An Exhibition of Self-Portraits

In 1906 Picasso painted a portrait of Gertrude Stein. There’s an apocryphal story about the painting of this image. Gertrude Stein is said to have responded to the completed work by telling the artist it didn’t look like her. His answer: “It will.” And it did.

Gallery 454 opened its doors in September of this year. In a style characteristically confrontational, gallery owner Bill Lobchuk offered artists an invitation and a challenge: “Bring in a self-portrait.” Thirty-five people were contacted. Thirty responded with art. For some artists like Tony Tascona or Don Reichert, whose paintings are usually abstract, the challenge must have been tough—neither figure nor figurative images are regularly part of their repertoire. Other artists, whose work is usually representational, responded, interestingly, by presenting themselves almost as abstractions. Certainly, cryptic clues and symbols were present in a number of the pieces, in some cases to confound, in others to illuminate.

Curators have assembled exhibitions of self-portraits before but the pieces were done at different times, often centuries apart, and then brought together for the particular event. Here, at Gallery 454, was a show made up of commissioned self-examinations. Lobchuk said he wanted something special with which to inaugurate his new gallery and the idea of self-portraits interested him. “It’s a standard art-school exercise,” he told me, and he hadn’t done one since then.

The results were 30 views of ‘self’ looking out at the room, except they weren’t looking out, they were looking in. It’s the rare and fortunate being who can spend hours in self-scrutiny and be content with what she sees. Some of the portraits showed a reassuring consistency. That is, the artists saw themselves the way they’re seen by others. Some evidenced an unsettling candour and were courageously revelatory. Others were alarming in the distaste for their subject and still others showed an astuteness of character analysis that would have Sigmund Freud cheering. “I didn’t know she knew she was like that,” you said to yourself as you pried and snooped your way around the rooms. And while participation in this group show was voluntary, as a viewer I felt some of the discomfort of an inadvertent eavesdropper. Hours spent translating the face to paper is an extremely personal and solitary act.

Only in the rare case was it necessary to check the identifying label in order to name the portrait. But scrupulously representational or not, the portraits all were fictions, stories the artists told about themselves. Stories like these: these are the accoutrements, the trappings by which I can be identified; this is the image I present to mask my true being; if I were younger, older, taller, meaner, better or other, this is what I’d look like; this is how I think I’m seen; this is what I’d look like if ….

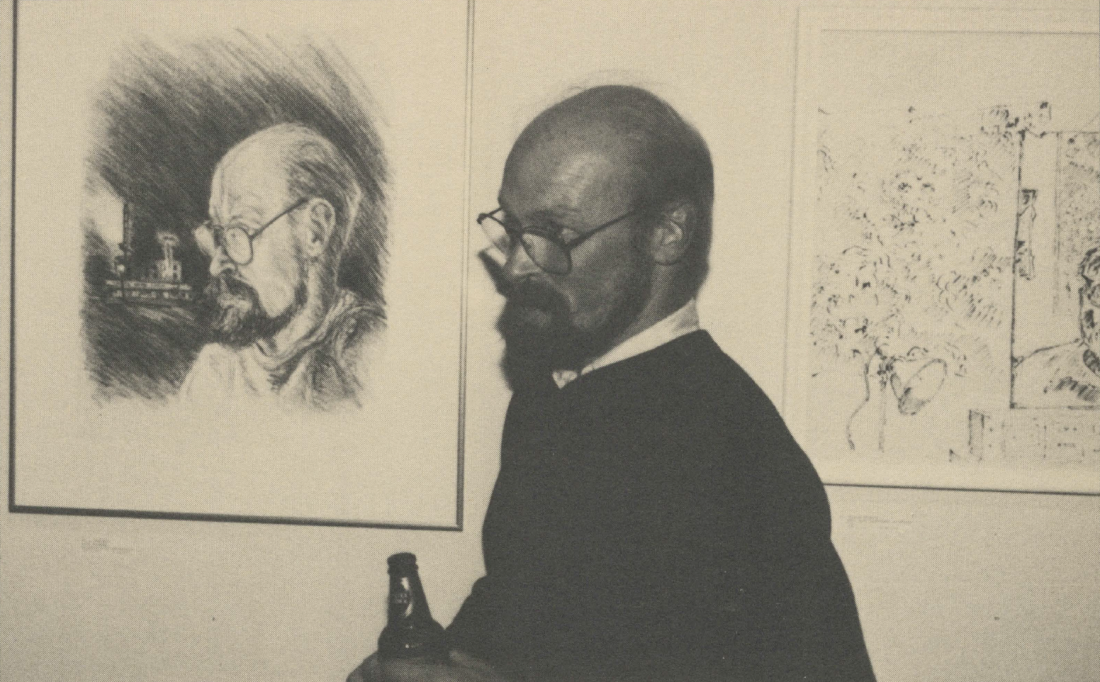

E.J. Howarth, 1987. Photograph by Alan Pakarnyk.

Bill Lobchuk’s self-portrait is a good example of this “what if” context. I know the man well and for me his oil pastel drawing was more a character study than an accurate visual rendering. I looked at his portrait with moustache trailing to either side of his chin. I said to him, “Your moustache doesn’t do that,” and he answered, “I know, but if I were a Cossack it would.” If I were—the self-portrait as romantic projection.

Louis Bako’s portrait is another romance—here the artist as buccaneer. In this elegant watercolour on paper the hooded, slightly tilted, eastern-European eyes are weary, have seen too much, lived too much. The effect is charming. He’s chosen a carefully controlled palette—muted reds, blues, purple and brown—to match his fatigued mood.

Diana Pura’s Still Life with Self Portrait is a coloured pencil drawing and one of the finest pieces she’s done. She presents herself arms laden with fruit, vegetables, a doll and the inimical plucked chicken. She’s dressed in a simple shift, a woman slender and shy as a young boy. The face is beautifully modelled, looking out almost reluctantly, barely meeting her own or the viewer’s eyes with a tentative, sideways gaze.

In looking at Michael Olito’s watercolour and oil pastel drawing, I can only think that Mike wishes he were a minotaur. Fierce, with blue-ringed eyes, blue shadows, blue moustache and a red, red mouth, the whole image successfully delivers an impression of the true size of the man.

Jordan Van Sewell, in clay, sits on a cushion, which rests on a cylinder, which is a lamp, which emerges from a sea, which is peopled by a variety of polychromed clay fish, one of which is the switch for the lamp. Van Sewell presides over this watery universe atop a pillow, like a Mediaeval Christ or Greek Imperial figure, and he’s elegantly and elaborately dressed, from his pointed shoes and finger rings to his harlequin-patterned suit. The orange hair and beard, the whimsy, and the skill and technique allow for no mistaken identity.

Les Brandt’s is an interesting piece. Self Portrait Stuck with Images, the title gives a clue to an adolescent obsession which remains lodged in his perception of self. The portrait is a large, solemn, frontal head done in acrylics, coloured pencil and ink. Tacked across the cheeks (stuck, as it were) with painted-on push pins are five female images—four nude and one Rubensesque-proportioned, swim-suited women—images with which he remains burdened and through which, it appears, he labours to see himself, or perhaps free himself.

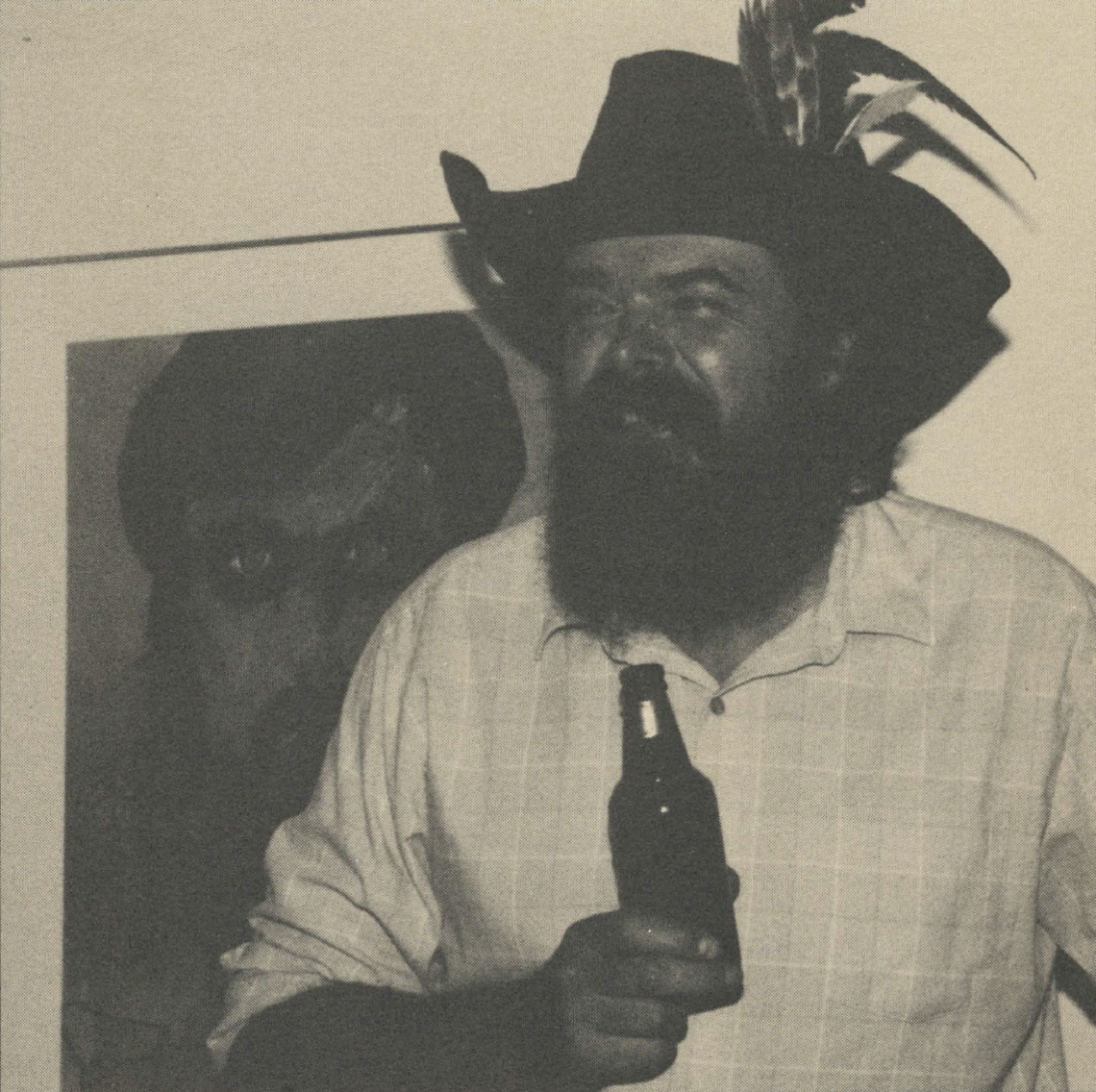

Michael Olito, 1987. Photograph by Doreen Millin.

By far the most ambitious piece in the show is Don Proch’s. He’s gone to enormous lengths to keep himself almost a secret. The net effect is an extremely beautiful, poignant little construction. This small, elaborate piece of art and technology, called Self Portrait: Revelation, Deception, is done with silverpoint, graphite and coloured pencil on fibreglass, with bone, electric and nickel pin construction. Hesitantly the piece unfolds, refraining from showing everything at once. If you want to see this artist, it’s going to take a little work. The piece consists of a flat box about 2½” deep, wall-mounted and supported by a metal rod housing the electrical wiring. The whole piece is covered in fine line drawings. The face of the box presents Proch’s eyes, worried and cautious. One iris is absent, a hole inviting the viewer. And there you stand eye-to-eye with the artist, looking inside his head. Do you dare? Inside is a night-time waterscape. A full silver moon, a pearly moon holds the early evening sky. It’s reflected on a barely rippling lake. Outside, on the box’s top, sits one-quarter of the crown or cap of the skull and it’s covered in finely drawn clouds. Between the eyes and arcing back to the wall are cross-sections of bone set into black fibreglass, the whole surface polished to a marble finish. The top of this arch bristles with thin chicken bones into which nickel pin wires have been inserted. Looking at the piece is like the tension of holding a wrist you’re sure would snap if you tightened your grip. In showing himself in this way, he’s done one of his most sensitive pieces in a long while.

Kelly Clark’s self-portrait in black pastels is called Janet’s Choice and you can see why. This man can draw and can draw himself. Here, the artist presents himself the way others see him. It’s a tender and close-cut image. The face is sad and intelligent, quiet now with just a slight expression of rebuke. I can’t remember a time when he wasn’t part of the art consciousness of this community, an art maker, an art watcher.

Rosemary Kowalski’s portrait, I Have Not Yet Forgotten, is a dour, tough and unrelenting portrait in which the artist looks more like Rodin’s Balzac than herself. There’s nothing to give a clue as to gender and the head floats disembodied on the surface, a brown paper cut-out with the edges melded flat to the paper by the impasto application of paint. A dark, sombre, plum red bleeds through the black overlay. It’s an interesting, haunting piece which leaves you asking why, while at the same time fearful of being given more than the piece already has.

There are other dark and troubling pieces in the show and there are pieces where clearly the artist felt it incumbent to be sociable and pleasant. Some are telling, some are telling nothing.

I’d commented earlier that I had a sense, while looking at the show, of being something of an eavesdropper. As a viewer you have to be outside this event. There’s an exclusivity here that can’t be brooked—a bit of a private club. It’s this. Self-portraits: no one but artists can do them. ♦

Meeka Walsh is the assistant editor of Border Crossings magazine and a freelance art critic.