Zin Taylor

Zin Taylor’s work has always been erudite and literary, often using bits of obscure or speculative art history as a conceptual frame to generate multifarious “total works” that can incorporate drawings, sculptures, photographs, performances, videos and texts. This dispersed, referential and narratively-driven approach is something Taylor shares with a number of other Canadian artists of his generation, such as Gareth Moore, Geoffrey Farmer and Derek Sullivan, all of whom also share Taylor’s penchant for meta-artistic and quasi-museological practices of collecting and arranging objects. For all these artists, intellectual tricksters like Marcel Broodthaers and Martin Kippenberger cast a long shadow, but that shadow might fall heaviest on Taylor, who has produced an exhibition and a book based on the work of the former (The Crystal Ship, 2008) and a quasi-fictional documentary video about the latter (Put Your Eye In Your Mouth: A conversational documentary recording Martin Kippenberger’s Metro-Net Station in Dawson City, Yukon, 2007). Naturally, such reference-laden and formally complex work can be a bit daunting for the uninitiated—even sometimes for the initiated. Writing in The Globe and Mail, critic Sarah Milroy memorably branded a 2005 exhibition by Geoffrey Farmer as “too abstruse for youse,” and it’s a charge that could conceivably (if not necessarily fairly) be levelled against any number of Taylor’s fascinating but often baffling works. It’s worth mentioning that, despite occasionally puzzling audiences at home, Taylor, Farmer, Sullivan and Moore have all found warm reception in Europe, especially in the Netherlands and Belgium—Taylor relocated to Antwerp in 2007 and has been living there since.

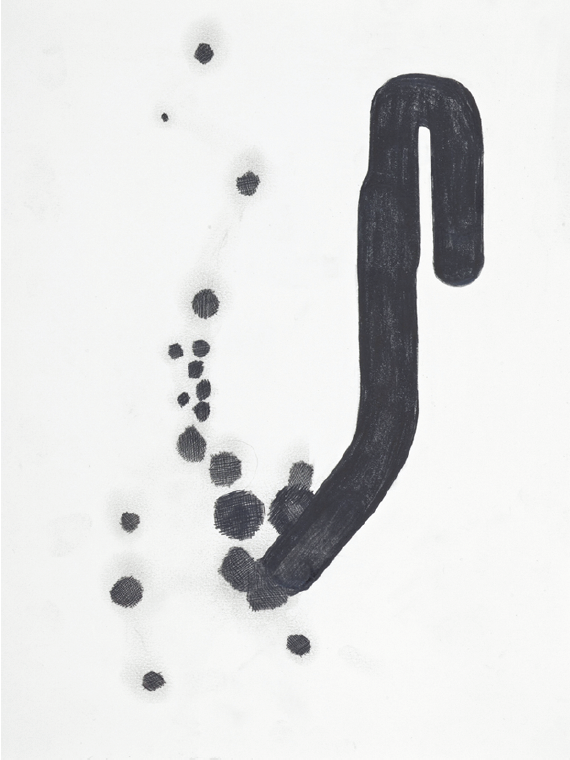

Zin Taylor, The Story of Stripes and Dots (Spots Made by a Line Touching a Surface), 2012, graphite on paper, 35.7 x 27 cm. Images courtesy Jessica Bradley Art + Projects, Toronto.

By this point, I may have given you the impression that Zin Taylor’s art is dry or boring, or that he is intent on intimidating viewers with an overload of arcane knowledge. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth. What has always been most seductive in Taylor’s work is the oblique relationship he develops between objects and concepts. Things, for Taylor, are never merely vehicles for meaning, screens on which to project signifiers, or documents of factual occurrences. Rather, form for him is equally a property of matter and ideas, and translation between the two realms is both eminently possible and essentially mysterious. Thus, Taylor’s favourite metaphor for the artistic process is one of organic growth in which the artist, the raw materials and the script or narrative each have their own unique agency. Accordingly, the objects that Taylor produces (or sometimes finds) operate as relics or artifacts. There seems to be a deliberate process of occultation at work in which the relationship between the form at hand and the source material it derives from become obscured. Taylor can then assume the role of archaeologist or anthropologist (perhaps one from a distant future), presenting objects of unknown function but suggestive of mystic powers, hidden agency or biomorphic vitality.

This anthropological fascination with the primitive or primordial (a clear debt to Surrealism) in Taylor’s work has increased as his reliance on scripts and references, particularly art-historical ones, has waned. This is not to say that Taylor’s production of texts has slowed—recent publications like Growth, 2011, and Plants Do Things, 2010, prove otherwise—but rather that his concerns are becoming more fundamentally formalist. Thus, his recent exhibition at Jessica Bradley Art + Projects, “The Story of Stripes and Dots (Chapter 2)”—a sequel to a first chapter presented earlier this year at Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst Antwerpen in Antwerp—takes two of the most basic units of abstract art as its subjects. Remarkably, this transition to more abstract preoccupations has rendered Taylor’s work lighter, more playful and ultimately more accessible.

Stripes and dots, in this show, are both pattern and form. As Taylor writes, “A stripe seen from head-on is a dot, a dot seen from the side could well be a stripe.” Entering the space, one immediately encounters this idea in three dimensions in the form of A Structure to Filter a Room (Two Snakes and a Dot), a kind of hanging, Calder-like mobile made of two long, snaky forms (one painted black with white polka dots, the other half-black and half-white) and one black sphere. These shapes, rendered somewhat crudely in plaster, exude a childlike charm as they rotate gracefully, suspended from the ceiling. This monochrome simplicity extends to the other works in the show, which include drawings, more sculptures and photographs of sculptures floating in space. In each of these, elementary forms—mostly abstract lines, dots and stripes plus a palm tree and a snail—bounce and bump as if in an animated cartoon. Reminiscent of Philip Guston’s paintings or lumpy Brâncus,i sculptures set upon by stray Buren stripes, the suggestive, organic curves of these works also call to mind surrealist sculpture without the existential angst. Titles like An Alphabet of Ooze and the Shadows They Make nod towards the notion of base Materialism, and Diagram of a Knife, with Memories evokes darker associations, but Taylor remains the wry conceptualist: his interest in subterranean fundamentals and originary forms is philosophical, not psycho-sexual.

A Structure to Filter a Room (Two Snakes and a Dot), 2012, plaster, plastic, paint, dimensions variable.

And what sort of philosophy are we talking about? You might call it a kind of flat ontology in which ideas are things and vice versa. In a text for Artforum and an exhibition last year at Ursula Blickle Stiftung in Germany, Taylor elaborated his concept of the unit. “Units,” he wrote, “are what exist in physical space after the thinking and abstracting settles into shape.” Elsewhere, he also wrote that he sees each element of the Structure to Filter a Room as “taking a position, as a thought or opinion on a subject unnamed.” Likewise, in the wood-and-plaster appendage that is A Haze of Influences Choreographed Into an Arm, we see that Taylor only choreographs this haze of influences, which apparently has both mind and matter of its own. By focusing on the form of thought rather than its content, as well as its murky implication with materiality, Taylor hints at the limitations of words for grasping reality. If we want to continue the conversation, perhaps we should try thinking like a thing—an artwork, perhaps. ❚

“The Story of Stripes and Dots (Chapter 2)” was exhibited at Jessica Bradley Art + Projects, Toronto, from March 24 to May 5, 2012.

Saelan Twerdy is a Montreal-based writer and a doctoral student in the department of Art History and Communication Studies at McGill University.