“Barns of Western Canada” and “Prairie Giants”

I suppose if you asked visitors to the prairies what forms stood out most in their memories, they would tell you, after they commented on the fact that they were rather more inclined not to have noticed anything at all, that they remembered clouds, grain elevators and barns. I don’t know of a book on clouds (although prairie painters as different as Illingworth Kerr and Dorothy Knowles have made these aggregations of filmy moisture into very substantial structures in their art) but there are now separate books on the two most noticeable man-made forms that punctuate the vast prairie landscape. Robert Hainstock’s Barns of Western Canada and Hans Dommasch’s Prairie Giants are valuable, if eccentric, looks at the intersections between the history of folk architecture, aesthetics and contemporary myth-making.

The most obvious thing one can say about barns and elevators is that the motivation behind their design was exclusively utilitarian, and both books take as their point of departure this uninspiring but inescapable fact. But what’s interesting is how both “compilers” deal with the common origins of their architectural subjects. Hainstock is a journalist and editor, and his is a no-nonsense book that tells you everything you’ve always wanted to know about barns but had no intention of asking; Dommasch is a practising photographer and art historian, whose concern is to go beyond function to art and, finally, to a kind of architectural mythology. As he writes in his preface, “all of a sudden these utilitarian structures took on a new meaning for me. I began to see them as skyscrapers, sentinels, monuments—prairie giants.” There is something of Hans-on-the-road-to-a-flatland-Damascus here, and, in fact, Dommasch’s text takes on the rhapsodizing texture of conversion to the church of the Latter Day Romantic Grain Elevator.

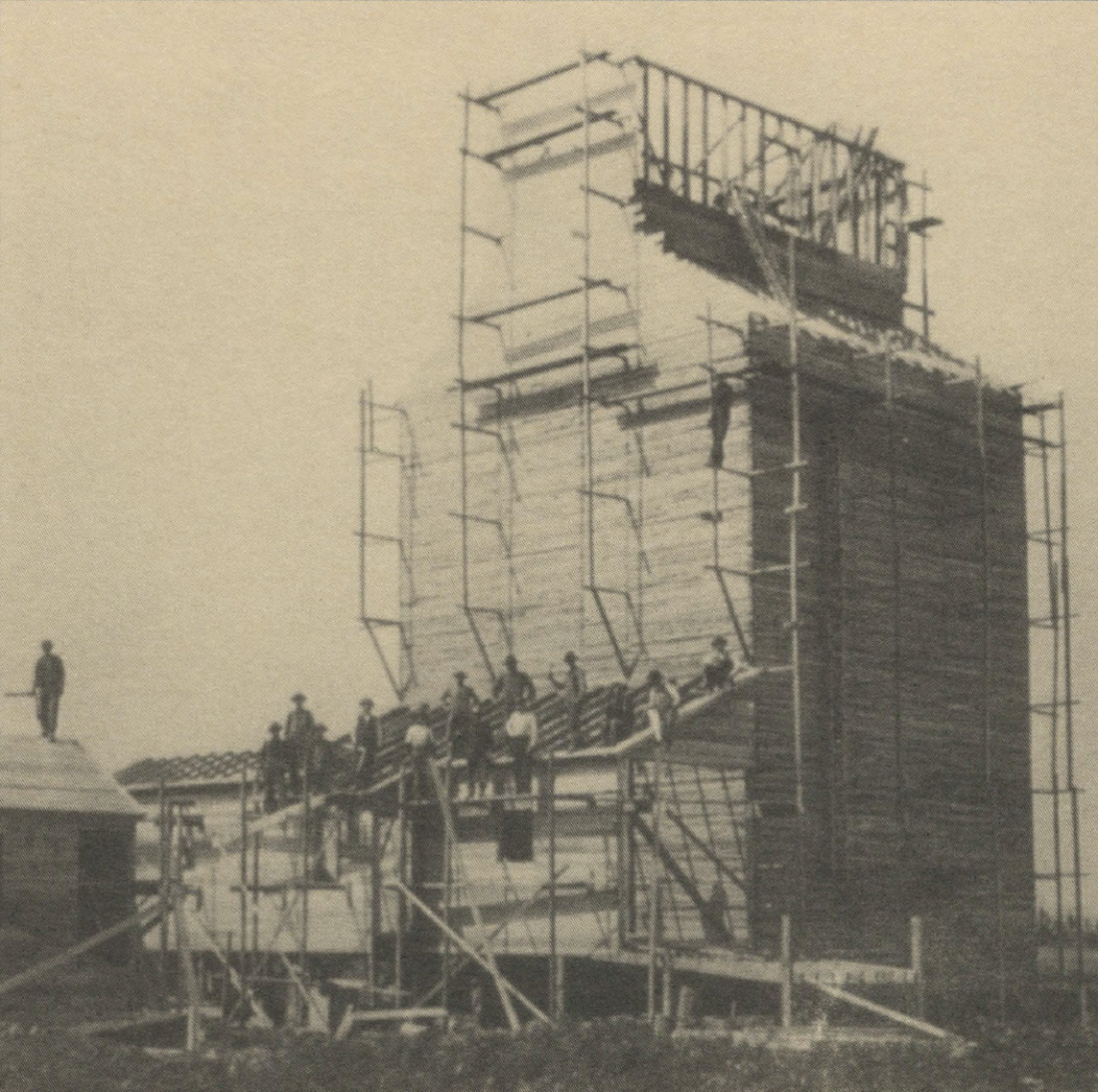

Photograph Glenbow Archives

Hainstock, on the other hand, waxes positively dull. In giving us an extensive history of English, European and North-American barns—a word, incidentally, which means “barley place”—he avoids metaphors as if they were a plague of grasshoppers. Early in the book he tells us that “The British Farmer was caught between the dung-pile and a hard place” and while I’d settle for the latter, Mr. Hainstock offers no preference. Much later in the book, in one of the many useful photographic captions, he describes the gigantic dairy barns around Delta, B.C. as being “just a cream can’s throw from the Pacific Ocean.” Having been born and raised in Manitoba, his humour clearly has taken on the contours of prairie space. These two tropes, by the way, are the only two I could locate in the book.

Hainstock’s purpose is not to demonstrate his own wit but to pass on information and, in an undemonstrable way, to communicate his quiet passion for the subject. At the very beginning of the book, he approvingly quotes a Wisconsin writer on the simple value barns have for prairie dwellers. “The old barns are of the people, the common people who live on the land, and their preservation is for the people, all of the people. Everyone has roots that trace back to the land. And the old barns are of the land.” There remains a problem with the language here; this passage sounds like it was co-written by the authors of the book of Genesis and the American Declaration of Barnyard Independence. But the purpose is clear: Hainstock himself calls barns “architectural storybooks” and the story he’s telling is one of traceable loss. There are currently 200,000 barns in Western Canada but they are quickly disappearing as farm practices change. Hainstock, who is frustrated by what he calls “the inertia that inhabits restoration and preservation,” is not simply writing a history; he is issuing a plea, a warning and perhaps an elegy for a way of life embodied in these remarkable and various structures. “The love that we give to the romantic barn,” and here Hainstock is quoting another writer, “is given to a departed spirit whose image lingers on.” One of the obvious services his book performs is to document the lingering forms these architectural spirits have assumed.

Elcon, Saskatchewan, photograph Stewart Klyne

Not surprisingly, Hainstock’s photographs—and there are 226 of them, in black and white and colour—are straightforward and clear with little attempt at aestheticization, although occasionally the images do fall into the generic category of “the prairie picturesque.” His text is equally uncluttered and full of fascinating bits of information: about the origins and number (there are 100) of Mennonite housebarn combinations in Manitoba and Saskatchewan; about the rise and fall of barn-building bees; about rarities—like the fossilized shellfish barn near Lethbridge, or the 20 circular barns throughout the prairie provinces built by religious men who saw in this circle shape both perfection and the utility of keeping “the devil from hiding in corners”; and about the reasons why barns were primarily painted either red or white. There are also some short explosive stories about the demise of barn-builders who tempted fate or the CPR. In 1905 a Saskatchewan farmer built a huge, two-level circular barn with 4800 square feet on the upper level, supported by massive posts. Five years later, while discussing his share of the crop being loaded into bins above him, the floor collapsed and Mr. Howie was buried in a terminal avalanche of barley. No less ironic was the fate of Louis Perry, an enterprising farmer who decided he needed a more substantial floor for his barn, the material for which he “borrowed” from the CPR in the form of rail ties. Mr. Perry spent a month in jail for his innovation and later was killed by a team of runaway horses. Providential justice, it appears, was considerably rougher than the human kind in the early years of prairie barn-building.

Hainstock recounts these tragedies as directly and with as little embellishment as possible, and his restraint, in these instances, makes the stories all the more poignant. So much of the material in Barns of Western Canada seems like raw material for fiction and other forms of art-making, as if it were the fodder and grain out of which art could grow.

Hans Dommasch is less a recorder than an interpreter of his subject. What he wants to relate in his book is “the story of [his] emotional response to the giants of the prairies” and he effects this through 103 photographs (19 in black and white; the remainder in colour) selected from almost 4000 images. While they were submitted by photographers from across Canada and the US, Dommasch himself has organized them under six categories—”Symbols of the Past,” “Sentinels,” “Symmetry,” “Seasons,” “Skyscapes” and “Cycles of Life”—which, as their titles indicate, address the architectural, symbolic, aesthetic and romantic dimensions of the grain elevator. There is little writing in the book, except for a tidy and informative introduction by Brock W. Silversides, who is unaccountably not mentioned anywhere else in the book, and a gushing preface by Mr. Dommasch. “In these tempests,” he writes, describing winter blizzards,

Sky and land fuse like passionate lovers. Road and town are hidden behind white. But the imposing outline of the elevator looms up from behind the veil of swirling snow, a steady beacon to the traveler in the surrounding chaos.

Springwater, Saskatchewan, photograph Hans Dommasch

It’s writing like this which makes me thankful that Mr. Dommasch is a photographer. And make no mistake about it, he’s a good one. Prairie Giants is really a complete viewer’s guide to the range and mute beauty of this indigenous architectural form and Mr. Dommasch has done an admirable job in serving it up to us in its various forms. The perspectives are legion, including close-ups of elevator clusters in which the images become abstract paintings; “readings” in the semiotics of grain company logos; jewel-like photos of prairie towns in early morning winter light (the two-pager of Prince Albert, Saskatchewan by Mr. Dommasch himself is superb, as is a landscape portrait of Carbon, Alberta by Cameron Ertman). There are other single images that are startling: the phenomenal dwarfing of the elevators by a towering rainbow in Osler, Saskatchewan; the steel monolithic and seemingly impenetrable collection of buildings in Harris, Saskatchewan, which seems entirely to fill up the space; and the lowering clouds above Stavely, Alberta, an architecture of space that is thoroughly intimidating and thoroughly beautiful. Some are evidence of our stupidities as well—the psychedelic P & H elevator is not located in the credits at the end of the book, an omission that I imagine was deliberate.

In his preface Mr. Dommasch remarks that he senses a relationship between country graveyards and country elevators: both are paradoxically memento mori for him and symbols of “the continuity of life in a prairie town.” To emphasize his point he’s chosen one dazzling image of Rosetown in which the community’s graveyard sits in silent shadows in the foreground of the photograph, while at the centre, above the horizon line, a bronzed grain elevator speaks the glories of art and commerce, like a rare palace out of some prairie Byzantium. It is a mesmerizing embodiment of Dommasch’s musings on death and life. Near the end of the book, there is an image of a less attractive kind: three elevators near Claresholm, Alberta are being dismantled. They stand on the prairie with all the poignancy of wounded birds, and the sections that have been removed seem more like amputated limbs or holes in space than they do missing parts of a building. These elevators seem hurt, candidates for tombstone recognition in one of the book’s moody and nocturnal graveyard photographs.

Taken together, these two books offer the reader some intriguing leaps into the present condition of prairie architecture. Barns and elevators are undervalued, victims of their sheer effectiveness and utility. Architectural historian Harold Kalman notes that the elevator is regarded as “the most Canadian of architectural forms”; they are also viewed as “helpful, if unpicturesque structures” and “a bit drab and ugly.” Perhaps we need to recall the pronouncement of Le Corbusier, that buildings like barns and elevators are architectural abstractions that “spiritualize hard fact.” We would be well advised to make an imaginative leap of faith, away from an emphasis on the factual dimensions of our folk architecture, and towards the simplified spirituality which it so clearly contains. These two books, even with their shortcomings, are valuable guides in that necessary adjustment. ♦

Robert Enright is the cultural affairs reporter for CBC’s 24 Hours and the editor of Border Crossings.