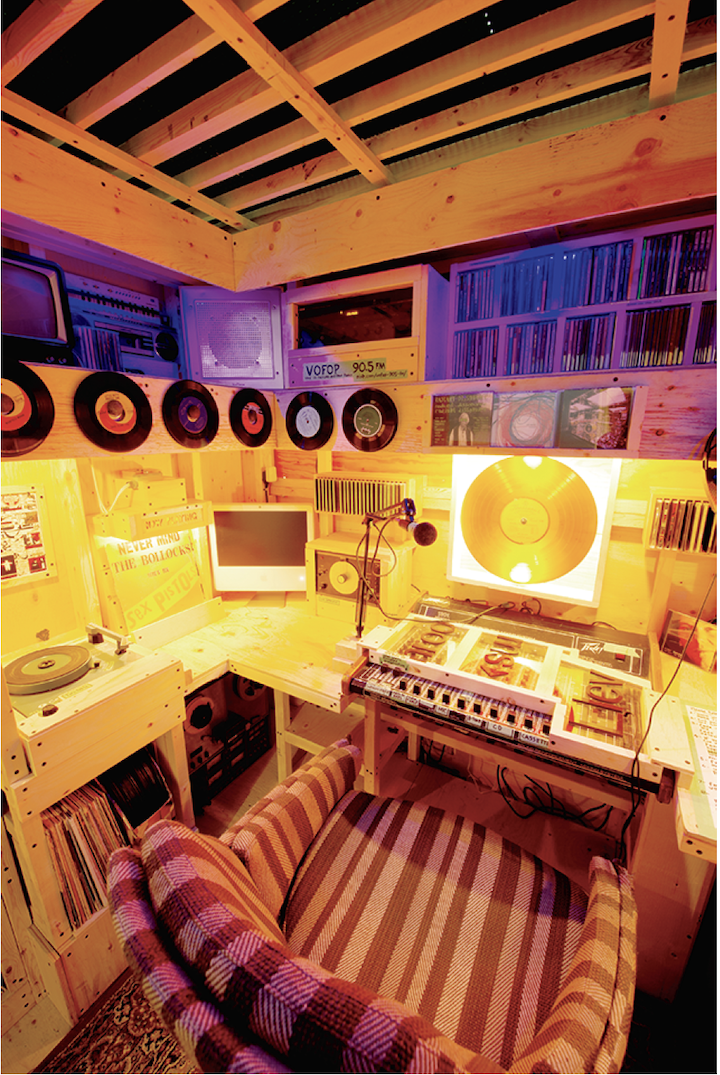

Just inside the entrance to “Folklore and Other Panics,” a tangle of children crowd into Michael Waterman’s Pirate Radio installation. They scratch vinyl records, play an instrument made from the bendy hose of a vacuum cleaner and try to figure out how to work the 8-track player. Though it smells like freshly cut wood, the room looks like the vintage basement of a music-lover’s dream. Custom-built shelves hold cassettes, CDs, amps and speakers. A microphone is jerry-rigged onto the articulated arm of an old desk lamp and a single, translucent red LP glows under a spotlight. The signal from here is broadcast online and over the air, something the children are thrilled to discover, tuning the handheld transistor radios provided. A few adults hang back, out of the fray. Nearby, a sign on the wall asks visitors to be courteous, and reminds us that the views expressed on air are not those of the museum.

On the wall opposite, paper globes are flattened and framed between glass—a collection of artifacts from artist Kay Burns’s alter-ego, Iris Taylor. An anthropologist and member of the Flat Earth Society, Taylor’s research is based at Brimstone Head, on Fogo Island, off the coast of Newfoundland—a spot said to be one of the corners of the flat earth. The globes were stomped as part of induction ceremonies for new members of the society, a symbolic break from structures of received knowledge and an affirmation of personal observation.

Installation view, “Folklore & Other Panics,” 2015, The Rooms, St. John’s, Newfoundland. Mark Clintberg, Passion over reason / la passion avant la raison, 2014, fabric and thread. Janice Wright Cheney, Coy Wolves, 2010, textile over taxidermy forms, found fur and accessories. Image courtesy The Rooms.

A wall-mounted vitrine holds an artifact created by Michael Flaherty—a ceramic caribou antler painted with an ornate image of a collapsing house, one of the oldest built structures on the Grey Islands, off Newfoundland’s northern peninsula. Where the animal’s skull should be, a white teapot appears, fused to the bone. Ceramics are some of the most common traces left by human settlement, and the Grey Islands were abandoned in 1961, when residents were resettled to larger, more central communities. Caribou herds have since thrived in the area.

Caribou also feature in the wallpaper designed by artists Kym Greeley and Erika jane Stephens-Moore for the newly built Fogo Island Inn. Instead of a decorative motif imported from somewhere else, this pattern reflects the sparseness of the barrens around the luxury hotel. On pale blue ground with occasional hints of vegetation, caribou wander, and the occasional animal stares straight out from the wall, confronting the viewer. These animals are not just local wildlife but powerful symbols, the emblem of the Newfoundland Regiment—the first five hundred soldiers sent to the First World War and subsequently decimated. The economic, political and cultural consequences of this loss to such a small community still resonate today.

Wildlife and luxurious trappings of civilization are at odds in the visceral work of Janice Wright Cheney as well. Three lean, taxidermal wolves upholstered in rich furnishing fabrics are poised throughout the gallery, ready to pounce. They are draped in jewellery, lace and mismatching furs—a collar, a muff, a stole and in one case, a full pelt, complete with tail. This wolf backs away, triumphant with a mouth full of black lace.

Installation view, Steve Topping, Floating Table, 1998–ongoing, door, modified fishing floats, drawings by various artists. Jerry Ropson, as spoken in tongues, 2015, mixed-media wall drawing. Courtesy The Rooms, St. John’s, Newfoundland.

Mark Clintberg revisits Joyce Weiland’s iconic quilted work, Reason Over Passion, with his response, Passion Over Reason. Made in collaboration with local quilters as part of a residency on Fogo Island, the work is precise and muted. Thin strips of printed cotton from various vintages are pieced together to form both the background and block letters of the text. A consideration, perhaps, of the dilemma often faced by residents of Fogo, and similar remote communities. Is passion what keeps them at home, when moving away might be far more practical?

At the centre of the room, a table made from an old door, with heavy legs of reclaimed wood painted bright red, sits under a single bulb hanging from the ceiling high above. The surface is covered in layers of drawings by local artists; doodles from more than 10 years of weekly poker games. The table was transported from a nearly derelict fishing stage perched on a cliff overlooking St. John’s harbour and preserved to museum standards. This is an installation by Steve Topping, one of the artists who played, and recently purchased the stage in order to refurbish it.

A wall drawing by Jerry Ropson spans the entire width of the gallery. Negative space is the overwhelming element of the composition, an indication of the vast landscape Ropson is attempting to capture. Water and sky are punctuated by a cluster of fishing stages, dark rocky hills and the floor along the wall is dotted with puddles of black ink. Like a vast legend to the diagram of this settlement, Ropson has added a list of hundreds of snippets of conversation: “232. she was some mad at her… 555. I do have something in mind… 418. feeling so friggin’ quilty does it matter how it looks?”

Michael Waterman, Pirate Radio, 2015, radio-station installation. Courtesy The Rooms.

Duane Linklater attempts to insert his own perspective into accepted discourse with Sunrise at Cape Spear Newfoundland. After learning about the disappearance of the Indigenous Beothuk people from Newfoundland in the 19th century, the artist made his way to the most easterly point in North America. Since then, he has been adding the paragraph “At 6:24 am NST 3/11/2011, Duane Linklater watched the sunrise. He travelled there to see the sunrise, to be the first before anyone else” to the Wikipedia entry for Cape Spear. Each time he adds this information, the community of Wikipedia editors removes it. Their messages to him, ranging from friendly advice to name-calling, are spelled out in vinyl letters on the gallery wall.

Guglielmo Marconi theorized that if sound decays incrementally, it could be possible to hear the past, if you listen closely enough. Joshua Bonnetta’s two-channel video projection explores this notion with the juxtaposition of sound recordings of current day radio signals made at each end of Marconi’s first transatlantic radio transmission in 1901. Film of Poldhu, Cornwall and Signal Hill in St. John’s reveal remarkably similar landscapes of ancient, moss-covered stone and crashing waves, adding a physical dimension to the signal’s path.

The gallery is anchored by another gathering place. Lee Henderson’s installation, “The Known Effects of Lightning on the Body,” is a small, knee-high video projected onto a sheet of polished copper, surrounded on three sides by low wood benches. One after another, a match in the centre of the screen is lit by another from above. Each burns out at a slightly different rate, charring and bending, only to be replaced. Given the title, it is possible to anthropomorphize these figures, but the campfire-like atmosphere created in the installation suggests something more akin to the renewal of energy within a community and people gathered around the glow of a tiny but powerful light.

Though strongly connected to Newfoundland and Labrador, “Folklore and Other Panics” illuminates broad contemporary concerns. We give ourselves so easily to authority, whether legal, economic or cultural. Every day, we have ample opportunity to negate our own abilities, our stories and our relationships with each other for the sake of comfort and convenience. This exhibition clears a space, both physical and conceptual, to gather and consider something else, to talk and listen and play. ❚

“Folklore and Other Panics” was on exhibition at The Rooms, St. John’s, from January 17 to April 26, 2015.

Jennifer McVeigh is a writer and editor living in St. John’s Newfoundland.