Directing the Truth: An Interview with Albert Maysles

Salesman, the 1968 feature-length documentary by Albert and David Maysles, a landmark in American cinema, remains one of the finest documentaries ever made. It is a classic example of Direct Cinema, a style of filmmaking with no interviews, no narration and no manipulation of the truth; the film is found in the shooting. “Drop word logic and find a dramatic logic in which things really happened” was the way Robert Drew, an early proponent of the technique, put it.

Salesman is about four men who go door-to-door attempting to sell expensive Bibles to people without the money to buy them. Paul Brennan, the most gregarious and least successful of the quartet, moves from having little confidence to displaying plenty of despair. “This is ball-breakin’ territory,” he says at a particularly low point. He has pulled out all the tricks, even trying his various impersonations of being Irish, what he calls derisively, “all the old mickey stuff.” Brennan is a real-life Willy Loman, at once sympathetic and pathetic. He is the focus of Albert Maysles’s favourite scene, in which the young daughter of a woman, who is as committed to not buying a Bible as Paul is to selling her one, goes over to an upright piano and plays a bit of music that is a perfect sounding of Paul’s despair. “The kid knocks out a tune which Beethoven couldn’t have composed any more appropriately,” Maysles says in the following interview. His great instinct as a cinematographer is that he kept his camera rolling. It is an instinct he has acted upon for 57 years, from Psychiatry in Russia, his first film, shot in Soviet mental hospitals in 1955, to In Transit, a film composed of stories he discovers while travelling on the world’s long-distance trains.

Albert Maysles, still from Psychiatry in Russia, 1955, 16-mm film, black and white, 14 minutes. Copyright Albert Maysles. Images courtesy Maysles Films Inc. photo collection, New York.

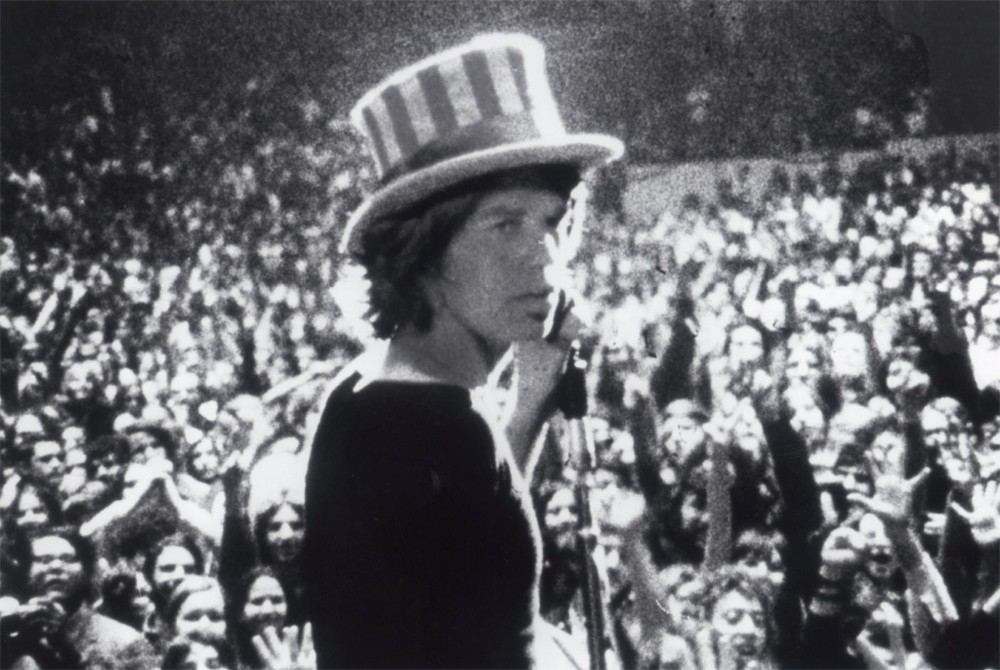

The Maysles Brothers worked together from 1957 until David’s death in 1987, and for the last 25 years, Albert has continued to make remarkable documentaries. During their collaboration they shot and directed a string of indispensable films, including Gimme Shelter, 1970, Grey Gardens, 1976, Running Fence, 1978, and Muhammed and Larry, 1980. The subjects were various; the technique was singularly unchanging. Gimme Shelter started out as a concert film about The Rolling Stones Altamont concert and ended up as the forensic record of a killing. If Woodstock was the apogee of the ’60s; Altamont was the decade’s dark conclusion, and the Maysles and their camera were its unflinching witnesses.

In Grey Gardens they encountered an eccentric mother and daughter, Edith and Edie Beale, living in decaying circumstances in their once elegant and now dilapidated East Hampton mansion. An aunt and a first cousin to Jackie Kennedy, the two Edies are irresistible characters; you wouldn’t want to live with them, but you can’t take your eyes off them.

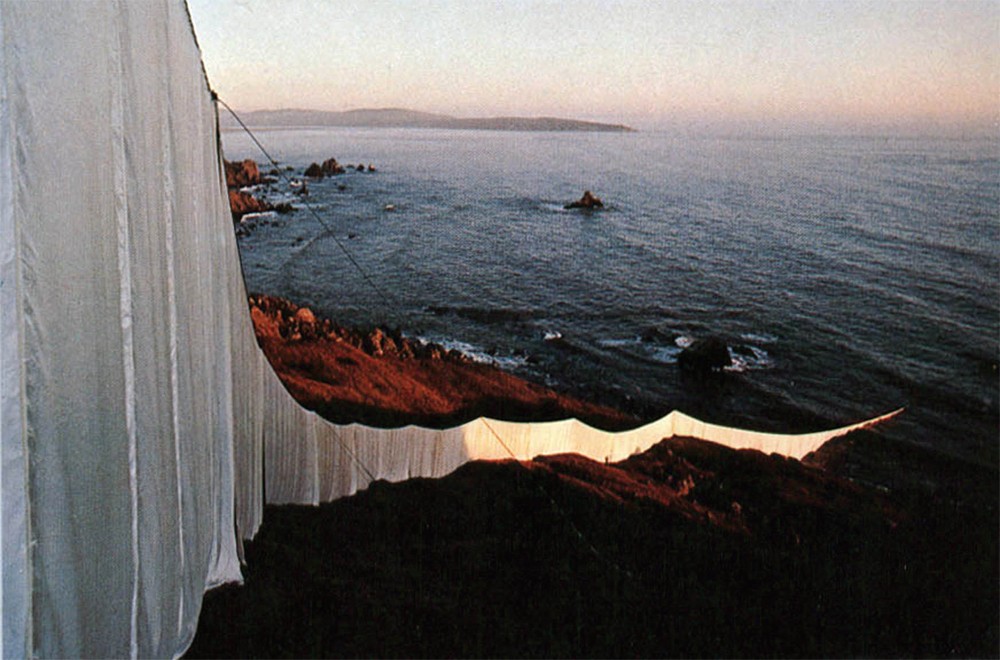

Running Fence is one of five films about the collaborative partnership of Christo and Jeanne-Claude, a pair of artists who realized massive projects in which the process was as important as the product. Before the fence runs its course across 24.5 miles of Sonoma and Marin counties in California, you see its many incarnations: at one moment a misty shroud, at another a billowing, bronze curtain, at yet another, a brilliant, white snake slipping into the Pacific ocean. “The eye of the camera is poetic,” Maysles says, and Running Fence is a dazzling example of that poetry in motion.

Maysles’s gift is for the intimate and the closely observed. His sense of detail is impeccable: the toes of Keith Richards’s snakeskin boots as he taps out the rhythm of Wild Horses in a recording studio; the radiant smile of a Cuban fisherman’s wife in her new government-supplied house; Jackie Kennedy’s hands held nervously behind her back as she faces a Polish community hall during the Wisconsin primary. The small gesture becomes emblematic, and then, revelatory.

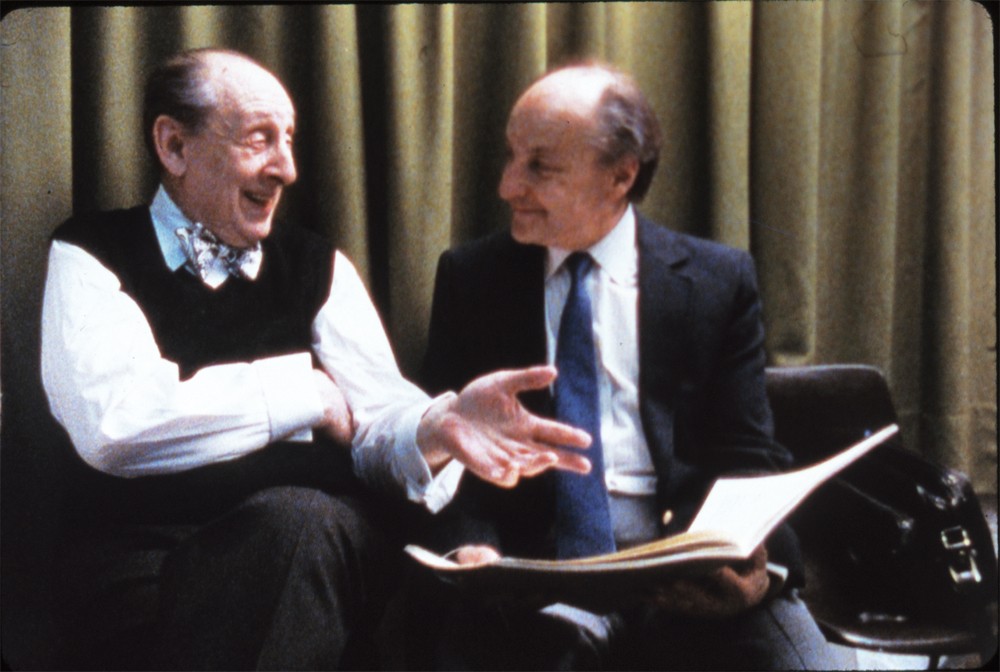

Maysles is especially sensitive to the way the face registers complete involvement. His father loved music, and as a young boy he claims to have received a full musical education watching his father listen to classical music. It is this sense of attention that characterizes many of his most compelling sequences. (He also has a flawless sense of duration; he invariably knows how long to keep filming, which is itself a kind of visual music). His films are a trace of our looking at people who are absolutely absorbed in what they are doing: Marlon Brando, Seiji Ozawa, Truman Capote, Vladimir Horowitz, Charlie Watts. Maysles’s camera appears, almost impossibly, to be invisible. What he comes up with is both found and captured; it exists in reality and equally in the discriminating lens of his camera.

In Capturing Reality, 2008, an NFB film about the art of documentary, Werner Herzog says, “There is an ecstasy of truth that is way beyond facts,” an observation that searches the documentary form for the line between what is demonstrably true and what is poetically possible. Albert Maysles life-long commitment to truth-telling situates him and his films, uncategorically, in that ecstatic order. Albert Maysles attended the “Gimme Some Truth” documentary forum held in Winnipeg from October 13th to 16th, 2011. He conducted a master class, and on consecutive evenings, introduced Grey Gardens and Salesman. He was interviewed by Robert Enright on October 14th. Border Crossings would like to thank the Winnipeg Film Group and DOC Winnipeg for their cooperation in facilitating the interview.

border crossings: You started out being a psychologist and after looking at your films, it occurs to me you never stopped being one.

albert maysles: Thank you. I guess psychology can get in the way, but it gave me the advantage of really wanting to discover what is going on rather than setting my mind on what I was going to get. I’m a person whose only point of view is not to have a point of view. I think that is very important.

What was the source of your interest in psychology?

When I was 12 years old I read a biography of Sigmund Freud, it was with a bunch of other famous guys like Descartes. I have always been fascinated with human behaviour. Then when I was 28, just after having taught at Boston University, I thought it would be interesting to go to Russia. I wanted to get into mental hospitals, and I decided to hitchhike to New York to see if I could get an assignment from Life magazine. I showed them photographs from a professional photographer, claiming they were mine, and they were impressed, but not enough to support me. Then, when I left the Life magazine building I saw CBS, and I ended up speaking to the head of the news department. They had no proof whatsoever that I could get into the hospitals, and I had never seen a movie camera, although I was good with a Leica, but they gave me a camera and film. They said, “Take the camera to Boston and shoot a roll. When you come back to New York, before getting on the airplane to Helsinki and Moscow, allow three hours for us to process the stuff.” That was my training. So I went to Russia on a one month visa. Only 400 Americans visited Russia in 1955.

Still from Salesman, 1968, 16-mm film, black and white, 91 minutes.

This is a time when relations between Russia and America weren’t what you’d call congenial?

I felt, as I do now, that it is important for us in America to have direct eye-to-eye relationships with people from another country. So I chose the psychiatry thing. I got to Russia, and a couple of days after I arrived I met Bill Worthy, a black guy who was a journalist for The Baltimore Afro-American, and I explained to him that I wanted to get into mental hospitals to film. I didn’t speak any Russian. He said, “Well, tomorrow I’m going to be at the Rumanian Embassy for a reception celebrating the takeover of Rumania. I’ll see if I can get you an invitation.” He couldn’t, as it turned out, but he said to come along anyway. So we get to the Rumanian Embassy and there are half a dozen KGB guys at the door. He shows his invitation, slips it back to me, and I show it. Then they ask to see my passport and it doesn’t match. The KGB guys are howling with laughter because they think this is the funniest thing they’ve ever seen, and they send me in. Within minutes I’m talking to the American Ambassador, and I get introduced to all these Russian heavyweights. When I told one of them what I wanted to do, he said, “We always think that the other one is crazy.” He was probably reflecting on his own paranoia. But before I left I had the telephone number for the head of psychiatry and I was given an open ticket. Today in America I could never get access to mental hospitals because of the privacy rights issue, but in Russia I could do whatever I wanted. I had my Leica and I also took still photographs while I was there.

Did the filmmaking bug catch you; was there something in filmmaking that suited you?

Yes. The only problem, looking back, was that it would have been so much better if I’d had a video camera, because each reel on the Keystone 16-mm camera had only three minutes of film, with no sound, so it was a terrible disadvantage. I had to heavily dose the film with narration so people could understand what was going on. I showed the film in Boston, and a year or two later I was living in New York and noticed in the newspaper that Mrs. Roosevelt was about to go to Russia to study social services. She wanted to visit mental hospitals but she’d heard there weren’t any, so I called her up—I don’t know how I got her phone number—and told her there are mental hospitals in Russia and I made a film about them. She asked to see it and I brought over a projector and showed it to her. We talked for the rest of the day and she said, “I’m leaving in three weeks and I’d love to have you come along.” I couldn’t, for two reasons: I didn’t have a camera, and even if I did, it wouldn’t have any sound, and it would have been crazy to shoot without sound.

The whole trajectory of how you became a filmmaker is almost like fiction.

You’re right. I’ll tell you how I met my wife. When we made Salesman in 1968, one of our purposes was to break through the prejudice against the form. We wanted to make a true feature, so we chose these door-to-door guys. We had a screening with, maybe, a hundred people to raise money, and there was this one person at the back of the theatre. As she got up to leave I noticed that she had been crying, and as she got close I saw how attractive she was. I elbowed my brother and said, “She’s for me, that’s my wife.” She was moved by it because it is the embodiment of Death of A Salesman, especially by Paul Brennan, “The Badger,” who is a tragic figure.

But how was the camera so invisible in that film? Every once in a while one of the characters will talk to you, but the invisibility of the camera, and the intimacy it generates, is unprecedented.

Part of it is that both the salesmen and their subjects are so wrapped up in what is going on; the woman is trying not to buy and the salesman is trying so hard to sell. But being able to film without the people being distracted by the camera just happened. I’m already filming at the door. Either the salesman or my brother would explain that we were making a film, and if it was okay with them, we’d like to do some filming. We used to say it might get on television.

Were both you and your brother good at being invisible?

Actually, my brother was more visible because the camera wasn’t hiding half of his face, so it was very important that he had a manner where people would not be distracted. We didn’t start working together right away. When I did the psychiatry film I went to Russia alone. Then, in the late ’50s, my brother was drafted into the army, and when he was in Europe he met up with a guy whose uncle was Milton Greene, the famous still photographer of Marilyn Monroe. His friend said, “when you get back to New York, look up my uncle,” which he did, and he got a job as Milton’s assistant. It was when he was working on the Monroe films, first out west and then in England—I think it was The Prince and the Showgirl. So that was his introduction to moviemaking. Then, in 1959, I met Bob Drew, Richard Leacock and Donn Pennebaker just at the time that they were about to do Primary. I was one of the cameramen. Ricky Leacock, Pennebaker and I did the filming and Bob Drew did the production.

Where did the idea come from to shoot behind Kennedy as he walks the long, congratulatory line into the auditorium?

In all truth, it was Pennebaker’s idea. He said, “I’ve got this extremely wide angle lens that nobody uses and it would be perfect.” My contribution, besides filming, was that I snuck around behind Jackie and filmed her hands. All the other cameras were on her face, which was right, but I got the hands, which was the only way to know how nervous she was. When she saw the film she said, “I have to save this and show it to my grandchildren.”

There is no way you could have known that Kennedy was going to win the Wisconsin primary. Hubert Humphrey was a serious candidate.

We were all determined to be unprejudiced in our filming, but if you’d asked us who we would really like to win, it would have been Humphrey. But just as with Bush being a member of the upper class, the lower classes prefer to have someone from an upper class representing them.

Was Primary a breakthrough film for you?

It was enormously important for my development. Initially I had a much better camera, and then I made my own camera, which I used for many years. I designed it so that it balanced on my shoulder with the battery and the magazine and all that other stuff over my shoulder. Lifting it was a strain, but once I got it up I could carry it there all day long. I did all kinds of things that made it much better. I had a little magnifying mirror up front so that I could read the aperture without putting the camera down, and I also had a Spectra meter up front so that I could read the exposure. I never had to take it off my shoulder.

You seemed to have a natural sense of composition.

Yes. The composition was very important.

Gimme Shelter, 1970, 16-mm film, colour, 90 minutes. Photographs: David Dalton.

Gimme Shelter, 1970, 16-mm film, colour, 90 minutes. Photographs: David Dalton.

Did you and the group you were working with on Primary clearly articulate the tenets of what became Direct Cinema? Were there rules, and did you adhere to them as much as you could?

Yes. Both Leacock and Drew had these notions. Bob was a photo editor for Life magazine, where he thought of this new way of filming with the picture and the caption, the caption being the soundtrack. This was the “No Narration and No Hosts and No Interview School” of filmmaking. You won’t see an interview in any of the films that we made.

Did those rules correspond to what you wanted to do with cinema at the time?

It was exactly the right thing. I thought, this is the way it has got to be. I didn’t need to be persuaded.

Did you know about cinéma-vérité in France, as well as what was happening in Canada at the National Film Board?

Neither of which was the pure, uncontrolled filming we were doing. It was in that same direction, but it wasn’t as far out as we were. It was Alfred Hitchcock who said, “In a fiction film, the director is God; in a non-fiction documentary, God is the director.” That was the idea: let it happen because you are in good hands.

John Grierson, who was extremely influential in the history of the NFB, defined documentary as “the creative treatment of history.” If you put the emphasis on creative, it gives you a lot of leeway; if the emphasis falls on history you are more in a traditional documentary territory.

I heard Grierson’s name over and over from Ricky Leacock, who hated him because he felt Grierson was limited by his political persuasions. I felt that way as well.

What I’m getting at is, how creative can one get, and how historical does one have to be in making a documentary?

The answer is Orson Welles’s statement that the eye behind the camera should be the eye of a poet. It’s a sensibility where you don’t desire to change anything, but you find things that people who are not artists would not even notice and, of course, you frame it in such a way that you get the essence. Many years ago through Bruce Davidson, a good friend of mine, I happened to meet Henri Cartier-Bresson, and when I got married he said, “take any one of my photographs,” and I chose Matisse with the white pigeons. It’s a perfect example of what I’m talking about. It would have been enough if Cartier-Bresson had focused on Matisse’s face, but pulling out and including the birds in the cage is what makes the photograph work.

Cartier-Bresson’s aesthetic captured the “decisive moment.” Filmmaking, of course, can’t be decisive. It’s kinetic, so it has to be a series of decisive moments.

Yes. I think my favourite scene of everything I’ve ever filmed is the opening scene in Salesman, where Paul Brennan is having a hard time pitching this woman who has a daughter on her lap. I kept on shooting, not knowing what is going to happen next, but the kid gets up, goes over to the piano, and knocks out a tune which Beethoven couldn’t have composed any more appropriately. That tune is so much what Paul is feeling at the time.

As his depression deepens, he begins to haul down those other guys. A fascinating dynamic develops as the film progresses. You must have been aware that what you were getting was an interpersonal drama of some considerable emotional intensity?

Albert Camus said that artists are at their best when what they’re depicting has some relationship to an early childhood experience. In the case of Salesman, Paul Brennan, in an obtuse fashion, is like my father. My father was a very sensitive person who became a postal clerk because he had to have an income to support the family. But he also played the cornet and could well have been a musician, just as Paul could have been an actor. In fact, a year or two after we made the film I got a call from him and he said, “I just got this offer to go to Spain for an acting job, but I turned it down because it wasn’t a big enough role.”

Your emotional investment in these people interests me. It’s clear that you sustain relationships with the subjects of your films. When you talk about remaining objective, I wonder how much distance you can sustain from people who are tragic, moving, pathetic, magnificent. How do you draw the line in the making of the films?

I know this sounds like a contradiction but somehow what I do is both objective and subjective. In a way that emotional involvement gets you that much closer to what is really going on, as long as you don’t tailor it with a point of view. My brother and I always agreed on everything, which was unusual. We had the same determination to get much as you could the real thing and to not impose ourselves on the situation.

David Maysles, Albert Maysles, Ellen Hovde, Muffie Meyer and Susan Froemke, Grey Gardens, 1976, 16-mm film, colour, 94 minutes.

You also stayed in touch with people. It’s as if filmmaking was a way of establishing and sustaining relationships.

We stay in touch with them and they stay in touch with us. We made Salesman over 40 years ago, and just last year we got a phone call from James Baker, “The Rabbit,” who now sells real estate, and he said, “I just made a sale for $4.2 million dollars, and I’m going to be in New York,” and he came to visit us.

In Orson Welles in Spain, Welles says that filmmaking is the most old-fashioned thing, because in his words, “We’ve been cranking it out the same way all along.” Were you conscious of breaking free of that cranking-it-out tradition?

Yes, especially that lesson in Primary. But I think even before that my still photography shared a combination of compassion and objectivity.

When you say that Paul could have been your father it’s a deeply personal admission. Was there always something in the films that touched on things that were close to you?

David Maysles, Albert Maysles, Ellen Hovde, Muffie Meyer and Susan Froemke, Grey Gardens, 1976, 16-mm film, colour, 94 minutes.

Here’s another example of my father’s influence. When I was a kid my father and I had the habit, maybe once a year, of going to the big closet and putting on his World War II uniform. I’d put on his shirt and he would put on his boots. When I was 9 or 10, I noticed that way, way back in the closet there was an old case of some sort. Somehow I knew there was a taboo connected to it, so I never said anything. There was one occasion when I noticed that both of us were looking at this case. So my father got the case, opened it, and took out a cornet. He put it to his lips, moved his fingers, and I could see from his embrasure that he knew what he was doing, but he didn’t play it. Then he put it back in the case and back in the closet. A couple of years later I was talking to my mother and I mentioned this episode, and she said, “Here’s what you have to understand. You know your Uncle Sam plays the violin, and your Uncle Joe used to play percussion, and you had an Uncle George, whom you never knew because he died before you were born, and he also played with your father. And when your Uncle George died, your father just didn’t have the heart to play anymore.” So I had always kept the cornet on the wall in the kitchen, and several years ago I noticed that it needed to be polished and I asked the housekeeper to polish it, and she must have dropped it because the front end was smashed. I brought it to my studio, not knowing what I was going to do with it and how I could get it repaired, and just at that time Wynton Marsalis comes to my studio to look at the film we had just made about him. I was about to tell him that story and he took hold of the cornet, moved his fingers, and played for 5 or 10 minutes. But thanks to my father, I had a whole course in musical appreciation from just looking at his facial expressions as he would play a recording of Beethoven or Bach. So when you see Vladimir Horowitz listening to the playback in Horowitz Plays Mozart [1987], that face and those hands were my father’s. That’s what drew me to get his expressions. Then in Gimme Shelter [1970], I go from one face to the other while The Rolling Stones are listening to Wild Horses. I spend so much time on Charlie Watts.

So the music was in you because of your father?

Yes.

How did the film with the Stones come about?

I got a call one day from Haskell Wexler, the cinematographer, who had just been talking to the Stones. He said, “they’re going to be arriving in New York in the next day or so and you might want to meet them.” So we went to the Plaza Hotel, and they told us they were performing the next day in Baltimore. We attended the performance and saw how good they were, and while we thought we could do a great concert film, it had to be something more than that. It turned out to be Altamont.

Were you ever frightened because of the chaos that was happening onstage?

Not really. I was just so determined not to miss anything. But talk about luck. I was on stage and my brother was just off the stage, a little bit to the left and out of my view. He happened to be on a truck and was able to see exactly the killing scene.

David Maysles, Albert Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin, Running Fence, 1978, 16-mm film, colour, 58 minutes.

The role of documentary as a form of witnessing interests me. That is a role you end up assuming at Altamont.

And you take on an enormous responsibility in shooting, editing and showing the film. People’s lives and reputations are at stake. So many reviewers attributed the killing to the Stones because of the title of one song, but the weird thing is the Stones weren’t playing Sympathy for the Devil when it happened; it was Under My Thumb.

What did you make of the review Pauline Kael wrote in The New Yorker? She seemed to suggest that the whole purpose of the film was so that you could use the sensational footage of the death.

We presented our response to what she wrote to William Shawn, The New Yorker editor, but he didn’t publish it, if only for the fact that they didn’t have a Letter to the Editor section in those days. With one example after another we made clear how she was wrong about our staging things. The most outrageous claim she made about Salesman was that we got Paul Brennan, who really sold roofing, to play the part of a Bible salesman. I immediately went to our lawyer and said, “What can we do about this?” and he said, “Nothing, because you have to prove malice, you have to be able to demonstrate that she knew it was wrong.” Anyone reading that article would think we had violated what we preached: that what is most important in making a documentary is to tell the truth.

Albert Maysles and Bradley Kaplan, Muhammad and Larry, 2009, 16-mm film and HD video, 52 minutes.

People play to the camera in very different ways. There is a huge difference between Paul Brennan and Marlon Brando, or both the Edies, especially Little Edie, in Grey Gardens (1976). She’s a born performer who wants the camera there all the time. In fact, there are many times when she is talking conspiratorially to the camera, whispering even. Clearly you let the character of the subject set the tone for the relationship they have with the camera.

People said that they were performing for the camera, but every day when we arrived to do the filming— we didn’t stay there because the smell was so bad—we would pull the car up behind the bushes and spray our ankles so that we wouldn’t get bitten by the fleas. As we were doing that we would hear them conversing with one another and it was exactly the kind of stuff we were getting.

So that was the nature of their life together?

Absolutely. And I’ll tell you, if we had gotten one frame of it wrong they would have let us know. They were Bouviers to the core. They loved it. When Mrs. Beale was dying Edie turned to her and said, “Is there anything you want to say?” and she said, “There’s nothing more to say, it’s all in the film.”

Albert Maysles and Susan Froemke, Jessye Norman Sings Carmen, 1989, 16-mm film, colour, 57 minutes.

What made you make Cut in 1965? It is such an amazing and frightening piece of art.

Yoko Ono’s husband at that time was representing her, and she was doing “Happenings.” He came to us as her agent and asked if we would film one with her. We said it would cost at least $300 for the film and the processing and he said he would pay for it, so we shot it. Years later we got a call from Yoko who said she wanted to buy the film, and she paid me $40,000. That’s not a bad wage for an hour’s work.

There is a moment in the film where you’re not sure how far that one guy is going to go in cutting what’s left of her clothing, or worse.

That’s the whole point. The whole audience could feel the tension.

Is it in 1973 that you do the first film with Christo and Jeanne-Claude? You become the official filmmakers for their projects.

I’ll tell you how that happened. We were at Cannes showing a film, and another showing was scheduled for Paris. An engineer we had met saw the first screening and he said, “I want to see you when you get to Paris, and if it’s okay with you, I’d like to invite these two people that I know.” He was the engineer for the Christo projects. We realized these were not artists who used paintbrush and canvas. Their work was not only in what they were doing, but in the response to it. Process is the key to what they did, and so it was a natural for us.

The other natural for you would have been Truman Capote, because what he was doing in the non-fiction novel is what you were doing in the documentary.

He claimed to invent the non-fiction novel, and in Salesman we invented the non-fiction feature. It is interesting that you bring Capote up, because after we had finished the film my brother was having lunch with Joe Fox, his editor at Random House, and my brother mentioned our desire to do a feature documentary. Fox suggested doing door-to-door salesmen, so that’s where the idea came from. I tell you, it’s all luck. I should make a film about coincidences.

How important to you were questions of composition and beauty? Were you training your eye to make the best picture possible when you were looking through the lens?

Well, there’s beauty in truth.

That’s Keats. So it’s the “Ode on a Grecian Film?”

Yes. Jeanne-Claude and Christo always insisted— especially Jeanne-Claude—that the works are temporary, so I used to quote John Keats back to them and say, “A thing of beauty is a joy forever.” Even though it is temporary, it lingers on.

Albert Maysles, David Maysles, Susan Froemke, Charlotte Zwerin, Horowitz Plays Mozart, 1987, 16-mm film, colour, 50 minutes.

You’ve been at it now for almost six decades. What keeps you going?

The next film. It’s wonderful to do something that has such an enormous reach. Millions of people have seen our films and they continue to see them. We don’t make films about war or sex. Today there is so much violence and conflict, and Hollywood’s idea is that it’s not a film unless there’s conflict. For us, a great deal of love goes into what we do. We had parents who were very loving to one another and to us. My mother told me that when she was engaged to my father they would meet for lunch every day on this street corner in Boston, and what my mother didn’t know is that my father would arrive early and place himself across the street, behind the window, so that he could look at her for five minutes. Then he would walk over to where she was.

You describe film as an act of friendship.

I think it’s pretty easy to see that. How do you get to be friends? You get to know each other. ❚