Bonavista Biennial

Twenty-six installations in 14 communities over one weekend—the 2021 Bonavista Biennale was overwhelming for someone who’d grown accustomed to near solitude. It was like Christmas morning a dozen times a day. I burned energy as fast as my car burned gas, and my experience of the festival is still difficult to summarize.

This year’s curatorial theme was “The Tonic of Wilderness”—a phrase from Henry David Thoreau’s account of his time living on Walden Pond in 1854. I turned this idea over and over as I travelled each kilometre of the festival route.

Wilderness is a problematic concept, with its connotations of empty, unpeopled land. It is especially problematic on the Bonavista Peninsula. While beautiful, this unceded Mi’kmaq territory is a major tourist draw and has been inhabited by Indigenous peoples for millennia. It is also recorded as the first landing site, in 1497, of early modern European colonizers, including John Cabot, on the coast of North America.

Installation view, “Regeneration / Piguttaugiallavalliajuk / Ussanitauten—Seven Northern Labrador Photographers,” 2021, Bonavista Peninsula, Newfoundland and Labrador. Left to right: Samantha Jacque, On Top of the Mountain, 2020, Nikon D5300, giclee print in latex inks on polyester textile with blackout back, 121.9 x 182.8 centimetres. Eldred Allen, Scull of Harp Seals, 2020, giclee print in latex inks on polyester textile with blackout back, 182.88 x 139.72 centimetres. Gary Andersen, Out to the Ice Edge, 2020, giclee print in latex inks on polyester textile with blackout back, 121.9 x 182.8 centimetres. Photo: Brian Ricks.

Wayne Broomfield, Nature’s Curves, 2015, giclee print in latex inks on polyester textile with blackout back, 223.5 x 152.4 centimetres. Photo: Brian Ricks.

In addition, memes like “Thoreau’s mother did his laundry” have been circulating recently, positing that the writer was not isolated in the wilderness while he wrote Walden but enjoyed support from nearby family and friends. Researchers and writers like Rebecca Solnit have written that Thoreau never claimed the hermit-like status his story has gained over the years, and that the reality of his domestic chores was likely complicated and collaborative.

What the theme did do was act as a catalyst to consider some of the privileges that allowed viewers to experience the Biennale at all. Newfoundland and Labrador has been less affected by the COVID-19 pandemic than most places in the world. Our island geography has protected us, at least somewhat. This context allowed curators Patricia Grattan and Matthew Hills the opportunity, and challenge, to plan a non-virtual festival. Audiences were able to gather and experience new art in person, amid stunning landscapes. There was no public reception but plenty of small, invaluable meetings on beaches and roadsides, and in buildings across the region.

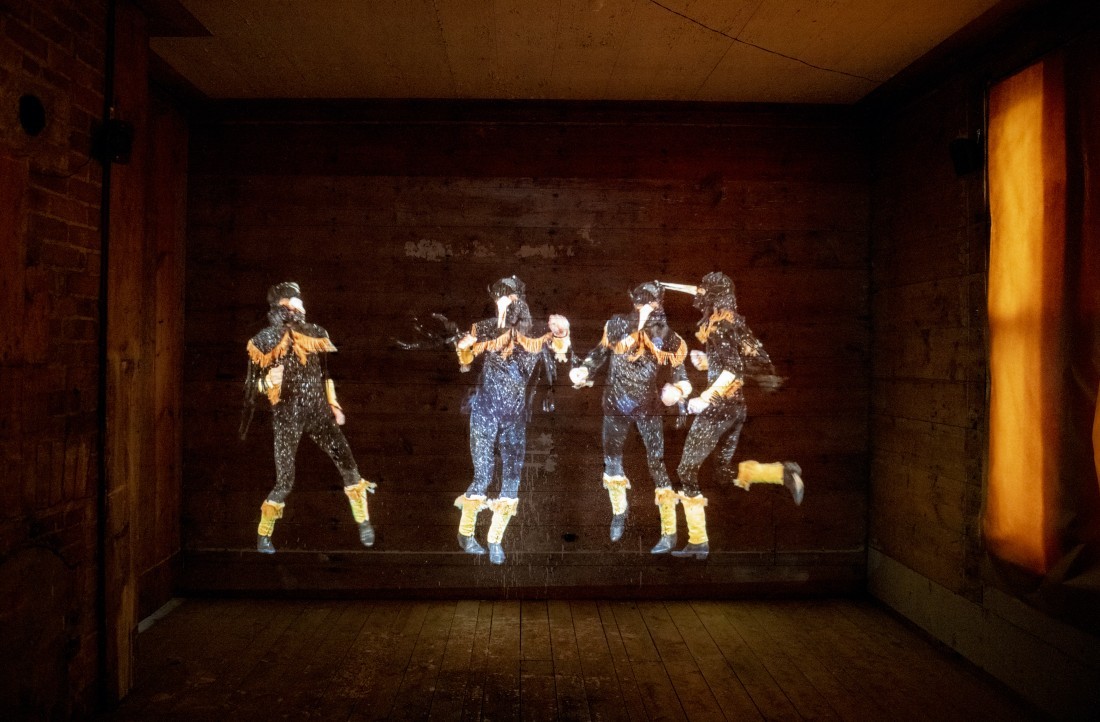

The first project I encountered was Graeme Patterson’s multichannel video projection, Ghosts of a Gathering. When I closed the door of the disused house against daylight, strange, life-size figures emerged in the far reaches of dark rooms. Plague doctor, disco queen or Hollywood cowboy—the same beak-masked, sequin-clad figure is multiplied. They all twirl and boogie to a slow, haunting soundtrack. They are the artist himself, dancing alone, in front of the camera. It borrows the format of many an early-lockdown experiment, when artists recorded and superimposed their own performances in lieu of face-to-face collaboration. But this is more considered and more reflective of long-term isolation. Mournful, frenetic, anxious and joyful at the same time.

Graeme Patterson, Ghosts of a Gathering, 2021, video loop with soundtrack. Photo: Brian Ricks.

The soundtrack shifts to something upbeat, more in keeping with the dancer’s movement. You start to think you might let go of this pervasive tension. Maybe you could dance with other people— even strangers—like you did before. The soundtrack shifts again—each cock of the hip accompanies a heavy drumbeat. It’s not sad but deliberate. Patterson has managed to puncture something here. Perhaps it’s the bubble I’ve been inhabiting. Suddenly there seem to be possibilities to explore.

The furthest community on the Biennale map is Red Cliff, where Jessica Winters has curated what is identified as a special project but as part of the festival. Seven northern Labrador photographers were asked to reflect on “humans’ relationships to ‘wildness.’” “Regeneration | Piguttaugiallavalliajuk | Ussanitauten” deserves a review in itself, and included artists Jennie Williams, Wayne Broomfield, Holly Andersen, Eldred Allen, Samantha Jacque, Gary Andersen and Melissa Tremblett. Images range from vast landscapes and drone views of harp seals in the water, to people preparing food. Installed inside and outside Quinton Premises—a former working building complete with a fish oil press and vintage pop bottles—the project raises multiple questions about colonial exploitation of human and natural resources and strategies for a sustainable future.

Logan MacDonald, Bodies on the Beach, 2021, mixed media. Photo: Brian Ricks. Commissioned by Bonavista Biennale.

It is vital to state that one of the most significant projects of the Biennale is missing. Logan MacDonald had planned an installation in conversation with the bronze statue of John Cabot at Cape Bonavista. According to an interview with CBC Radio, MacDonald had intended to cover the statue safely in mulch—a reference to the trees that once covered the island and were harvested for ships’ masts and building material. It was also a way of questioning which histories are celebrated. Permission for the project was withdrawn by the town of Bonavista about five weeks before the festival. Mayor John Norman’s statement on the matter cited planned maintenance for the park surrounding the statue and concerns that the project might represent something negative.

MacDonald’s alternative project, Bodies on the Beach, is highly visible along a 1.5-kilometre windbreak that separates Bonavista from the water. Large-scale words and phrases in English and Beothuk are spelled out against the sky. Some of the English text is taken from Cabot’s accounts of Newfoundland. The Beothuk is from word lists that record a smattering of the language that was decimated after first contact. Words alternate backwards from one side and forward from the other, urging viewers to trek around the barrier to gain a better understanding.

Marcia Huyer, strata, 2021, mural on two sides of house, exterior house paint, 8 x 4.5 metres and 4.25 x 4.5 metres. Photo: Stephen Zeifman.

So many projects offer narratives to consider how we live with each other and the resources we have. Jerry Ropson’s video projection and artifacts, Preface for a liturgy (blood ledger), at the Loyal Orange Lodge is like a glimpse of an epic novel. Generations of boys play pretend in the woods, and generations of men construct their authority over them, and a community around them, with hammers and saws. Marcia Huyer exposes and enlarges domestic histories by hand-painting torn layers of wallpaper across the clapboard of a closed house in Duntara. Seafoam, a site-specific audio piece by Sara Tilley, had me rooted to a cliff in the rain, listening to the story of a grandmother who won’t leave her rural house but won’t waste money repairing it either. Far below, waves crash over the spot where Will Gill’s Green Chair sculpture was anchored during the 2017 Biennale, before ice swept it out to sea.

Organizing a festival during a pandemic must have been a massive logistical feat, but the experience of it almost allowed me to forget that. Instead, it was a reminder to savour the thoughtful, challenging opportunities on offer. ❚

“Bonavista Biennale” was exhibited on the Bonavista Peninsula, Newfoundland and Labrador, from August 14, 2021, to September 12, 2021.

Jennifer McVeigh is a writer and editor living in St. John’s, Newfoundland.