Barry Schwabsky’s PictureLibrary: Fine Focusing

Donna Ferrato, Diana Michener, Moyra Davey, Lee Materazzi

Among the marvellous things about books is that they can contain more or less anything, as long as it packs flat, like at Ikea. And two-dimensionality is something words and pictures have in common. Also in common: images change as they come into contact with each other, just as words do. A photograph in a photo book is no longer a self-contained image bordered by a frame that keeps the neighbours out. The resulting discourse of, or in, images has become ever more fascinating to me. This column, PictureLibrary, proposes to share some of the photo books that capture my attention as a way of thinking them through for myself.

Donna Ferrato’s Holy (powerHouse Books, Brooklyn, 2020) caught my eye before I’d even opened it—the red and black scrawl of the cover and even the red edge-painted pages promised an emotionally hot experience with the vehemence of a manifesto. The contents (blunt, dynamic black and white photographs and lots of mostly handwritten text) more than lived up to the promise. Packing into less than 180 pages a lifetime of work, 1976 to the present but according to intuition rather than chronology, it embodies Ferrato’s fervent belief in her own personal “trinity—the mother, the daughter, and the others who believe in women.”

Donna Ferrato, Holy, published by powerHouse Books, 2021.

Individually, Ferrato’s images tend to have multiple, non-hierarchical, even contradictory centres of attention; their energy is centrifugal. The way she’s smashed them together in the book increases the energy exponentially. It can be ferocious. Ferrato has been drawn to extremes, from survivors of domestic violence (as in her well-known 1991 book Living with the Enemy) to explorers of the further reaches of sexual experiment. But the point is not to fetishize life at the margins; what I take away from Holy is the sense that every feeling, every experience is in some way extreme for the person who feels or experiences. Danger lives in close proximity to joy. Not many books—of poetry or prose any more than of images—are so encompassing of the range of human passion or so clear in their demand, which journalist and editor Claudia Glenn Dowling expresses in her foreword as a call for nothing less than “another revolution into a future beyond the binary.” I’ll say amen.

If Ferrato’s vision is compounded of propulsive movement, Diana Michener’s Trance (Steidl, Göttingen, Germany, 2020) tends—as its title would suggest—toward stillness. This large-format horizontal volume opens with an epigraph by Henri-Frédéric Amiel, the obscure 19th-century Swiss writer who became famous for his posthumously published Journal intime: “Any landscape is a condition of the spirit.” There follow, mostly just on right-hand pages, about 50 monochrome images, all rendered somehow equivalent by their scale (12.75 x 10 inches) and hypnotic attention to minute detail. Where were they taken, what are their subjects? Happily, the book gives no caption information—no places, no dates. Yes, this is landscape photography, but Michener seems to be asking us to think not so much about specific places in the world as about the condition of the spirit that each place might cultivate in us if we could and would only look as carefully, unpossessively and non-judgmentally as Michener’s camera does. In that sense, these pictures function as something like mandalas, albeit far from geometrically ordered. Full of movement, yes, but movement as if from the perspective of eternity, where it is movement no longer.

Diana Michener, Trance, published by Steidl, 2021.

One writer of the early 20th century received Amiel as “an apostle of nirvana.” Michener, in the two-paragraph statement that closes Trance—practically the only text beyond that epigraph—describes her desire to work “where people and houses were absent,” and I suspect she was in search of her own absence, too. Her words are unusually eloquent: she speaks of finding a vastness “where the sky melts far away. I could not calculate distance. I didn’t have any destination, or point of reference. From here to there had no meaning. This uncertainty made me dizzy.” This dizziness is different from the terror that Cartesian rational space had evoked in Blaise Pascal (“Le silence eternel des ces espaces infinis m’effraie”) because the discomfort and anxiety it provokes herald a potential continuity between observer and observed, consciousness and the space in which it is (momentarily?) lost.

Another recent book by Michener, Twenty-eight Figure Studies (Steidl, 2020)—although smaller in format than Trance and softcover rather than clothbound—proceeds with a similar deliberate, formally restrained rhythm: all but the first of the, again, monochromatic images are 5.25-inch squares. But far from the meditative equanimity of the Trance landscapes, these Figure Studies are all ablur, as if seen out of the corner of an eye, or by someone turning their head away or toward what they think they’re seeing. And what are they seeing? Naked bodies, mostly in close-up, mostly in motion, distorted, hard to discern. Here one might be suddenly closer to Ferrato’s tumultuous world, but where Ferrato is explicit, confrontational, Michener is oblique, strangely even almost averse to her chosen subject matter.

As with Trance, again, no caption information, just a couple of paragraphs of afterword, in which the artist explains her difficulties in making this work. It’s revealing that what for other photographers would have been a help was for her an impediment: “the problem is the positions of sex are very visual.” She wanted something beyond the visible. How to find it? “I haven’t completely given up on it, but now it’s a little difficult at my age”—Google informs me she was born in 1940—“to go … I don’t have the same … oh forget it.” I admit I find her tongue-tiedness enchanting. The Steidl website explains what she can’t bring herself to say, that rather than trying to push her lens in among copulating couples, she resorted to rephotographing stills from porn movies. But no porn movie ever looked like this, I suppose.

There are a lot more words in Moyra Davey’s new book than in the recent two of Michener’s—not only her own five-page afterword and a note by Stephen Koch, but 14 beautiful pages by Eileen Myles, half essay, half poem, as an introduction (though I wish they’d come in the middle, and that photographs had opened the sequence). Yet there is a chariness of information that reminds me of Michener’s books—there are captions, yes, but by keying them by page number to images printed on pages that lack numbers (very faint page numbers occur, but only on imageless pages), Davey seems keen to thwart their use. Her book is called The Shabbiness of Beauty (MACK, London, 2021) and it juxtaposes 26 of her own photographs, dated between 1984—the year of her first solo exhibitions, in Ottawa and her native Toronto—and 2019, with 29 by Peter Hujar, made between 1957 and his death from AIDS 30 years later.

Lee Materazzi, Not No Touching, published by Quint Editions, 2021.

The book is a by-product of a Berlin exhibition that was briefly open last year before COVID shut everything down; Davey rightly reflects that it was “a risky act” to show her work alongside that of her esteemed precursor. She writes of herself as a product of “the post-modern era … self-consciously trying to signal what’s going on behind the camera,” whereas “Hujar was the opposite,” giving his all to the image as such. That idea—I’m not sure it’s true—is what makes it so interesting to notice that Davey’s every effort in this book has been to downplay all visual differences between their styles. Both artists show an existence that is essentially mysterious and luminous; and if Davey, an excellent writer, has developed an elaborate, and elaborately selfquestioning, discourse in tandem with her images, in contrast to Hujar’s tight-lipped ways, well, her images are just as capable of creating a hush.

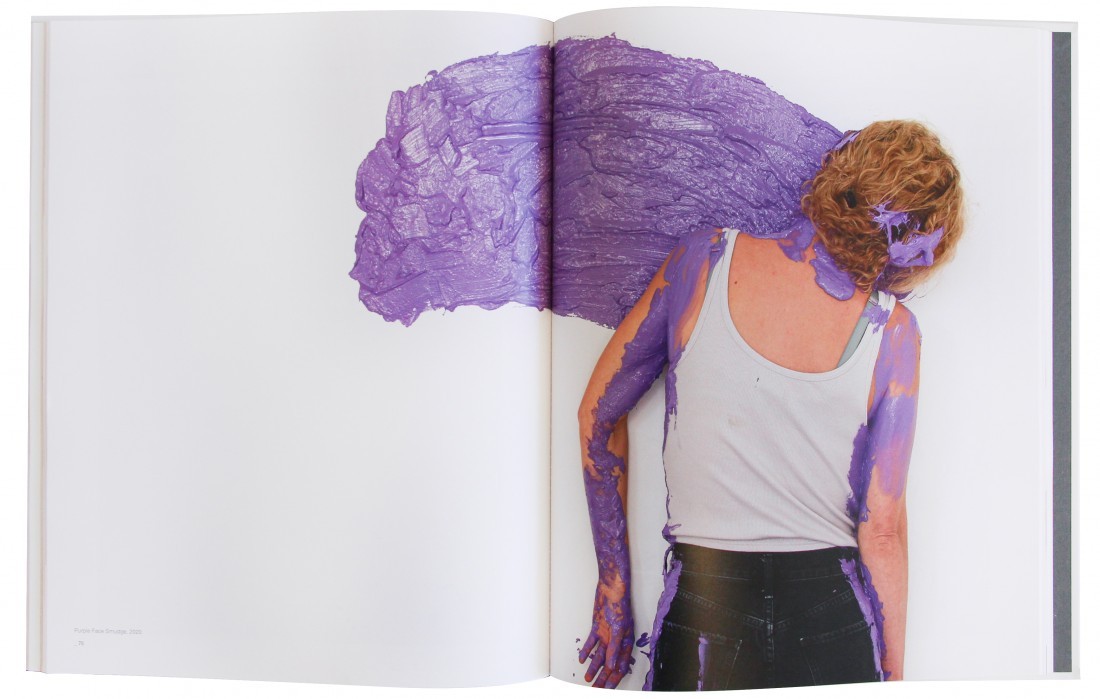

I don’t how it turned out that I’ve been writing about books with grey-scale imagery—just three of Hujar’s photographs in The Shabbiness of Beauty aside. All the better that I find myself ending with publications by Lee Materazzi. An artist about whom I know little, she makes photographs but thinks more like a sculptor who thinks more like a painter who thinks more like a performance artist. In the images in her ironically titled Not No Touching (Quint Editions, San Diego, 2021), everyday objects (fan, folding chair, buckets, paper towel rolls …) and a body, presumably that of the artist herself though always rendered more or less anonymous, are transformed, denatured and endowed with deliciously artificial presence through the generous fluidity of paint—as for instance in the image reproduced on its cover, in which a pair of arms, slathered in deep blue, pull across a white surface, leaving long, wet, drippy finger marks on a white surface—smeared lines that by the same token give the illusion that the active hands themselves are being wildly elongated by this act of primal markmaking. There’s a feral humour here, but it’s not unconnected to a dead-serious sense of need—“as if the / panic of days / could erase you / glossy depiction,” as Jasmine Kitses writes in one of a series of poems dispersed among Materazzi’s pictures. I thought I better understood the reason for that when I read the note in the back of the book explaining that the book “contains work that has been made in part with her two children” while they were between the ages of four and eight—“Throughout this book there are many of their works and marks.” Yeah, I remember how at that age kids could mark you, too.

Also by Materazzi is a related publication, Testing Focus (self-published, San Francisco, 2021; edition of 100)—a small, stapled brochure of colour copies of, indeed, “photographs taken to test focus,” according to the artist’s website. I can tell you the focus looks just fine. The informality conveys an even more vivid sense of how resourceful she is as a surrealist of daily life or documentarian of a fantastical relation between the human and materials—another, very different avatar of that “bright spirit of curiosity and erotic transgression” that, according to Dowling, Ferrato’s work augurs.❚