Bahar Noorizadeh

Featuring two black-box video installations, Ultima Ratio Δ Mountain of the Sun, 2017, and After Scarcity, 2018, “governance machines and the future of futures” is artist, writer and filmmaker Bahar Noorizadeh’s first solo exhibition in Canada.

Ultima Ratio Δ Mountain of the Sun begins with a question: Will human reason one day be replaced by a machine? Blending three-dimensional models with documentary footage, Noorizadeh inserts manifesto-like text blocks among scenes of hashish production from Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley and fugue-state stumblings through a Roman archaeological site in Baalbek (eastern Lebanon). While Noorizadeh’s opening question is left unanswered, the viewer is left considering the relationship between technology and intoxication, a theme actuated via the second film in the exhibition.

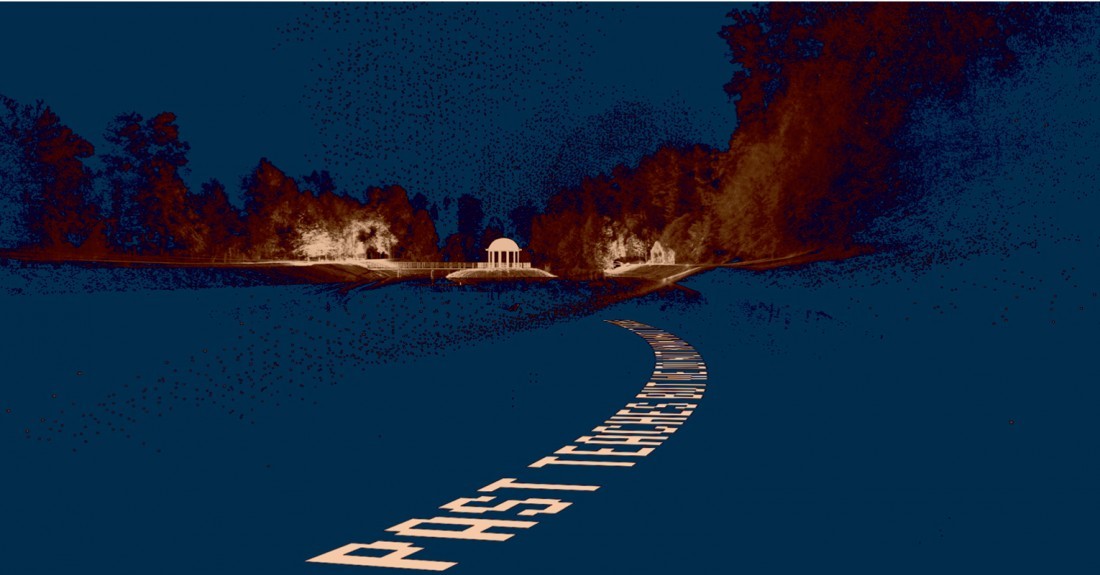

After Scarcity weds a LiDAR-scan officiated tour of Russian architecture with an economic history of the Soviet Union. LiDAR, a scanning method that uses pulsating lasers to measure and map the contours of an object or building, presents the viewer with architectural forms that act as placeholders between flying text and a Russian-language voice-over discussing the social history of Soviet cybernetics. Here, Noorizadeh cites communication historian Benjamin Peters’s 2016 book, How Not to Network a Nation: The Uneasy History of the Soviet Internet, which describes efforts by Soviet scientists and bureaucrats between 1959 and 1989 to build a national computer network. One of the most compelling components of the cybernetic project was the All-State-System of Management (OGAS), championed by Viktor Glushkov and designed to digitally transform the planned economy. Computers were once considered “machines of communism,” a phrase that might sound foreign to North American ears trained to equate technological innovation with capitalism.

Bahar Noorizadeh, video still After Scarcity (2018). Mercer Union, 2019. Image courtesy the artist and Mercer Union, Toronto.

As Mahan Moalemi notes in the text accompanying the exhibition, Noorizadeh’s history of Soviet technology “treats history as technology,” in which recounting and remembering past futures might open up possibilities in the present. Noorizadeh is not alone in her interest in “past-futurism.” The “future” has become something of a buzzword in recent art exhibitions, looking at both contemporary art production and historical exhibitions highlighting movements such as Afrofuturism and Russian cosmism.

In taking up the history of Soviet cybernetics, Noorizadeh attempts to bypass linear theories of history based on the reckoning of binary oppositions—between failure and success, or socialism and capitalism. But does an emphasis on past futurity derail this linearity? It would seem that heterogeneity, the capacity for there to be multiple presents emerging out of multiple pasts, is vaunted here. However, the very structure of the film forces the viewer into a rapid linear, text-based historical lecture, which flying individual forms do little to break. The flashing, pulsing light, intense physical sound and fast-paced text keep the viewer’s body on high alert, rendering any escape of imaginative possibility signalled by the text to be physically impossible.

While this episode is historiographical in nature, Noorizadeh renders it in global economic experimentation as utopian, suggesting that “contingent histories are embryonic ideas.” What does come through in the essay on the future-that-never-was of Soviet cybernetics is that plans that don’t come to fruition do not necessarily represent failure. These corrections are the strengths of alternative historiography, but we might push further and ask what their rendering in film format does to augment the argument for alternative past futures. In hollowed-out architectural form, the emphasis on “reading” the film rather than affectively experiencing any evocation of alternative political imaginaries leaves a viewer wondering what aesthetic principles would enact such a future.

Paraphrasing Frederic Jameson and Slavoj Žižek, the late Mark Fisher described the concept of “capitalist realism” as the “widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it.” Fisher suggests that, while Francis Fukuyama’s infamous thesis on the “end of the history” has been widely refuted (and even recently recanted by Fukuyama himself), the overwhelming sense that there is nothing new has entered the cultural consciousness. In this atmosphere, the future would necessarily become the subject de rigueur of the avant-garde. But does this search for past forms fall into the trap of rendering the past and its attendant cold-war logic of antagonistic socialist/capitalist opposition as the only reservoir of political possibility?

Within Noorizadeh’s work this dilemma is presented as a formal question, one that gestures to some of the basic problems of modernism. Is aesthetic abstraction a nostalgia for a future that once was, one in which the disintegration of form led to possibility rather than chaos? Alternatively, does realism present the world as it really is, or does it freeze the present into an unpliable form? The negotiation between these extremes is given shape in the different strategies taken up in each of Noorizadeh’s films, leaving us wondering where she’ll go next.

“Bahar Noorizadeh: governance machines and the future of futures” was exhibited at Mercer Union, Toronto, from November 17, 2018, to January 19, 2019.

Emily Doucet is a writer and PhD candidate in the history of photography at the University of Toronto.