Marcel Barbeau: The Colour of Change

Marcel Barbeau was born in Montreal in 1925 and has been making art continuously for 65 years. A student of Paul-Émile Borduas at the École du meuble in 1944, he was a signatory of the famous Refus global, the manifesto credited with setting the stage for Quebec’s transformation from a closed, provincial to a modern culture. Released on August 9, 1948, at the Librairie Tranquille (could a venue ever be more ironically named?), the Refus global remains an extraordinary document even today. It translates as “Total Refusal” and that is most assuredly its tone and intention. Characterizing Quebecers as “a little people, huddled to the skirts of a priesthood,” and “trapped by an emotional attachment to the past, by self-indulgence and sentimental pride,” it calls for a definitive break with all societal conventions. The text emphasizes dynamism, change and the necessity of unpredictability. “The passionate act breaks free,” the manifesto declares, by rejecting “static reason and paralyzing intention.” This aesthetic call-to-arms was immediately attacked by the press and the Catholic Church, both of which were supportive of the Duplessis government. Borduas found himself fired from his long-held professorship and his marriage in ruins.

The effect on Barbeau, who was at the time jobless and unmarried, was not as evidently dramatic. He had enrolled at the École du meuble to learn how to make furniture and, at his own admission, knew nothing about, and had little interest in, art. But he noticed, while passing in the hallway, that the art class run by Borduas was particularly rambunctious—“people were hollering and talking independently”—and he received permission from the Director of the School to transfer into the class.

Rétina 400, 1956, acrylic on canvas, 46 x 46”. Photograph: Flip Image. Courtesy the artist.

The move changed everything. Borduas recognized something in his young acolyte that Barbeau hadn’t recognized in himself. Their relationship would remain intense until Borduas left for New York and, ultimately, Paris. At one point, Borduas was so disapproving about a body of work that Barbeau actually destroyed the paintings. On the evidence of surviving photographs of the work, it was a hasty decision, but it does indicate the unusual power Borduas had as a teacher and mentor. Barbeau recollects that, a month later, Borduas admitted he was probably hasty in his wholesale dismissal of the work. As Barbeau diplomatically puts it, he could be “moody.” What seemed to have most thoroughly influenced Barbeau as a result of his involvement with Borduas and the Automatistes was a sense of the necessity and desirability of change. Whether by inclination or persuasion (my guess is some combination of both), Barbeau has been migratory, moving from one kind of painting to another, as well as moving between art forms. In his lengthy career, he has made paintings, sculptures, drawings, and done collaborative painting performances with musicians and dancers.

He had participated in the Automatistes exhibitions from the beginning and his earliest paintings indicate a captivating fluidity. Veillomonde, an oil on canvas painted in 1946 and now in the collection of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, is a remarkable achievement for such a young and inexperienced painter. It was exhibited in the second Automatistes exhibition held in the apartment Pierre and Claude Gauvreau shared with their mother (these domestic exhibitions were the pattern developed by the group), and it was Barbeau’s first sale and one of his earliest paintings. Veillomonde is composed of three abstract bouquets of mark clusters that shimmer on the surface of the painting. The palette of rusts, reds and tan, with additional strokes of broken white and grayish green, is evidence of a subtle and accomplished tonal range. Le tumulte à la mâchoire crispée (Tumult with Clenched Teeth) from the same year, and in the collection of the Musée d’art contemporain, is a controlled frenzy of pigment. It is an example of how a plethora of marks can form themselves into a vectored composition, and already indicates Barbeau’s careful consideration of the relationship between gesture and structure, one of abstraction’s central problems.

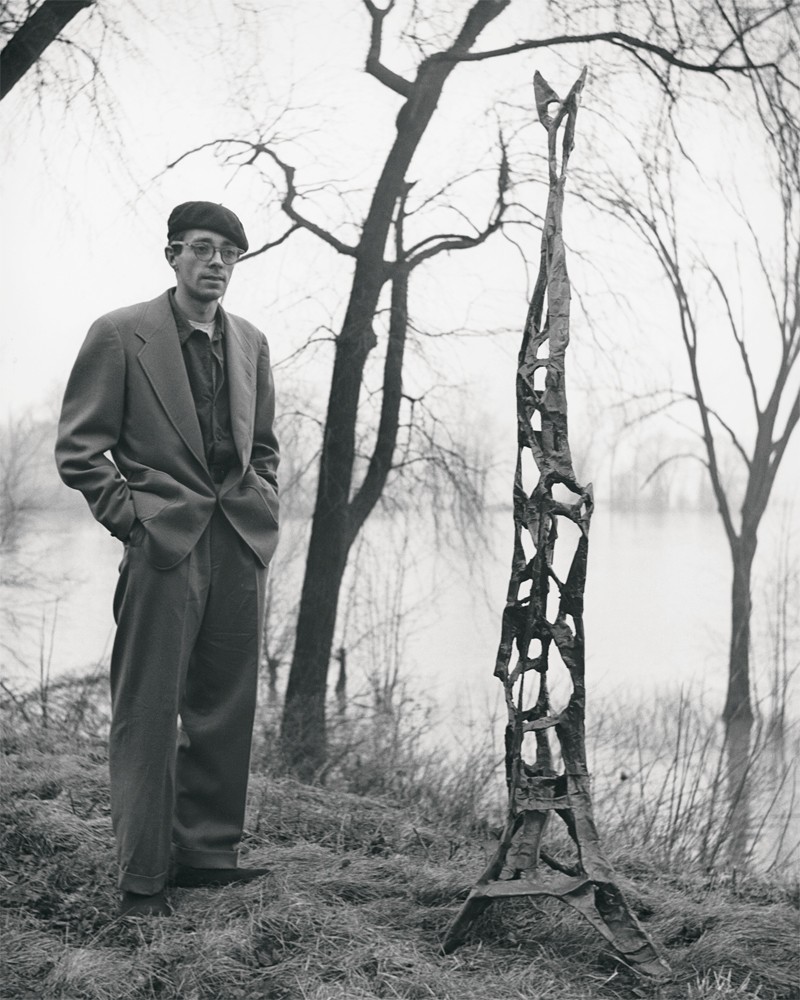

Marcel Barbeau with his papier mâché sculpture, Oblongue étaline (Oblong slack), 1952. Photograph: Maurice Perron. Courtesy the artist.

In this early period, Barbeau was trying out any number of different ways to make a painting. In Sauvage-Furie ou Automne-delire (the title carries a sense of dynamic unpredictability), a small oil made in 1947, the artist uses a palette knife to peal back the painting’s surface to reveal a kaleidoscopic array of colours and shapes. In method and palette, this work is slightly indebted to Borduas. Then in the same year, Barbeau painted a larger oil on canvas called Au château d’Argol (At the Chateau d’Argol), 1946–47, another work in the collection of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. The painting was inspired by the Surrealist gothic novel by Julien Gracq, which Barbeau had read more than a decade earlier. It combines a solid sense of composition with an overlay of linear skeining. Behind the hypnotic black lines, he locates clusters of rich, suffused colour, mostly in red with brilliant turquoise highlighting, as if they were smudges of flowers hanging in some exotic garden. The work effortlessly captures a sense of both movement and form. It’s as if the act of painting were creating a way of spying on the art of painting. Barbeau has orchestrated an abstract gaze, sensual and alert to the necessity of looking.

In 1953 he painted Les cheveux alies jouent a cache-cache by removing pigment that had already been laid down. The work, which means The Winged Hair Plays Hide and Seek, acknowledges a style of European surrealism that includes Dali and Tanguy, but its attraction comes from scratching the canvas to produce the fugitive lines that float across the painting’s surface. A work like Ouvri, made in 1956, a mesmerizing topography of faceted, constrained colour, is a classic example of Barbeau’s “all over” paintings (he is quick to point out the term was never one he used, but was applied by art critics in talking about his work). In 1947 he had made 50 paintings in this style. Three years later in an explosion of creativity, Barbeau painted a series of 350 coloured ink drawings called Combustions originelles. The one painted in Saint Mathias is simultaneously elegant and visceral. Early on Barbeau demonstrated that he had a subtle hand and a special ability to render atmospheric colour.

Prairie naissante (New born prairie), 1956, oil on canvas, 36 x 48”. Photograph: Robert Etchevery. Courtesy the artist.

He describes himself as “a travelling painter,” a term that goes beyond describing his choice to live in a number of different cities. From 1962 to ’74, he resided mostly in the United States and Europe, where he encountered first-hand the most current aesthetic developments in the world of art. His travelling, then, became a sort of aesthetic smuggling, through which he brought back to Montreal whatever applications he found useful for his own work. Barbeau was something of a stylistic magpie, importing examples of the attractive ideas he discovered on his trips and applying them to his own practice. He was able to generate very different looking paintings out of what was essentially a phenomenology of seeing. One painting could be his consideration of a landscape (although the finished painting would never be easily identified as that); another could come out of seeing what cigarette ashes looked like under a microscope.

The Refus global had referred to “the annihilating prestige of remembered European masterpieces,” but Barbeau was discriminating with which masterpieces, and from where, he was prepared to engage. In his employment, their influence is less restrictive than catalytic. Because he was so fluent in the various languages of painterly composition, he has a tendency to accent his work with the visual nuances he has picked up. So you can see the conversation he is having with Jackson Pollock in a number of works (from paintings in the late ’40s to untitled gouache drawings in the late ’50s). In a work like Comme des enfants, 1972, his talk is with Robert Motherwell; in Glissement Abowaskava, 1968, it’s a tête-à-tête with Ellsworth Kelly; in Tumulte, 1973, he has words with Sam Francis.

His engagement with Op Art came out of his fascination with the work of Victor Vasarely. Barbeau’s optical paintings retain an undeniable energy. In a pair of works done in New York, Retine Oh La! La!, 1965, and Retine virevoltante, 1966, you can see his admiration for Vasarely’s optical trickery. But Barbeau was able to tone down the visual hijinx and produce paintings that were very much his own. Much of the later Vasarely now looks dated, but in these cheeky, aggressive paintings, Barbeau comes across as utterly contemporary. If you place his works from the mid ’60s beside the paintings by the New York-based, Canadian painter Karen Davie, working over the last ten years, they would look right at home. The old dog was already aware of the new tricks.

Veillomonde, 1946, oil on canvas, 86.7 x 86.8 cm. Gift of André Bachand. Collection of The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Photograph: Christine Guest, MMFA. Courtesy The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Similarly, Barbeau’s largely pastel-toned paintings from the early to mid-’80s (which used almost no black) are being re-visited in the colour abstractions of the West Coast painter Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun. The point I’m making is a simple one: paintings get made and then remade for different reasons and under radically different circumstances. Painting’s ongoing life proves that successive generations find ways to re-purpose painterly strategies to correspond to current requirements. In this geneology, Barbeau is both an heir and a progenitor.

Change has been his consistent requirement. It is instructive to see which artists he was sufficiently interested in to borrow from, and no less revealing to see which artists held no appeal for him and why. When he was living in Paris, he met Pierre Soulages, one of the major School of Paris and Art Informel painters, but there was nothing there with which he could travel back home. “I didn’t like his work because he repeated himself so much.” Barbeau’s need for movement is pervasive; it has predisposed him to a method of composing where he often de-centres the work, making it slightly off-balance, either in the arrangement of shapes on the canvas or in the ways he disrupts a straightforward read. This disruption can be achieved by varying the direction of the patterning in his hard-edge paintings, or in mixing a number of lines with claustrophobic fragments of colour. On occasion, he has made paintings that are violent in the speed of their execution. The need to find out how movement can effect the way a painting is made developed from his fascination with dance. While he doesn’t know the source of this inspiration, he is fully aware of its presence. He was taken with dance as early as 1947 when he made the principal mask for Dedale, a piece choreographed by Françoise Sullivan, the dancer and painter who was not only a signatory of the Refus global, but a contributor to it as well. Her essay “La danse et l’espoir (Dance and Hope),” 1948, made the same argument for the transformative power of dance that the painters in the Automatiste movement were making for painting. In his painted version of La danse et l’espoir, 1975, Barbeau returns to Sullivan’s title and prefigures the kinds of intense performative paintings he would do with Paul-Andre Fortier in Toronto and Nova Scotia in 1977, and Vancouver’s Anna Wyman Dance Theatre in Montreal in 1978. The piece with Anna Wyman’s company was called Danse frenesie, and there is decidedly something of this frenetic quality in La danse et l’espoir, too. A storm of primary colours, mixed with lavender and teal, creates a dazzle of movement below activating black drips and stutters. It is the visual record of a wild choreography.

Glissement Aboswaskava, 1968, acrylic on canvas, 178.5 x 203 cm. Gift of Jacqueline Brien. Collection of The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Photograph: Brian Merrett, MMFA. Courtesy The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Marcel Barbeau is a sort of painterly forensics expert; he wants to test out how certain gestures, marks and forms work together, and what that interaction tells us about how paintings are composed. So his inquiry into the drip, the calligraphic mark, geometric and irregular shapes, and the line made from dipping a piece of hose in pigment and then striking the canvas with it are all part of his ongoing aesthetic investigation into picture making. The evidence of this inquiring mind is distributed throughout his productive career: in the daring reduction of Nostalgie du pays, painted in Paris in 1962; in the somber energy of Neigeoliale, made in Montreal in 1976; and in the audacious minimalism of Glacial splendor from Montreal in 1988. Similarly, because he worked his paintings from his own small collages, he was also engaged in considering what effect shifts in scale and medium have on what a painting becomes.

In the work he has been doing in the last decade—paintings that employ the richest and brightest palette he has ever used—he is working out the complicated relationship between figure and ground. His accomplishment in this area of abstraction is significant; in looking at these works you undergo confusion in attempting to figure out when a shape slips into the compositional category of being a ground is both perplexing and exhilarating. The eye constantly moves back and forth between determining what is shape and what is colour. The confusion we feel is one Barbeau consciously sets up. He is a consummate problem-maker and a problem-solver. He makes problems because he is so restless, and he solves problems because he is so persistently inventive.

_The following interview was conducted in Montreal by Robert Enright and Meeka Walsh on Thursday, March 25, 2010. _

Sentinelle des ondes (The guard of the waves), 1991, acrylic on canvas, 52 x 74”. Photograph: Robert Etchevery. Courtesy the artist.

BORDER CROSSINGS: Were you only 16 years old when you first went to the École du meuble and met Paul-Émile Borduas?

MARCEL BARBEAU: I was 16 or 17. After you had done primary school in Quebec, you had to choose what you wanted to study, and my mother told me that my father was a very good carpenter and that I should be one too. So she presented me to the Director at the École du meuble and they accepted me. After two years, I had had enough working with wood and that’s when I met Borduas, who was teaching there.

Had you become fairly proficient in working with wood? No. I was afraid of the machines. But I met Borduas when I was passing in the corridor, and I saw this class where people were hollering and talking independently, so I asked the Director if I could be one of the students who were doing painting and he said it was okay.

Did you have any interest in painting? No, I didn’t know anything about it. It was Borduas who told me that I should paint. He must have seen some qualities in me as a painter that I didn’t see myself. He actually preferred my work to the work of Riopelle. He said to Riopelle that you have good technique, but you should do something different, something more personal. Because Riopelle was very skillful and I wasn’t.

What was about it about Borduas that made him so attractive to you? Our relationship was that of a young pupil to a master. That was it. I had the kind of admiration that a dancer would have to his master.

Did he like the kind of relationship between student and master that was based on power? He didn’t say so but I think he liked it.

You start out and he approves of your painting, and then you do a body of work that he very thoroughly rejected. That must have been very difficult for you given the relationship that you had. Yes. He didn’t like that work, but a month later he told me that I should not have said that to you because there were some good qualities in that work. He was moody.

Did you regret destroying them? You see, when you start any kind of work, drawing too, there is a part of what you do that doesn’t fit with your feeling, so you do it but you’re not happy with what you’re doing. At that time I was just starting to draw and paint, and I didn’t know too much about it. What he was telling us was that we had to see the work of great painters, so he told us to go to the library and get books on Miro, Breton and Matisse and Léger. He was always giving us insights into them. He was reading and he knew about all the American painters as well.

Were you on a fast learning curve? I didn’t know where I was. It took time to know the material, and it is very hard to find what you are as a painter because there are so many influences from other painters. But I never felt any competition. It was more like they were friends, and I was trying to know as much as I could about them and about museums. I was just trying to learn. I was also making a lot of drawings at the time. I was using a brush and coloured inks.

What was the atmosphere like around the group that became the Automatistes? Was there a sense of collegiality? It didn’t work exactly like that because we were coming from different educational backgrounds. For example, Fernand Leduc was nearly a priest. His family wanted him to be there. He was in the seminary, but he didn’t stay long. The church didn’t play a role in my life. My mother was not very religious and my uncle had a girlfriend who was Protestant.

How did this group coalesce into signing the Refus global? The one who was pushing Borduas to write the Refus global was Claude Gauvreau, and he revised all the writing of Borduas. Gauvreau was very enthusiastic about it when he first saw it. But Borduas was afraid because he had a family, and he was living in St. Hilaire, a little village, and all the people around him were Catholic.

Did he have an idea that he could loose his teaching position because of the document? Yes. He told us that he would be thrown out. His wife left him and she took the children and all the furniture. He didn’t even have a bed left in his house. It’s very easy to understand why his wife was afraid for her and her children when you know how Quebec was at that time.

Why did you sign it? Because that was the way I was thinking. I realized that what he was saying was true. I didn’t feel there would be repercussions for me because I didn’t have a job and I didn’t own anything. I had nothing to lose. Pierre Gauvreau had just come back from Europe. He was an officer in the Canadian Army, and when he came back to Montreal, he took off his uniform, read the document, and said he was willing to sign it. Marcelle Ferron’s father was living in the country and he was not Catholic at all, so she was willing to sign it.

A number of the signatories were women. Was the group advanced in the way that women were seen? At that time there were a number of women who were very evolved in their understanding of society and they were happy to sign it. Like Françoise Sullivan, whom I knew very well.

You have a painting called Dance and Hope, which is the title of her contribution to the Refus global, and you also made the mask for Dedale, an early piece of her choreography. When did your interest in movement start? I really don’t know exactly when it started but it developed very fast. Everything was very fast because the Refus global was published very quickly and there was a store called the Librairie Tranquille where the Refus global was sold. It was a nice place. I think there were about 400 printed.

Entrailles (Entrails), 1991, acrylic on canvas, 52 x 74”. Photograph: Robert Etchevery. Courtesy the artist.

Did you have any idea that it was going to be as influential as it was? No. We did it and we didn’t know what would happen. Afterwards we were afraid of what it would mean for our friends and our family. We were aware that it would have some impact, but we didn’t know how much. Quebec is like a small, divided village, and you really couldn’t know what would happen or where.

Was there a real cohesion among the members of the group? Was it a tight community of people who had the same interests? No, we met but we didn’t form a group.

When you look back on that period do you have a different sense of it now than you had at the time? Yes, I do. I’m not afraid as I was back then. We evolved with the society around us and we came back into society.

When Borduas left did it cause the group to lose focus? Well, the group operated completely differently when he wasn’t there. We started to exhibit alone instead of trying to exhibit as a group. We started to think about ourselves as individual artists. I had a better sense of what I was doing and I was accepted as a painter.

What was driving you to make so many paintings and drawings at the time? I was exactly like a golfer who just loves the sound of hitting more balls. Painting has a side that is physical; it’s not just an intellectual pursuit.

To see the footage of you painting with a percussionist, you have tremendous energy. You couldn’t have approached all your painting that way. That must have been specific to the performed paintings? You see, I worked a lot with dancers. I just loved the relationship that exists between painters and dancers. I’ve worked with them several times, from Vancouver to Toronto. It’s hard to be happy. When you are alone in your studio you are really alone. That’s one of the reasons why we exhibit so often. You’re trying to make friends and I proposed to work with dancers because it took away the solitude.

What relationship did the two art forms have to one another? They are both about movement, and the human relationship between the dancer and the painter is very important. When I paint I never look for an emotion. But the forms in the painting will get together and nearly make love; the forms want to live together. This is what happens in the relationship you can have with dancers: it’s part of what I would call love. A painting is completely voluntary; it’s based on a certain rhythm and repetition of that rhythm, but it is voluntary. I see the relationship between one form and another; I don’t look at the end of the process. I do it one by one by one by one.

What is it that makes you produce a painting that is about colour and form as opposed to one that is more about mark making? It’s always intuitive. I wanted to push the repetition of the same form all over. I would take a lot of pleasure at the end when I could see what I had done.

You used the word “all over.” You were doing work like that very early on. Critics have used that word but not me. I never described my work. If you want my work described, you go to my wife.

But even if you didn’t use the term, that becomes an important juncture in the history of painting. What gave you the freedom to make that kind of a painting? The freedom is in yourself. You see, you’re on the golf course and you have all the tools to hit the ball as far as you can, but you can lose it. It’s the same thing in painting. You want the thing to be as strong as it can be, but you can miss it.

Were there colours that you thought were yours? My preferred colours are the bright hues; but it’s not just the colour itself, it’s the background. In a painting it can be the pale blue that makes the other colours pop out. I use a lot of blue.

Would you build the shapes before you put in what becomes the ground? The background is made after. I don’t know what colour the background will be before I finish the front colours.

You went to Emma Lake, the summer workshop in Saskatchewan? Yes. Frank Stella was the workshop leader. It was funny to see the way he was working. He made all his paintings with just one coat and he was always on his knees.

When did you first separate out areas by using masking tape? In the ’60s in New York City I started using tape. American painters were using it too. I was in New York when a lot of the major American painters were around. I went to the Cedar Bar and Franz Kline and Pollock were there. They were always drinking. I was drinking a little but not the way they were. The problem was that when you asked them a question, they wouldn’t speak to you because there were so many people after them. I asked Kline some question about his work, and he said, I’m not talking here; I only talk in the studio. But you could see their work in the galleries. I went back to New York in the ’70s and stayed for a month or two. Oddly, when I was in Paris it was very hard to speak to people.

Did French painters have any influence on you? The one I liked the best was Vasarely. I was very friendly with his son, whom I had met in New York before going to France. Then when I was in Paris we would see one another.

Printemps (Spring), 2009, carylic on canvas, 48 x 48”. Photograph: Flip Image. Courtesy the artist.

You seem to be an artist who is always open to improvisation and to movement. Is that how you think of yourself? For me art is a question of not repeating the same thing and also a question of having fun. If I feel too alone in my studio, I get on a train or a plane and I fly somewhere.

So travel was a way of charging the batteries? Yes, I like to travel.

How have the places you’ve lived and painted in effected the art you have made? The place interests me, and it shows in my variations and the colours I use. I’m a kind of travelling painter. My painting does not change a lot when I spend only a week or two in another place. But I will take everything from that place and bring it back to Montreal. If I see something strong, I just love to take it back.

Do you have a good visual memory? Is the discovery always in the making rather than in discovering what a space is like? I can say that I have borrowed a sense of colour harmony from a lot of people who have been presented to me. There are painters who give us a memory of something that has happened before. You don’t forget what you have seen or learned from them. I think all painters or writers have to have a sense of memory of what they have done before in order to be able to go on to something else. When I do a painting I have about 10 or 15 paintings all around me. I always have 10 canvases ready to paint. The procession of colours can change every week. I don’t have a certain colour that I like; what I like is the relation between colours.

What makes you continue to make paintings? I really don’t know. I would have to ask my psychiatrist.

There seem to have been times in your life when painting was very hard on you. It’s always hard to do anything in life. The young skater who won first prize at the Olympics looked beautiful and what she was doing was fantastic. But there were 12 years of practice behind what we saw. For a painter, it’s the same thing. Time counts as experience. It gives you a background. There are a lot of different senses of intelligence. Some people are very, very bright, but they would never be able to do a painting.

What about your gestural memory? The gesture doesn’t count at all. It’s what you see in front of you. It’s what you accept. Because a move that you have probably done hundreds of thousands of times is just a mechanical gesture. It helps you to put down the material. The memory is there. You don’t have to speak about it because the memory is inside of you. You cannot change it, it’s there. Also, I didn’t tell you this before, but for all the paintings I have made in the last 15 years I have made collages. They are working notes from which I’ll develop the painting. I make 15 or 20 collages, and from them I choose the one I like the best.

Does the shift from the small collage to the scale of the painting always work? I know that it will be different, as will be relations between the forms and the shape. I photograph the collages, and then I project the photograph onto the canvas. To make the collages I cut and glue paper. I use an Exacto knife. Then I trace the shape and tape it off. I take the images from news magazines, and I ignore the writing that is often on the collage fragments. In my next show, I’ll present all these things as part of the show. This gives me a certain amount of freedom when I make the painting because when I project it, all the forms are there and I just have to paint them. The colours change from collage to painting as well. I make the decisions based on feeling.

The relationship between some of the shapes in the collages is almost sculptural. How do you make a decision about what form of art you take? For me everything is related to my painting. It is very hard to put it into words. It’s easy for my wife because words are part of her philosophy. She can explain things in words, whereas I can’t. The collages come from painting, and they get transformed in the travelling. But these collages gave me a very good idea about what the new paintings would be because I have a choice of forms. It is very hard to find in yourself the energy to make new forms.

Is the transition easy to make from two to three dimensions? I have made it several times, and I think now I have produced nearly 20 sculptures, some eight to 10 feet high. The problem with sculpture is money. It costs a lot of money to make them. And you have to pay the workers, so you have to be wealthy just to be able to do one sculpture or one commission. Sculpture for me is more form than colour. There is some sculpture where I just want to play with the form. I use slides and I project them on to the wall. First, I take the measurement, and after that I’ll go to a foundry and show them my drawings, and from the drawings they’ll make the sculpture.

La clarté du plaisir (Brightness of pleasure), 2006, acrylic on canvas, 59 x 59”. Photograph: Daniel Roussel. Courtesy the artist.

I’m struck at how useful a tool photography is for you. Yes. I first started projecting in the ’50s. I worked for a photographer, and he said if you want to work for me for two weeks I will give you a camera. That was when I started doing my own photography.

Was Danse et l’espoir about a ground that you would then play with as if you were dancing on the surface? At that moment I was discovering a little bit of what Pollock was doing. I was also influenced by other painters in Europe. But I wanted the kind of freedom that he had. I saw a film on Pollock where he was using a cord, which he dipped into paint, and so I did the same thing. I would splash the painting with it. I didn’t like the movement of the wrist as much as the cord. I knew the work of Pierre Soulages, and I had met him but I didn’t like his work because he repeated himself so much.

One of the things that characterizes you is that you don’t want to repeat yourself too much. You travel through your own styles of painting. You say you like the kind of painting that comes out of the collages because it offers you more freedom. Freedom is just something that you like to do. The search is for freedom.

What sense do you have of your achievement? I can’t answer that. Somebody else would have to give you that answer, someone who has more distance. I’ve worked for more than 50 years. But it’s not pride that comes to mind when I look over the work. I did it because I had the need to do it. I’m not better than anyone who is doing something else. I had no choice. We think we have a choice, but we don’t.

You’re doomed to be a painter? Yes. I’m caught.

Are you still discovering things? All the time.