Barry Schwabsky’s PictureLibrary: Changes of Focus

Janet Sternburg, Teju Cole, Mark Peckmezian, Charles Johnstone

Was it really only two years ago and a bit that the lives of all of us somehow changed, each in our own way? As for me, I lost all sense of focus for a while, and yet I noticed that over the 18 months beginning March 2020 I wrote about as much poetry as I had in the previous six years. In my brain something had shifted before I’d realized it. As a change of focus can make nearer things seem nearer and farther ones even more distant, the pandemic made necessary things more necessary, superfluous ones totally dispensable.

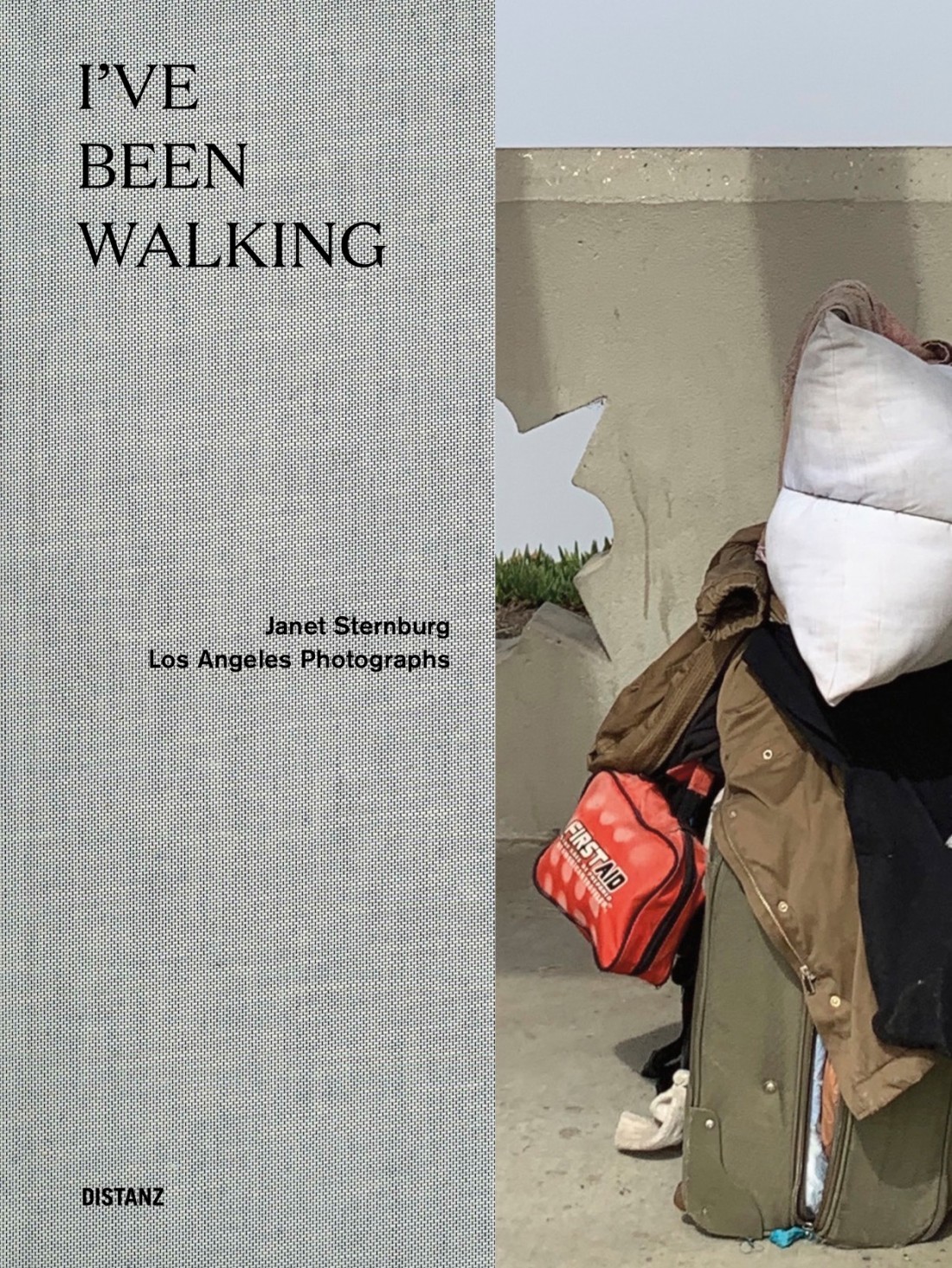

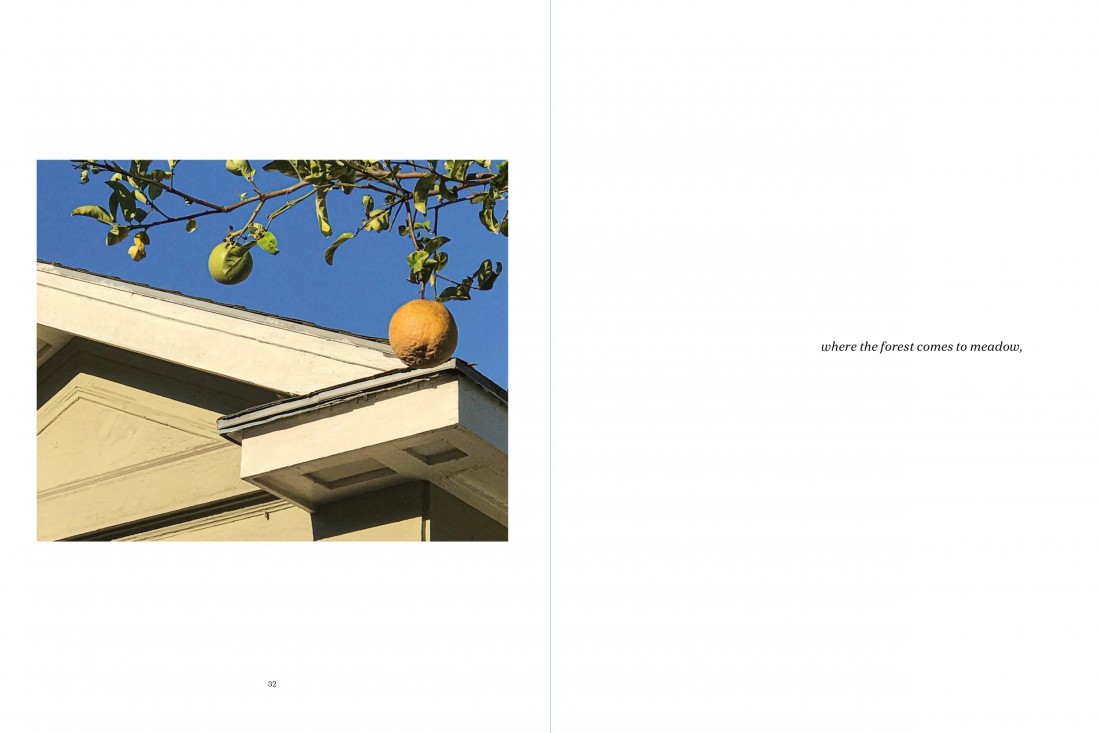

Janet Sternburg, I’ve Been Walking, published by Distanz Verlag GmbH Llc, 2021.

Janet Sternburg, I’ve Been Walking, published by Distanz Verlag GmbH Llc, 2021.

Janet Sternburg, I’ve Been Walking, published by Distanz Verlag GmbH Llc, 2021.

Depending on circumstance, predilection and fortune, people I know seem to have spent either much more time inside or much more time outside. Los Angeles-based photographer Janet Sternburg is one of the outsiders. She spent her pandemic walking, which as we all know is an unaccustomed way of being in that city—a good way of seeing it differently, as it turns out. And yet, “I’m not documenting Los Angeles during the pandemic,” she insists in her introduction to her new book, I’ve Been Walking: Los Angeles Photographs (Distanz Verlag, Berlin, 2021). “Nor am I trying to present a comprehensive view of the city,” she continues. It’s more about the tangent at which a gaze meets a surface. The narrative, if you can call it that, is of an observer in movement. And what’s to be observed? Not the usual subject matter of street photography, namely other people. They are almost entirely absent from these pictures—I said almost. You can catch some out of the corner of your eye: a man painting a green wall a lighter shade of green; the shadow of someone walking a dog cast on a cinder block wall; a skateboarder’s feet, the rest of whose body is hidden by a textured glass window; one or two others. Most importantly, the observer herself is not observed, so a certain form of self-consciousness is evaded.

But still, it’s a city, teeming with human life, and everything in it speaks of the people who are hidden somewhere around. There are windows, sometimes guarded by ancient, bent Venetian blinds; what’s on the other side? Sometimes one sees, but only fitfully, through the glare reflecting off this side of them. Mattresses left out on the sidewalk, traffic lights, graffiti, things that are ultimately anonymous. The philosopher Jane Bennett, in a conversation with Sternburg included in the book, compares the images to lists, “discrete things, each packed with resonating forces.” Yes, but these images seem to undermine the discreteness of things, pushing them up against each other. Scale becomes illegible, planes converge. The city is a collage, and so many of Sternburg’s images look like they’ve been produced by cutting and pasting, but no—they’ve been collaged by life, time and perception.

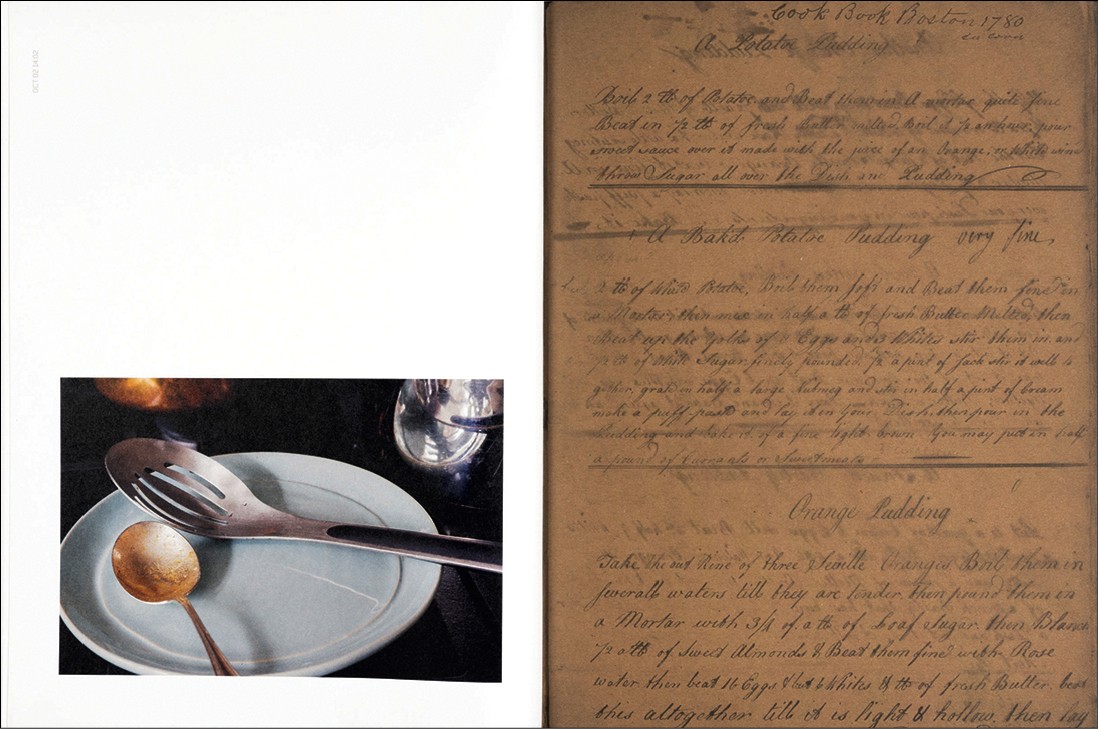

Teju Cole, Golden Apple of the Sun, published by MACK Books, 2021.

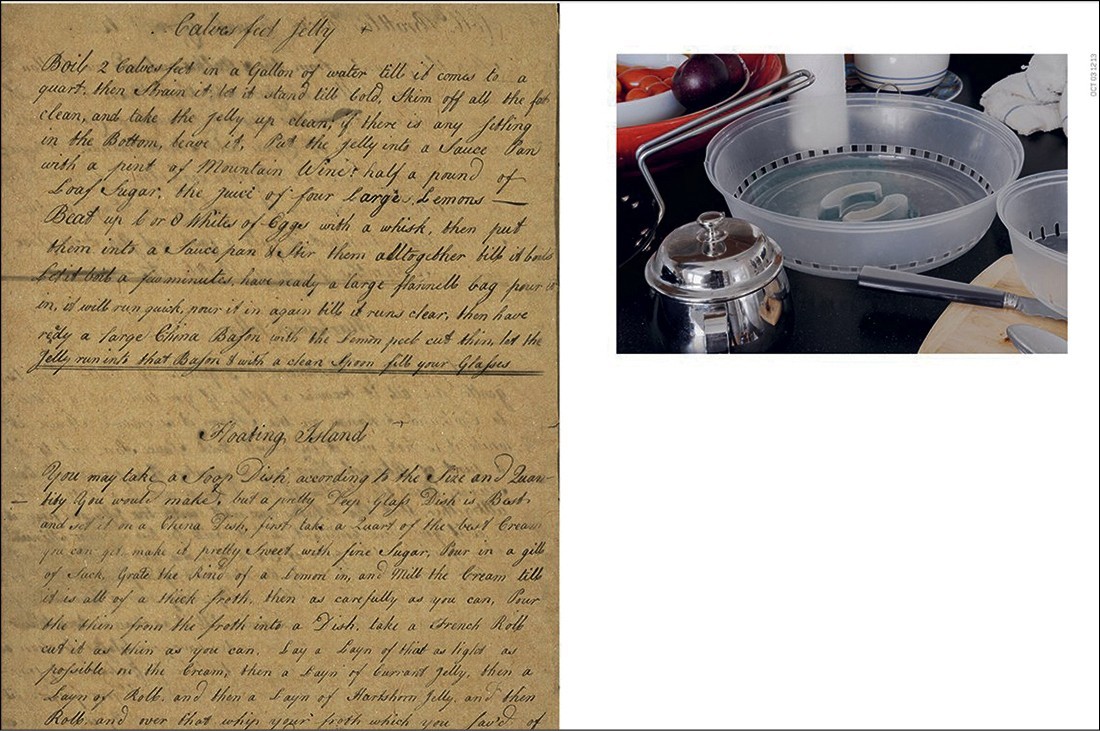

As I’ve Been Walking is a (mostly) outdoor book, Teju Cole’s Golden Apple of the Sun (MACK, London, 2021) is an indoor book. Its images were made in Cole’s kitchen in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the five weeks leading up to the November 2020 US election, a pandemic moment that was also, as the whole time was and is, a political moment. But the pictures are not political in any overt way. They are still lifes. Talk about lists! Dishes, spoons, water glasses, knives, dish towels, spilled water, jugs, pans, cutting boards, placemats, spatulas, pitchers, cheese graters are their protagonists—often in need of washing. And the list could go on: there are even spoon rests. Do people really use those? Are they de rigueur in some milieu I don’t know? Never mind. Just as the people are mostly absent from Sternburg’s cityscape, food is mostly absent from Cole’s kitchenscape. Yes, one notes some sliced lemons here and sliced limes there, an onion—also sliced, as is an apple with its seeds extracted—whereas a round of bread has not, as far as one sees, been cut, neither has an egg been cracked. Apparently Cole’s dinner table has a black top. Things are dim here—shadowy, and the mild intangibility of these images that invoke the things one knows above all by touch is enhanced by a certain graininess that is probably amplified by the matte quality of the paper on which they have been printed. I think about how little one looks at the things one uses every day, how little they claim one’s attention, and realize it’s a sort of perceptual darkness. I am fascinated with the way Cole has managed to catch the sense of this inattention while nonetheless, in fact, paying attention. That seems very beautiful to me.

Teju Cole, Golden Apple of the Sun, published by MACK Books, 2021.

Teju Cole, Golden Apple of the Sun, published by MACK Books, 2021.

Teju Cole, Golden Apple of the Sun, published by MACK Books, 2021.

Interspersed among Cole’s photographs are pages, printed on brown stock, from a handwritten book of recipes dating from the 18th century. They can hardly be read, though it is easier to make out their headings: TO MAKE ALMOND CHEESE CAKE, LEMON CREAM VERY FINE, A GROUND RICE PUDDING—apparently they were very fond of desserts in those days. The book ends with a long essay (Cole is a renowned writer as well as photographer) also on a brown ground—which I regret because this text, at least, should be easier on the eye. It begins as a meditation on hunger—his own, as a boy, when he was at a Nigerian boarding school where the pupils were fed a starchy, repetitive and inadequate diet, and then again, later on, as a penniless and depressed college graduate subsisting on ramen and canned goods. From this base he launches a deeply historical meditation on still life: Chardin, Morandi, all those Dutchmen; but also Jan Groover and Laura Letinsky. It’s a rich, complex, historically informed essay deserving of a responsive text of its own, but here I want only to point to something he says that illuminates what touches me in the images, the idea that for what he was trying to do, “the words I want are neither ‘interesting’ nor ‘boring,’” for it’s in that neither/nor that “some other space has the chance to be created.” What is that space? I don’t know, exactly, but it’s a place of nourishment, of care for the future, and of noticing the strangeness of imagining that such things might be possible.

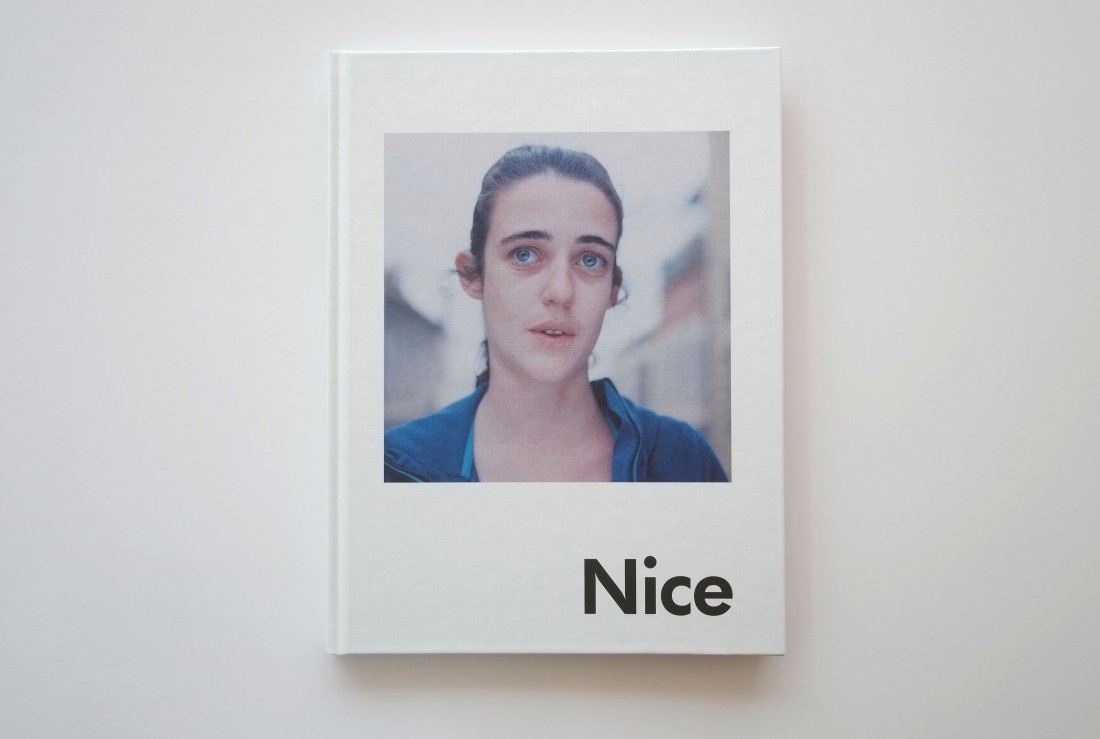

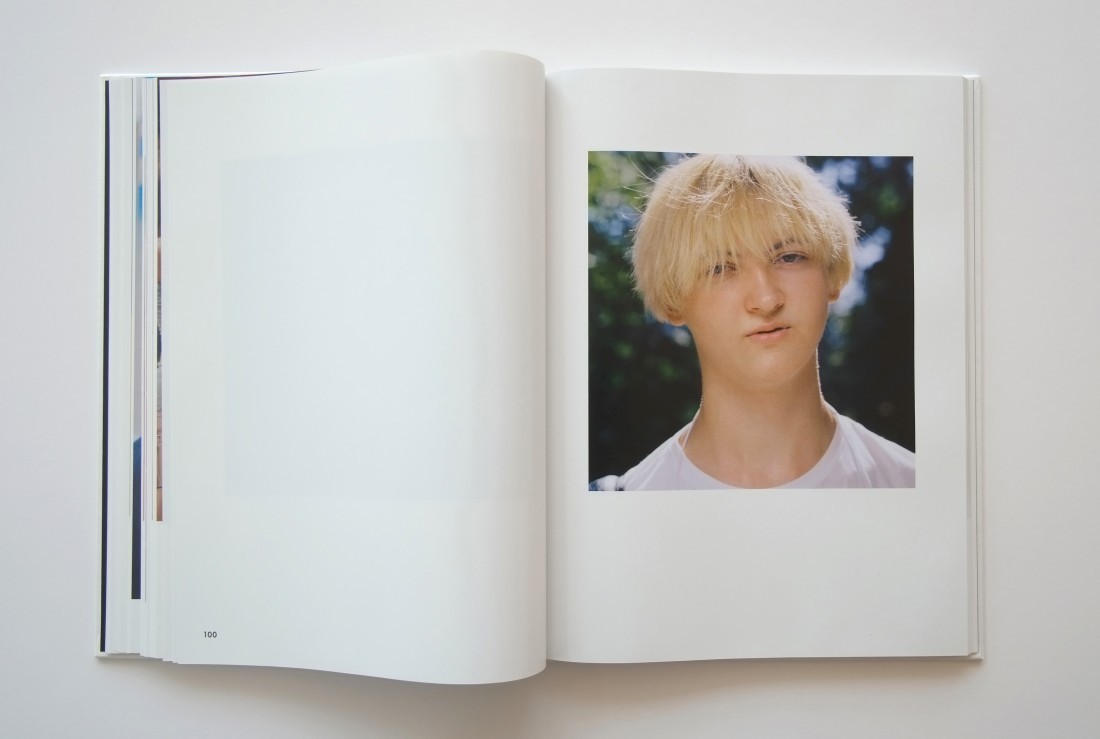

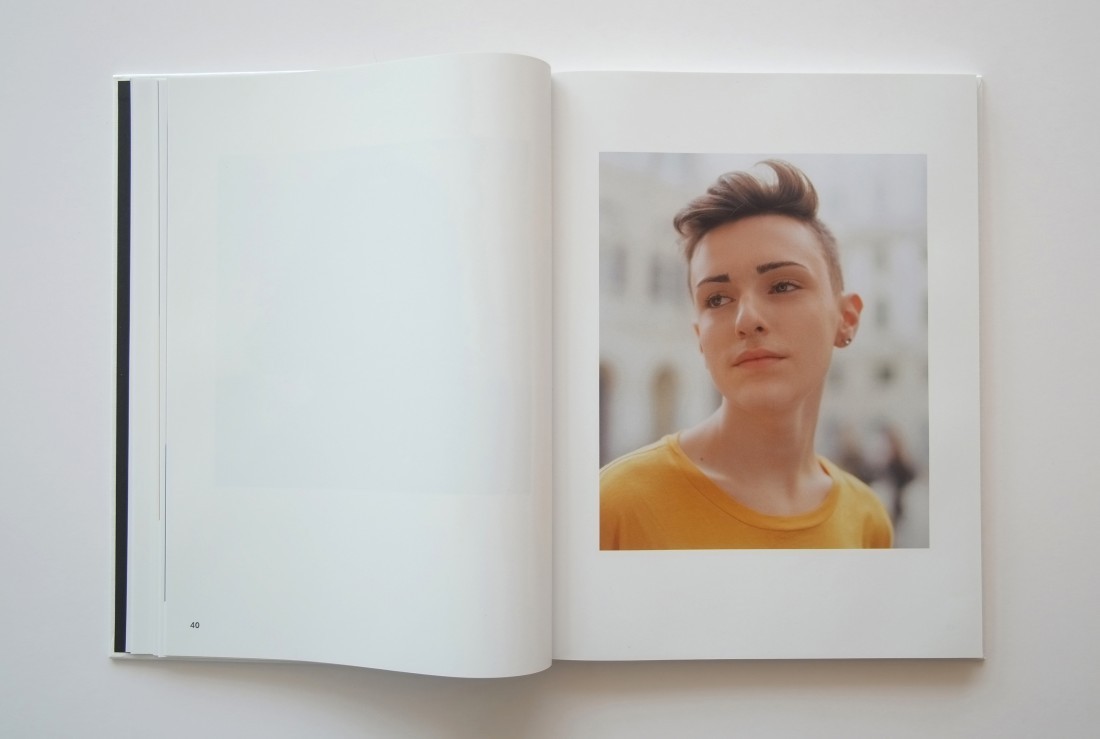

Mark Peckmezian, Nice, published by Roma Publications, 2021.

Mark Peckmezian, Nice, published by Roma Publications, 2021.

Mark Peckmezian, Nice, published by Roma Publications, 2021.

Mark Peckmezian, Nice, published by Roma Publications, 2021.

“How exhilarating and terrifying to be looked at, to be seen—to realize you’ve been an image this whole time”: so reads in part the only text (title and colophon pages aside) in Nice, the first book by Toronto-born, Berlin-based photographer Mark Peckmezian (Roma Publications, Amsterdam, 2021; edition of 2,000)—found on its back cover, like an afterthought. That heightened delight and anxiety about the gaze of others is particularly acute, I think, in youth; and so the hundred-plus mostly colour portraits compiled in the book, edited and designed by the well-known magazine publisher Jop van Bennekom, are all of young people. Their faces fill the frame, sometimes claiming it as their inalienable right, other times occupying it with a sense of skepticism or incomprehension, very occasionally looking as if they wished they could have evaded it. And mostly they are just faces, the rest of the body (and its clothing) being out of the frame, as if that would have presented more problems—for the subjects? for the photographer?— than Peckmezian’s generous yet disinterested gaze was willing to take on. Likewise, the backgrounds are for the most part a blur; although Peckmezian, with his active fashion and editorial practice, has apparently had an opportunity to scout out his subjects in cities around the world, location is irrelevant in comparison with the sense of self—or rather, of self-image—in formation.

There is a wonderful frankness in many of the gazes that meet Peckmezian’s camera—an innocence, dare I say it, that does not elide the complexity of feeling about submitting to someone’s request to become an image. And yet, paradoxically, something deeper seems revealed when you sense things are held back. If I had to choose a favourite image in the book, it would be the third from the last, unusual in that the subject, a turtlenecked girl with shoulder-length blonde hair, turned at a threequarter view, shown from about the elbows up, stands not in a city but in a field, under a postcard-blue sky, with a single-storey building as featureless as a minimalist sculpture at a distance behind her and a red car in front of it, mostly behind her head. The gash of red and harsh sweep of blue may be as intense as the thoughts she harbours behind eyes she’s keeping determinedly shut, as if to defend them from the photographer’s inquisitive gaze—or maybe she’s just enjoying the radiance of the sun on face. Thank goodness, really, the picture can’t pretend to tell us.

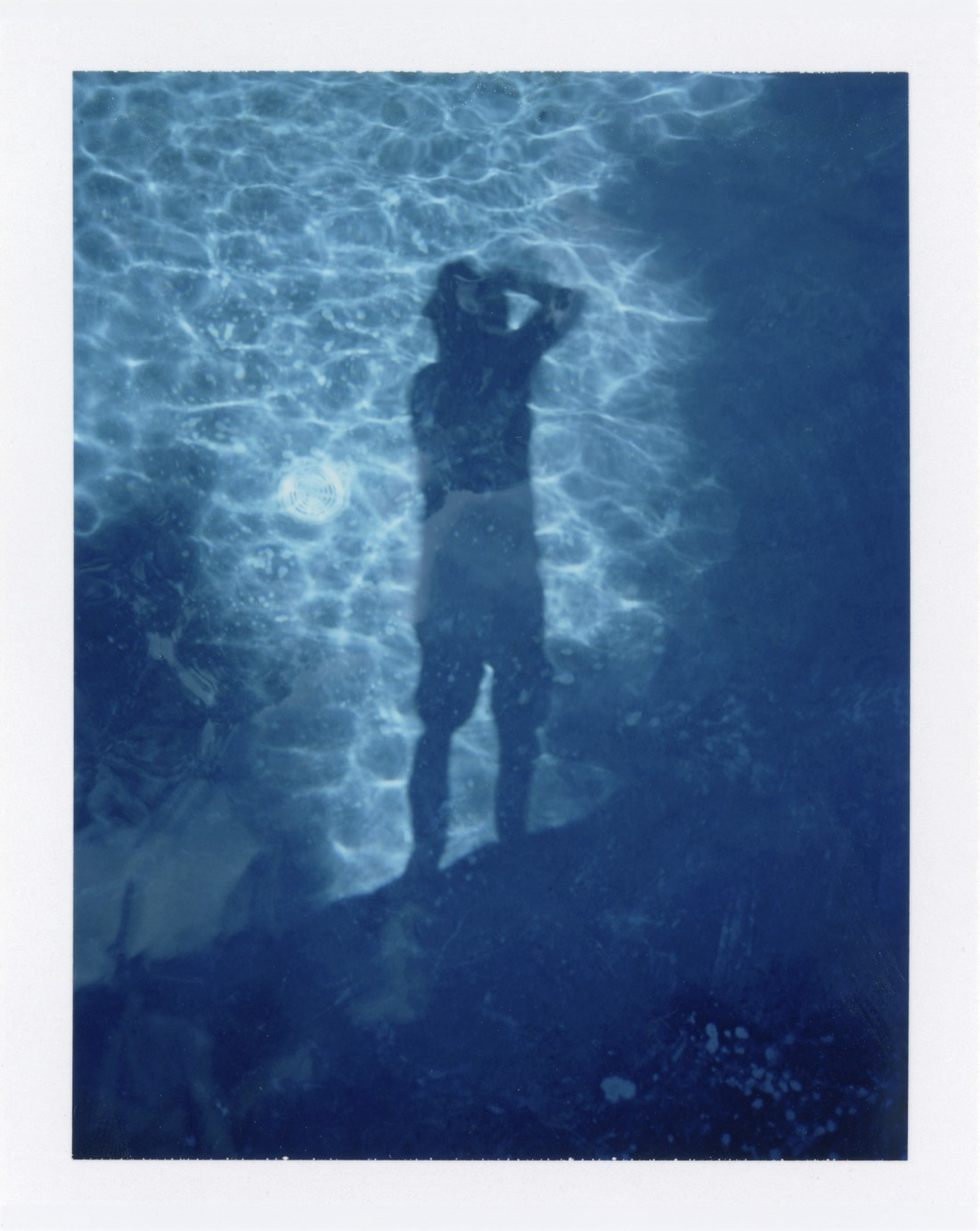

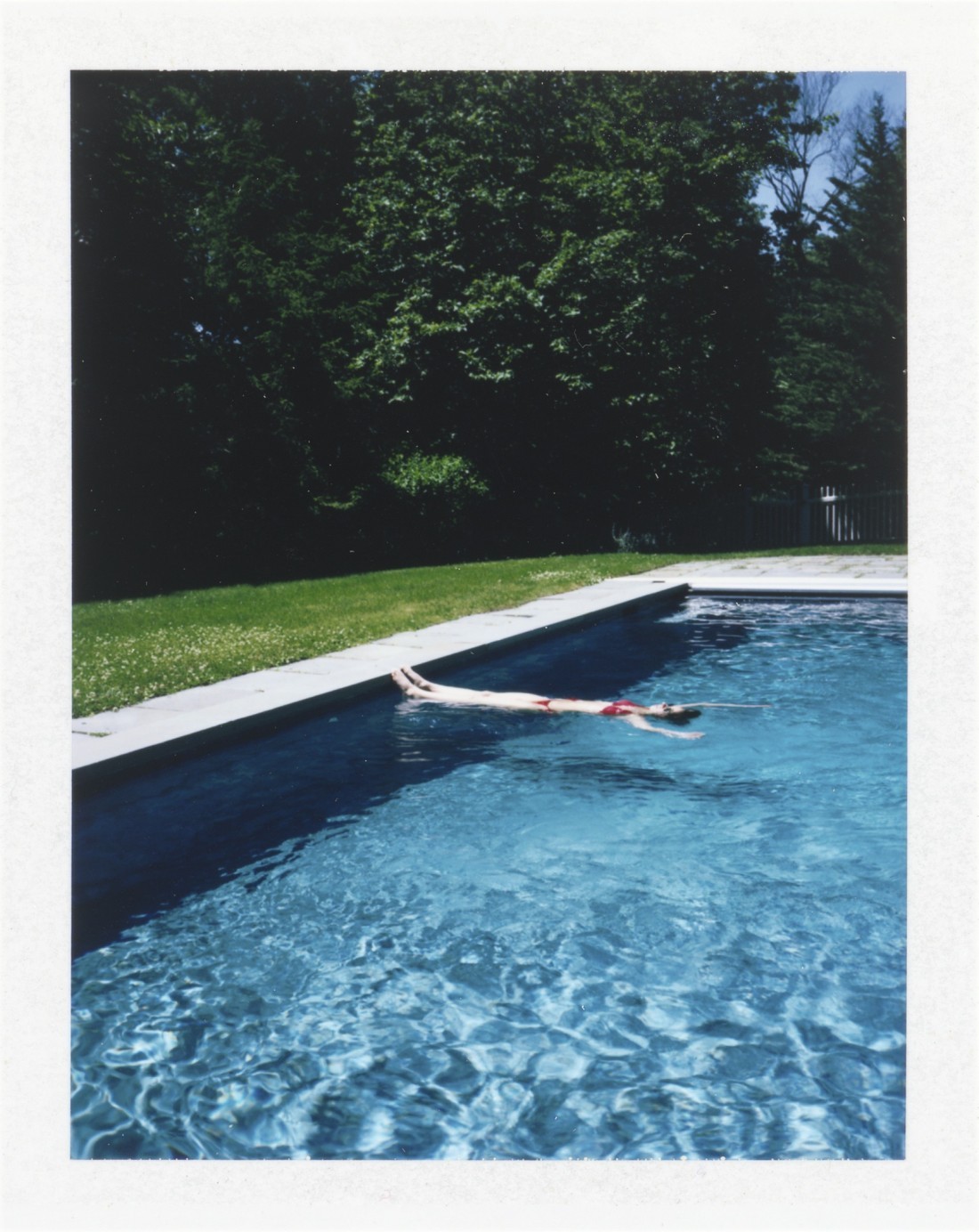

Charles Johnstone and Lea Simone Allegria, The Summerhouse Pool, published by SUN Editions, 2021.

Charles Johnstone and Lea Simone Allegria, The Summerhouse Pool, published by SUN Editions, 2021.

Charles Johnstone and Lea Simone Allegria, The Summerhouse Pool, published by SUN Editions, 2021.

Charles Johnstone and Lea Simone Allegria, The Summerhouse Pool, published by SUN Editions, 2021.

Charles Johnstone has been known for photographic series that are very much in the mode of Ed Ruscha’s classic book works: deadpan typologies of the urban scene. But where Ruscha catalogues the sights or non-sights of his southern California environs, Johnstone has focused on what could be seen from the sidewalks of New York. Thus, in place of Ruscha’s Thirtyfour Parking Lots of 1967, in 2008 Johnstone presented Thirtyfour Basketball Courts—which is not to say that the Big Apple is as short on parking as its denizens may claim, or that LA lacks ball; the difference is more about sensibility than empirical fact. Johnstone has also fixed his gaze on handball courts, municipal swimming pools (off-season, empty) and storefront churches. As blunt, frontal and seemingly straightforward as his compositions are, Johnstone’s emphasis is not so much on banality as on the beauty within banality. He’s a connoisseur of surfaces, showing everyday sights as a feast for the eye. In his most recent publication, The Summerhouse Pool (SUN, New York, 2021; edition of 100), he makes his sensualism even more explicit with a venture out of the metropolis, in 22 Polaroids, reproduced at actual size, of a swimming pool set behind a little white house in a verdant suburban (or maybe it’s even rural?) setting. In a few of the images you glimpse a young woman (her name is Lea Simone Allegria and, having also drawn the illustration of a pair of chaises longues on the publication’s cover, she is listed on its title page as Johnstone’s collaborator, not just his model) in a red bikini swimming—more than glimpses of her in just a couple—and occasionally you can make out the shadow of someone standing by the side of the pool, which would be the photographer himself. But most of the images are unpeopled. The subject really is the pool. Johnstone seems to be seeking down there in the ripples of light and cast shadows across the surface of the dark blue water something like what Alfred Stieglitz was looking for in the clouds above. Clouds are nothing but water anyway, though we see them so differently, but what’s interesting about both for the purposes of photography is that it is so hard to see them, to fix on them for and as what they are—they are so elusive, so mercurial and, for that reason, as Stieglitz said, “most difficult to photograph—almost impossible.” Or maybe I should put it like this: The story conveyed by this little book is of the male photographer’s divided attention or rather intention, that is, of a man who, like Stieglitz, wants to make “photographs look so much like photographs that unless one has eyes and sees, they won’t be seen,” and who can’t help but be distracted from this project of abstraction by the fact that he also wants to see and show the elusive human subject, a woman who haunts the scene and his imagination. ❚

Barry Schwabsky’s recent publications include a monograph, Gillian Carnegie (London: Lund Humphries, 2020), and the catalogue for the retrospective exhibition Jeff Wall (Potomac, Maryland: Glenstone Museum, 2021). His new collection of poetry is Feelings of And (New York: Black Square Editions, 2022).