Plane Talk

An Interview with Eli Bornstein

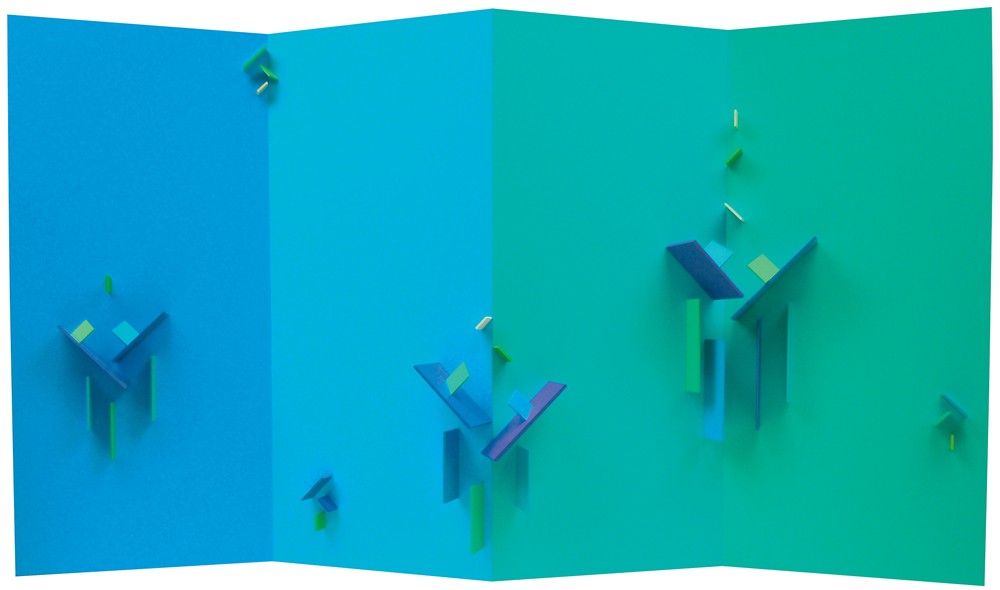

Quadriplane Structurist Relief No. 14, 2008–2009, acrylic enamel on aluminium, 86.3 x 148.2 x 22.1 inches. Collection of the artist. Courtesy Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon.

INTRODUCTION

Eli Bornstein has figured out time. Everything about the 92–year-old Saskatoon-based artist admonishes time’s tyranny over human life. He has lived in the same city for 63 years, taught in the Department of Art & Art History at the University of Saskatchewan from 1950 until his retirement in 1990, edited The Structurist, a magazine singularly devoted to investigating the origins and the practice of structurist relief for 50 years, making it the longest running art journal in the country; and not uncommonly, worked on one of his reliefs for periods of three to five years.

His life is inextricably intertwined with nature, the force that has been his muse and adversary over the course of his lengthy and distinguished career. “When you look at nature you realize how primitive whatever you’re doing is,” he says in the following interview, “whereas in nature it seems so effortlessly achieved.” Bornstein admits that finding the time to make art was a “juggling act,” but there is no evidence of that struggle in the form and surface of his meticulously constructed reliefs.

Over the years their palette evolved and the structure has evolved from simple monoplanes to two, three and four-part multi-plane configurations, but what has remained consistent is Bornstein’s passion for rendering nature’s inexhaustibly mutable light. In this regard, it is telling that the title of his exhibition of recent work is “An Art at the Mercy of Light.” (The exhibition, curated by art historian Oliver Botar, opened at the Mendel Gallery in Saskatoon and toured to the School of Art Gallery at the University of Manitoba from November 12, 2013 to February 21, 2014.) Mercy is an attribute that is both given and asked for and that doubleness is an accurate depiction of Bornstein’s relationship to nature.

Quadriplane Structurist Relief No. 14 (detail), 2008–2009.

The structurist relief is a hybrid of painting and sculpture and its pedigree has been thoroughly documented, particularly in various special issues of The Structurist, where Bornstein considered the connections between art and a diverse range of issues, including ecology, ethics, the environment and the ways in which the visual and the verbal intersect. He acknowledges that structurist relief synthesizes colour and form; the former is traceable through Monet and Impressionism and the latter through Cezanne, Malevich and Cubism. Somewhere in the middle is Mondrian, an artist whose influence is evident in works from 1958, like Structurist Relief No. 17. The relatively restrained palette of this early work has blossomed to the oranges and greens of Double Plane Structurist Relief No. 2–1 (1966–71); to the blues, lavenders and greys of Double Plane Structurist Relief No. 20, (Arctic Series), (1969–72); through to the intense close-valued range of lemon and lime in Quadriplane Structurist Relief No. 6 (1999–2000). While Bornstein has avoided naming his works except through numbers, the parenthetical additions—“Arctic Series,” “Sea Series,” “Summer Growth Series,” “Sunset Series”— indicate that from the beginning he has been operating inside a landscape tradition, not only firmly rooted in the history of art, but no less secure in the history of art-making in Saskatchewan, a province that has produced an enviable number of fine landscape painters.

Eli Bornstein has elsewhere referred to “nature’s luxurious abundance and abandon.” It is a lovely phrase and articulates a notion to which he has absolutely given over. I think of the way he looks at nature as a kind of love affair, full of wildings and tamings, wildings from looking and tamings of making. The parallel that comes to mind is the famous description of Cleopatra by the courtier, Enobarbus, in Shakespeare’s play that carries her name. When Enobarbus says, of the exotic queen that she “beggar’d all description,” I am reminded of Bornstein’s acceptance that our attempts to equal nature become a measure of our inadequacies. His work is “not a depiction or a direct representation. It’s more a sense of being in nature than a desire to represent it.” Eli Bornstein’s sense of joining rather than competing with nature, then, is both homage and humbling. As Enobarbus says, neither age nor custom “can stale her infinite variety.”

The following interview was conducted by phone to Saskatoon on Saturday, September 21, 2013.

INTERVIEW

Border Crossings: I know you used to walk along the riverbank close to where you live. Were those walks inspirational? Was being in nature something you could draw on?

Eli Bornstein: Absolutely. I think my survival in Saskatoon for all these years was partly because of where I lived. There are places where I would walk that would make you think you were 50 miles from Saskatoon; they were still quite wild and not many people got there.

Are the reliefs a depiction of the nature around where you live, or is a larger Nature being reflected in the work you were doing? I think more the latter, although they are not exclusive of one another. The experience of nature gets transformed in the process, so it’s not a depiction or a direct representation. It’s more a sense of being in nature than a desire to represent it. It’s metaphorical.

Because the structurist relief exists in three dimensions, it is not only about space but is in space as well.

Exactly. That’s why I see it as a new medium. It’s curious because when I was in high school and university my interests were in both painting and sculpture. I couldn’t think of one as more important than the other and I couldn’t let one go in favour of the other. Once I started looking at things, I seemed to be attracted to colour and light as well as to form and structure. I came to see making the physical relief as a synthesis of the two things. I didn’t have to give up either interest but was able to bring them together and find a whole world of things and qualities neither painting nor sculpture entirely possessed.

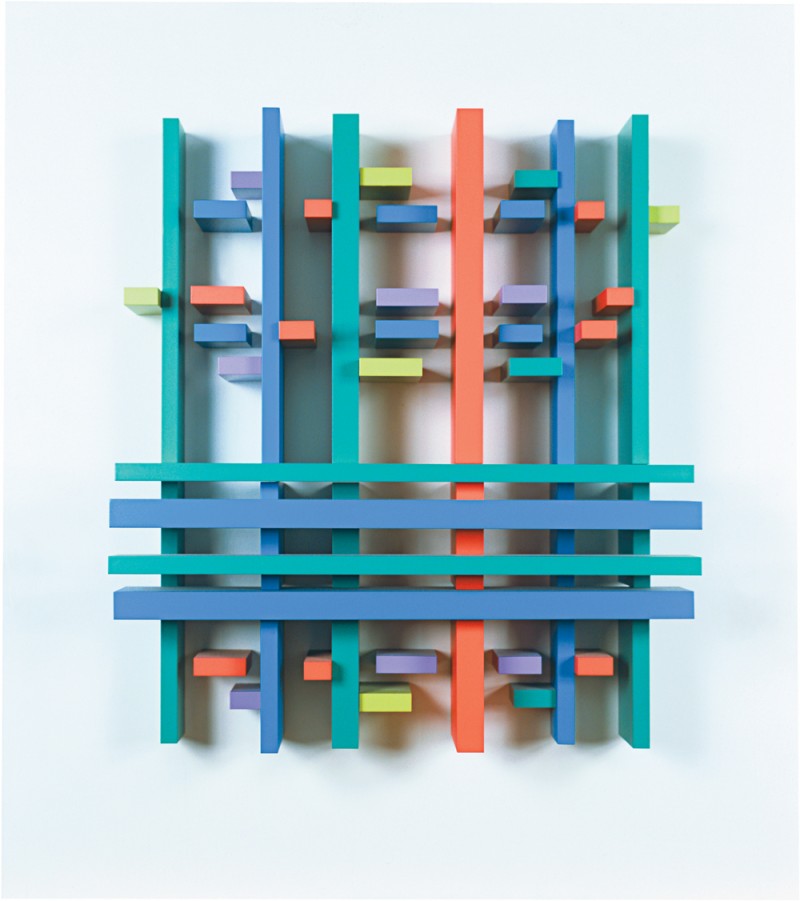

Quadriplane Structurist Relief No. 4, Sunset Series, 1997–99, acrylic enamel on aluminium, 95.2 x 155 x 19.3 inches. Collection of the artist. Courtesy Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon.

When you are making the reliefs, can there be too much colour, and then the relief tips the balance in favour of painting? And if there is too much form it tips in favour of sculpture? How do you avoid crossing either of those lines?

It is without question a balance and an integration. Colour can take over and suppress or ignore structure and space, and the reverse can also happen. I sometimes say it’s like driving a team of four horses that you are trying to keep moving together and not let one take over. ** Do you figure out what are the component parts and where they should go in preliminary drawings before you make the reliefs?**

One of the problems of the medium is that it is difficult to make drawings that deal with actual space and projection. I often make pencil sketches and watercolour sketches, but they are never adequate and I’m sure they mean more to me than to anyone else. The same goes for structure and for space. You can do them easily enough but the elements of colour and light immediately become problematic. I’ve also worked with models where I use light and colour, structure and form at the same time. And I’ve worked directly, where the model itself evolves into the final work. Each has its own problems. So there is no simple way of working. Another consuming subject I have often thought about is where intuition or instinct comes from and how it is engaged in the work. There is something inexplicable and quite mysterious about the process.

It would be useful if you could take me through the making of a structurist relief from idea to execution.

It doesn’t always proceed in the same way. A work starts with a sense of something I want to achieve that I haven’t achieved before. Very often my intentions change and are affected by the nature and the limitations of the medium itself. I may start with some very rough sketches with pencil, or maybe coloured pencils and papers. If it’s a multi-plane relief or a construction I usually begin with the structure of the work. So that is a basic start already. Then I proceed just temporarily cementing pieces together. Sometimes the colour is stronger than the structure, and sometimes the reverse is the case. Of course, the intent changes as the work progresses and I’m not always able to achieve what I wanted. Or I achieve some of those things at another time.

Do you actually have colour pieces like a painter would have on a palette?

I do. Over the years I have accumulated a substantial number of pieces in different sizes and colours, but you never have enough. I have found ways to make things temporary but strong enough to last for a few weeks or months. Once I feel I can get what I want I proceed to make an exact drawing of the entire work, so I have all the sizes and dimensions. The drawing then becomes the permanent record of how this work will be put together.

Do you number the pieces?

Yes. And the drawings are quite absolute in their detail, so I’m not guessing at how it all works together. The colours have been determined; nothing is left to chance or guesswork. The two-dimensional drawing is like architecture.

Is the process of putting it together a painstaking and time-consuming one?

It is certainly labour intensive. The fact that they look so clean and precise is not an objective. It’s seeing the thing the way I want you to see it and not introducing any distractions I don’t want. It’s a learning process. I think seeing art is an art in itself and that you have to see it in ways complementary to the way the artist created it.

Structurist Relief No. 3, “Sea Series,” 1966–67, enamel on Plexiglass and aluminium, 86.5 x 61 x 15.6 cm. Photographs: courtesy the artist.

Was moving to double and multi-plane reliefs a significant shift in your thinking about spatial relationships?

It comes back to the relief medium and the relationship of the work to the wall. In the beginning, there was a strong connection to painting and the two-dimensional ground plane, or what I called in an essay, “the window on the wall.” That window and the wall itself presented some strong limitations. The double-plane relief occurred in the mid ’60s when I was trying to find ways of introducing more space and more light into the work. It felt quite liberating in the sense that I was able to include more of the inherent qualities of the medium. Of course, the other big move was toward the free-standing constructions, which began to work completely in three dimensions.

So they came off the wall and into space in a more complicated way?

That’s right. They are on a pedestal and the viewer moves around them. I was influenced by a book called The Birth and Rebirth of Pictorial Space by John White. I read it before I read Charles Biederman’s book in 1954. It was very interesting to learn about pictorial space, with which White dealt a great deal, particularly in its origins and during the Renaissance.

But you never accepted a hierarchy that said sculpture was more or less important than painting. They always seemed co-equal.

It’s true. I couldn’t take one position or the other, but the arguments were fascinating and in a way that has continued. Art has changed and has had to find its own identity, but it is still involved in the discussions about two and three dimensions. I’m right in the middle and feel there are a lot of possibilities that haven’t begun to be explored.

How much painting of individual pieces is involved?

Once the model and the drawing have been finished, then I’ve got all the information I need. It’s like a piece of music that has been written out. All the notes are there. The performance means cutting all the material, painting and then putting it together for the final assembly. The pieces are screwed on. It’s simply that for the work to be moveable and transportable, it has to be assembled in a permanent way. So over the years I have developed new ways of putting things together that are permanent and yet detachable. I haven’t gotten around to patenting them yet.

Was the organic quality that one finds in nature an informing principle in your shift to a more complicated kind of structure?

Absolutely. When you look at nature you realize how primitive whatever you’re doing is, whereas in nature it seems so effortlessly achieved. The organic aspect in my work results from that connection I feel with Nature.

Structurist Relief No. 3-II, “Canoe Lake Series,” 1964, enamel on Plexiglass and aluminium, 27 x 24 x 5.5 inches.

Another kind of organic growth emerges out of looking at the first issue of The Structurist. In the magazine, you and Biederman argue that structurist relief started with Cezanne and it continued with Cubism from Monet through Mondrian. Was it necessary to develop a theory that both rationalized and described the process of coming to the evolution of structurist relief?

It was. I think that history is extremely important. Long before I knew about Biederman, I had a strong interest in Impressionism and Cezanne. For a while I went to the Art Institute of Chicago, where everybody was particularly taken by Expressionism, and I was painting like Cezanne. My teacher said, why are you painting like that? It was simple: upstairs in the gallery I had these wonderful Cezannes to look at.

So Cezanne gives you the structure and Monet and Impressionism give you the colour? Those are the two components that end up being central to structurist relief?

Yes. But a lot of other artists who felt that way didn’t necessarily end up doing reliefs. I wasn’t thinking in any rigid or deterministic fashion, and one thing didn’t automatically lead to the other. Often it led to something else. One thing I strongly disagreed with Biederman about was his contention that Cezanne had a specific formula for creating his paintings. That was not my experience of seeing Cezanne. Biederman ended up writing a book called The New Cezanne and making his deterministic theory of Cezanne’s methods and development. There were other differences between us. My interest in science and biology and my connection with Darwin was quite different from his interest in science and physics. There seems to be a different paradigm in the way physicists and biologists approach things. But what first attracted me to Biederman was that he brought so many other interests, such as general semantics, into art. Art was related to many other things and these things had to be looked at and thought about.

The British poet and aesthetician Samuel Taylor Coleridge has the notion that “the whole is prior to its parts.” He also calls Nature “the prime genial artist.” Do you subscribe to the idea that the whole precedes its parts, and if that is the case, then is making art simply discovering something that already exists?

Off the cuff, I don’t think I would subscribe to the idea that it’s all out there pre-existing. The possibilities are almost infinite. Coleridge’s idea assumes there is an ideal that exists someplace just waiting for people to discover it.

Hexaplane Structurist Relief, 2003, acrylic enamel on aluminium, 170 x 342 x 21.5 inches. Synchrotron–Canadian Light Source building, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon.

You have written that “it’s not in man’s power to design totally and with finality.” I know you see nature as being inexhaustible, and I wonder if there is a frustration in the fact that art can never finally answer all the questions that you pose because we’re incapable of designing with totality and finality.

I have certainly felt frustration in my art making but I would tend to agree with those human limitations and our capacity for perceiving things. I think certain things will always remain inexplicable. One is the phenomenon of death. We have always had great difficulty in dealing with it, which brings us to the religious impulse and why it is there, and will continue to be.

As you have become older does the religious dimension enter into your thinking?

Even as a child I thought about death, which opens up a whole other question about art and religion. The notion is often put forward that with the failing of so much organized religion, people see art as a new religion.

And nature as its cathedral?

That’s lovely.

You seem to be a latter-day pantheist. You say that looking at a tree is almost a religious act.

I guess there is something about that. We are all of us mixtures of so many things.

There was an early version of The Structurist wasn’t there?

Yes, a proposed magazine with Joost Baljeu. He was Dutch and I met him on my sabbatical in Amsterdam where I was living for nine months. He was very interested in Mondrian and Van Doesburg and very knowledgeable about both of them. He had done some publishing before, and we had a lot of discussions about what was wrong with art and art magazines, and why there was such terrible art writing. Out of this came the notion of starting an art publication. We decided to call it Structure and the two of us were involved in doing the first issue. There was an opening at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon and he and his wife came over and joined the department for one year. As things often happen, different viewpoints and misunderstandings emerged and we came to a parting of the ways. He went back to Holland and published a magazine called Structure.

But the idea of a magazine stayed with you and you started The Structurist, which survived for 50 years.

From the time I was 18 years old I kept a journal. I found out how important writing was in figuring out what I fully thought about things. The discovery through writing absolutely amazed me. I carried a notebook around but then I stopped. When we started Structure the idea was that Joost and I would have an article in the first issue, so I spent a good part of my sabbatical writing what was going to be my contribution. I found the reading and research quite fascinating and because of it I started keeping a journal again in 1980. The first issue of The Structurist came out in 1960 and then it had its own momentum. I never knew from issue to issue that it was going to continue. I was juggling teaching and making art with running the magazine, where I did all the work, including being editor, proofreader and janitor. It was published annually until 1972, and then I decided to make it into a biannual.

Tripart Hexaplane Construction No. 2, 2002–2006, acrylic enamel on aluminium on anodized aluminium and concrete base, 205.25 x 107.8 x 107.8 cm. Collection of the University of Manitoba. Photograph: courtesy the artist.

Is what you do primarily phenomenological? I mean, it’s based on looking more than theory.

My only hesitation in saying yes is that there are schools of phenomenology and I’m not sure they apply to me. But in the last issue of The Structurist I had read a new translation of Goethe and I found him a phenomenologist in that he kept stressing the importance of looking and seeing. In his case, he was looking at plants and how they grow.

In that sense Goethe is closer to biology than to physics.

Exactly.

Is there something that makes the North American variation of structurist relief different from what came from the continent or from England?

When I first went to Europe and met a lot of the English artists who were making reliefs, Mary Martin, Anthony Hill and Victor Pasmore, and then in France Jean Gorin and George Vantongerloo—I did feel the difference was in their connection to nature. I was very influenced by Thoreau, who was himself influenced by Emerson, and I don’t know if there were any such equivalents in Europe.

How would you characterize what shows up in the quadraplanes and the hexaplanes as different from what you did before? Where has this most recent work taken you?

It’s a good question. There are definitely big changes, and that is why I am so anxious to get back to work in the studio. I feel I’m able to get more of what I want in terms of space, structure, colour and light—that is very general, I know—but I just feel more freedom about using them. I also feel some of the connection with nature is more illuminating, not in any direct way but in terms of response.

You name the new work parenthetically, so there is the “Sunset” and the “River Screen” series, which draw attention to that connection to nature. Certainly, Quadraplane number 4, in the “Sunset” series, with the slightly lavender-inflected red, can be read as being about the prairie sky.

I’m aware that giving titles to abstract work presents a problem. It directs the viewer to look for representational cues. It is very interesting how many viewers who see abstract work without titles often make their own associations with Nature. You use a title and people immediately and mistakenly look for literal clues in the work. I much prefer self-discovery. Unfortunately, numerical description makes identification and communication regarding individual works difficult or impossible. “Series” can be useful although it continues the problems of literal description. Classical music has largely managed to resist using literal descriptions for centuries.

I am delighted to hear you say that you can’t wait to get back into the studio because there are things you have learned from this most recent work with which you want to continue. Is that what keeps you going?

It is. And it makes me both happy and regretful because I can’t not do that. But at the same time, art is a very demanding mistress, and you are constantly performing a juggling act to find enough time to do your work.

Back in the ’40s you made furniture, and while you didn’t know who Frank Lloyd Wright or Gerrit Rietveld were, you were making furniture that looked like theirs. Did you continue to make furniture or was it a young man’s passing habit?

I stopped doing it, although when we built our house I did make some furniture, since it was the quickest way to get something that we liked. But I was amazed when I did see Wright and Rietveld.

I have a sense that for you art and life have always been very close, that you have made your life artful. Has the pursuit of beauty been something that has manifested itself in the different layers of your life?

Absolutely. I don’t recognize that artificial hierarchy that assumes one art is supreme and another is quite meaningless. I think it was Mies van der Rohe who said that designing a chair was as much of a problem as doing a building. And as much pleasure can come from doing one as the other.