Close Stitching

The Intimate Delight of Janet Nungnik’s Textile Art

Love and happiness radiate from Janet Nungnik’s extraordinary textile art, qualities, she has said, that originate in childhood memories of her close-knit family and life on the land. Her earliest recollections, celebrated in many of her acclaimed wall hangings, were formed at a far remove from the hamlet of Baker Lake (Qamani’tuaq), where she has lived and worked for many years. Nungnik was born Ariaut Anautalik in 1954, in a small camp west of Hudson Bay, in the Kivalliq region of what is now Nunavut. Through the marriage of her parents, Martha Tiktak Anautalik and William Anautalik, she is a member of the inland-dwelling Ihalmiut and Padlermiut peoples, distinctive cultural groups within what is known collectively as the Caribou Inuit.

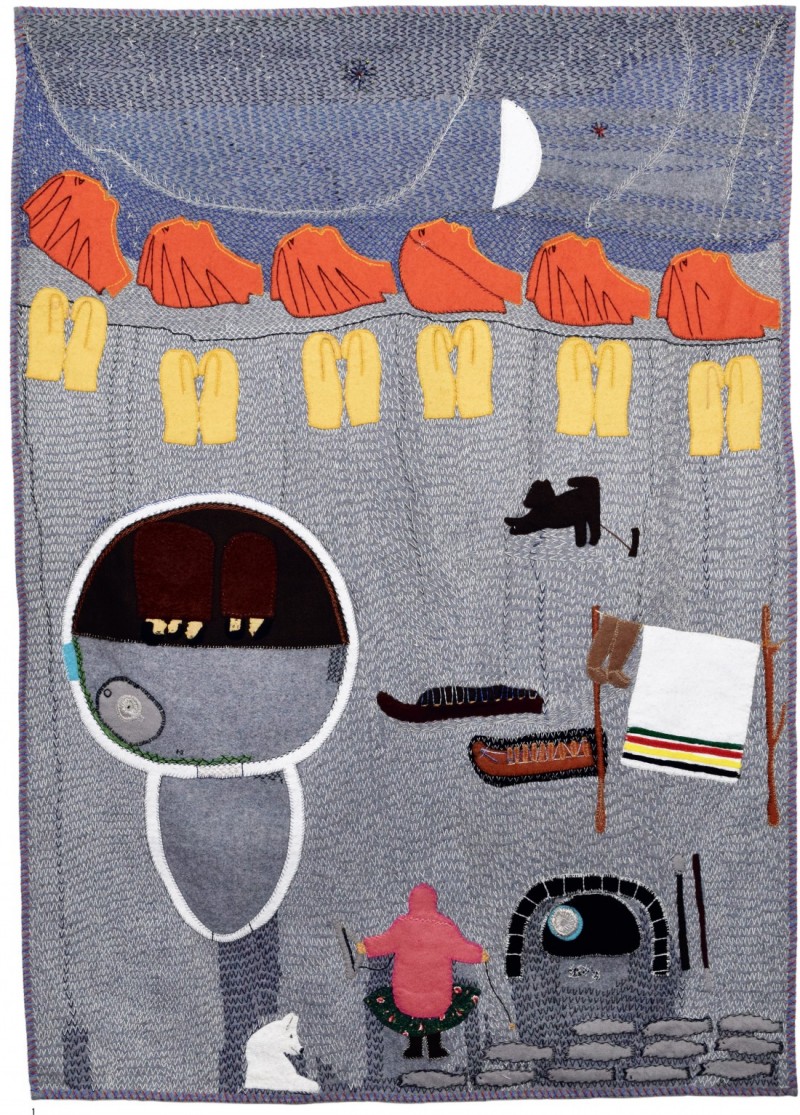

Janet Nungnit, Northern Lights (Inside the Iglu at Night), 2002, wool felt, embroidery floss and beadwork on wool duffel, 60 x 44 inches. All images courtesy Marion Scott Gallery, Vancouver.

Her art is richly narrative and includes scenes of children playing, families sleeping cosily together inside iglus, dogsled races, community dances and loved ones returning from hunting and fishing expeditions. Rainbow of Memories, 2004, situates a parka-clad figure on a dogsled in a colourful landscape populated with ookpiks and butterflies and overarched by a rainbow, a symbol of gratitude for the rain. At the bottom of this wall hanging, a young girl swims in blue water, her caribou-skin clothes and boots carefully arranged on a Hudson’s Bay blanket on the shore. As with all Nungnik’s works, the forms are crisply cut and deftly appliquéd on wool duffel, then embroidered overall with such consistency that the stitches, which include the feather, herringbone and arrowhead stitch, function as delicate washes of colour over the solid-hued passages of cloth.

Nungnik may also employ beading in her wall hangings, to represent the decorative patterning on the clothing of her depicted figures. From the 19th century forward, Inuit women used trade beads to adorn traditional clothing such as parkas, and beads have subsequently found their way into Inuit wall hangings. The transition is neatly circular: before Jessie Oonark created the first Inuit wall hanging in 1964, inaugurating a new and desirable art form in the North, the women of Baker Lake and other settlements generated income by making beaded and embroidered clothing and accessories for sale to Canadians in the South, through governmentrun arts and crafts programs.

In Vancouver last spring for the opening of her solo exhibition at the Marion Scott Gallery, Nungnik sat for a videotaped interview in front of an untitled wall hanging. Made in 2004, it depicts a scene from her childhood in which she skips rope, her brother plays with a ball and string, her mother stands beside a trout-filled body of water and fish hang on a line to dry. “I was a very happy child,” she said. “I looked after my brother Eric, we played lots, we walked all over the tundra…. My father was always busy mending things. My mother was always busy drying fish…. As long as someone was watching over us, we always felt safe.” Her semi-nomadic family dwelt in such isolation that, for the first few years of her life, Nungnik thought they were the only people in existence. Occasionally, her father would leave their camp and take fox and wolf pelts to trade in some distant and mysterious place. When he came home, she said, he brought with him “strange and beautiful things.”

Top: Artefacts, 2004, wool felt, embroidery floss and beadwork on wool duffel, 18 x 28.5 inches.

Bottom: Kiviuq and His Journeys, 2007, wool felt, embroidery floss and beadwork on wool duffel, 35 x 57 inches.

Nungnik’s life changed radically when she was about six or seven and government agents arrived by plane to take her, her brother and her older sister Vera away to residential school. “I remember the red plane landed and we didn’t know what it was—no clue what it was—and people started coming out and they had different skin. We three children were really frightened. We didn’t want to let go of my mum or dad’s hand,” Nungnik said. Somehow, her father arranged for his children to be moved to Baker Lake, where they could attend day school and live with their parents, once they arrived there, too. Still, this plan was not immediately understood by the Anautalik kids as they were being forcefully removed from all that they knew and loved. “My brother and I were really crying, but my sister comforted us,” Nungnik said. “We went inside the plane. It didn’t have seat belts. We were just sitting there crying. It was really loud. We thought we were inside a big bird of some kind.”

The children were enrolled in school and placed in a foster home in Baker Lake until their parents could be with them again. (William and Martha had to wait months for weather conditions that would allow them to travel the great distance with their dog team.) Nungnik recalls being at school, desperately homesick, desperately missing her parents. “It was very, very difficult to learn because in the back of your mind, there’s always pictures.” She was haunted especially by images of her mother crying as she and her siblings were taken away. “In those days, teachers had rulers and if you misbehaved, ttsskk, you got a big slap.” Still, despite her vivid recall of these experiences, Nungnik’s art rarely registers her pain and sorrow. Instead, she said, she creates works that make other people happy.

At school, she was eventually consoled by the peaceful attitude of a teacher. “His name was Mr. Webster and he was always so calm. After I saw him, I was interested in learning English.” Then she adds, “My classmates were like me, abducted from their homeland. But we connected really well and we had an opportunity to have fun each day.” Later on, while she was home on breaks from middle school in Churchill and high school in Yellowknife, her father insisted that she and her sister and brother maintain their first language—written and spoken. Not incidentally, she signs all her work in Inuktitut syllabics.

Once she settled into school, Nungnik said, she revelled in learning and was keen to pursue her studies. “I really loved math, I really loved social studies, I really loved sports,” she said, then she added, with an ironic and knowing laugh, “I hated sewing.” She began to make wall hangings only in the early 1970s, inspired in part by the legendary Jessie Oonark, whom she helped care for in the elder artist’s later years. “She would say, ‘Look at all the material that I have, look at all the thread that I have—if you want to help yourself, be my guest,’” Nungnik said. “But I never took anything of hers, I just observed because I respected her very much.” She also observed and worked with her own mother, another of the first generation of Baker Lake textile artists.

…to continue reading the article with Janet Nungnik, order a copy of Issue #151 here, or SUBSCRIBE today!