Candice Breitz

Candice Breitz’s Digest at Marian Goodman Gallery in London is simply described: an installation of 1,001 videocassette boxes, the covers of which have been almost wholly obliterated by the impasto application of black acrylic paint. Just one word, painted white, is visible from each title. That may sound schematic and dry, especially compared with the channelling of voices, music and identities characteristic of Breitz’s film work over the past two decades. And yet there is plenty to Digest—as suggested by a title that can operate as noun or verb, that neatly conjoins the bodily and the intellectual, and indicates a summary of data as well as physical or mental absorption.

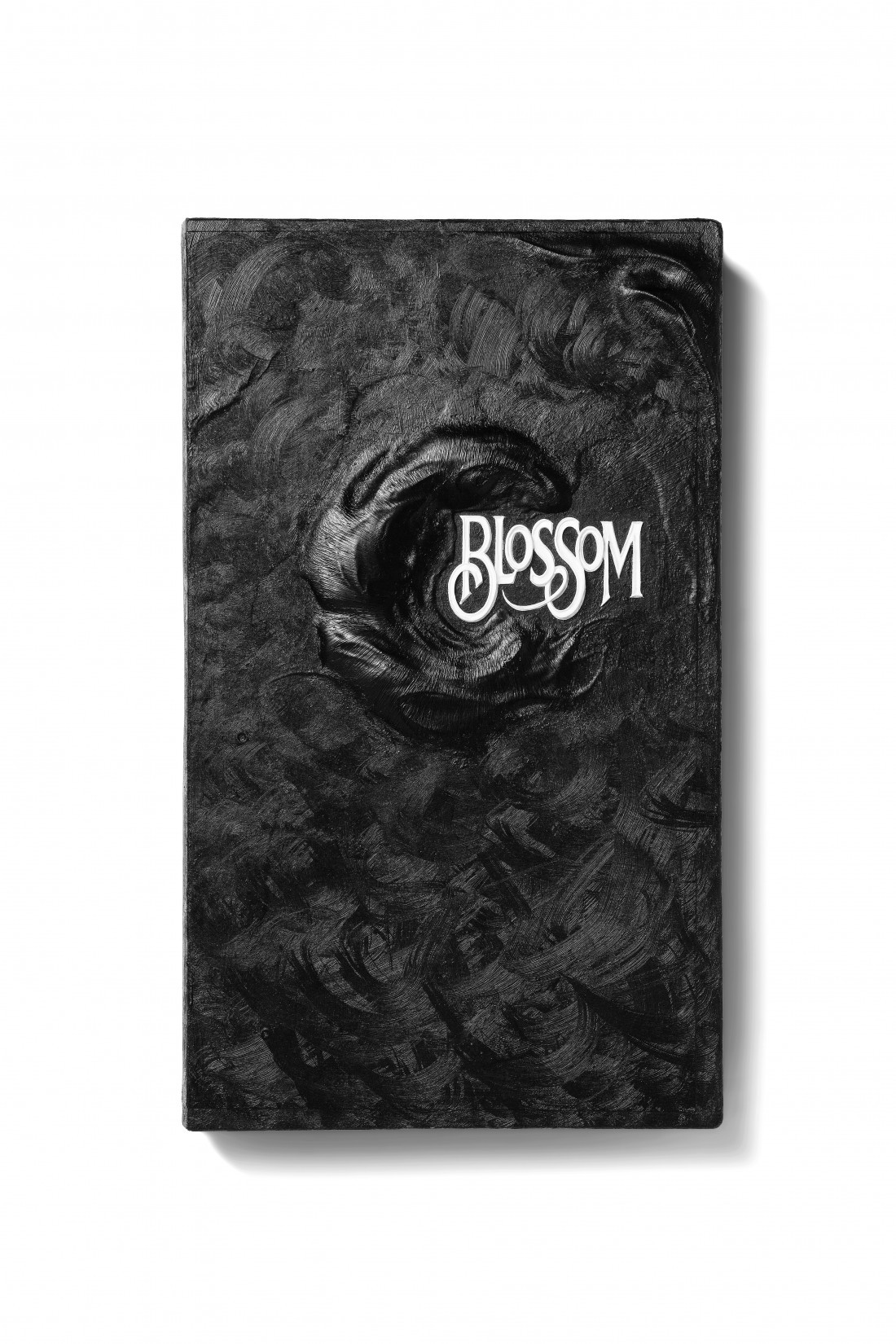

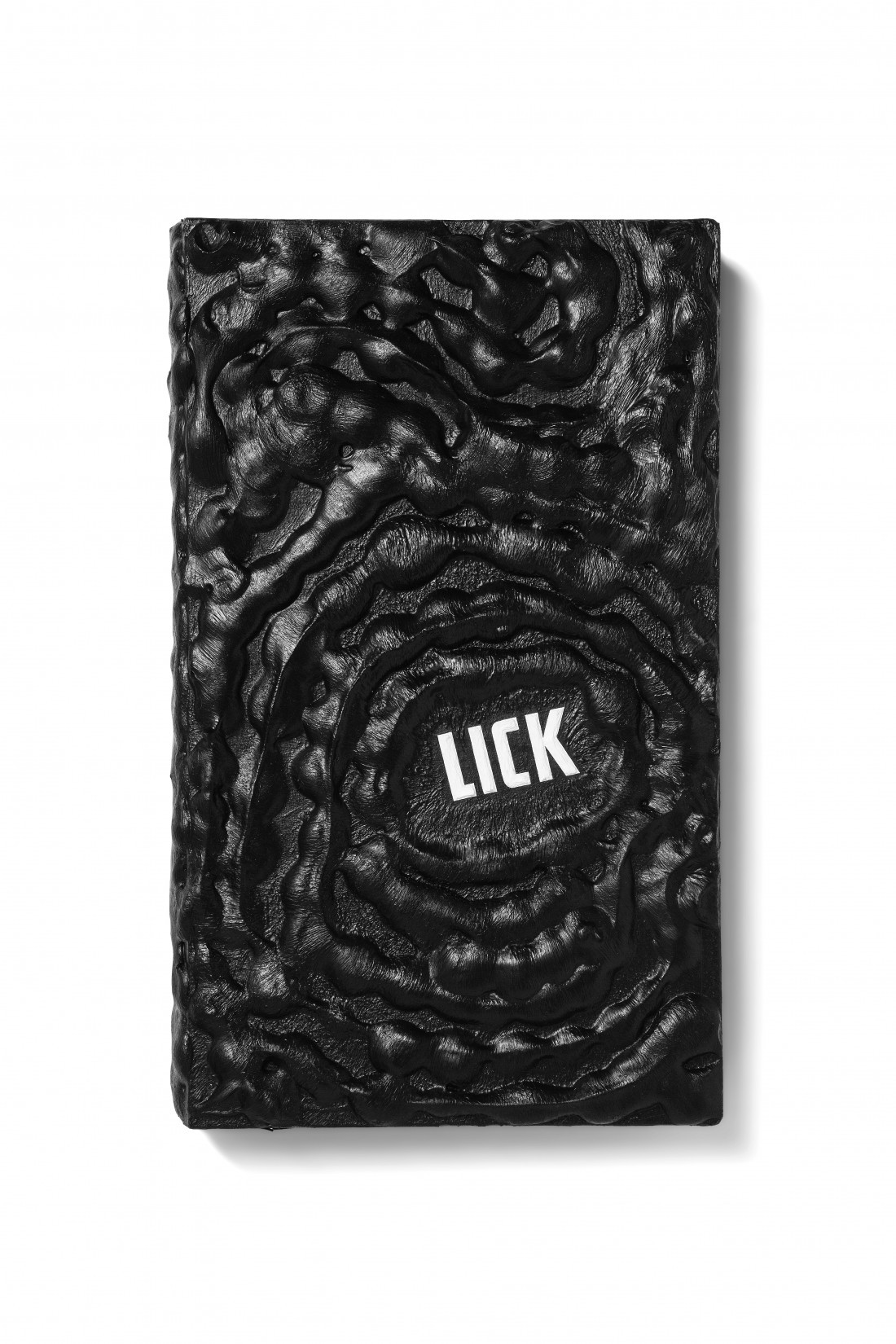

Candice Breitz, Digest (detail), 2020, videotape in polypropylene sleeve, paper, acrylic paint, 20.3 x 12 x 2.7 centimetres. Photo: Saverio Cantoni. Courtesy Marian Goodman, London.

There actually are 1,001 pieces of videotaped film in the boxes, though we can’t find out what they are without destroying them as artworks. The boxes are taken from films made in the 20th century to 2009, all of which were released on VHS. So this is a cultural summary of sorts. The words we see highlighted are from the relevant titles, all replicated in the original position and font, and presented as verbs—though they may have been nouns in their original contexts. The primary inspiration is the framing device of the Arabian Tales from the Thousand and One Nights. Shahryār, the Persian king in the legend, marries a succession of virgins, only to execute each one the next morning to prevent any chance of her being unfaithful. The 1,001st such, Scheherazade, enthralls the king with a tale—but does not end it, causing him to postpone her execution in order to hear the conclusion. This goes on for the following thousand nights, as Scheherazade spins a succession of cliff-hangers. Breitz praises Scheherazade’s “ability to weaponize narrative in order to stay alive in a society governed by patriarchal violence” (Breitz, in conversation with Nora V Scouri, “Never Ending Stories, Interview with Nora V Scouri,” Journal der Künste, 2020), that exaggerated narrative suspense carried through into Digest. We have only fragmentary hints of what stories lie behind the sleeves: not only are the tapes inaccessible, but the figurative imagery that would have appeared has been obliterated. In Breitz’s words, this double negation of narrative provides a space for projection “first for the team members working on it in the studio, and then eventually for the viewer encountering the installation. Sometimes we need to escape the stories that we’ve heard over and over again, in order to come up with fresh new stories and innovative ways of telling those stories. This is perhaps the most important lesson we can learn from Scheherazade.”

The project was carried out with a team of 15 painters directed by Breitz, over the period 2018 to 2020, so it overlapped with the lockdown necessitated by the coronavirus. That prevented her usual mode of working, and fits with both the sense of time suspended and the importance of narrative during constraint. The year 2020 was, for many, a time of reading books and watching films. The installation consists of 40 blocks of 25 films, imitating the shelving arrangements typical of video hire shops, plus the 1,001st title shown separately—socially distanced, if you will. That last verb is “Crown” (taken from the VHS cover for The Thomas Crown Affair, 1968). “Crown” translates in Spanish as “corona.” “As the pandemic deepened,” says Breitz, “I found myself identifying with the videocassettes cooped up in Digest. I started to think of the suspended condition of these little plastic bodies—their frustrated potential—as analogous to our own condition.” That cooping up is also consistent with reading the paintings as memorial plaques. “Each painting is a small coffin of sorts,” she said, “in the sense that each becomes the final resting place for the analogue tape that is interred within it.” And many of the verbs concern death, evoking the end of all stories as well as of VHS.

Candice Breitz, Digest, 2020, 1,001-channel video installation, 200 wooden shelves, 1,001 videotapes in polypropylene sleeves, paper, acrylic paint; shelves: 24.4 x 100 x 7.5 centimetres, tapes: 20.3 x 12 x 2.7 centimetres. Installation view, Akademie der Künste, Berlin, 2021. Photo: Stephanie Steinkopf/ Ostkreuz. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, London and New York. Digest was produced with support from the Sharjah Art Foundation + Akademie der Künste, Berlin.

The boxes featuring the other verbs carry the potential to be arranged in various ways, analogous to editing a film. Breitz has stated that she would like any future displays to be “written” by someone else, rather than repeating her own arrangement. Rejecting the more methodical alphabetic or chronological options, Breitz’s version works with 20 thematic groupings, akin to the genre categorizations found on video store shelves. So, for example, there are sets suggesting bodily trauma (“reek,” “rot,” “thirst,” “bleed”), luring the audience (“jest,” “kid,” “charm,” “bewitch”) and replication (“clone,” “mirror,” “spawn” and “double”—that last is the only verb to appear twice). This sets up the potential, having suppressed the narratives intended by the films’ makers, for alternative stories. It also allows the associated abstractions— monochrome, but variably textured— to be read as evocative: that swelling shape might be an emerging “howl,” a tongue could be suggested on “lick”…

It’s easy to be drawn into such details, and that speaks to the obsessive aspect of applying a handmade aesthetic to so many serial objects—encapsulated by the fact that they are painted on both sides, though only the front is visible. This is nothing new in Breitz’s work: think of the task of watching, extracting and recombining dialogue from 28 films featuring Meryl Streep to make Her in 2005. And there’s no shortage of obsession, repetition and burial in art history: the incarceration of Manzoni’s Merda d’artista, 1961; Marcel Broodthaers burying his poetry in the concrete of Pense-Bête, 1964; On Kawara’s Date Paintings, 1966–2014; Allan McCollum’s Surrogate Paintings, 1978, ongoing; and Richard Serra’s Verb List, 1967–68, are all summoned by Digest. More broadly, Breitz can be read as combining how both pop— showily—and minimalism—more austerely—deal with the industrialization of making. Come to that, there is also a tradition of using VHS tape or its boxes as art materials, most notably perhaps Žilvinas Kempinas’s sculptures and the 50-odd iterations since 2002 of Joep van Liefland’s Video Palace. There’s an extra Broodthaers connection in the inclusion of Kentia palms in the installation—though Breitz says that’s because of their frequent presence in late ’80s South African video stores.

Categorizing Digest itself, you might opt for sculpture or painting, but Breitz refers to it as a “1001- channel video installation,” teasingly countering those who think she has departed from her established form. That might lead you to read the individual units as small monitors set out in vertically hung grids—an extreme version of Breitz’s typical means of display. It is also relevant that the works that brought Breitz’s production to the fore consider how mass media such as television, cinema and music shape our response to them. For example, she herself slips awkwardly into the characters of seven popular Hollywood actresses in Becoming, 2003, exposing the limitations and inherent sexism of the female roles she reperforms.

Candice Breitz, Digest (detail), 2020, videotape in polypropylene sleeve, paper, acrylic paint, 20.3 x 12 x 2.7 centimetres. Photo: Saverio Cantoni. Courtesy Marian Goodman, London.

Video on cassettes helped form Breitz, in apartheid South Africa, in “a country that was subject to stringent cultural boycott,” where well-stocked video rental stores “were something of an oasis.” It also allowed consumers to intervene in the viewing experience for the first time, rewinding, fast forwarding, pausing and recording. For those who “did not have the resources to work at the lofty level of film,” says Breitz, “analogue video revolutionized the moving image field.” Less positively, the birth of videotape can also be seen as the first step towards the erosion of the collective viewing experience that had been characteristic of cinema. “In setting the moving image on a path to a virtual future,” she said, “video predicted the profound disembodiment that the digital era would bring to the public sphere.” So Digest’s consideration of the impact of formats on both the creation and reception of content is fully relevant to her work as a whole. And that may explain why she hones in on verbs: it’s as if the films are commanding us how to be. Or commanding her. Digest could be seen as a self-portrait—an account of the medium that helped form Breitz’s own identity, incorporating many of the specific films that she later went on to sample. ❚

Digest was exhibited at the Goodman Gallery, London, from November 24, 2021, to January 20, 2022.

Paul Carey-Kent is a freelance art writer and curator based in the New Forest, England. Go to his Instagram @paulcareykent to find out more.