Would the Real History Please Stand Up

Ron Frohwerk, in his thoughtful catalogue essay, conceives of this exhibition as a self-conscious critique of the familiar notion of history as a “seamless trajectory.” Attacking the authority of such a notion is, by now, a venerable enterprise of modernism. History is “reclaimed” by those artists and writers who restore it to what we accept as its true condition of shreds and shards. Earlier centuries added arms to Greek statues; modernism took them off again. However, this accreditation of the fragment can come dangerously close to being simply another “look,” just another intellectual picturesque—Benjamin’s cultural landscape of ruins. Even disruptions of the notion of wholeness, or of a recoverable history, have to struggle now to seem authentic. That authenticity lies in the simulacrum of history that each artist makes. The simulacrum casts doubt on its own possibility, as well as on the possibility of “History.”

In Bev Pike’s work, history is autobiographical, indicated by the empty bed and bedroom. In some works a leg protrudes, an impersonal synecdoche of human presence and identity. The protruding leg also suggests limbs emerging from rubble after a disaster, so the weight and abundance of bedding has a vaguely disturbing quality.

There is a sumptuous feeling to the rumpled bed, and the central subject, a quilted comforter, does call up the “powers of woman to create and nurture,” as Frohwerk suggests. However, the comforting element of the comforter is only one aspect of this strong work. The quilt itself is composed of scraps of things that in an earlier incarnation, as clothing, were part of other lives. The quilt, overrun by seams, operates analogously to the making of history. On the whole, the work gives an impression of alienation and isolation. Retreat to a room may be read as reversion as well as security, and the acts foregrounded by the subject matter—quilting, bedmaking, lovemaking—as obsessively repetitive. In an otherwise rich, loose, mixed media drawing, Chambre de Chaleur, there is an ironic atavism of technique. Sparkles are glued to the butterflies of the quilt and these trashy, glittery, little markers conjure up children’s artwork, simple instant gratification and wish-fulfillment, fantasies in keeping with such simple bedrooms. In all, Pike’s work offers the illusion of the sensual and tangible. At the core of autobiography, the work is a metonymy of the consolation of those memories by which we try to regain and rewrite our own history. But she also exposes these memories in their capacity for deception: the bed, the room, is somehow unpeopled, unattained.

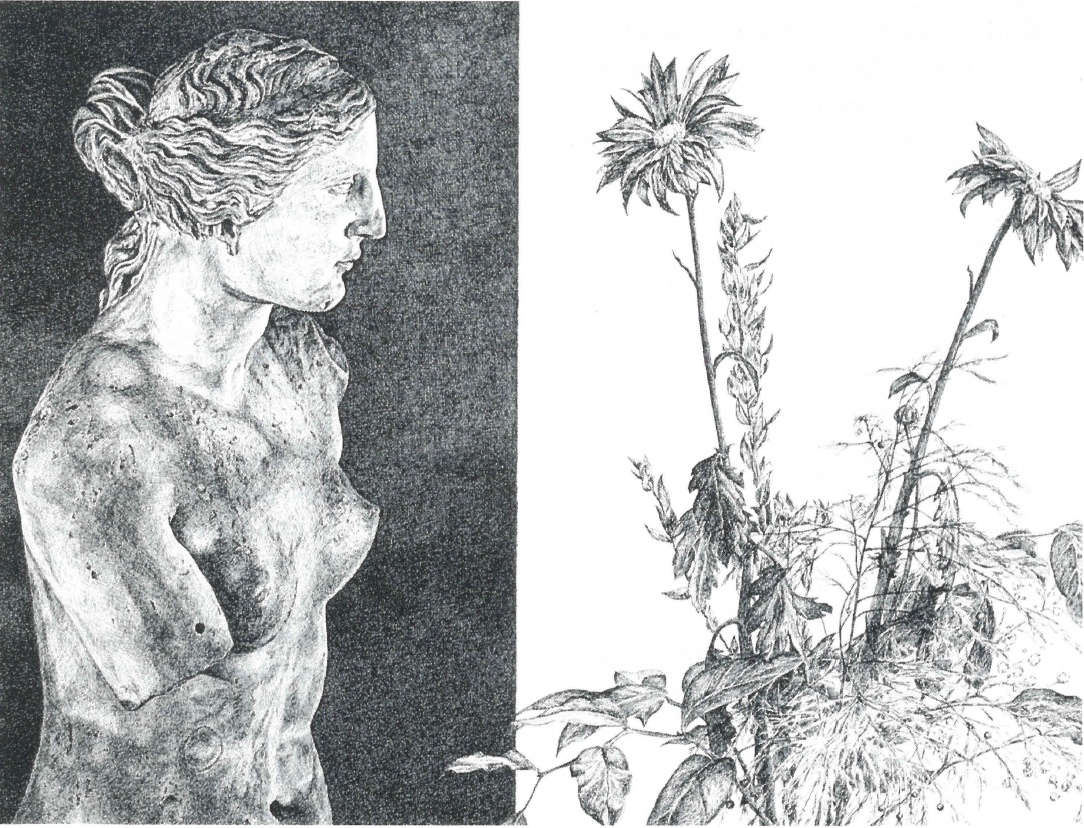

Steve Gouthro, Venus and Fleurs, 1989, pen and ink, 56.5 x 76 cm.

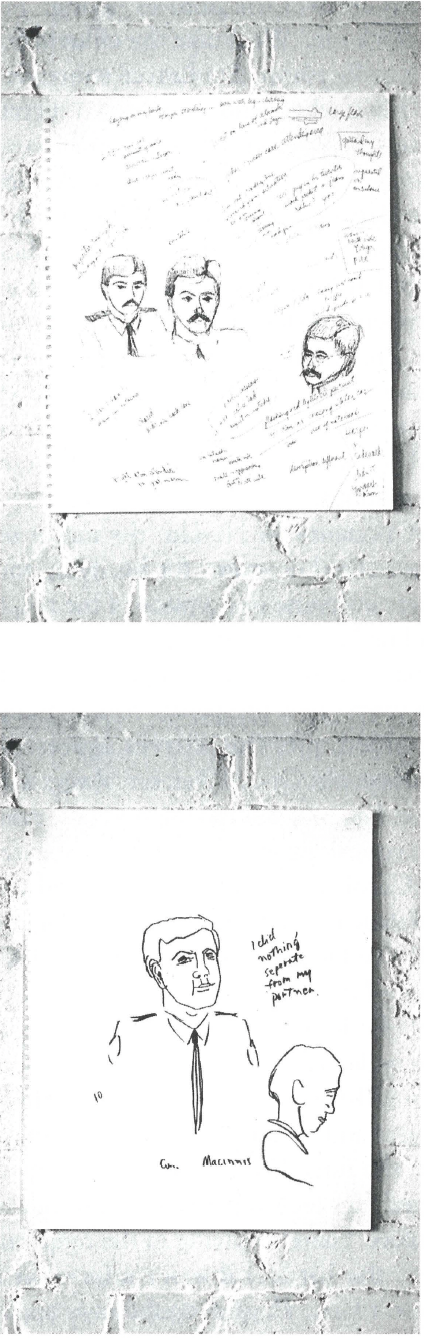

Jeff Funnell’s “narrative” is the police shooting of Cree leader J.J. Harper in Winnipeg in 1988. In constructing his socio-political history in Notes from the Inquest, Funnell assumes the role of courtroom artist (the one who produces the strangely wooden drawings that provide the only visual information about court proceedings broadcast or printed by the media). These images forcibly remind us that our knowledge of the judicial process is constructed and that the facts, even the truth that is the ostensible end of the process, are equally constructed.

Funnell enacts a parallel accumulation of evidence—crude drawings, jotted fragments of testimony—without aiming at any single conclusion. The objective discourse of the law (especially as it is recorded in the literally seamless transcription taken by the court reporter) is made deliberately paratactic and cryptic. For example, ballistic information and minor technical measurements, whatever their accuracy, seem meaningless as random jottings without context. Clichéd phrases taken from the objective testimony (“pool of blood”) are revealed suddenly as having an astonishing emotional content and an inherent bias. Further, it is not clear whether Funnell as court reporter records only what strikes him as significant, or whether his reporting is just random sampling. And what if the courtroom artist, whose sketches we see on the news, were no longer interested in the primly histrionic “characteristic” pose or expression of the courtroom players? Funnell’s deliberate crudeness, his paradoxical refusal to describe, foregrounds the slickness of the media marketing of such causes célèbres. Funnell’s account produces neither a glamorous fiction nor an alternative to it.

What’s exposed are police racism and the flaws in political and judicial authorities. But Funnell is not naïve enough to offer art as a “truth,” either. The very procedures set up for investigating institutional flaws (the original inquest into the Harper death turned into the larger Aboriginal Justice Inquiry, generating a thousand testimonies) also are exposed for evading responsibility by spawning sub-institutions; and these would have to include Funnell’s piece. It is a parallel structure that can by its mimicry only distort, but not remedy. The video component of the piece is a “re-enactment” of the death struggle of Harper and the policeman. All that we get, even in reality, are simulacra. Even the crazily well-lit, clinical pantomime of the struggle has its suspect aspect, as Funnell shows us: like wrestling, it is “good TV.” Ultimately, the gross violation of justice is lost irretrievably in the system. Funnell’s pieces suggest not only the impossibility of absorbing the infinite data of historical fact, but also the difficulties of short-circuiting the chain of events.

Jeff Funnell, J.J. Harper Inquest, April 1988, pencil and ink on paper, 35.6 x 43.2 cm.

Steve Gouthro’s prints and drawings combine irony and pathos in effective mutual contradiction. To use his own kind of incongruity, it is as if we had Walter Benjamin at the Epcot Centre, guiding us through enactments of other cultures and histories while, at the same time, denying that they can be retrieved. Gouthro takes up the “great man” (that term being used here ironically) mode of teaching history. The mythic figures of our cultural history—Napoleon, Oedipus, Madame Curie, General Wolfe and J.J. Harper—are time-travellers turned tourists. The irretrievable past is represented as an alien landscape in which famous people register the shock of the unassimilably new.

Gouthro’s Napoleon in Egypt, in the orientalist romantic tradition, contemplates the illegible hieroglyphs of that “lost” civilization. Madame Curie is surrounded by the skulls-as-souvenirs of the Mexican Day of the Dead. Oedipus, who foregrounds our culture’s psychoanalytic mythologies, is in Las Vegas; polyester-clad, elderly, he strokes a Sphinx which has the bosom of a Playboy bunny. The possibility of understanding past events is limited irremediably by our own cultural point of view, just as newly discovered landforms perplexed European explorers. Madam Curie’s X-rays may reveal the actual skeleton, but she has no cultural apparatus for assimilating the folk rituals of death represented by the carnival skeletons.

In other drawings, the cult figures of the modernist avant-garde are caught out as poseurs. Our romanticized, even sentimentalized history of the great artists of modernism (their alienation, their suffering) is questioned. In Brendan Behan Contemplates His Liberty, the épater les bourgeois stance of the antisocial, drunkard poet is caricatured as he makes a grotesque face at a souvenir statuette of the Statue of Liberty. Lotte Lenya, young, dark and melancholy, the very type of the avant-garde, returns to George Grosz’s Weimar Berlin of magnates and prostitutes (itself a caricature), aloof as Hamlet among the Toons. Gouthro’s virtuoso emulation of Grosz’s drawing style adds to the strength of the incongruity, reinforcing our awareness of cultural history as pastiche. The radical social critique of Grosz, Brecht and Weill in the 1920s and 1930s becomes just another novelty, another “look,” a stylish commodity, according to Benjamin’s analysis of Weimar society.

Frohwerk concludes that “these artists view the recovery of history as an indispensable vehicle by which human autonomy can be reclaimed in the present.” These investigations also show that we can retrieve history only in a limited way, by irretrievably changing it, and that the autonomy to be gained by the process will always be contingent. ♦

Elizabeth Legge is a freelance curator and art historian living in Toronto.

The Recovery of History: Jeff Funnell, Steve Gouthro, Bev Pike Extension Gallery, Toronto, February 1991, Curated by Ron Frohwerk and Jon Tupper.