A Dependant Inquiry into Certain Normal Predicaments of Human Divinity

Reading Let us Now Praise Famous Men together, again

“If I could do it, I’d do no writing at all here. It would be photographs; the rest would be fragments of cloth, bits of cotton, lumps of earth, records of speech, pieces of wood and iron, phials of odors, plates of food and of excrement…. A piece of the body torn out by the roots might be more to the point.”

This line of James Agee’s and Walker Evans’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, 1941, is cited by curators Freya Field-Donovan and Alexandra Symons Sutcliffe on the opening wall of their recent exhibition “Famous Men” at Gallery 44 in Toronto. The pair (London and London/ Berlin-based, respectively) have been reading Agee’s and Evans’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men for a while now. Tending to Agee’s instructions in the book’s preface that “the text was written with reading aloud in mind,” Field-Donovan and Symons Sutcliffe have held sessions in which they lead group readings of sections of Agee’s and Evans’s text. The exhibition—which developed out of this sustained collective reading practice—draws on intertextual connections between Agee’s and Evans’s book and a range of artworks and texts. The show featured work by Helen Levitt, Kadish Morris, RaMell Ross, and Lorenza Mondada with Nicolle Bussien and Sara Keel, in collaboration with Hanna Svensson and Nynke van Schepen.

Describing their project, James Agee wrote, “The effort is to recognize the stature of a portion of unimagined existence, and to contrive techniques proper to its recording, communication, analysis, and defense. More essentially, this is an independent inquiry into certain normal predicaments of human divinity.” The call to “recognize the stature of a portion of unimagined existence” underlines both the anthropological and humanitarian interest of Agee and Evans in their subjects and their role in the production of New Deal-era government propaganda.

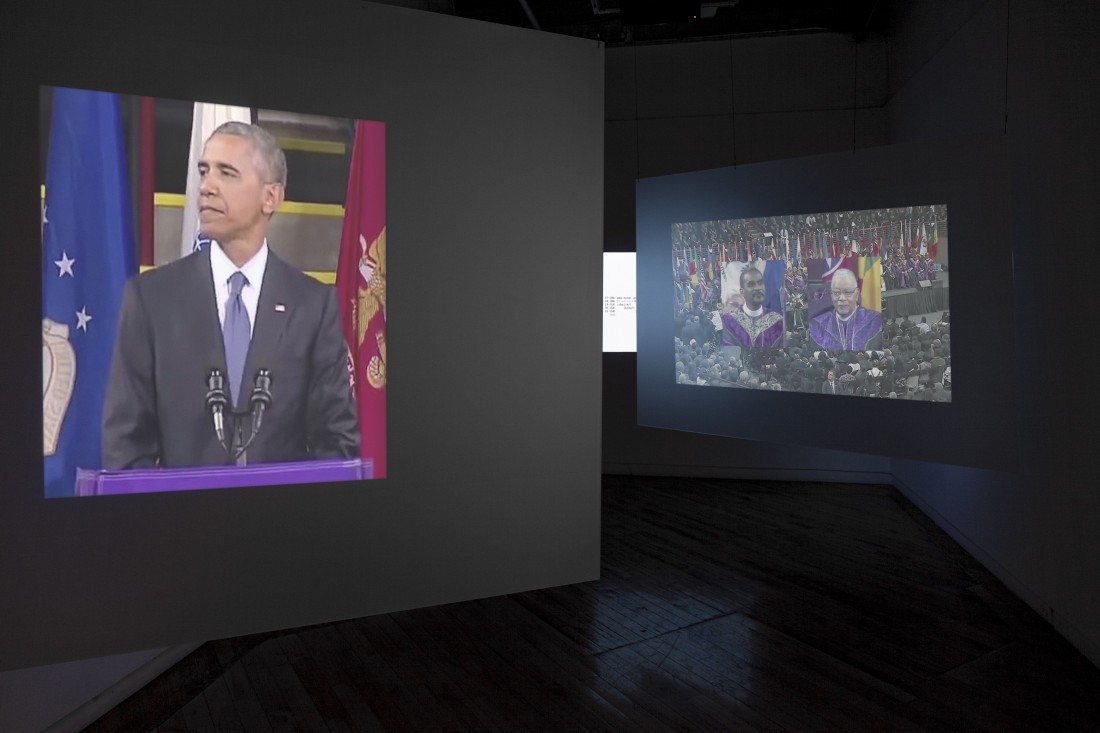

Installation view of “Famous Men” at Gallery 44, Toronto. Photo: Darren Rego. Images courtesy Gallery 44.

More to the point, Agee suggests, would be something beyond image or text, more akin to installation or performance. Denying a single orator or expert, the act of collective reading is, for Symons Sutcliffe and Field-Donovan, “a social pedagogical practice.” Group oratory is an act that questions the relationship between representation and performance, not unlike that modelled in the experiment of Agee’s and Evans’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Like an exhibition, a reading group is a risk. Who hasn’t been (or intended to be) in one that fizzled, failed or was taken over by brazen personalities staging space for their own expertise? Nonetheless, I participated in the Toronto iteration of Field- Donovan’s and Symons Sutcliffe’s reading group. A small group of us gathered around the table of reading materials within the exhibition space and read, one after the other, from photocopied pages of the text. Forgoing group introductions and thereby avoiding individual posturing, the group read from the preface to Agee’s and Evans’s text. In vocalizing the text amongst Helen Levitt’s and RaMell Ross’s photographs, the collective rhythm and syncopated anticipation of individual performance had a levelling effect. The experience of publicly reading Let Us Now Praise Famous Men exceeded text and image as we savoured and stumbled over Agee’s lengthy sentences, chuckling at artistic hubris disguised as modesty and pausing to discuss resonances with the present.

In an attempt to communicate the social problems of the Great Depression, in particular those of the rural South to those in the urban North, the writer Agee and the photographer Evans undertook the collaborative project of documenting the unvarnished existence of the average white sharecropper family in Hale County, Alabama (then, as now, a predominantly Black community). The project began in 1936, when the pair, both staffers at Fortune magazine, took up residence in the community in order to best observe the families. The resulting document was eventually rejected by the magazine but published as a book in 1941. Within the book Agee’s expansive text cohabits with a selection of Evans’s photographs featuring many now iconic images such as portraits of members of the families and images of their homes. While generating sympathy from the viewer, the photographs often appear to remove the individuals from the rhythms of everyday life and frame the entirety of lives within the language of dust-bowl destitution.

Installation view, Lorenza Mondada, Nicolle Bussien, Sara Keel, Hanna Svensson and Nynke van Schepen, Obama’s Grace, 2016, 3-channel video installation, HD colour, sound. Co-produced by ZMK Karlsruhe and University of Basel.

Shortly before Agee’s declaration that the text was best read aloud, a paragraph outlines the proposed relationship between photograph and text. Declaring at the outset that the “photographs are not illustrative,” Agee suggests instead that text and image are “fully collaborative.” He recognizes that any possibility for seeing the text in the image and the image in the text will be wholly undermined by the “impotence of the reader’s eye” but sought to resurrect an understanding of text-image relations that refused to rely on any hierarchy. Expressing some regret that the project was in the end only a book, Agee closes his preface by writing, “This is a book only by necessity. More seriously, it is an effort in human actuality, in which the reader is no less centrally involved than the authors and those of whom they tell.” Arguing for an understanding of reading as primarily relational, Agee suggests that interpreting text and image is a collective endeavour.

As well as serving as a revelation between reader and text, reading collectively and aloud has a long history in both revolutionary organizing and religious study. The practice has in recent years become a favoured structure for reading groups housed in, or adjacent to, contemporary art spaces. Projects such as the Feminist Duration Reading Group (London) and EMILIA-AMALIA (Toronto) often draw explicitly on traditions and text from radical histories, including 1970s Marxist-feminist groups such as the Milan Women’s Bookstore Collective. In these instances, the practice of collectively reading aloud theoretical and historical texts is aimed at creating a shared and durational experience of the text and decentering external expertise.

RaMell Ross, Here, 2012, from the series “South County, AL (a Hale County).” Archival pigment print.

The act of decentering reading (so often understood as a solitary act) shares certain ideological characteristics with the history of documentary photography. Elizabeth McHenry, author and associate professor at New York University, for example, has documented the history of African-American literary societies in the Antebellum South. While McHenry cautions against tracking a linear trajectory from 19th-century reading groups to contemporary organizations,nshe suggests that many such groups are informed by similar political concerns.

Picking up on Agee’s and Evans’s “effort in human actuality,” though not uncritically, Field- Donovan and Symons Sutcliffe bring a different series of objects and texts into conversation with Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Levelling hierarchies between image and text, a reading table displayed books germane to the practice of documentary photography in the early 20th century and the particular interests of the contemporary artists and curators involved in staging the exhibition. As a reader, this is always my favourite part of every exhibition, and in this case particularly so. Not only was this a media-historical gesture on the part of the curators (every image in the room circulates in more ways than one), but the table visualizes a splintering of the primacy of Agee’s and Evans’s text in history, the space of this exhibition and in the history of photography more broadly. One of the unique achievements of this reading practice (and I’m including both reading group and exhibition here) is that it focuses our attention on a closer reading of the individual text and refracts our frame of reference outwards and beyond the weighty tome itself. This process of refraction, breaking down and through the light, is evident across the exhibition. The works themselves exceed the frame, drawing from larger bodies of work, different media, pools of collective image making and sharing, and the broad expanses of public life.

Lorenza Mondada’s video installation Obama’s Grace offers a different yet corollary approach to this problem of representation and the politics of documentary. It is constructed of YouTube imagery of President Obama’s eulogy for Reverend Clementa Pinckney, who was murdered along with eight of his congregation members in the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston in 2015. In the midst of his speech, Obama broke into a rendition of “Amazing Grace” and was quickly joined by the entire congregation, a collective oratory exercise unto itself. The two-channel video is accompanied by a third, offering graphic documentation of Obama’s movements, akin to a dance score (as the curators note). This partitioned representation of one of Obama’s many iconic speech acts registers both the redemptive possibility offered to many American voters by Obama’s presidency and the limits of the system of political representation within which any American president operates.

RaMell Ross, Brothers Z, 2012, from the series “South County, AL (a Hale County).” Archival pigment print.

Political performance is not the only domain of representation under question here. Photographer and filmmaker RaMell Ross moved to Hale County, Alabama, in 2009 to teach photography and coach basketball. In the title cards of his documentary film Hale County, This Morning, This Evening, he writes that “this is when the discovering began … I began filming, using time to figure out how we’ve come to be seen.” Ross’s lyrical documentary is composed almost entirely of slow lingering shots around Hale County, intercut by a few brief clips from the unfinished 1913 silent film Lime Kiln Club Field Day, considered to be the oldest surviving film with an all-Black cast, featuring the Bahamian-American actor Bert Williams in blackface in the leading role. Ross’s inclusion of the film is interspersed with shots of a large white plantation home, speaking both to the charged history of the representation of African Americans in American cinema and to the question with which the film began: how to use “time to figure out how we’ve come to be seen.” Every image in the film feels as though it is made of animated still photographs, capturing the intense beauty and banal joys of everyday life and drawing out this slow and long look at the extraordinary ordinary. Ross’s feature-length documentary was not in the exhibition; present instead were a series of still images of parallel moments from life in Hale County. In one of Ross’s images a pair of jeans and sneaker-clad legs emerges from the bed of a silver Ford truck; another pair of legs bare to the knee with feet clothed in white ankle socks peeks out from under the body of the truck. In another of the photographs included in the exhibition, a park’s sagging fence is weighted by the body of a small child dressed in red, staring up at the grey sky.

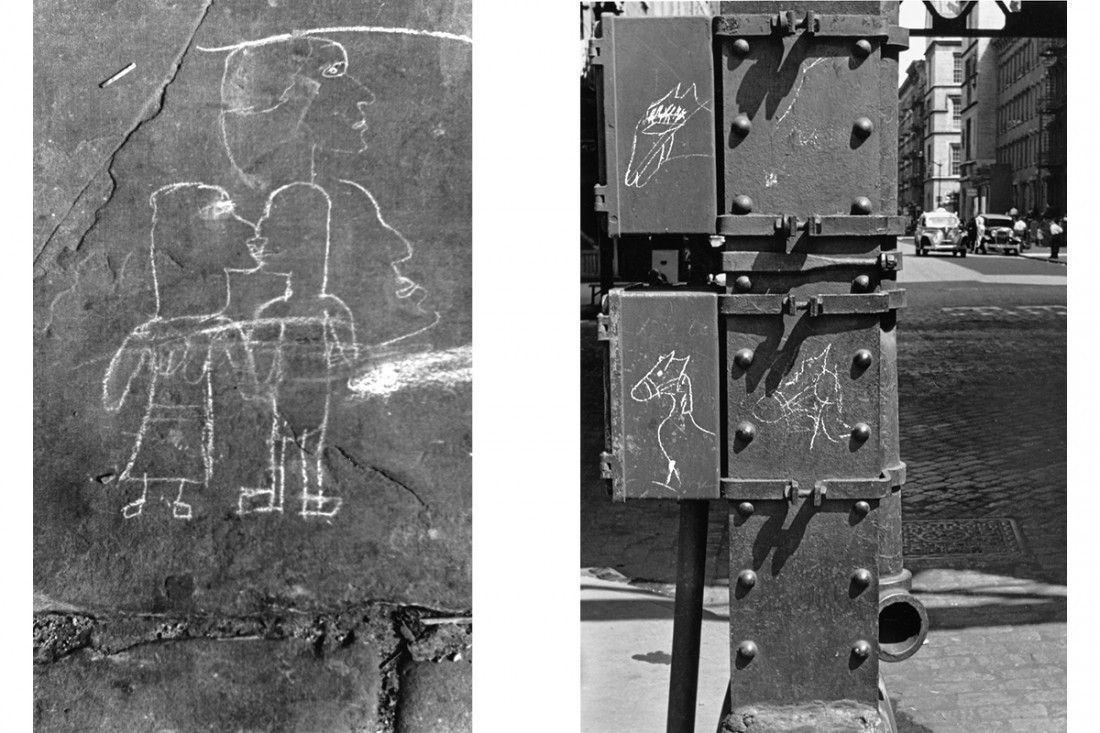

Helen Levitt, New York, c. 1940. © Film Documents LLC. Courtesy Thomas Zander Gallery.

Taken in the same county as the photographs featured in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Ross’s still images speak across decades to Helen Levitt’s equally still images of children’s graffiti in New York City in the 1940s. While neither offers a simple corrective, both sets of images are in dialogue with the vision of American life narrated by Evans and Agee in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Levitt’s images of children, documented here in the traces of the joyful adornment of their surroundings, are shown to be actively reimagining their place in the world. Outside the space of this exhibition, Levitt and Agee were also collaborators. As one of the opening title cards of their 1952 collaborative film In the Street proclaims, “The streets of the poor quarters of great cities are, above all, a theater and a battleground.” Urban scenes therefore offer, for Levitt and Agee, an opportunity to capture “an image of human existence.” In contrast to many of Evans’s images included in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Levitt’s images open up a sense of possibility inherent in urban life. A view of concrete steps from above zeroes in on a misspelled and playful phrase, “A decetive [sic] lives here.” The child detective who wrote these words lies beyond the frame of the image. In another of Levitt’s photographs, a dozen white eggs in a box in an advertisement have sprouted individual cheery faces. Like Ross’s images, Levitt’s photographs document playful presence, yet resist portraiture in its more conventional forms. Characterized by both sorrow and joy, play and loss, Levitt’s images offer up the city as a stage for human imagining. Even when the human body is absent from the image, a line, a drawing suggests the hidden child revelling in her figuration of the world.

Amidst these images, a stack of printed sheets of paper on the floor offers some words to anchor them in time. Kadish Morris’s text, A Gospel, speaks again to Ross’s interrogation of the history of representation. Morris writes, “Your removed / picture leaves / behind it / whatever is / the opposite / of a stain.” Morris’s brief text follows visitors out the door but also gets at a central question (one of many raised here) of documentary practice: Is the image the only form by which to record human existence?

My thanks to Jessica Evans, Hannah Doucet and Rhiannon Vogl for their comments on this text.

Emily Doucet is a writer and PhD candidate in the history of photography at the University of Toronto.