Ellen Gallagher

Ellen Gallagher’s most powerful modes are melding racial stereotypes into abstraction in a way that resonates with historical archetypes even as it moves beyond them, and using a fantasy of black history and the deep sea world as a stand-in for the subconscious. Those themes meld well, and she’s hit on three convincing streams of work to explore them.

First, race and abstraction: Gallagher, who has a Cape Verdian father and an Irish mother, came to prominence in the 1990s with apparently abstract paintings. On closer inspection, these turn out to consist of what she calls “the disembodied ephemera of minstrelsy”—goggle eyes, hotdog lips and Afro hair—on the blue-lined “penmanship paper” used in schools for writing practice. The effect is an Agnes Martin look, which—far from the would-be-pure tremor of a meditative aesthetics—is built on a racially divisive educational system and set of representational conventions. So, a serious point, but also rather funny, especially in the sculpture Pinocchio Theory, 1996, in which the pickaninny smiles spread across what could be an elongated nose.

Ellen Gallagher, Afrylic, 2004, Plasticine, ink and paper on canvas, 96 x 192 inches. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery, © Ellen Gallagher.

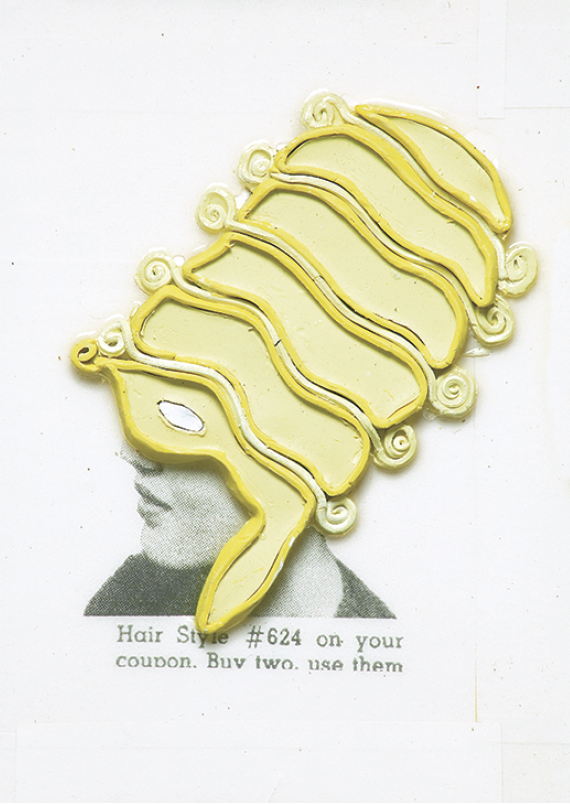

Second, Gallagher hams up that race-meets-abstraction ploy with more explicit social history and a twist of fantasy. Witty collages led to five monumental yellow paintings, of which Double Natural, Pomp-Bang and Afrylic are here. Each presents a grid of some 400 heads taken from 1930s–’70s adverts in black-oriented magazines, all embellished with yellow Plasticine—like wigs. The eyes are whited out, so no gazes distract us from the dance of the hair shapes, which are a triumph of wit and invention: impressively varied, appropriate to their hosts’ poses, and full of interest as bass-relief shapes. Looked at purely as an abstract “painting” of sorts, its third dimension just emerging from the grid, these are wonderful works.

There’s more here, though, as the hair straighteners and skin- lighteners advertised and the blonde wigs imposed all speak to the sale of white stereotypes to blacks. They could also criticize a racially passive desire to fit in to the white world—yet remind us, too, of the assertive styling of the Afro. Those wig-shapes are at once doleful and upbeat, at the same time comical, childish and potentially dark; they could represent disturbed thoughts or physical distortions. Put them together and you have an abstracted sea of faces which aren’t quite faces. They suggest a lively community, but a disempowered one, its people not yet treated as individuals—but ready to change that.

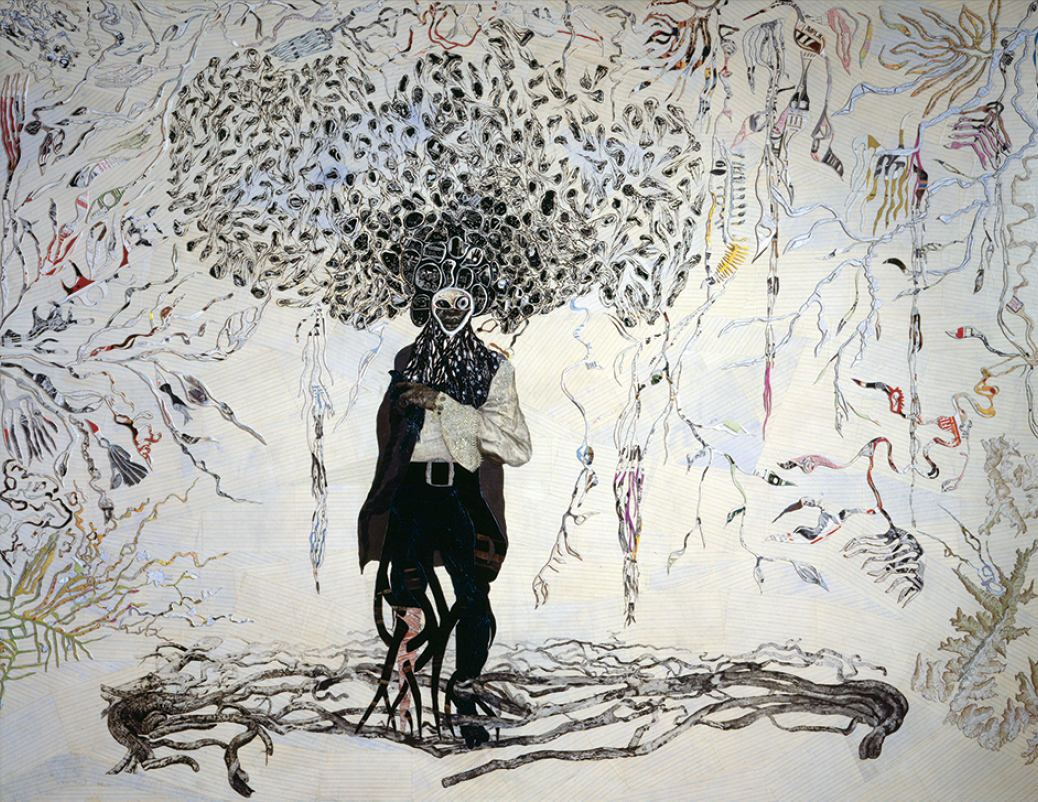

Ellen Gallagher, Bird in Hand, 2006, oil, ink, cut paper, polymer medium, salt and gold leaf on canvas, 120.875 x 93.75 inches. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, © Ellen Gallagher. Photograph: Mike Bruce.

Talking of the sea, the third rich seam is “Watery Ecstatic,” an ongoing series of watercolours and incised paper collages that conjure marine life with a vivid and quasi-scientific delicacy. Gallagher has worked in oceanography, and you could be in the realm of natural history painting until you spot that there are many human faces smuggled into the jellyfish, octopi, seaweed and eels. This plays off underwater as a metaphor for psychological depths—there’s plenty of Freud in Gallagher, and indeed her 2005 show at London’s Freud Museum turned on his early fascination with marine life. “Watery Ecstatic” also introduces the mythic world of Drexciya: a black Atlantis founded by pregnant women thrown overboard from transport ships, who bore children who could breathe underwater. This is a 1990s Afrofuturist creation of the musician James Stinson, who imagined the Drexciyans as warriors. Gallagher’s version is more positive: she says her ex-slaves are “carriers of ideas of regeneration and ideas of trans-historical nation,” which fits with the watercolours’ language of cellular growth. In all of this, a starting point of suppression gives way to a surging forth: minstrelsy insinuates its way into the dominant culture’s modes of abstraction; burlesque comedy counterpoints—even as it emphasizes—social constraints; dark histories rise from the seas in a fantasy of liberation. So, an uplifting and incisive three-part presentation of the essence of Gallagher.

Not quite, for that’s half, at most, of an 11-room show, and I found the rest rather got in the way. Some of the literariness and would-be-mythical musing just didn’t gel for me: the use of Exodus, Freud’s passion for Egypt, a one-legged tap dancer, the gold circuit-board making silhouettes of dandies, the whale cycle Osedrax. Others didn’t convince me aesthetically: when collage gets too baroquely clotted (whether figuratively in Bird in Hand or near-abstractly in Puppy Chowder); when the two-sided drawings of Morphia fail to deliver on the promise of an effective to and fro between recto and verso; when film installations get lost in elaboration…Really, I could have done without them all. Perhaps, though, that’s not wholly a function of comparative quality. It’s the quantity, too; with so many works in need of different, detailed contextualization, it starts to feel like hard work. And so, one is driven to select—those three primary approaches which form a very fine show within the show.

“Ellen Gallagher: AxME” was exhibited at Tate Modern, London, from May 1 to September 1, 2013.

Paul Carey-Kent is a freelance art critic in Southhampton, England, whose writings can be found at <paulsartworld.blogspot.ca>.

Ellen Gallagher, Watery Ecstatic, 2005, watercolour, ink, oil, varnish, collage and cut paper on paper, 32.625 x 42.375 inches. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, © Ellen Gallagher. Photograph: Mike Bruce.