Barry Schwabsky’s PictureLibrary: Bodies and the How of Seeing

Hester Scheurwater and Lina Scheynius

__1100_825_90.jpeg)

Hester Scheurwater, Shooting Back, published by Gerber & Keller Zurich, 2011, edition of 250.

The Dutch artist Hester Scheurwater published her first book, Shooting Back, a decade ago. Lately she has issued a flood of publications, but if the rhythm of her work’s appearance has changed, her project remains consistent. As she described it then, her work concerned “this border between private and public. In trying to reach this frontier,” she continued, “I make use of my own body and present fantasy self-images.” In fact, she was an early adopter of social media as a conduit or site for art practice. Shooting Back (Gerber & Keller, Zurich, 2011) was a compilation of “selfies,” iPhone and other digital images (both black and white and colour) using graininess, glare, inconsistent resolution, exaggerated perspectives and other distorting effects to craft images of impressive intensity—an intensity that only increased as they crowded up against each other at the notably larger than cell phone-sized scale of the book. This phase of Scheurwater’s work also resulted in a book of highly unusual construction, All I Ever Wanted (Éditions Bessard, Paris, 2015, edition of 500). In both books, the fiery, dynamic and fragmented images felt absolutely imbued with subjectivity, but it was impossible not to ask oneself: Whose? As the publisher Walter Keller wrote in a “Letter to the Viewer” that functioned as an afterword to Shooting Back, one could hardly imagine “that the real Hester Scheurwater and the ‘persona’ … in these photographs are one—they might actually be completely detached from one another.” Completely, really? No, but detached enough for the artist to glimpse herself as an object. Was the subjective aura of the images, then, a pure product of the machine itself, of the technology and conventions of seeing that govern the space in which images are encountered? If the answer was ambiguous, that’s because Scheurwater’s concern was to explore that space, and to mess with it, rather than to define it.

In 2020, Scheurwater self-published a group of four small booklets, each in an edition of 100. These were her first published images using models other than herself. Red-haired Noemi poses in a nondescript room with bare walls, drawn blinds and a few random furnishings—a couple of ladders, a folding table sometimes covered with a white cloth. Her stance is confrontational, at times domineering. She owns her nakedness. The protagonist of Annabel is seen in a fluorescent-lit painter’s studio crowded with canvases and a well-stocked bookcase; dressed in black socks, she seems more self-contained than Noemi, yet her poses are more awkward, off-balance; her presence is subtle, elusive and more controlled than it might at first have seemed. A third booklet is titled A.; apparently this model did not want her name used, and neither do we glimpse her face. Her environment: a comfortable living room filled with potted plants and notably lots of natural light from big windows barely guarded by sheer, almost transparent curtains—a different, more porous relation between inside and outside than in the other two sets of images. Name and face aside, A. is perhaps the most self-revealing of the three young women—but she reveals herself as a body more than as a person. She is comfortable enough with her appearance neither to dramatize it nor to necessarily identify with it. The fourth booklet in the series, Sincerely Not Yours, incorporates a few images from each of the other three as well as shots of other women, including—as we recognize from earlier work—the artist herself, though now seen in a surprisingly different way from in the past: as an embodiment of the grotesque. The title, also that of a 2020 exhibition at Frank Taal Galerie in Rotterdam, suggests Scheurwater’s scathingly ambiguous sense of the charged space between public and private.

Hester Scheurwater, Ego Trip, self-published softcover book, 2021, edition of 250.

The books Scheurwater has published most recently present a further look at the imagery in some of her books from last year. Pose is a deeper dive into the session with Annabel, its unnumbered pages presenting what I’d estimate as about 160 black and white images. Most are vertically oriented and (even more than those in A.) contained by white borders, but some are horizontal shots presented as double-page spreads with the images bleeding to the edges of the page. In the latter, the loss of part of the picture to the gutter seems a deliberate strategy, a way of claiming part of the body, despite everything, as a terrain of privacy. By contrast, many of the vertical compositions seem to take a more clinical stance toward the subject; and the big shadows thrown by low-positioned lights on the studio’s wall and ceiling seem to loom threateningly over the scene—I thought at times of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. In two more new publications, Scheurwater returns to herself as the subject of her own gaze, and indeed one of them is titled, simply, Hester Scheurwater. In many of its colour images, she seems to be squeezing her lubricated face and body toward the lens, squeezing herself together in such a way as to exaggerate every form. How did she give herself that enormous double chin? If the Hester Scheurwater of 10 years ago flirted both with the imagined viewer and with the clichés of erotica, today she dares the viewer to see her as monstrous and to turn away. And yet the blatant sensualism of her self-presentation and the sense of her as too close to avoid make turning away impossible. In the third of her new books, Ego Trip, she juxtaposes newer and older self-portraits, along with some pictures that are self-evidently far from self-portraits—some close-ups of a penis, for instance, or what appear to be video stills of a performer, of indeterminate gender, in mime’s makeup—to convey a sense of self as far too various to accord with any stable **identification.

_1100_750_90.jpg)

Hester Scheurwater, Ego Trip, self-published softcover book, 2021, edition of 250.

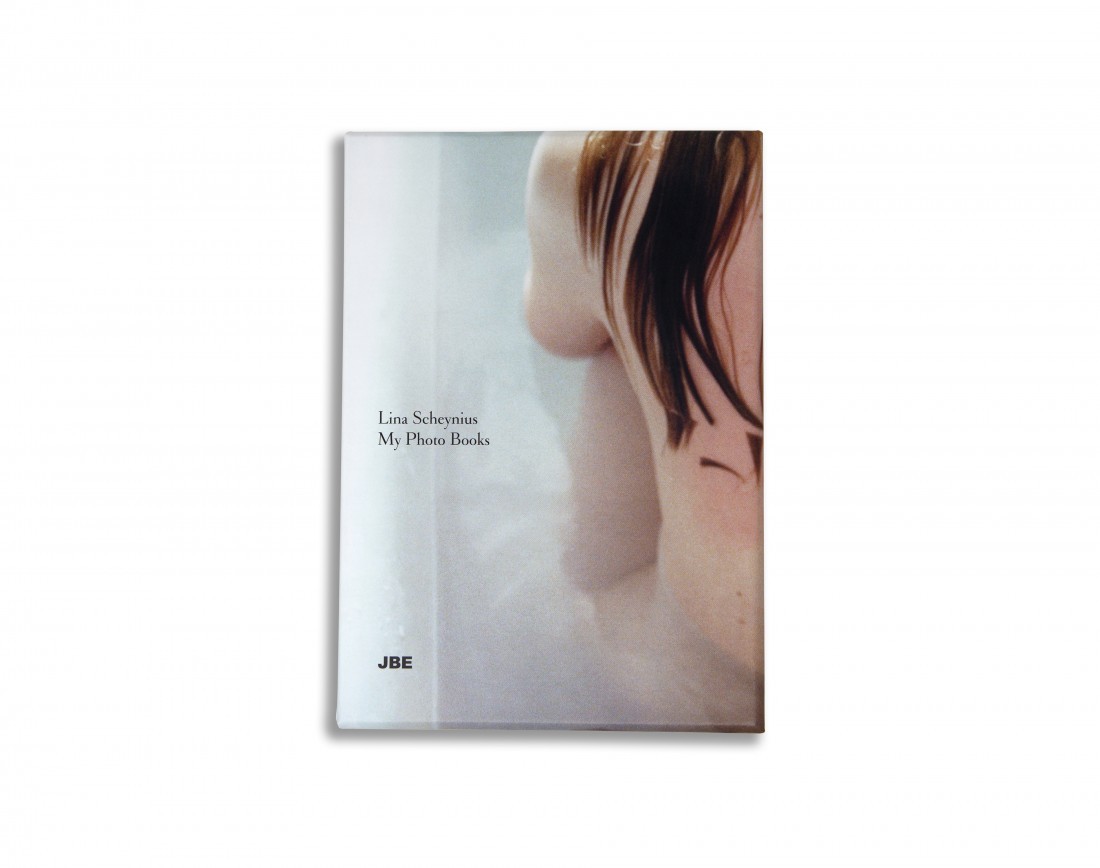

Another artist whose work took root in the online realm is Lina Scheynius, a Swedish photographer based in London, whose images were first seen on Flickr—then Tumblr, Instagram and now Substack. “I really like that online nothing is permanent,” she once said, and yet since 2008 she has been preserving her work in a series of small, self-published books, numbered rather than titled, and for now amounting to 11; these were recently republished as My Photo Books (Jean Boîte Éditions, Paris, 2019), a boxed set in an edition of 1,000.

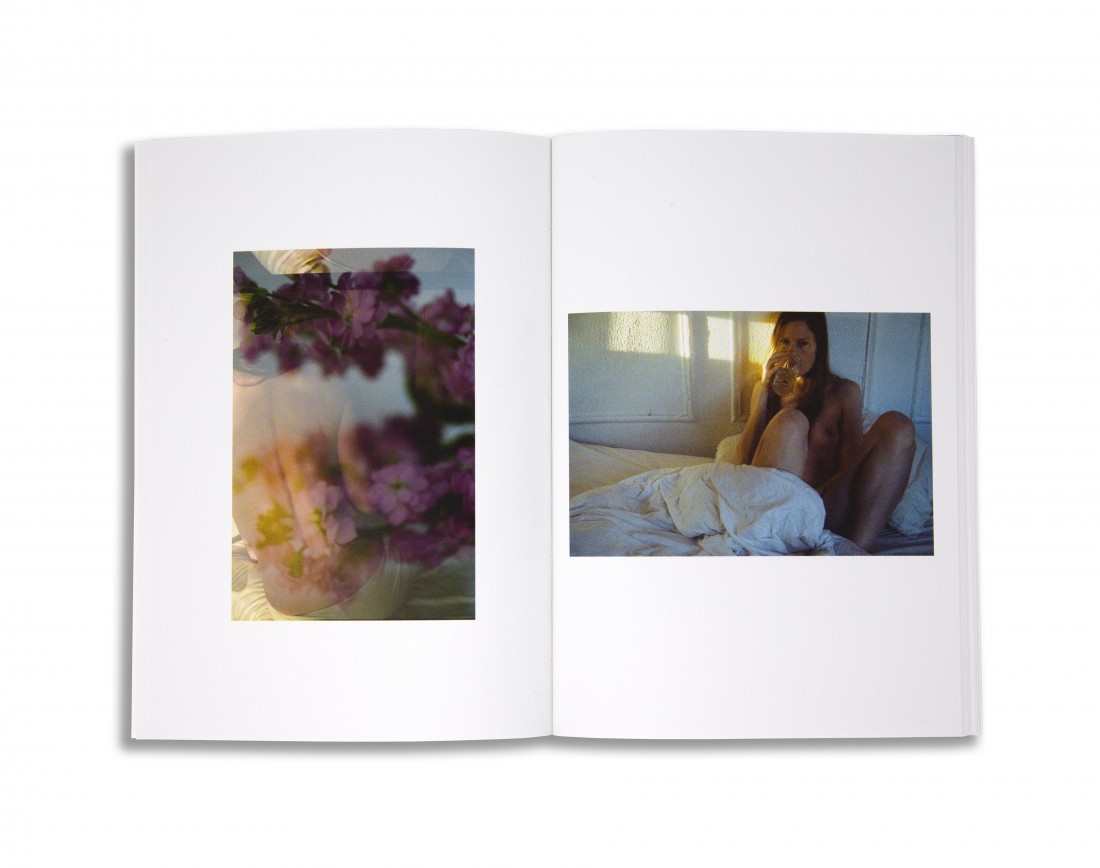

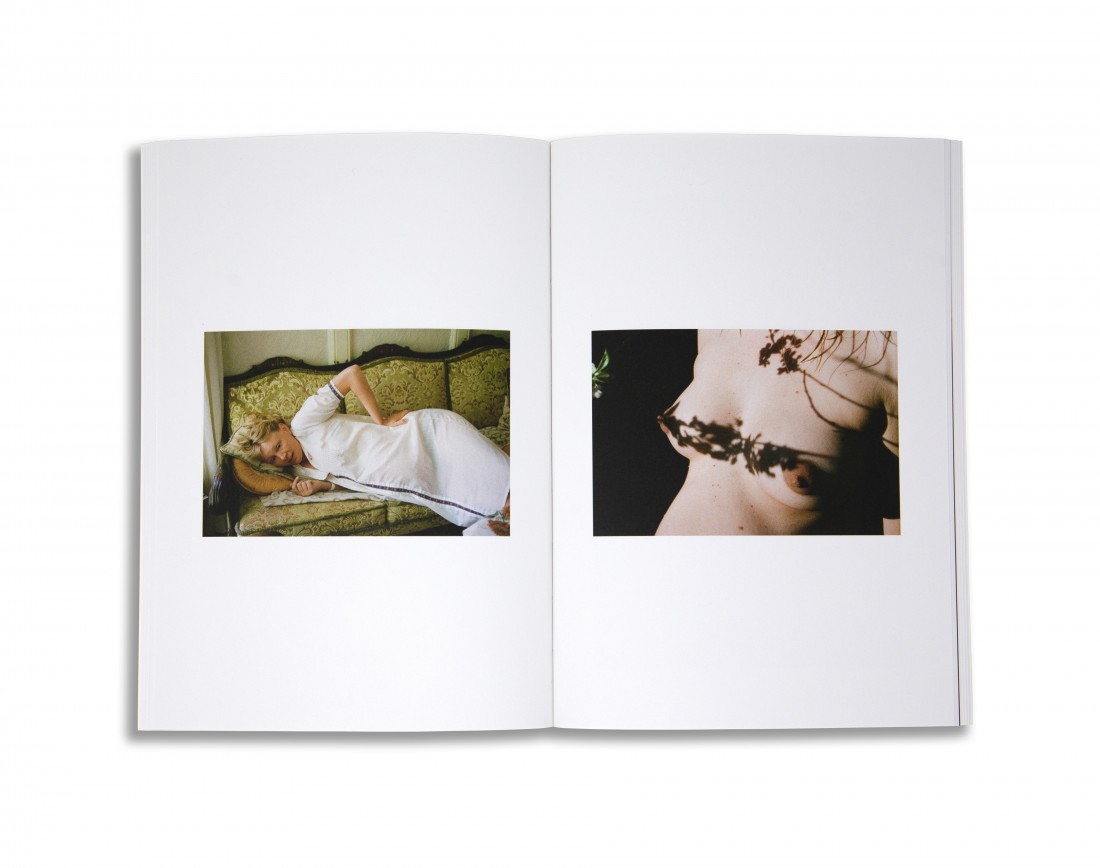

In contrast to Scheurwater’s overriding propensity toward brazen confrontation, Scheynius cultivates an aesthetic that is sidelong and elusive even in showing the naked body—the artist’s own or that of others. The thread that runs through this nearly 15-year-long project is an assumption of intimacy. Or rather, I should say the “fiction” of intimacy, for the viewer remains, after all, a voyeur who, much as he or she may enter into the mood so elegantly conjured by the artist, remains a stranger to the nitty-gritty details. With their pale, washed-out colours—or soft, low-contrast tones in the case of those that are monochromatic—these glancing images often seem to use light as a veil intervening between the viewer and the subject, or, on the contrary, as a luminous haze that envelops both the gaze and what it seeks out but in either case emphasizing atmosphere over fact. Scheynius is not documenting her life, it seems, so much as already recollecting it in the very present in which it is lived.

Just as separate images find a fuller life when gathered as a book, where they reveal a more complex relation to time, Scheynius’s books become richer when encompassed into a set of greater scope. The apparent self-containment promised by binding and blank white covers becomes porous. Life is lived backwards and forwards alike. While some of the books represent a single concentrated period of work—number 11, for instance, was shot entirely in May 2018; number 7 encompasses the summer of 2014—most collect images taken over a period of years. The colophon of book 3, published in 2011, says it contains “photographs taken between 1991 and 2006.” But in 1991 Scheynius would have been 10 years old. Can any of these pictures really have been taken by a small child? I’ll hazard a guess: the one that shows mostly a white ceiling and, at the bottom, the upper part of a girl’s head (eyes and blonde hair); maybe this is the work of a kid trying unsuccessfully to figure out how to hold the camera in such a way as to take a self-portrait? If so, it was a lucky miss, _felix culp_a, for the skewed perspective and subtly charged blankness of the picture, animated by the searching eyes at the bottom of the frame, anticipate the essence of the artist’s mature aesthetic.

What is personal to these pictures, and at times disconcerting, is not what is shown but what is seen, or, rather, how. But the question is often, How was it seen? In the most intimate moment between two people there is a third party, the camera. Consider an image about a third of the way through volume 6, a view looking down at the space between two people in intimate relations yet at a distance, their bodies barely touching: on the left, the naked man, his erect penis grasped by the woman in pink panties on the right, her legs spread wide around his; her nipple appearing at the edge of the frame. Her left arm reaches back behind him. So she is not holding the camera. He could be—his arms and hands are not visible—but more likely the apparatus has been positioned on a tripod near them in a sort of cyborgian ménage à trois. But imagine what would be involved in staging one’s sexual relation (we politely dismiss Jacques Lacan’s assertion that there is none) in such a way as to compose this beautiful and poignant image—what discipline, what artifice. Sexual being is at the core of their concern yet exposure is not the aim; a certain deflection of the gaze might seem almost demure were it not for the emotional vulnerability risked in trying to see oneself as seen by others. ❚

Lina Scheynius, My Photo Books, published by JBE Books, 2019.

Lina Scheynius, My Photo Books, published by JBE Books, 2019.

Lina Scheynius, My Photo Books, published by JBE Books, 2019.

Lina Scheynius, My Photo Books, published by JBE Books, 2019.

Barry Schwabsky’s recent publications include a monograph, Gillian Carnegie (London: Lund Humphries, 2020), and the catalogue for the retrospective exhibition Jeff Wall (Potomac, Maryland: Glenstone Museum, 2021). His new collection of poetry, Feelings of And, is forthcoming from Black Square Editions, New York, 2022.