Barry Schwabsky’s PictureLibrary: Checking Back In

Lina Scheynius, Janet Sternburg, Charles Johnstone, Yelena Yemchuk

“But I reckon I got to light out for the Territory ahead of the rest, because Aunt Sally she’s going to adopt me and sivilize me and I can’t stand it. I been there before.” “They hand in hand with wandering steps and slow, / Through Eden took their solitaire way.” “And they all lived happily ever after.” Every book has an end, but there’s always an end after the end. And for anyone alive and making books, there can always be another book. This is the 10th instalment of “Picture Library,” and it seemed like an apt moment to look back while looking forward. How? By checking back in on some of the artists whose books I’ve written about previously, looking at the newer work they’ve done since then, looking for the story after the end of the story.

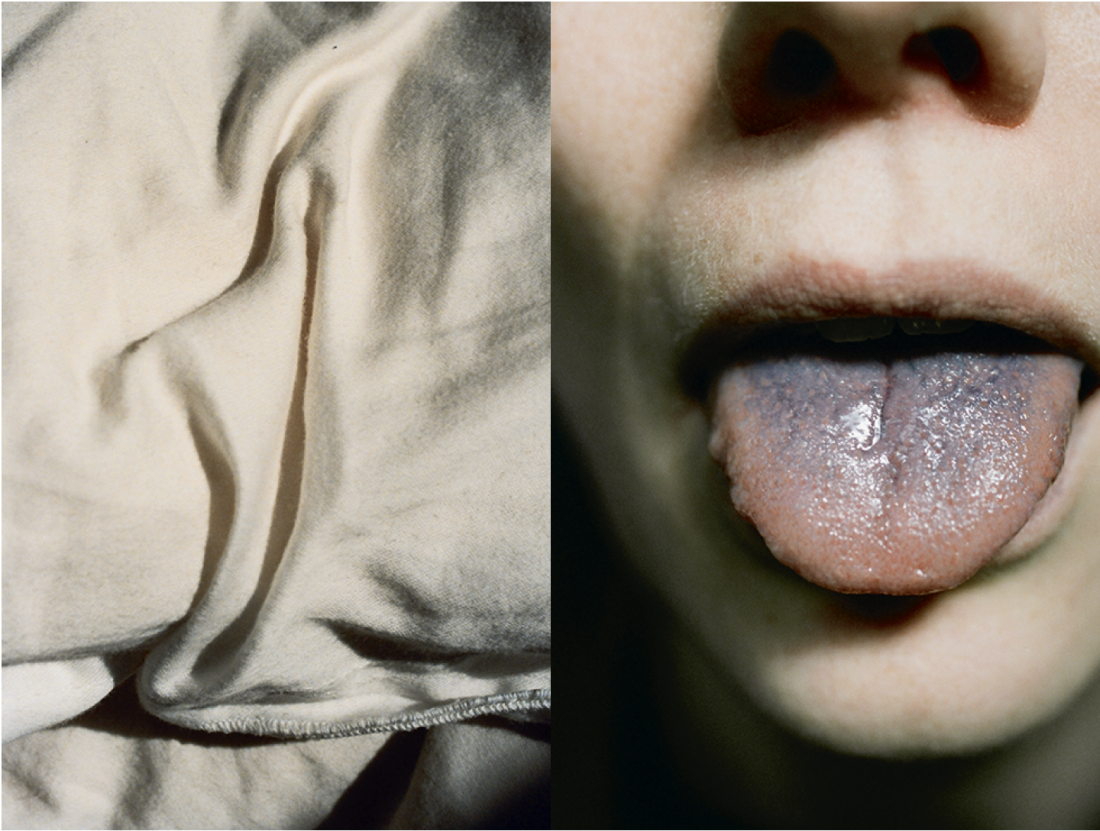

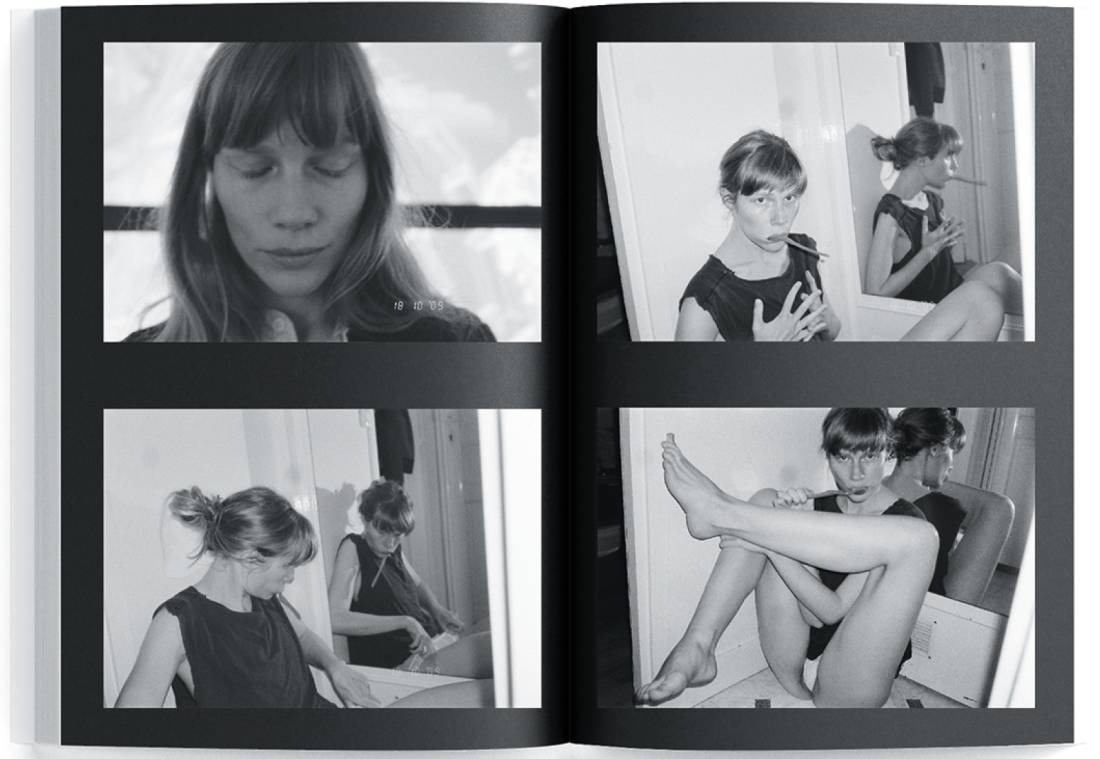

I’ll start with Lina Scheynius: In 2019 the Londonbased Swedish photographer published My Photo Books, a boxed republication of 11 numbered volumes that had been issued separately between 2008 and 2018. It seems that she considered these to be a closed sequence but then recognized that, yes, there’s a story after the end of the story. In 2023 she announced the release of three new publications: 12, 13 and 14, all (like the box set) from JBE Books, Paris, in editions of 1,000. “12 came easily and joyfully, it was ready to be born,” she writes. “13 was a beast to tame and the one that took the most out of me. 14 was a journey back in time full of memories and tenderness and quite a puzzle.” Books 12 and 13, with photographs from 2017 to 2019 and 2019 to 2021 respectively, are in substantial continuity with Scheynius’s previous numbered books: slender paperbacks compiling mostly colour images that gaze ardently at the skin of things, a kind of tactile vision. Scheynius has a special affinity for raking light, especially as it caresses the human body, female or male or ambiguous of gender, usually seen with an intimate propinquity. Shadows veil forms and sculpt them. People are revealed in parts because the whole is presumed: to be pictured is to be addressed, and the addressee need not be told who they are.

What distinguishes the two books is their density. 12 makes lots of space for its 40 white-edged photographs, each facing the blank verso of the one before. The rhythm is slow and airy. A picture in book 12 that I keep returning to most often is a detail of a face, seen sideways, with the shadow of an eyelid cast vertically over a single blue eye. The pupil becomes a dark moon in a miniature cosmos. And then the next photograph shows the moon itself, the ordinary one we know, looking down from a featureless blue sky; from one page to the next, things have been turned inside out, a reversal of scale has been accomplished. By contrast, the 60 full-bleed images of 13 are packed in chockablock, pushed up against each other, keeping the eye constantly off balance, pleasantly dizzy.

Book 14 is something else altogether, and reaches back to near the beginning of Scheynius’s book project, with photographs from 2009–10, over 400 of them, all black and white, two per page with black margins. Back in 2015, Scheynius told an interviewer, “I keep a lot of photos in boxes and occasionally I will go through them and find something I had missed the last time I did.” Not only taking photographs but seeing them again is artistic endeavour. Scheynius’s work is often referred to as diaristic, which can be misleading—a typical book of hers is diaristic only in the sense that a haiku sequence might be called diaristic, which is that it records things seen in daily life. But haiku are not about the “I” of the poet and neither are most of Scheynius’s images an examination of the I of the artist. Who is shown in them? We often don’t know and for the unacquainted viewer it doesn’t matter. The body, even one’s own, is the not-I of the seer—veritably, the other that, as Rimbaud knew, I am. But exceptionally for Scheynius, 14 really is a kind of retroactive diary, a book of self-portraiture, the work of a woman trying to see herself, to understand who she might be. Or rather, the photographs are those of someone trying to see who she might be, but it’s the book of someone trying to see who she might have been. A kind of box full of the past.

Lina Scheynius, Book 12, Book 13 and Book 14, edition of 1,000, published by JBE Books, Paris, 2023.

Lina Scheynius, Book 12, Book 13 and Book 14, edition of 1,000, published by JBE Books, Paris, 2023.

Lina Scheynius, Book 12, Book 13 and Book 14, edition of 1,000, published by JBE Books, Paris, 2023.

Lina Scheynius, Book 12, Book 13 and Book 14, edition of 1,000, published by JBE Books, Paris, 2023.

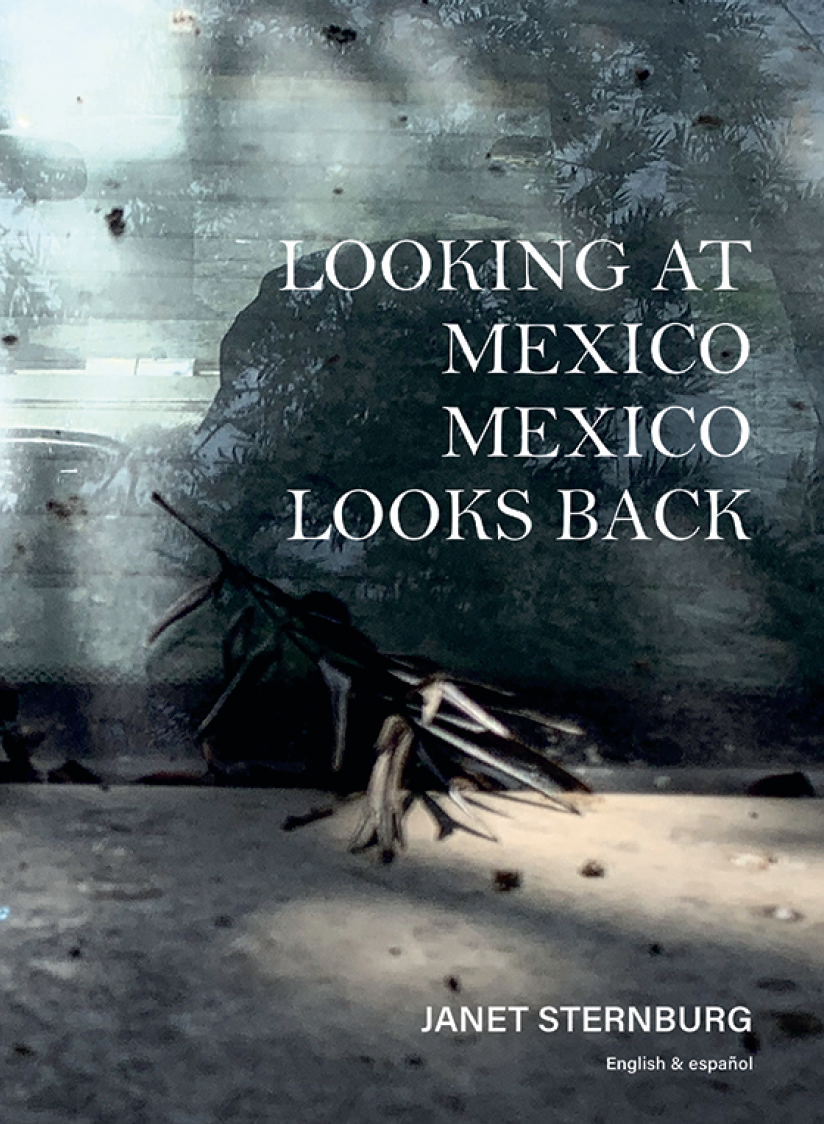

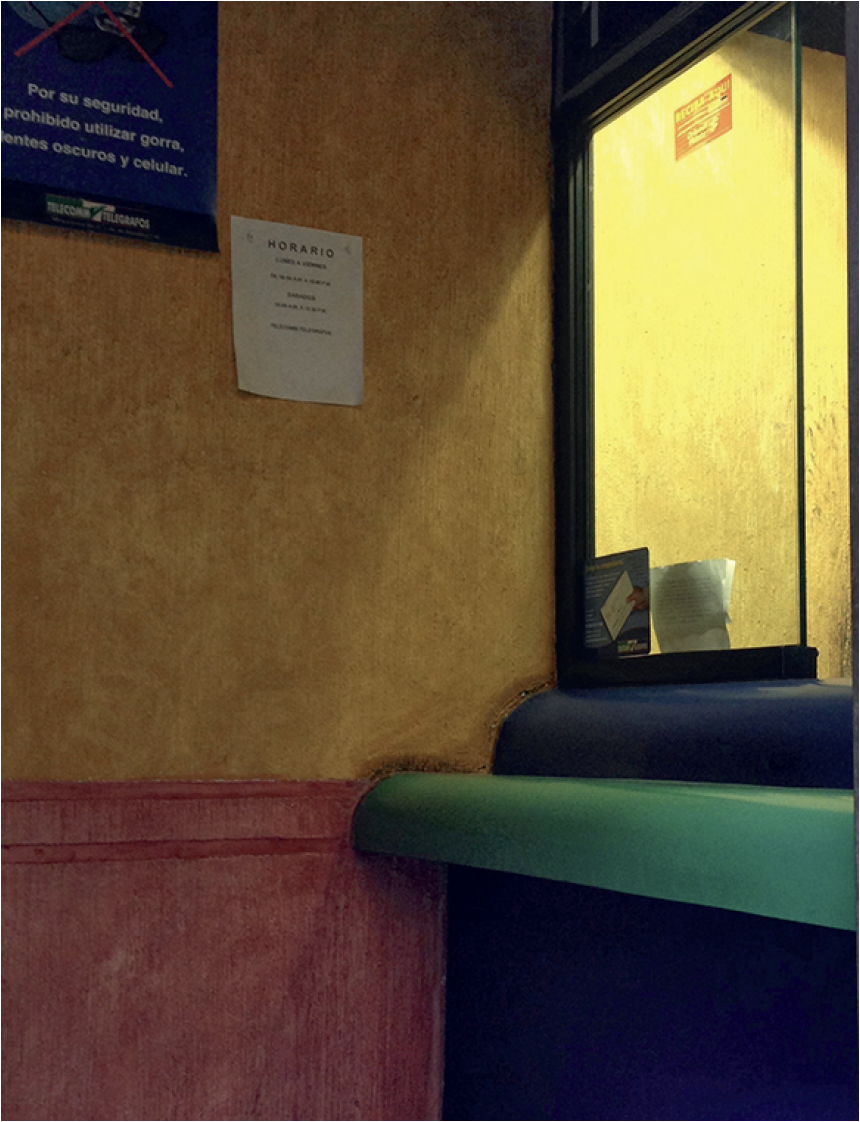

Next, Janet Sternburg: We last caught sight of her with I’ve Been Walking: Los Angeles Photographs, 2021, which was not-a-COVID-pandemic-book (so she averred) in a way that only a COVID pandemic book could ever have been, revealing a city teeming with invisible life. Her new publication is Looking at Mexico/Mexico Looks Back (Distanz Verlag, Berlin, 2023). The setting is the former Angeleno’s new home, the town of San Miguel de Allende in central Mexico where she moved to in 2022. But the methodology is similar: what she calls “solitary walking magnetized by light” but with a new form of uncertainty added: “How do I make a book that isn’t only a gringa’s way of looking at ‘my’ Mexico?” Part of the answer, beyond editing to try to eliminate unwitting stereotypes, was to ask a Mexican friend, José Alberto Romero Romano, to collaborate with her on writing commentaries on the images. (Sternburg’s introduction and Romano’s commentaries are presented in both English and Spanish.) The images, with their collage-like suturing together of seemingly unrelated fragments across a single plane—that plane being visible reality itself, confronted without digital manipulation, double exposures, or other such effects—have become even more mysteriously layered. The commentaries can resolve some of the puzzlement but only some: “The blanket is protection against the mirror breaking.” Okay, but why is it that the mirror seems, at once, to be leaning precariously atop an upright sheet of corrugated cardboard and flat against the photograph’s picture plane? “A stone not to sit on but to look at.” Fine, but why does the broken-off piece of stone with a child’s vision of a house painted on it seem to be floating atop a watery reflective surface of … what? All this would amount to a sort of formalism that is not unfamiliar, albeit often brilliantly expressed, but then the photographs often exude a tenderness that can’t quite be reconciled with a merely cool eye for ambiguous composition. Romano gives a clue about this in commenting on a very close-up image of a detail of a devotional painting in a frame, with some little portrait photos slipped into the frame in front of the painting’s edge: a perfect, naturally occurring, glueless collage. Romano’s grandmother, he says, “puts as many as 20 or 30 small photographs along the side of a picture,” namely that of the Virgin of Guadalupe. “My grandmother is saying to the Virgin, ‘Please take care of my son, and his wife and child.’” Do Sternburg’s pictures harbour this kind of will to care? I think something like that must be the case.

Janet Sternburg, Looking at Mexico/ Mexico Looks Back, published by Distanz Verlag, Berlin, 2023.

Janet Sternburg, Looking at Mexico/ Mexico Looks Back, published by Distanz Verlag, Berlin, 2023.

Janet Sternburg, Looking at Mexico/ Mexico Looks Back, published by Distanz Verlag, Berlin, 2023.

Janet Sternburg, Looking at Mexico/ Mexico Looks Back, published by Distanz Verlag, Berlin, 2023.

Janet Sternburg, Looking at Mexico/ Mexico Looks Back, published by Distanz Verlag, Berlin, 2023.

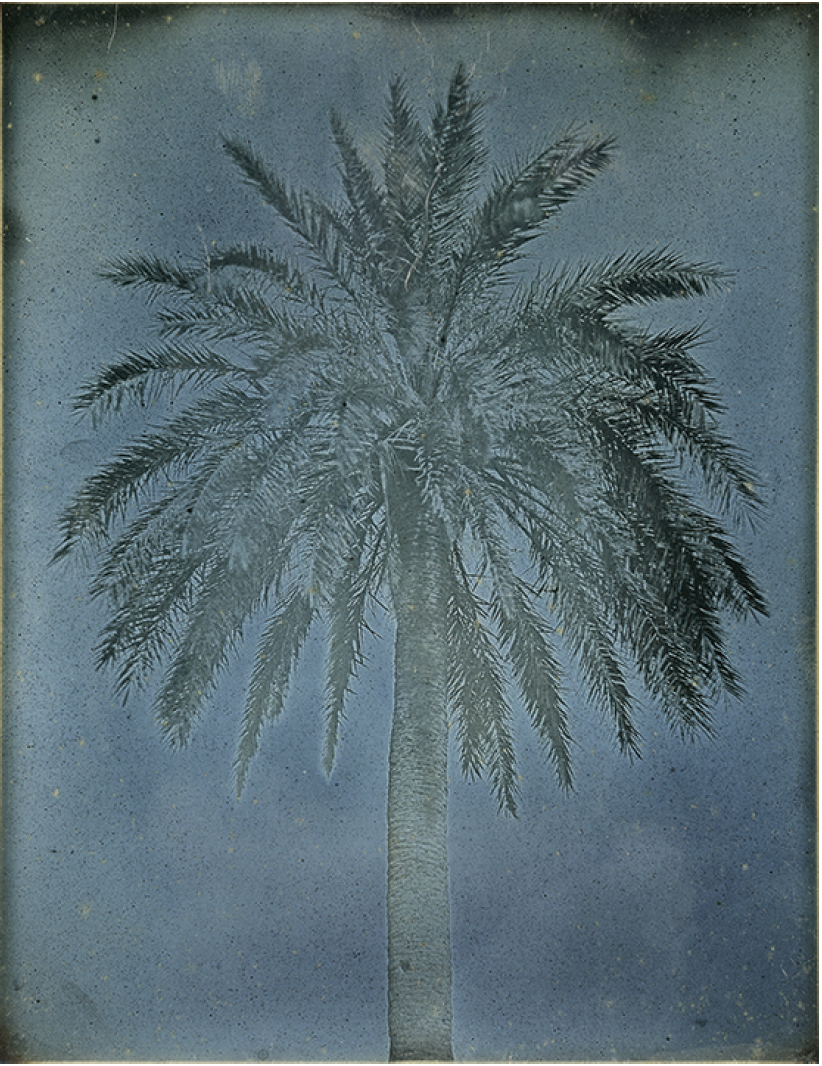

Then there’s Charles Johnstone: His 2021 publication The Summerhouse Pool was a lyrical meditation on the rippling light and shadows of a pool in which one also caught sight of a woman in a red bikini swimming around. An ordinary suburban swimming pool was figured as an emblem of Heraclitean flux and at the same time as a kind of provisional paradise. Since then he’s found a different emblem, as we see in his recent publication In Search of the Perfect Palm: An Homage to Girault de Prangey (Sun, New York, 2023; edition of 120). The ribbon-bound paperback’s dedicatee is a 19th-century archaeologist, architectural historian and earlier adopter of the daguerreotype process, whose photographs were the subject of a 2019 exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was Prangey’s 1842 Palm Tree near the Church of Saints Theodore, Athens that struck Johnstone most forcibly, it seems: “One of Girault’s most original and startling compositions,” as the Met website explains, “this study of the starburst of fronds at the crown of a palm tree feels contemporary even today. The blue cast is a product of the long exposure necessary to reproduce the green foliage, which was hard to capture with the daguerreotype process, particularly against a bright, cloudless sky.” As Johnstone explains in a brief afterword, he used expired Polaroid film to produce aleatory colour shifts in his images, all of which follow his chosen precedent in showing one, two, or many palm trees against variable skies. Only some of the pictures catch a horizon line; more often, its absence seems to raise the trees’ crowns to some unthinkable height. If the swimming pool pictures were all about looking downward, these are a paean to looking up—to aspiration.

Johnstone’s most recent book, too, is a work of homage: Au Revoir Anna (Sun, New York, 2024; edition of 100) is dedicated to Anna Karina, the Danish-born French actress who died in 2019 and was best known for her appearances in the early films of (and her brief marriage to) Jean-Luc Godard. Again, the images are reproduced from Polaroids, this time of shots from films (in not all of which is Karina’s face visible). But in place of the cangiante Prangey-esque azures of the palm pictures, the hues in this later book are mostly a pearly grey, which somehow made me think of the poet Diane Seuss’s uncanny perception: “That all at its essence is dove-gray. / Wipe the lipstick off the mouth of anything and there you will find dove-gray.” Were all those films really in black and white? Or just Johnstone’s memories of them? Karina once spoke of the way of appearing for the camera that she and Godard invented as “more like being than acting”; superimposing a second camera on the cinematographer’s image, Johnstone filters that being through the mesh of memory and nostalgia, and finds its power undiminished.

Charles Johnstone, In Search of the Perfect Palm: An Homage to Girault de Prangey, edition of 120, published by Sun, New York, 2023.

Charles Johnstone, In Search of the Perfect Palm: An Homage to Girault de Prangey, edition of 120, published by Sun, New York, 2023.

Charles Johnstone, In Search of the Perfect Palm: An Homage to Girault de Prangey, edition of 120, published by Sun, New York, 2023.

Charles Johnstone, In Search of the Perfect Palm: An Homage to Girault de Prangey, edition of 120, published by Sun, New York, 2023.

Charles Johnstone, In Search of the Perfect Palm: An Homage to Girault de Prangey, edition of 120, published by Sun, New York, 2023.

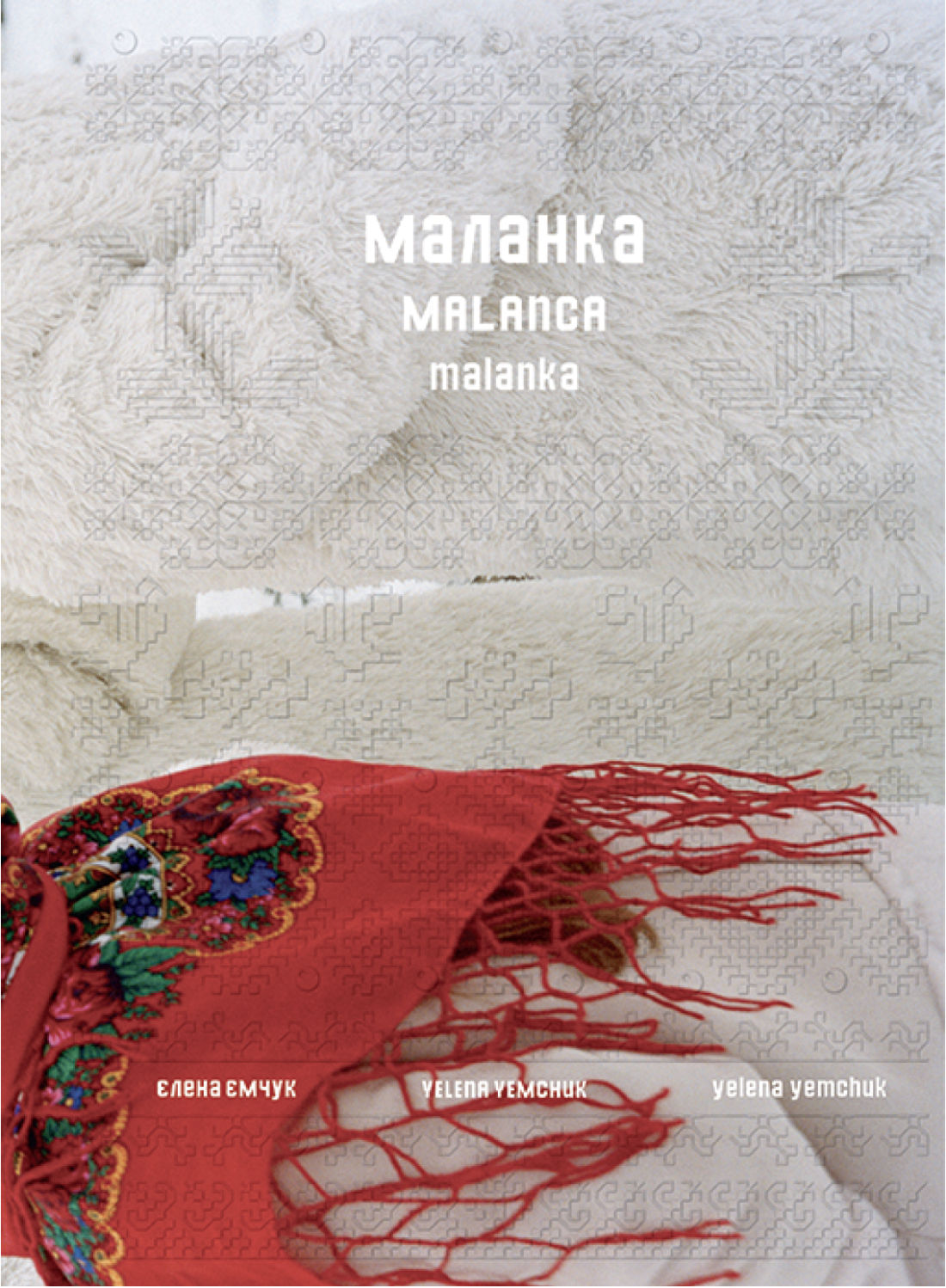

And finally, Yelena Yemchuk: The publication of her book Odesa in 2022 had turned out to be tragically timely. Its images, mostly portraits, were made between 2015 and 2019, yet in retrospect seemed shadowed by the possibility of war, as it broke out that year. Strangely, war seems even more distant than before in her new book Malanka (Edition Patrick Frey, Zurich, 2024; edition of 800), which is named for a Ukrainian form of New Year’s Eve celebration. The 121 colour pictures were made in 2020 in Krasnoilsk, a town in western Ukraine near the border with Romania, and whose inhabitants are ethnic Romanians. A closing essay by Romanian journalist Ioana Pelehatăi describes Krasnoilsk as “the border between tradition and modernity” and its Malanka as “the most spectacular Eastern European carnival.” Her essay, like Yemchuk’s closing dedication and indeed the book’s title page and other framing information, is given in Ukrainian, Romanian and English; it was written three years after the Malanka that Yemchuk recorded, which is to say, after the Russian invasion, and this gap of time serves her to remind us that “to survive, a carnival needs … slightly modified iterations, gradual evolution with each effort.”

Yemchuk’s photographs, as an ensemble, are extraordinary. I want to call them the virtuosic translation of a joyful noise into a pensive silence, or maybe vice versa. I should explain that when I mention “joyful noise,” I don’t mean to imply that the images, one by one, have any particular bent toward crowd scenes, or show people making a racket, or focus on rowdy or rambunctious behaviour—nothing like that. There’s plenty of comedy here, but (at least to a foreign eye) it’s understated. The most recurrent character is the snow-covered terrain. But these pictures and the people who inhabit them evince an unshakeable solemnity; and for all the fantasy invested in the carnivalesque masks and costumes—topical or traditional as they may be—they feel grounded. It’s the rhythm of the images’ collocation, the abrupt encounters of distinct compositional dynamics, that lend the book a boisterous energy one would not have noticed except in the ensemble, an energy above and beyond the more concentrated gravity of the individual frames. This, really, is the kind of thing for which I decided, a few years ago, to cultivate a deeper interest in photo books: to more vividly experience and better understand the poetics of composition across and not only within images. ❚

Yelena Yemchuk, Malanka, edition of 800, published by Edition Patrick Frey, Zurich, 2024.

Yelena Yemchuk, Malanka, edition of 800, published by Edition Patrick Frey, Zurich, 2024.

Yelena Yemchuk, Malanka, edition of 800, published by Edition Patrick Frey, Zurich, 2024.

Yelena Yemchuk, Malanka, edition of 800, published by Edition Patrick Frey, Zurich, 2024.

Yelena Yemchuk, Malanka, edition of 800, published by Edition Patrick Frey, Zurich, 2024.

Yelena Yemchuk, Malanka, edition of 800, published by Edition Patrick Frey, Zurich, 2024.

Barry Schwabsky’s recent publications include a monograph, Gillian Carnegie (London: Lund Humphries, 2020), and the catalogue for the retrospective exhibition “Jeff Wall” at Glenstone Museum, 2021. His new collections of poetry are Feelings of And (New York: Black Square Editions, 2022) and Water from Another Source (New York: Spuyten Duyvil, 2023).