Wyn Geleynse

The exhibition “A Man Trying to Explain Pictures” by Wyn Geleynse, which premièred at Museum London in the artist’s home town of London, Ontario, could as easily have been titled “Pictures Trying to Explain a Man.” The majority of the works in the exhibition are in fact moving pictures: film and video loops, many presented in sculptural contexts. Through their repetition of images of play and the performance of speculative social actions, or their presentation of a masculine subject in what are often compromising situations, the works implicate viewers in the sometimes uncomfortable project of working out an explanation for the man. Among the most compelling aspects of a viewer’s experience here is the need to question our role in what are often unholy rituals dedicated to knowing the self—in this case, the self of a middle-aged white male and, possibly, the self of the artist.

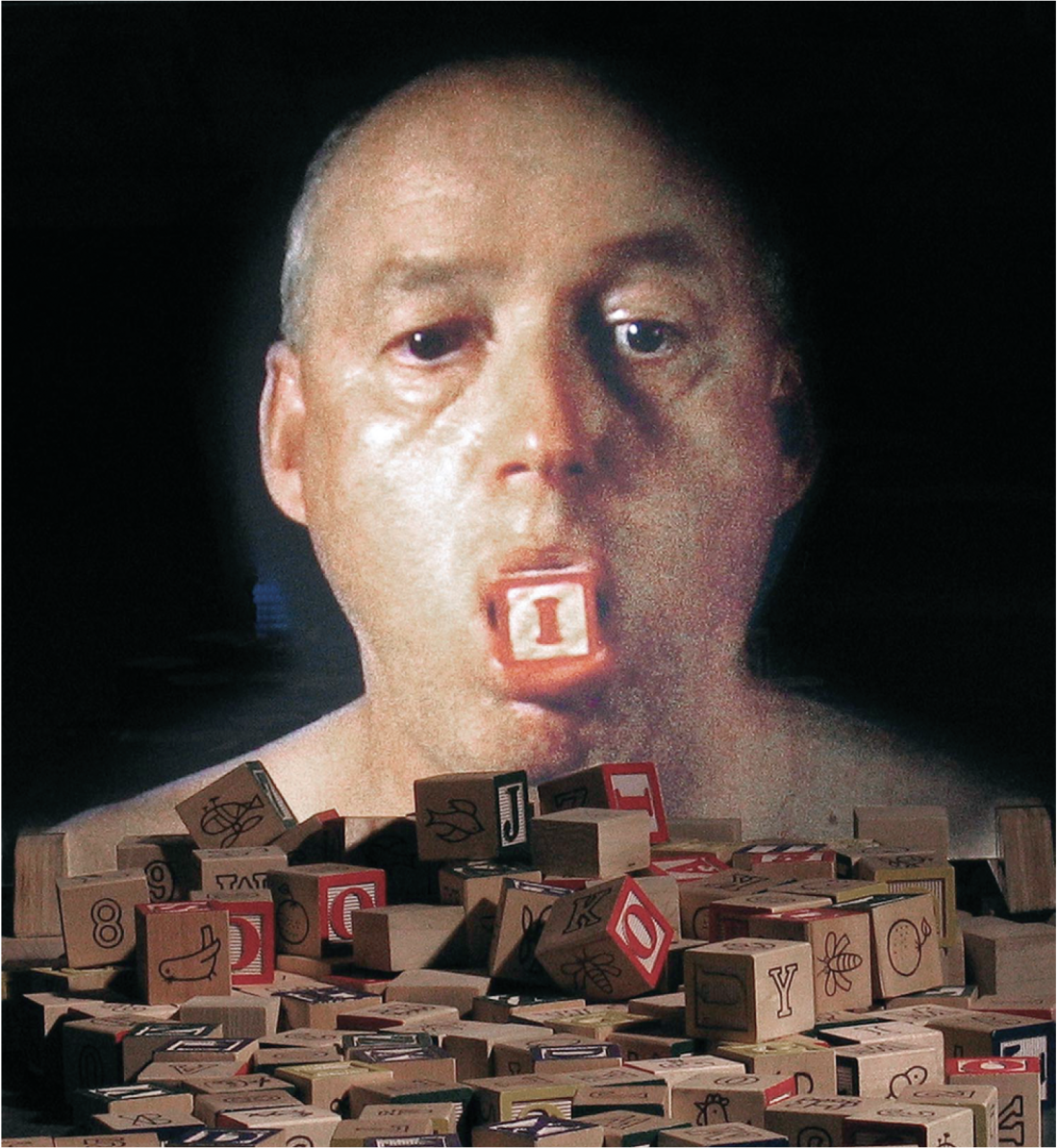

Wyn Geleynse, Just … , 2002, DVD video projection and audio, ground glass, lettered blocks, 1/3. Courtesy TrépanierBaer, Calgary. All photos: Wyn Geleynse.

In works such as The Slack Wire, 2002, we are offered a spectacle whose sensibilities hover between the elegance of a filmed mime and the casualness of home video. In this piece a tiny, glass-based, projection screen suspended on a flexible cable shows a fellow, portrayed by the artist, playing clumsily as if he were a high-wire performer. The work is by turns metaphoric and oddly unadorned, and somehow becomes profound through its familiarity. The man explaining himself in pictures alternately entertains and discomfits us, but the question remains: does he need us to be there in order to do this work? Is an audience required so that he may try on the many selves we encounter here—in other works the artist plays Pinocchio, a dunce and a head that spits blocks that never make words—or ought this to be strictly a private matter?

The issue of how modern and contemporary art works lay claim to our involvement in the enterprise of negotiating the other’s self has been a familiar and important one for several decades. In light of this, I recall seeing a work by American filmmaker and photographer Lorna Simpson several years ago and being struck by the experience of feeling both empathetic to, and distant from, the life challenges of an Afro-American, middle-class, professional woman. The experience reminded me that such representational art often allows viewers to operate both within it and outside it at the same time. In Geleynse’s work, the tension between identification and distance is palpable. What is most materially startling about this tension is the fact that it is regularly manifested through the use of projections on tiny groundglass screens suspended in front of film or video projectors. In such works, the screens act like two-way mirrors that allow viewers access to a seemingly private performance, while the semi-transparency of the projection surface acts as a cue to acknowledge the presence of onlookers on the other side of the glass. This is especially the case in I Want More Than This, 1995, where a giant 1950s-era photo of a boy is “crowned” by a suspended projection showing a man’s hat wobbling as if it is not quite ready to be worn. Geleynse suggests here that inasmuch as the act of trying on what it is to be a man might regularly happen in private, it can never fully happen there if the self is to fully exist in human society.

Wyn Geleynse, Sometimes … I Don’t Think I’m Smart Enough to Survive, 1982, 16 mm projector, 16 mm film loop, stool, timer, hand coloured photograph. Courtesy TrépanierBaer, Calgary.

Wyn Geleynse’s exhibition contains other sculptural projection works and two single-channel videos, many of which pose further questions about a man. A tiny, recent video installation, Lisboa, 2003, is a depiction of a middle-aged male (in this case, not the artist), reciting a monologue about himself and his relationships, which is projected onto a small, painted wood screen. When the projector is operational, the image of the man appears to be caught between two sets of windows, as if within a narrow glassed-in vestibule. At the end of the sequence, the projection fades for a short time and the wooden screen can be seen to have been painted to enhance the quality of compressed visibility the operational work displays. This two-stage experience, whereby the time-based image and the constructedness of its mode of presentation are assembled and dissembled before us, astutely comments on the ways the subject of the video tells on himself. His words and actions simultaneously reinforce and deny each other. This work is less invested in the question of the audience’s position in “making the man” than some of the others here, and more in showing us how readily an artwork might unmake itself and its subject at the same time.

In “A Man Trying to Explain Pictures,” the idea is masterfully presented that to claim a place in the world, he must show himself in public in the knowledge that he will always invite scrutiny. Clearly, this subject has been a constant preoccupation in works by Geleynse for a period of almost 20 years. Ultimately, the exhibition shows the artist arguing forcefully for the necessity to extend one’s self into society (sometimes with great vulnerability), and, in so doing, be met by others. ■

Wyn Geleynse, “A Man Trying to Explain Pictures” was exhibited at Museum London in London, Ontario, from September 17, 2005, to March 26, 2006.

Patrick Mahon is an artist, writer and educator who lives in London, Ontario.