Dark Enlightenment

An Interview with David Lynch

David Lynch, a painting student in 1967 at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia, was working on an all-black painting of a night garden when he sensed that a wind, mysteriously generated from within the canvas, stirred the leaves he had just rendered. The direction this apprehension would suggest to him is now history: David Lynch the painter became David Lynch the filmmaker. But like all stories, this narrative is not so tidily packaged. The truth is, Lynch never stopped painting and drawing, and he has since added still photography and music to the art forms that compel his interest. But in his varied production as an artist, he has painted for a longer period of time than he has done anything else. He admits that finding his voice as a painter has been “a total struggle. For me, the grand experiment has been to keep chasing the thing I haven’t found.”

What he has found is a way of presenting what he calls humanity’s “deep darkness” in unique and unmistakably Lynchian ways. The startling intensities of his films, their sense of engaging us in a lived-in, visceral experience, are undeniable. His film history is a nightmare from which we want to awaken, then we’re not so sure, and we change our minds. His work has about it a distinct quality of menace and danger, while at the same time it can be comic and endearingly preposterous.

David Lynch, I Was a Teenage Insect 2018, mixed media painting, 66 x 66 inches. Images courtesy the artist and Kayne Griffin Corcoran, Los Angeles.

There is something inexplicably innocent about Lynch’s approach to art making. He has said the mind “is a big beautiful place, but it is also pitch-dark.” His various art practices move in the direction of that beautiful pitch-darkness. He makes what his imagination wants to see, and the nature and tone of that making seem unaffected by any sense of recognized transgression. When asked whether his motivation matters in assigning meaning to a work, he is adamant in his denial. “Not one little bit. I always say in cinema that I need to know what it means to me, but I know full well that there are millions of interpretations for the work.”

His films and paintings, then, are not him; they are merely made by him. It would be incorrect to assume that they are also mirrorly made. They contain ideas, attitudes and characters, but they are not reflections or traces of his own psychological trauma. “Things end up in painting or in cinema because they’re in the world,” he says by way of explanation, “but the artist doesn’t have to suffer to show suffering.” What is no less startling than the darkness of his films is the lightness of his world view, a perspective he attributes to his 45-year-long involvement with mantric Transcendental Meditation. It is a surprise to discover that in conversation he is completely unlike his films and paintings. He is a pure example of an unfettered imagination.

During the interview I asked him about an oil and mixed media painting called Bob Loves Sally Until She Is Blue in the Face from 2000. Written on the roughed-up surface of the canvas are the words “Oh yes,” the kind of rote encouragement that turns up in every porn film. But Bob is out of place; he seems to be a character imported from a shunga central casting studio. I read the painting in the same way I looked at a lithograph like I Hold You Tight, 2009, where a man’s long arms end in fingers that seem to be strangling his naked girlfriend more than romancing her; or in Pete Goes to His Girlfriend’s House, 2009, where Pete holds a gun in one hand and a knife in the other. It’s a visitation devoutly to be avoided.

I asked Lynch whether Bob and Sally’s amorous encounter was one of his Janus works, an image that looks simultaneously in opposite directions. Being made love to until you’re blue in the face could be about extreme passion or as easily describe the effect of murderous violence. The work could be seen as a kind of comic snuff painting. David seemed surprised at my question and his response spoke to a guileless phenomenology. “See, there’s that beholder again,” he said. “It’s just what you see.”

The following telephone interview was conducted on June 28, 2018, in Los Angeles. David Lynch’s one-person exhibition will run at Kayne Griffin Corcoran in Los Angeles from September 7 to November 11, 2018; and a major survey show of his work in all media, called “Someone is in my House,” will be on exhibition at the Bonnefantenmuseum in Maastricht from November 30, 2018, to April 28, 2019.

BORDER CROSSINGS: The story about the moving painting is well known and has a Paul on the Road to Damascus conversion quality about it. Is there an equivalent story about your devotion to painting, which, in some ways, you’ve stayed with longer than filmmaking?

David Lynch: There is. I was always drawing when I was little and did some painting and loved it, but I never thought of it as something an adult would do. In my eighth grade our family moved to Virginia and I started high school there. I was over at my girlfriend’s house one evening and I went outside into her front yard. Some people had come over and one of them was named Toby Keeler. He went to a private school, so I was meeting him for the first time, and we got talking and he told me his father was a painter. At first I thought he was a house painter, but he said, “No, no, a fine art painter.” And a bomb went off in my brain. It was like I was one way before he said that and I was completely different after he said it. I just thought, that’s what I want to do. All I wanted was to be a painter. And it went like that. It led quite quickly to this thing of dedicating my life to painting and the art life. It was the most freeing thing—you smoke cigarettes, you drink coffee and you paint.

That’s where Robert Henri’s book The Art Spirit comes in?

Yes. You get deeper and deeper and deeper into it; you find your way and your own voice. It has been a total struggle. So many painters find a way, but for me the grand experiment has been to keep chasing the thing I haven’t found. It has to do with organic phenomena, with paint and sculpture flowing together and with ideas in that world. But this world of painting is the best. It’s fantastic, and that talk many years ago in the front yard opened the door. I knew it once Toby said it.

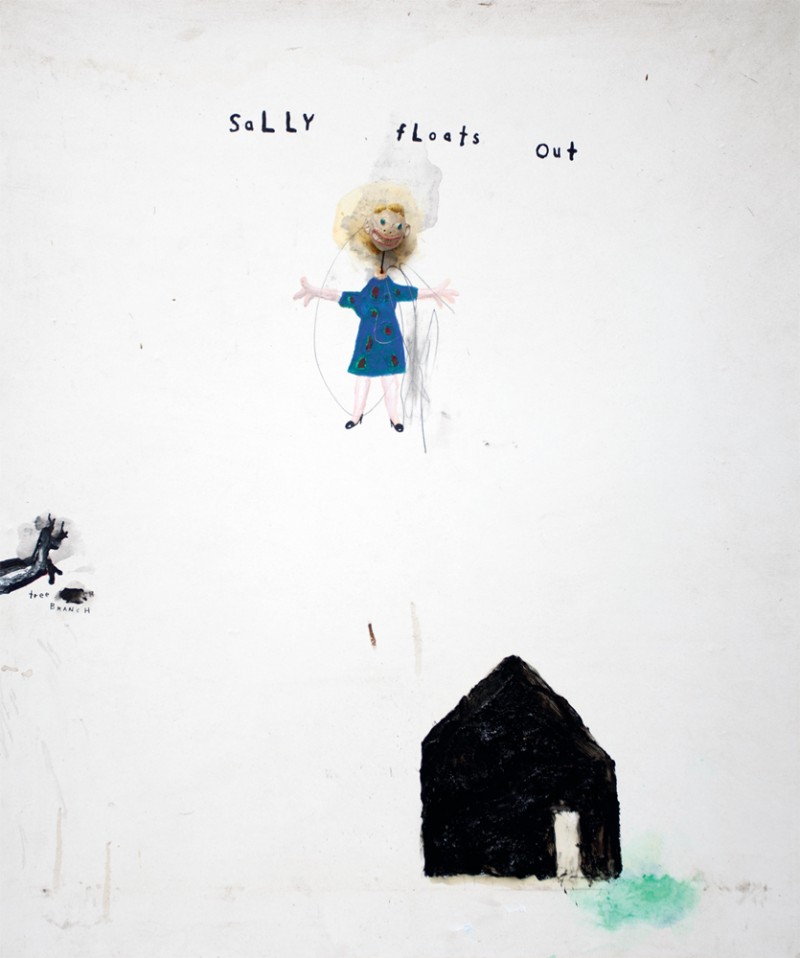

Sally Floats Out, 2018, mixed media painting, 31 xx 27 inches.

The first drawing reproduced in the large Steidl book of works on paper is a written piece that says, “I love to draw and I’ve been drawing off and on since I was real little.” You reverse the “d” on “drawing” and then sign it “David” the way a child would.

Yes, this childlike thing is one of the keys, this freedom in not having a bunch of intellectual stuff blocking the flow. I like crude, childlike, organic things. Nature plays a part, and it’s hard to say in words, but it’s a feeling that involves paint and textures and juxtaposition of shapes. It’s not intellectual and it involves bad painting and bad mistakes, which are so beautiful once you get into them. We have so many uptight things in us that it’s really important to break it all down and get into that fantastic, childlike world.

Watching you making a painting in The Art Life, the 2017 documentary, is fascinating because what’s evident is your process in trying things out to see if they work. It’s almost as if you construct the painting more than you paint it. You put it together.

A lot of it is that way, and then I have to be able to suddenly destroy something to find that next thing. A lot of times out of destruction you find something that is really organic and beautiful.

At one point you’re trying to put a word up in the upper left corner of a canvas and you finally say “motherfucker” because you can’t get the drill to make the hole you want. It looks as if you’re not as good a carpenter as I know you are, because you can build everything from sheds to houses.

Well, that’s the thing. I love carpentry and I so respect great carpenters. But in the world of painting, bad carpentry is what’s more pleasing.

I’m impressed by how many art forms you work with. How do you know which one—from film to painting to photography to lithography—is the best vehicle for the idea or the image that you want to get across?

That’s a good question. I think the idea tells you that. I have this theory that every medium talks to you. You have a dialogue and you understand it by getting to know it. So with lithography you do this and this and this and it looks like that. You get the hang of it; you get the dialogue going, you know what it’s going to do. It’s a lithography way to realize those ideas. So there are ideas for lithography, there are ideas for painting, for cinema, there are ideas for furniture. These ideas tell you which medium to choose and what to do once you’ve made that choice.

When talking about Mulholland Drive, you said that you don’t set out to do a certain thing but that the ideas tell you what the film’s going to be. I assume something similar happens in painting— the act of painting is to follow what the idea behind the painting is telling you.

In a film all these things happen mostly in the script form. It’s not like you just pour it out. It’s a lot of action and reaction to get it to feel correct in the script form. And if it feels correct there, that’s your guide for filming. In painting I always say you just need an idea to get you out of the chair. Then it’s a process of action and reaction; you do what you thought the idea was telling you and you can like it or not, but it gives you another idea. It’s always a process of acting and reacting until the thing is finished.

Writers will say that at a certain point in writing a novel, a character will take over the story. They’re almost not in control anymore. Does that also happen when you’re making a painting, when the process is taking over rather than your directing it?

It’s not that the process is taking over; the ideas are taking over—always the ideas are guiding the boat. I say we don’t do anything without an idea. It comes to a point where you say, “Oh my goodness, this is it,” where the idea is so strong that you just complete it.

Have you deliberately kept your visual art practice separate from your filmmaking activity? Have you been careful to keep them discrete?

Absolutely. All the time I was painting, there was this attitude that Sunday painters are hobby painting. It was so much bullshit. I always think of painting and I have always painted in between films. But I was known for filmmaking and you’re not supposed to be doing other things. Now, that’s all changed and people are into different media. They always were but now you’re given permission to do them. It’s a better world.

Installation view, “David Lynch: Naming,” 2013, Kayne Griffin Corcoran.

Do you have a sense that your various art practices have been cross-generative? Does one feed the other?

Sometimes, but it’s pretty separate. We all have our likes and dislikes. There are millions of ideas out there and you’re going to fall in love with certain ones and someone else will fall in love with other ones. We’re looking for those ideas that we can fall in love with, and some of them are cinema ideas and some of them are painting ideas.

I can see evidence of your admiration for Francis Bacon and the way that certain figures get distorted in Lost Highway, and in some of your lithographs the figures in bed have a Baconish quality.

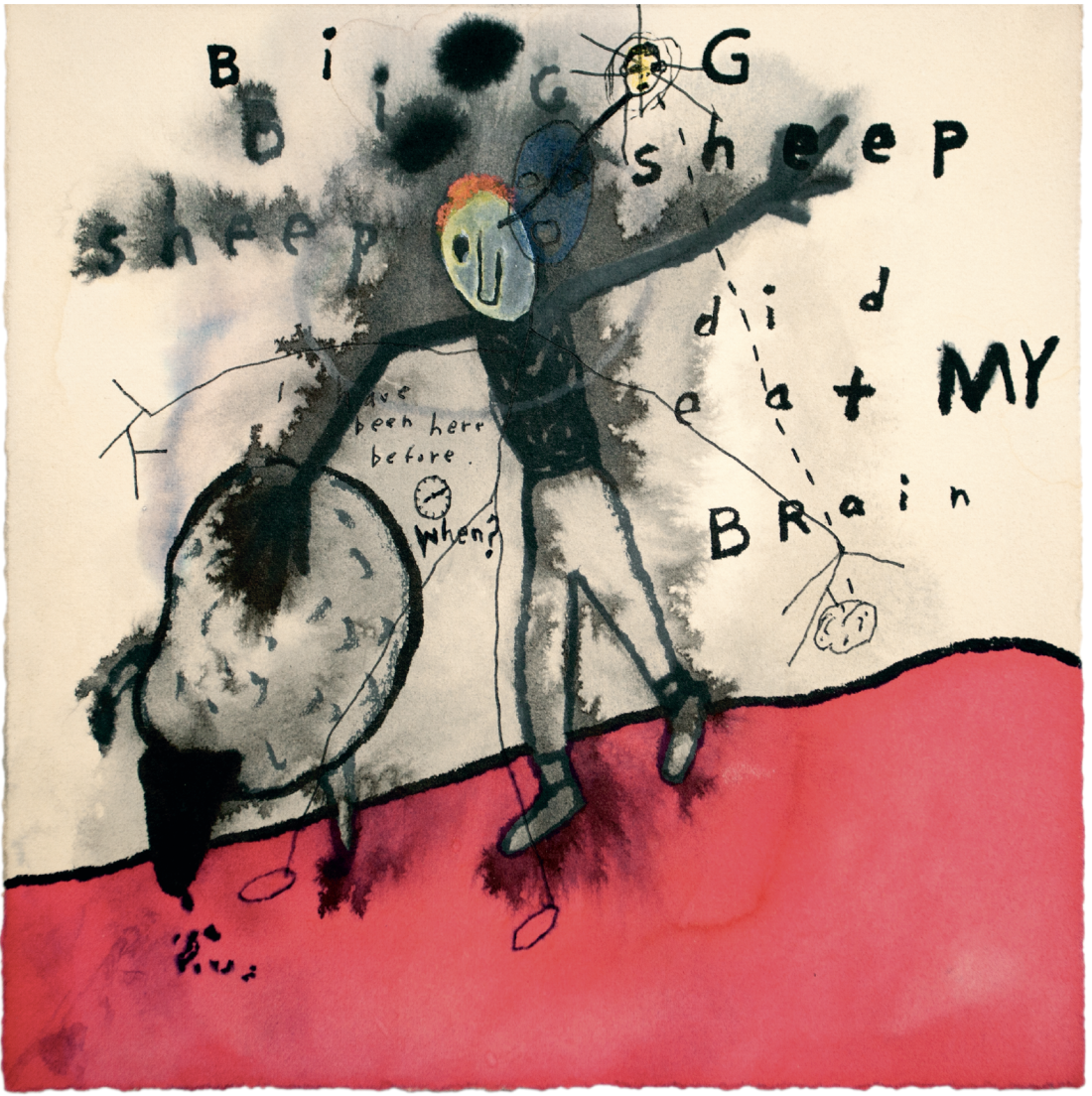

I love Bacon. He’s a huge influence and his distortion of the human figure is so important. I like childlike distortion as well, which I call “bad painting.” It’s like the Blues. It seems really simple but in its simplicity it’s hard to get that true feel. There’s a certain way that childlike things get distorted. It’s really, really difficult to get it to feel right but it is possible.

One of the things that struck me about a lot of your paintings is they imply a simple narrative. A man, a woman, an insect or a dog will interact with one another doing simple things, like an insect bites a woman.

Yes. I did a series of photographs called “Small Stories.” Bacon said he hated stories; he didn’t want any story, but I like a story in the painting and I like the words to go with the painting. I like the way words give it the texture of letters.

One of the compelling and explosive things about your work is the way you use text and letters. Was that with you from the beginning?

Not in the beginning. The first thing was more three-dimensional stuff. In the ’60s I would glue things onto the painting and then in the ’80s I started rubber-stamping little letters onto artist’s paper and cutting them out. They reminded me of little teeth and I would put them on to the edge of the painting and into the title.

So the words are written; they’re not found.

No. I stamp them. I made many, many As, many Bs, and then I’d use them to perform the words.

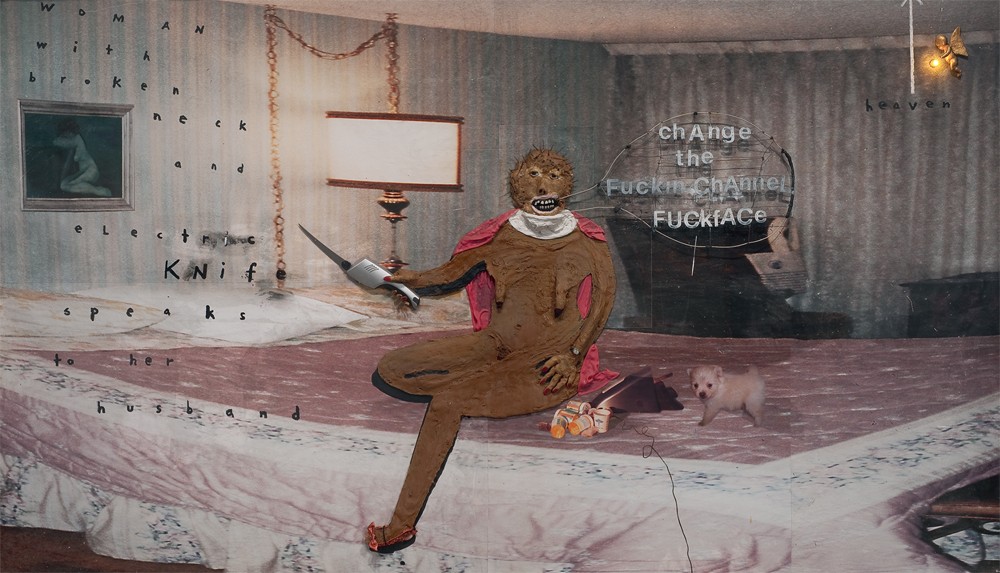

Your language fragments often carry a story that precedes and also anticipates what could develop out of the scenario we’re looking at, like in Pete Goes to His Girlfriend’s House (2009), Change the Fuckin’ Channel Fuckface (2008–09) or I Burn Pinecone and Throw in Your House (2009). There are such rich implications in the things these characters say. Is there a built-in narrative in these paintings that takes us beyond and outside the frame of our looking?

I always say every viewer who goes up to a painting creates a circle; the painting goes into the person and they react in a certain way, depending on how they are because on the surface we’re all different, and then it goes back into the painting. They get this dialogue going and the viewer walks away with a certain thing and the next person might walk away with another thing. It’s so beautiful how that thing can talk to us.

Is the painting telling you something specific that might be different from the way that I would view any particular painting? Does your motivation in making the work matter?

Not one little bit. I always say in cinema that I need to know what it means to me, but I know full well that there are millions of interpretations for the work. And every interpretation, every person’s take, is valid. At a screening in a big theatre filled with people, all the frames of the film are exactly the same, the film is the same length, the sound is the same, but everybody’s going to get something a little bit different. And the more abstract the film is, the more differences that are going to pop out. Then when the next audience comes in, it could be a whole different feeling, depending on the people there. It’s always the person and the work, and you just don’t know what goes on in people’s heads and hearts when they see it.

Change the Fuckin’ Channel Fuckface, 2008–09, mixed media on canvas, 72 x 120 inches

You don’t storyboard your films, do you?

Sometimes on certain sequences-if it’s a big special effects thing. Everybody has to know exactly what’s going on to build it and make it work. But the storyboard is mostly in the head.

I was interested to see that there were the very detailed drawings for Eraserhead that you did in 1970. They’re not simple sketches.

We shot Eraserhead at night; it took a long time, and the lighting was very particular. So half of the time I would be drawing. I didn’t have money for painting then, but I had time to draw. One time I drew this little woman and I liked her when I looked at her. My first thought was, “Oh, she lives in ‘a’ radiator.” Then I started thinking more, and I realized that she lives in “the” radiator. And I went running into the set of Henry’s room and looked at the radiator, which I had purchased from a studio that was going out of business. And this radiator was unique, I don’t think I’ve ever seen one like it, and it had a perfect little place for this lady. That came out of a drawing I did while waiting for lighting and it led to a whole thing that absolutely had to be in the film. I always say something isn’t finished until it’s finished; ideas can come along during and even after you think the script is finished. So you stay on guard.

Boris Groys, the art critic, says that your painting allows you to run more risks than you do in film, that painting is really the dark art form. Is that a notion you subscribe to?

I don’t know. You have a lot of freedom in both media. I started in painting and it led to film, and I have always said that it’s totally ridiculous and a crime that a filmmaker doesn’t have final cut. Because that’s the way it is in painting. If you don’t have that control, the film is not yours anymore and what happens is, you’ll just die. You’ll die.

You’ve talked about the magic of blackness and the idea of people coming out of the darkness, because when you’re lost in the black, a different kind of story can emerge. Does it give you more freedom? It seems that the blackness is the place where freedom can best insinuate and manifest itself.

In a way, you’re right. It’s connected to this idea of the un-manifest and the manifest. I’ve been practising Transcendental Meditation for almost 45 years now, and Maharishi brought out tremendous life-saving, life-bettering knowledge. He says that infinite silence and infinite dynamism are together within all of us. This infinite silence is un-manifest, it’s no thing, and yet it’s hand in hand with infinite dynamism. And they’re absolutely together in that field. So it’s this unbelievable, powerful and almost electric balance. It’s like the deep darkness and it’s infinite; it’s just silence and yet it holds this infinite dynamism. That’s the way the darkness could be. And another thing is, in life, we’re all sparks off the divine flame, and we’ve gone out into the void, into these different worlds, and gotten lost. So we’re lost in darkness and confusion, like Henry Spencer in Eraserhead, and we have to find our way home. So coming out of darkness is a cosmic thing of finding your way home.

One thing that is also made manifest in your work is a repeated sense of menace.

And a fear of the unknown.

Is that because we’re afraid of not knowing what it is, or is it terrifying because we know exactly what it is?

Could be both. The field within is all-positive, and you can’t lose with that. Our home is infinite bliss and it’s the most beautiful thing. But in the world in which we’re lost, there are so many things that can get us-there are monsters and much negativity. But we have free will; we make choices. There’s a law of nature: what you sow is what you reap. There’s no escape. It’s set. So anything we do to anyone else, we are in effect doing exactly the same thing to ourself. It’s something to think about.

That’s interesting because you have a watercolour done in 2011 called My Shadow Is a Monster. You realize that the duality is inside us; it’s not outside of us.

Exactly. And when you transcend and experience that field within, you’re expanding all those positive qualities of consciousness, and the side effect is to lift away that negativity. That monster inside is dissolving and all the impurities are lifting away. The beauty is it’s like gold coming in and garbage going out.

Pete Goes to His Girlfriend’s House, 2009, mixed media on cardboard, 82 x 130 inches.

In a work like Do You Want to Know What I Really Think from 2003, a man is standing in a room holding a knife and a woman has been asked to undress. And her answer to the eponymous question is, “No, I don’t want to know what you really think,” because she knows that it’s not going to go well for her.

Exactly. There is so much stress in the world and we can only imagine the kind of domestic violence that goes on in houses across the land. That’s what that painting is about.

It’s interesting how often the word “house” appears, not just as a written sign, but you paint and draw houses a lot. Is that a more personal expression of what “house” and “home” can mean, and how one can interpret both the darkness and the lightness within that particular domicile?

Absolutely. I love houses, I love the idea of inside and out. It’s just as you said: it could be horror in there, or it could be really nice.

There’s a lovely 1990 oil and mixed media called Here I Am, Me as a House, and in Suddenly My House Became a Tree of Sores, you return to the same subject. I gather that you want the house to be a vehicle that can express the range of our essential humanity on both the good and the bad sides. Is that how it works?

Yes. Suddenly my house became a tree of sores. You know, everybody’s got this thing where everything changes because they find something in the house.

One of the other words that appears most often and of course it comes up in your memoir, Room to Dream-is the idea of dreaming. Why has the dream played such a significant role in your visual art practice?

I have gotten ideas from dreams but not so many, They seem to come from being awake. But I do love dream logic. It’s this thing that’s so hard to say in words but you intuitively know it, Like, you know something in an instant in a dream and while it’s completely known and completely real, it doesn’t make any sense when you tell it to your friend the next day. You can say those kinds of things in the language of cinema, and you can also say certain things like that in painting.

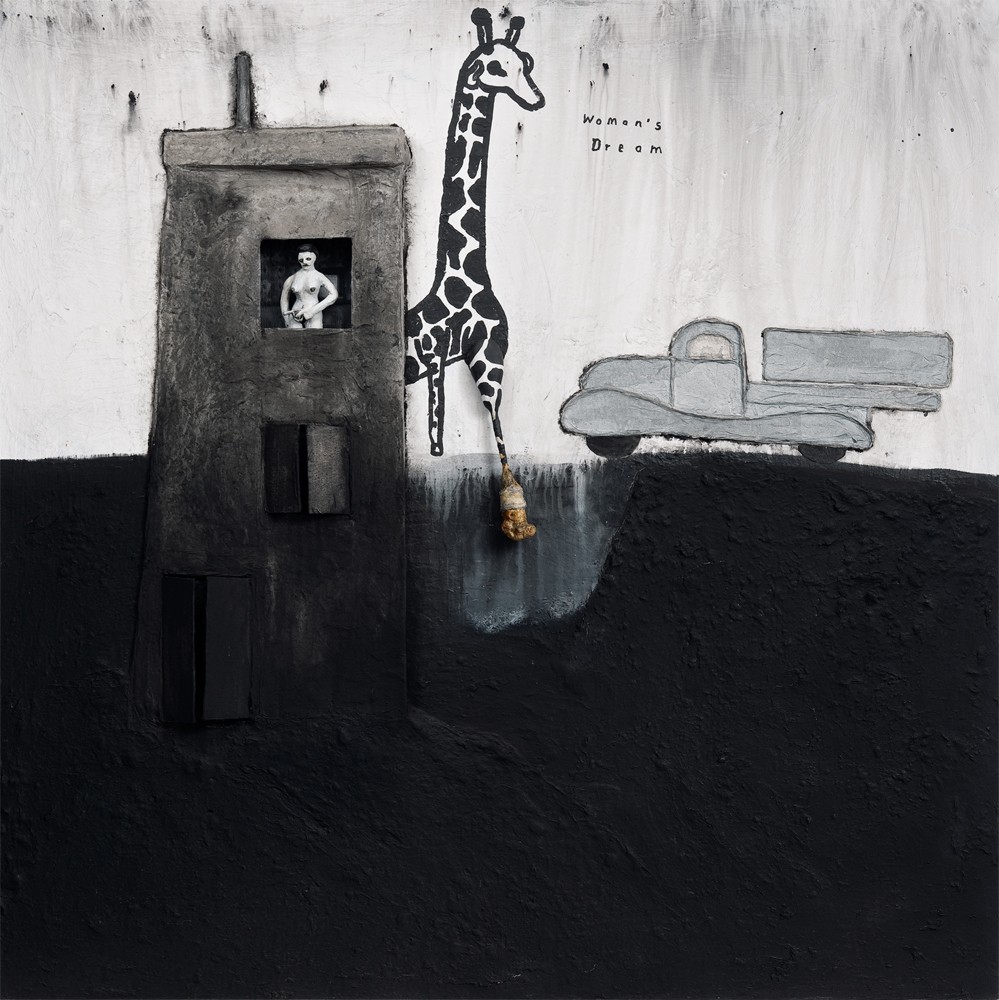

Your characters have dreams that are pretty various. Woman’s Dream (2013) involves a giraffe, whereas the Fisherman’s Dream includes a steam iron. I just can’t figure out …

What the deal is? It has to do with what would feel good and what would conjure thoughts that couldn’t happen in any other way. Sometimes I get a fixation on two things in one, so there would be one thing and it would be a certain way, and then I have to decide what would feel correct with that thing there. It turns out there are not that many things.

I keep thinking that your work operates out of what the surrealists would call “automatic composition,” that the idea comes to you and then that idea begins to generate other possibilities.

It happens in all of them, in a way. They start one way and then through this process of action and reaction, they become a little bit different, sometimes very different.

You have a small watercolour-it’s only 4 by 6 inches-called Is It True? And what we see is 2 + 2 = 4, and then the written title question. It makes me think that knowledge is something that has to be questioned, so that if one were to place you philosophically, your epistemology would be one of doubt, mistrust and constant questioning. Do you think that’s fair?

Yes. I always say everybody is like a detective and there are clues in the world. We hear and see and feel things and then we start thinking about them as a detective. We ask ourselves, “Is that true? Does that make sense? Is this thing false?” That’s why, in going through life, I think intuition is super-important. And to figure out what’s true for you by seeing these clues and questioning the things inside.

Woman’s Dream, 2013, oil and mixed media on canvas, 71 x 71 inches.

So Kyle Maclachlan’s character in Blue Velvet becomes an inadvertent detective who has to figure things out. As do many of your film characters.

Yes. It started, I guess, in Eraserhead, and they’re all trying to figure something out.

Do the answers come as full answers or do they come as additional kinds of questions? I’m trying to get at the notion of what do we finally conclude out of the human enterprise. What can we come up with as an answer that’s satisfying?

That’s the thing. In detective novels very rarely is solving the crime satisfactory. You say, “Oh, okay, it was that.” It’s like learning a magic act; you learn what they do and it’s a letdown. In the field of relativity you think many things are going to make you happy and give you that feeling of satisfaction, but in reality the only thing that is going to give you this fantastic feeling of completeness is gaining your full potential and enlightenment. And you unfold it by experiencing that infinite field within. It’s all there and it is completely satisfying and euphoric. You just need to bring it out for yourself.

You said that one of the reasons why you took on directing Dune was because the character in the novel, Paul, is searching for a kind of enlightenment, and that his pursuit was one with which you could have some sympathy.

Yes, the sleeper must awaken.

The writer who comes to mind when we talk about the sleeper awakening is William Blake. In Songs of Innocence and Experience he has this notion that you go through experience, and out of it you come to a heightened innocence. It’s not dialectical; it’s a continuous process leading to knowledge.

I heard that he was probably enlightened. But with this thing of heightened awareness-if you put the word “infinite” in front of “awareness,” that’s infinite consciousness, that’s infinite enlightenment. It’s not just knowledge; it’s knowledge and experience. Knowledge validates experience, and you start expanding consciousness; it leads to higher states and ultimately to the highest state, which is called “unity” consciousness, and you’re home free. It might be a long way down the road, but with every step as you go towards light, things get brighter and better.

Have you become more enlightened as you’ve gotten older?

I don’t know. I’ve become happier, and I really believe that the more you transcend through every day, life becomes more like a game than a torment.

You have remarked that contrast is what makes things work. Do you have to find a way to orchestrate that contrast in your painting or is it naturally there, which means making a work of art is simply following the contrast that is in the world rather than your using it as a compositional strategy to make a painting?

There’s no strategy like that because it’s not an intellectual thing. It comes with the idea and it’s the idea that starts you, and then it’s this process of action and reaction. This is the thing you hope to keep alive. And there’s got to be a freedom to say, that didn’t work, it’s got to go. Then in the process of destruction, a beautiful new thing can emerge. It doesn’t always emerge; sometimes you can be helped by accidents-it’s a little bit like the random things the surrealists did. Those things are tools and I think they’re super-important. Random things, random choices and thenbang, an idea comes.

The idea of randomness is complicated. Ginsberg said that mind is shapely, and what he was getting at was that the mind finds pattern and form, with the result that whatever we end up doing will finally assume some form, rather than formlessness.

I think that’s absolutely right. Formlessness is in that transcendence. It’s the ultimate abstraction. In the field of relativity everything has got a border; everything’s got a form. There’s nothing really formless except what’s inside.

Big Sheep Did Eat My Brain, no date, work on paper, 8 x 8 inches.

When you say “inside,” I’m reminded that one of your constant visual tropes-it comes up a lot in the lithography-is the idea of the stage. You have fire on stage and an angel on stage. You actually present your small stories inside a proscenium frame. Was that a conscious device?

Absolutely. I just love the stage with curtains and a rectangle or a square. It’s a defined space. When you run a film in some theatres, they have curtains on the side and an arch, and they’re beautiful things that set a frame for your work.

The stage is the arena of the watcher and the watched. That’s perfect Lynch territory, isn’t it?

Yeah, yeah. It’s like the audience is out there and then there’s the thing happening on the stage. It’s the same with cinema. Even though there are real people on the stage, it’s different but the same.

One of the most beautiful of your lithographs is called Angel on Stage, in which this transcendent winged being lights up the darkened space. Why did you make that image?

I don’t know. I got an idea to do it. But the beautiful news is, no matter how dark the night has been, as soon as the light comes, the darkness goes. Maharishi always said, don’t fight the darkness-meaning negativity-don’t even worry about it. Simply turn on the light. The light he’s talking about is the light from that field within, the field of unbounded consciousness and creativity, happiness, love, energy, peace. You have it all.

This last response embodies the dilemma you present for viewers of your films and your visual art as well. It looks a lot like a dark world. Even the palette of your visual art tends to be a little bit on the dark side. But you’re not like your work.

Right. It’s really weird but in the newer work I’ve been working on white backgrounds. That seems to be where it’s going.

Is there a hidden meaning emerging?

I don’t think so; I just like it right now. I don’t know if it means anything. I sometimes think, what if I suddenly turned it all dark? But it doesn’t feel right. There’s a bunch of things involved. I’m fascinated by the world and I love absurdity and a lot of things people do are really dark. It’s unfortunate that people make bad choices and get into trouble. Looked at one way, it’s absurd and even somewhat comical. But looked at another way, it’s sad and horrible. So those things end up in painting or in cinema because they’re in the world. But the artist doesn’t have to suffer to show suffering. You can be very, very happy in your work and still show suffering. It becomes part of the story but it doesn’t mean the whole film is dark. It means that something’s going on. There could be very light things swimming in with the darkness and together they make a story.

I notice that your outdoor studio has a large reproduction of Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights pinned on a wall.

Yes, I pinned it up there. I went to see the actual painting, which has been restored, and it’s unbelievably beautiful. And the packaging is unbelievable carpentry. It’s built in a thing with hinges. No reproduction has ever done it justice.

You start doing photography around the time of The Elephant Man in 1980. What got you interested in the medium at that time?

I must have gotten some money because I always wanted to take pictures. I got a brand-new Canon camera just before I went to London for The Elephant Man. I’ve always loved cities and abandoned factories and railroad yards, and I’ve always loved nude women, and those are mainly what I’ve been photographing. What actual celluloid film does with those things is different from digital. You can still get the feel in digital, but black and white film is really beautiful for factories and nudes.

You’re the only artist I know who’s been able to combine the factory and the nude, which you did in a lithograph from 2007 called Factory at Night with Nude.

I like that one a lot. There are unreal textures in abandoned factories, where the most beautiful things are happening. It’s like going to the best place.

Man with Potato, 2015, mixed media painting, 24 x 24 inches.

One of the intriguing things about your nudes is that the viewer often doesn’t know which part of the body is being looked at. Do you want that topographical confusion?

I don’t want to confuse anybody, but I want parts of things, parts of factories. I don’t like going wide and seeing the factory sitting there. I prefer to go in and get more details, and they turn into abstractions. And the female form is filled with possibilities for unreal abstractions.

You’ve said that you like to see life in extreme close-up. In a sense your photography has amplified that perceptual quest.

That really is true. These close-ups are the thing.

Where did the distorted nudes come from?

It was the first thing I ever did with Photoshop. I got hold of this book called A Thousand Nudes. They’re anonymous photographs put together by a German man. I wrote to him and got permission to do a book. I would take those images, undo them and then put them back together in different ways; I loved distorting those pictures. I just went into heaven working on them.

When I saw them I thought of a range of photographers including Hans Bellmer, Pierre Molinier and even Joel-Peter Witkin.

Yes, I love Joel-Peter Witkin’s work. To me, he’s as much a painter as a photographer.

I’m interested in the way that scale and perception operate in your art. You have said that you don’t want to be anywhere that was not your world, and that what you loved about doing Eraserhead was that it was a world “in your own little place where you could build everything and get it exactly the way you wanted for hardly any money-it just took time, it was just so beautiful, everything about it.” Are you still creating your own world in circumscribed spaces that open up imaginatively?

Yes, if doing a painting is creating a world and if making a film is creating a world. The only difference is-and it’s sad-money forces us to go more quickly in film. On Eraserhead I could live in that world and imagine all the things surrounding it because I lacked money. It was beautiful and really important to live in that world and let it seep into you and think about things that could lead to way more ideas for that world. It’s gone now because of speed.

Nobody gives you that time anymore?

No way. It’s impossible. The set goes up, you go in, you shoot. And then the next day the set’s gone. It’s sort of a horror. But for those moments it’s totally real, you’re in it, and you better enjoy it and feel it as deeply as you can, because it’s not going to be there for very long.

In Room to Dream you make it clear that the size of the room you need to dream in isn’t large. When you write about your childhood, you say your world wasn’t bigger than a couple of blocks, but that there were huge worlds within those two blocks and everything you needed was there.

Exactly right. Some people love to travel to see the world. I like to stay at home and have the world mostly inside. The things around you can give you a feeling and you can conjure them, but most of the things are going on inside.

You have another lithograph called A Lonely Figure Talks to Himself Softly, and what he says to himself is, “Where are you going, you fucking idiot?” That’s not you talking to yourself, is it?

Sure, sometimes. It’s unfortunate when we’re pretty lost and not really dealing with a full deck-because the full deck is enlightenment-we get confused and we sometimes make wrong choices. And it’s difficult. I think everybody is a hero; in a strange way everybody is trying to find the answer, trying to do the right thing, and trying to fulfill their desires and make it be okay. It’s just that a lot of negativity pushes in and causes people to make wrong choices. The prisons are full of people who did a wrong thing in a moment and then it’s a long time in a tiny room.

In The Air Is on Fire catalogue, Andrei Ujica is trying to explain your accomplishments in so many media and he moves towards the idea of the Renaissance artist. His description of that rare figure is a being “who already carries a complete cosmological project within himself.” That struck me as not being a bad way of talking about you and your various practices.

That’s really nice but I don’t know exactly what it means. To me, it’s simple. There are ideas and each one is infinitely deep, and you can get a dialogue going with it and go deeper and deeper in all the different media. And each one is euphoric and a real thrill.

But don’t you have to go deep inside the dark to find self?

In reality you need to transcend every day. That’s the key to everything we’re looking for. If you’re doing that every day, then you’re not afraid to go into these different worlds. You’re catching ideas and realizing those things with as much freedom as you can possibly have.