Denyse Thomasos

Denyse Thomasos (1964–2012), the late Trinidadian Canadian artist, is experiencing a steady run of posthumous success. In 2021, her work had a solo exhibition at the McMichael Gallery in Ontario. Then, in 2022, two of her paintings were included in the Whitney Biennial, highlighting two central motifs well represented in this Art Gallery of Ontario exhibition: prisons and slave boats. This exhibition, “Just Beyond,” subsequently touring to the Remai Modern, is Thomasos’s first career retrospective. It traces the trajectory of her varied, yet cohesive oeuvre, notably the application of minimalist grids and basic architectural forms to allude to slavery and the prison– industrial complex, in her early work, and to convey the raw energy and speed of the urban landscape, in her later work. Thomasos’s large-scale paintings shift between politics and formal abstraction, an admixture that stands out in this era of identitarian figuration.

The retrospective begins early, including undergraduate student work—for instance, Untitled (Self- Portrait), 1984–85, painted during Thomasos’s years at the University of Toronto Mississauga. A typical academic self-portrait study, it contributes little to a further understanding of her mature work. In Toronto at the time, few exhibitions and fewer commercial opportunities existed for painters, especially women, who were sometimes met with critical hostility from a community prioritizing video and installation art. Thomasos left Canada to pursue a painting career, beginning this journey in graduate school at Yale and then establishing herself in New York and teaching at nearby Rutgers.

Denyse Thomasos, Dos Amigos (Slave Boat), 1993, acrylic on canvas, 274.3 × 426.7 centimetres. Collection of Cadillac Fairview. Artworks © The Estate of Denyse Thomasos and Olga Korper

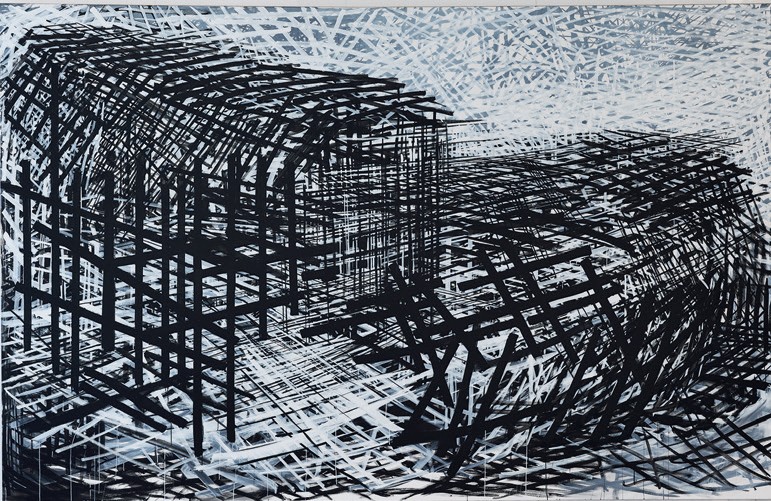

She gained prominence in the 1990s, producing her best work, which she exhibited in the United States, Canada and elsewhere, and which established the two common themes in her work. For example, two large, grid-formulated, predominantly black and white paintings are Dos Amigos (Slave Boat), 1993, and Virtual Incarceration, 1999, featuring energetic, at times angry, sharp lines that she compared to a “lash.” Dramatic diagonals project to the viewer from tightly woven grid-like structures whose rough forms subtly allude to boats and prisons.

The grid is integral to Thomasos’s work from this decade, and its inclusion straddles the formal and the political. Rosalind Krauss, in her 1979 article in October titled “Grids,” interpreted the grid formally, noting that this composition, by implication, extends outward, situating an artwork as a small part of a much larger, if not infinite, space. Thomasos’s powerful linework does extend outward, and this does imply that prisons and slavery expand to the infinite, but its outwardness, notably the lines opening near the edges of the canvas, simultaneously instills hope in a world existing beyond the confinement they delineate. Interestingly, the independent critic Margarita Tupitsyn observed that in Russia, unlike in the West, the grid’s historic place in modernism was as much political as it was formalist. Thomasos likewise used the grid to explore confinement and imprisonment, to politically engage the viewer in the trauma of the transatlantic slave trade and analogize it to the prison–industrial complex and its disproportionately high Black incarceration rates. In her best work, Thomasos combines Krauss’s formalism and Tupitsyn’s political signification, creating a bristling, unresolved tension between form and concept and hope and oppression.

However, other grid paintings cohere around a concurrent formalism freed of all but the most abstract architectural references. Representative of this approach is Rally, 1994, in which she arranged loosely rendered, horizontal, bright, sometimes luminous coloured bars into squares to form a grid configuration. The narrower horizontal lines between the bars appear architectural, recalling windows in dense apartment blocks, foreshadowing the semi-representational architectural turn her work would soon take. This work also indicated a shift to an emphasis more formalist than political.

Installation view, “Denyse Thomasos: Just Beyond,” Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, 2023. Photo: © AGO. Artworks © The Estate of Denyse Thomasos and Olga Korper Gallery.

Then, in the 1990s, Thomasos abandoned her definitive grids. Her work from the aughts, such as Excavations: Jaisalmer Night Suspension, 2007, instead focused on abstracted container-like forms, both urban and architectural, and was informed by the artist’s travels throughout Asia. At points, the more rigid lines recall the deliberate technical lines of architectural drafting, especially when paired with looser, more abstract patches and gestural colour strokes.

The late work, found in her studio after her death, was abandoning imagism, focusing less consciously on line. Untitled, 2012, is characteristically more abstract and expressionistic—the paint applied gesturally and fluidly with vertical drips below the central form. Again, the loose imagistic references are architectural and urban but are now defined by loose colour blocks and curvy brush strokes. The architectural traces are still there but are minimal, with colour pushing them to the background.

Denyse Thomasos’s later work leaves questions about what she prioritized overall—an expressionist formalism or an identity politics rooted in the 1990s. One wonders if she would have revisited identity politics had she lived to witness this post-George Floyd era. ❚

“Denyse Thomasos: Just Beyond” was exhibited at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, from October 5, 2022, to February 20, 2023.

Earl Miller is an independent art writer residing in Toronto.