Bee Work: Aganetha Dyck’s Project in Progress

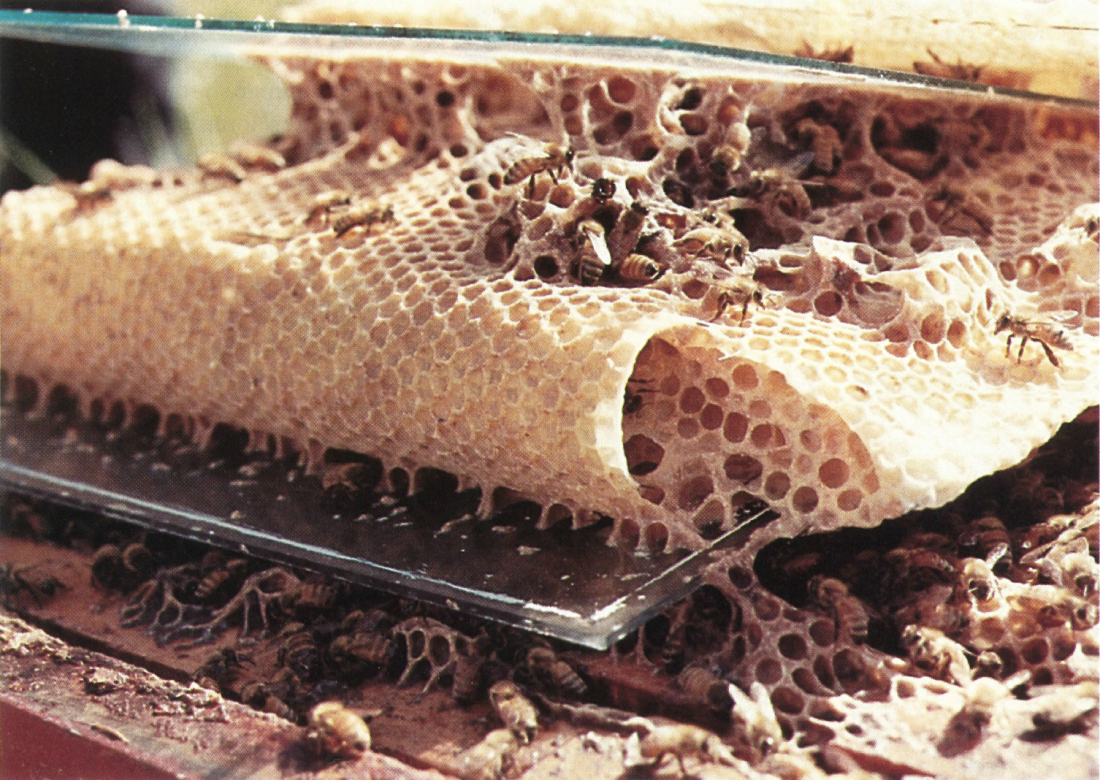

Photograph: Peter Dyck, 1991.

It’s the daily, the domestic that’s been woman’s domain—kitchens, keys and the keeping of things. Aganetha Dyck has taken it as her task to elevate the small, intimate particulars, the obvious, homely artefacts, and make us see them fresh. From her earliest work—shrinking and felting discarded woollen clothing, having the pieces stand in for a miniature army of absent souls marching to glory rag-tag across a gallery floor—to her glass quart sealer jars of deep-fried and preserved dress-button exotica filling fabricated larder shelves, she’s elevated the ordinary, attributing miraculous value to the simplest objects, turning the quotidian to magic. Rumplestiltskin as art-maker, the secret being her fine and generous gaze.

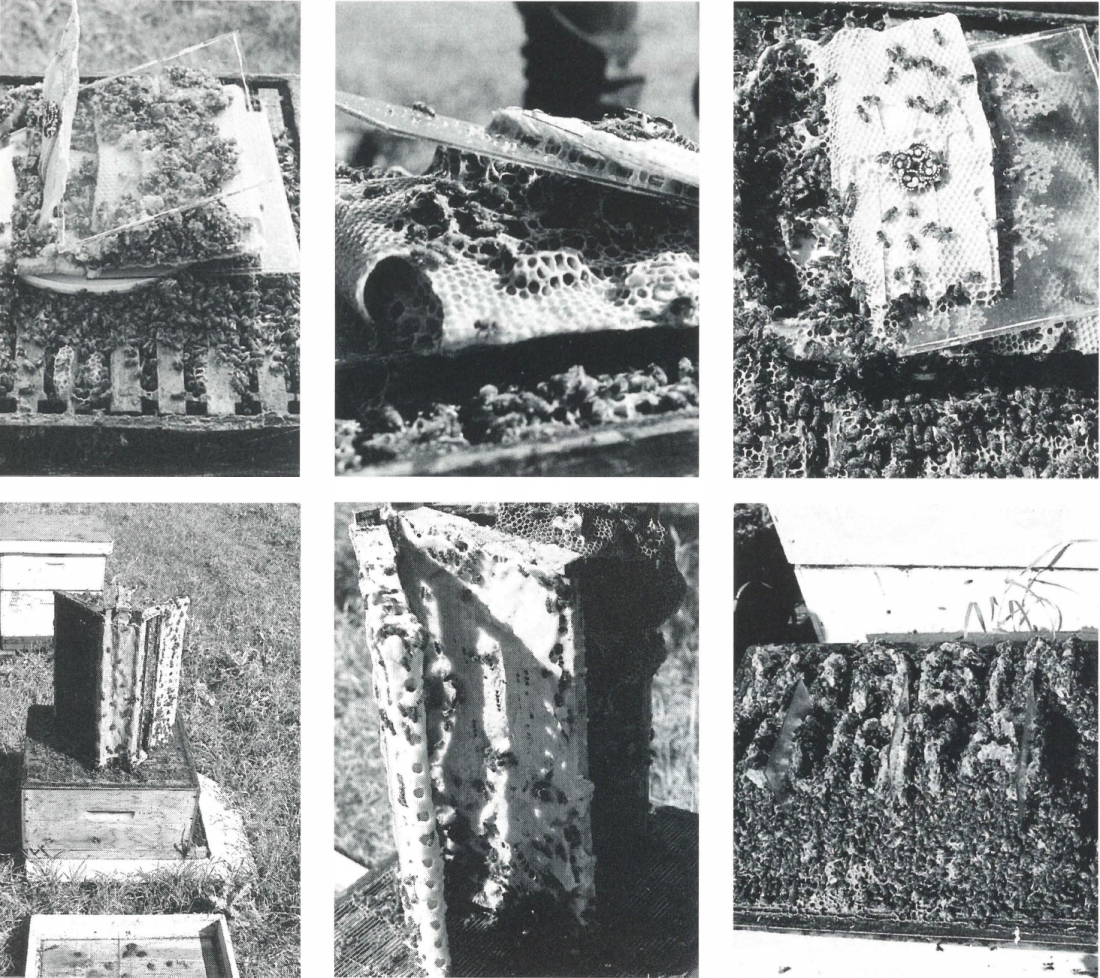

Photographs courtesy Aganetha Dyck.

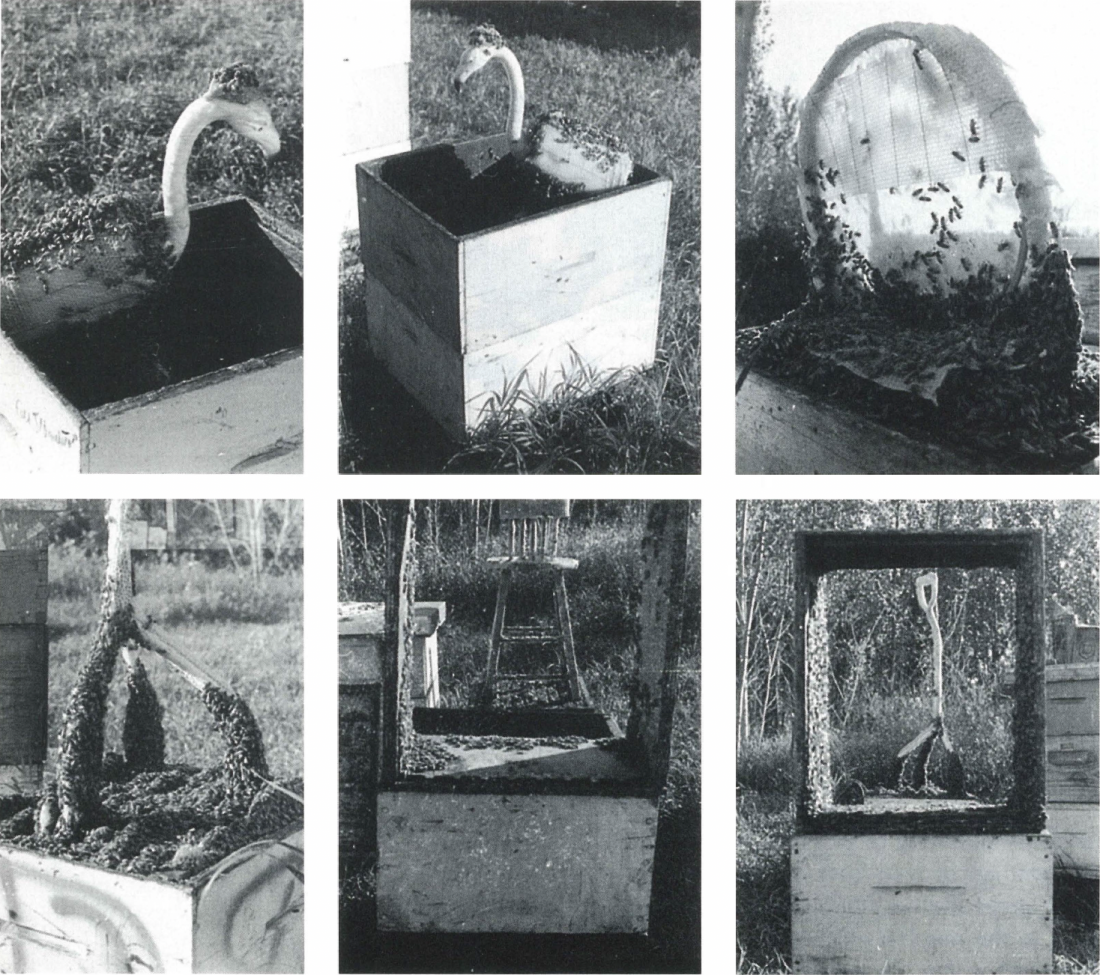

Now she’s looking in another direction. She’s turned her attention to the prototypical industrialist—the honey bee. She’s enlisted bees, hive after hive, as collaborators and she has them making art. The art is still very much a work-in-progress and this summer she began providing them with new forms on which to build their combs. So instead of rectangular wooden frames covered with redolent, hexagonal wax chambers, the bees are working on rudimentary book forms with pages made of wood, cotton doilies and glass. Or they’re dressing the head and body of a plastic flamingo; covering the handle and stem of a walker; resurfacing a wooden chair; transforming a conical road marker into a fantastic wax tower.

Photographs courtesy Aganetha Dyck.

There’s a transitional piece that combines two bodies of work—books and purses—and it becomes a book with a handle and brooch. And there’s her celestial book work. Here Aganetha Dyck has given the bees small wooden letters which read “Virgin Journal.” “They’re working a text,” she says, covering the letters in wax comb. In her reading she’s discovered that until early in the 20th century it was believed that all bees’ were virgin births. Because of this divine link, their wax was used to make church candles, no doubt their burning an inadvertent transliteration of heaven-scent.

In a happy mix of humility and artfulness, Aganetha Dyck offers props for the bees’ own technology, turning it with her intelligence to a sum greater than its small humming parts. ♦

Meeka Walsh