Women’s Work: The Radical Domestications of Aganetha Dyck

How do you take ideas from the world of art, modify them and make them your own? What is influence, what is derivative? The question of influence and its relation to personal innovation is a central concern and a source of inspiration for Aganetha Dyck. In her work we see both environmental influence, in the use of found objects, and also inspiration from the world of art ideas.

In at least one instance, Dyck intuitively experimented with a form of expression simultaneously being used by artists in major centres in the USA. Walking Winnipeg’s streets in 1977, Dyck found five or six Polaroid photos that had been run over by a car, squeezing the emulsion and producing a fascinatingly altered image. At home she tried to duplicate this hit-and-run process by alternately freezing and ironing her own Polaroid photos, unaware that Lucas Samaras and others were at the time doing similar work. Much later, she saw their work in the book One of a Kind: Polaroids by Artists.

Photography by Ernest Mayer.

Particular periods in art history generate their own particular constellations of artistic ideas, and in our contemporary world of instant communications technology, artists in many centres may deal simultaneously with ideas that are ‘in the air’, and come up with similar artistic statements. In writing of Iain Baxter working in relative isolation in Vancouver in the 6os, Lucy Lippard says, “NETCO’s (Baxter’s corporate nom de plume) ideas … often coincided point by point with those unpublished projects in the planning stages in New York and Europe at the time, with which the Baxters could not have been familiar. The points of departure were, of course, the same (Morris, Nauman, Ruscha, etc.) but the spontaneous appearance of similar work totally unknown to the artists can be explained only as energy generated by these sources and by the wholly unrelated art against which all the potentially ‘conceptual artists’ were commonly reacting.” Lippard notes later that certain artistic sets of ideas become current “as the result of general conditions of prevailing style and thought patterns, but the provincial artist cannot get his information to others fast enough for its impact to be felt … consequently, the original artist in isolated areas often comes out looking derivative.”

Cabbages, 1978

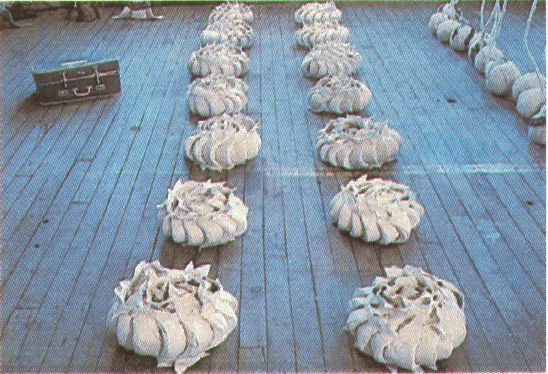

Close Knit, 1976-1981

This question of the recognized authenticity of innovation has been of concern to Aganetha Dyck, and indeed to many artists working and living in Winnipeg. It is really not a question of authentic artmaking, but a question of who has the power to authenticate creative innovation in the making of art. This power is believed to be exclusive to large art centres.

At the beginning of her career, in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, Aganetha Dyck made art in a totally intuitive way, largely without technical training and totally innocent of the history of art. Her first introduction to the wider world of art ideas came when artist George Glenn was appointed by the Saskatchewan Arts Board to the position of Artist-in-Residence in Prince Albert in 1973. He brought with him a collection of books on art. Aganetha shared his studio space and while she immediately began to learn from his teaching, she was hesitant about approaching the collection of art books. She remembers that she worked up her courage, and the first book she dealt with was on Picasso. With this tentative introduction to art history, the troubling question of influence soon surfaced. At the time she was engaged in a personal discovery of the artistic possibilities of variously wrapped bundles. Glenn introduced her to Christo’s works, and as a result she stopped making her wrapped works, thinking that it had “already been done”. Looking back on that period, she now recognizes the validity of those early explorations and is saddened about not fully following them through.

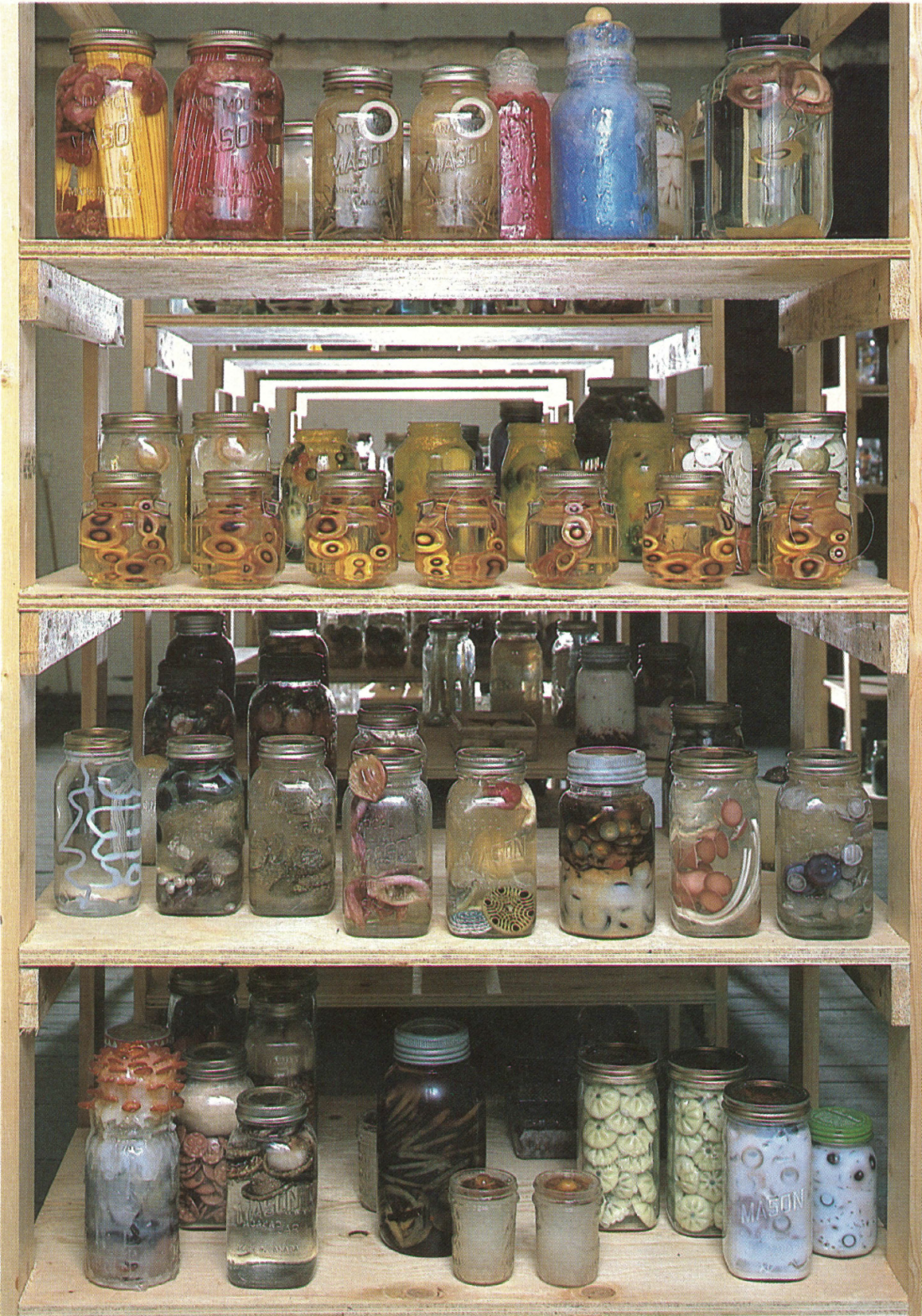

Shelf, 1983

In many ways other than the introduction of art history, Dyck is grateful to George Glenn for his early instruction. She credits him with introducing her to “the ideas of the necessity of having a body of work, and of not being in too big a hurry to exhibit”. Another important mentor in this early period of development was Margaret Van Walsem, a weaver who used primarily Navajo and Salish weaving techniques. She also shared joint studio space with Glenn and Dyck in Prince Albert in the early 70s. She generally encouraged Dyck in her artistic pursuits and taught her Navajo and Salish weaving. Although Dyck persevered for two years, she came to feel that she was temperamentally unsuited to the demanding techniques and meticulous approach necessary for weaving. She produced only one completely finished work in two years. At the time, her real creative interest was taken up with a chance discovery of the process of felting. Another student weaver had accidentally shrunk fleece while washing it in preparation for learning the art of spinning. For a weaver, the shrunken fleece was useless, but Dyck was fascinated by this matted object.

Installation shot. The Winnipeg Art Gallery. 1983-1984.

At home, a little hesitant about admitting her strange activity to her studio associates, she began to deliberately shrink fleece, excited about the sculptural possibilities of the resulting soft, tangled forms. At the time she was unaware of the utilitarian uses of felting in places such as Afghanistan, where the process had been devised as a way to make woollen clothing even warmer. Her interests were wholly aesthetic, but when she got around to showing her creations to a few other artists, she recalls that they were met with scepticism. The objections seemed to centre around the issue of technical control: “Well, yes, these are interesting, but can you control this process?” Margaret Van Walsem, for one, encouraged Dyck to forget about the demanding weaving techniques and to continue with her felting explorations, but the question of technical control still disturbed her. Since her knowledge of traditional art techniques was limited, her initial solutions came from the area of ceramics, a field in which she had some experience. She began to devise techniques to reproduce, in felt, shapes common to ceramics; she made felt cups, plates and jars. By making recognizable objects she could demonstrate a degree of control. From her knowledge of slip-poured moulds, she began making fabric ‘moulds’, stuffing them with wool and then shrinking them in the washing machine with hot water. This was a long, laborious process, so Van Walsem suggested knitting pre-formed cups and saucers and then shrinking them. Kniting was also frustratingly slow, so Dyck began collecting second-hand woollen clothing as raw material for making sculpture. This remarkable idea proved a turning point in her work and provided a fertile field for several years.

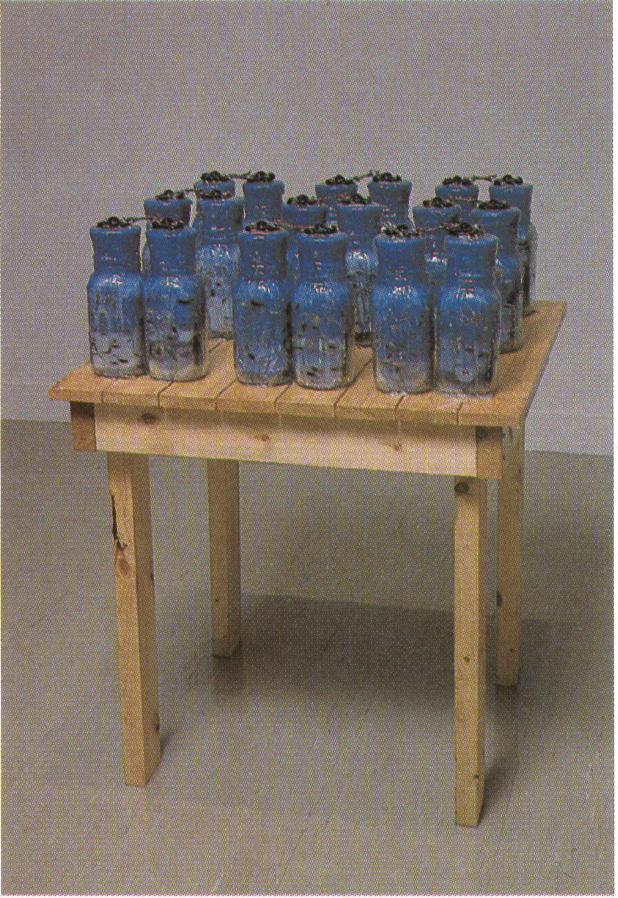

Canning Table, 1983-1984

Initially, she felt guilty using anything that could possibly be of real use to anyone as a garment, so she would only deal with discards. “I just couldn’t handle the innuendos that I was wasting time and good material.” In 1977 she applied for and received a Canada Council Explorations Grant to experiment with the felting of sheep fleece, but even then she felt that her real interests lay with the shrunken clothing.

In 1978 a move into a new studio space in Winnipeg added, by chance, another element to the development of Aganetha Dyck’s work. The previous tenant had been a clothing manufacturer, and from him Dyck purchased a collection of thousands of buttons and clothing fasteners in an immense range of shapes, sizes and colours. She purchased it instinctively, not knowing what role these objects from the real world would play in her work. The buttons formed part of the studio environment, to be unconsciously assimilated while she continued to work on her shrunken clothing.

There were by now, a large number of felted clothing works and she experimented with ways to exhibit them. Assemblages came first, with trial-and-error building of closets and containers—a great deal of searching for the proper way to introduce these pieces into an exhibition space. Assemblages, without wooden supports, were exhibited at the Arthur Street Gallery, Winnipeg, in 1979 under the title Sizes 8-46. She experimented with boxes, but the old uneasiness about influence caused her to reject boxes as being too derivative of the work of Lucas Samaras and Joseph Cornell.

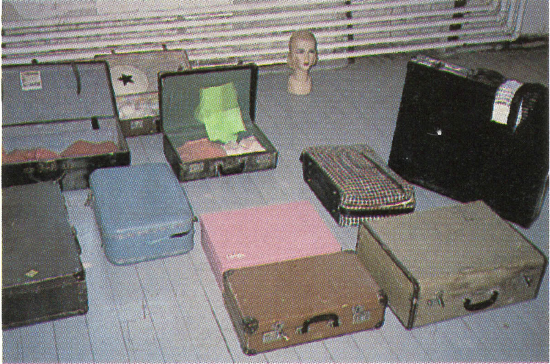

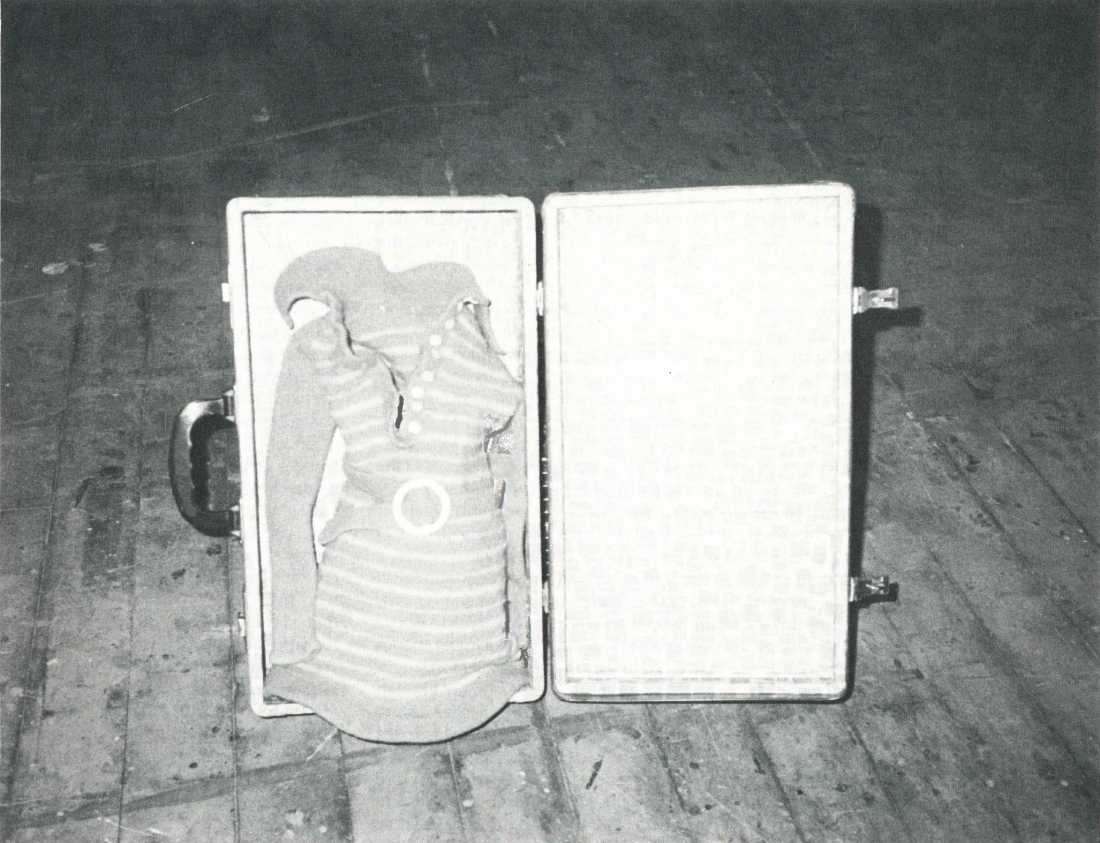

23 Suitcases, 1981

23 Suitcases, 1981

The solution came to her as she set about shipping a series of the felted clothing sculptures to the Norman MacKenzie Gallery in Regina as part of a Prairie Artist Series in 1979. She packed some of the pieces in suitcases as a convenient method of transportation, and the idea of an exhibition of suitcases originated. Some of the buttons also found their way into the suitcase works, and the idea of incorporating found objects grew from the inclusion of the buttons. In the end, most of the material in the suitcases was purchased from sources in the vicinity of her studio, including the Big-4 Store on Main Street, auctions, booths in Market Square and second-hand stores. Friends also contributed materials as they became aware of the nature of her work. The associations between felted clothing and found objects became more and more dreamlike and surrealistic, the framing of the suitcases marking the boundaries between the everyday world and some other level of consciousness evoked by the contents of each valise. The suitcases were shown in an exhibition simply entitled 23 Suitcases at Saskatoon’s A.K.A. Gallery in 1982.

When the button collection came into Aganetha Dyck’s possession, the buttons were stored in old cardboard boxes. In choosing the buttons to be used in the suitcase pieces, these boxes often broke, so she put many in the type of glass jars used for home canning. As the buttons in jars became part of the studio environment, the idea began to develop of really enclosing them in jars by subjecting them to home canning processes. The idea of transforming the buttons, both physically and functionally, by subverting a homey utilitarian process, amused and delighted her. Eventually the buttons and clothing fasteners were processed in multiples by canning and deep-frying, while others were simply covered with acrylic medium and placed in jars. Stacked on wooden shelves like the contents of a well-stocked pantry, these were exhibited at the Winnipeg Art Gallery in August, 1984. Dyck now considered the work of other artists working in similar idioms, and found that she was able to deal with the question of influence in a more enlightened way. A talk by Liz Magor, when she came to Winnipeg as part of the Canada Council Visiting Artists Program, was particularly inspiring. Magor discussed and showed slides of her pressed clothing sculptures, as well as her piece Time and Mrs. Tiber. This is an open set of shelves, seven high, stocked with home-canned fruits and vegetables, and found intact by Magor in an abandoned homestead after the death of Mrs. Tiber. Magor commented, “In her house I found a shelf full of preserves that Mrs. Tiber had put up. She was working against time … The preserved fruit remains, but she and her husband are dead. I had heard people talk about Mrs. Tiber, but when I saw those jars I really felt her presence.” Magor has given Mrs. Tiber’s canning a different meaning by changing the context of the wooden shelves and jars of preserved fruit. She shifts the emphasis from physical survival to evidence of physical existence, and to meditations on human mortality. Aganetha Dyck has manipulated the process of canning to make a different reality, in which canning is not really canning. The buttons have been transformed and take on a new identity, while still reminiscent of their previous existence.

Italian Knit, 1981. Photography by William Eakin.

Another artist whose work was considered by Dyck in relation to her own was Victor Cicansky. He had also exhibited jar-shaped multiples, replicas of home canning, made of fired and painted clay. Cicansky, inspired by archeological discoveries of ceramic votive tomb offerings, presents images of home canned food as slightly wacky, off-centre replicas of the everyday world. By contrast, Aganetha Dyck depends upon nonverbal associations and intuitive connections in her creative process.

Despite her concerns and fears to the contrary, Aganetha Dyck has dealt successfully with environmental and art world influences to create a personally innovative and exciting body of work. Her position as an artist in Winnipeg however, makes it difficult, as Lippard noted, for the work to win an audience in larger centres. This is a fact of life for all Manitoba artists and indeed for thousands of artists in smaller cities and communities everywhere. Terry Smith, writing about the Australian art scene in the periodical Artforum, offers insights relevant to the experience of artists here in Winnipeg. He comments on a “a bad case of double standards” affecting artists in provincial centres. If the provincial artist is judged by standards which are set in the major centres, “the artist invariably loses.” If he is judged by local standards, “he might win too easily.” Smith goes on to say, “If the local artist and his audience take the metropolitan/provincial dichotomy as fundamental, it often seems that nothing but this shuttling between standards can go on until, by some miracle, the local art world itself becomes a metropolitan centre.” There seems no way around the fact that as long as strong metropolitan centres like New York (and we could add Toronto) continue to define the state of play, and other centres continue to accept the rules of the game, all other centres will be provincial, ipso facto. As the situation stands, the provincial artist has no choice other than to be provincial. How can we in Winnipeg succeed in awarding ourselves the power to validate the authenticity of our own art? Smith suggests that we resist “the authoritarian assumptions of superiority …. Instead, we should look to the benefits that would accrue to all from acting in a way which projects our own uncertainties and fallibilities undisguised and which values the differences of cultures relative to ours.” In 1984 we are all plugged in. The ideas that are ‘in the air’ are, indeed, in the air above New York, Toronto, Winnipeg, Moose Jaw and we may dare even to add, Rat Portage. ♦

Sheila Butler is a Winnipeg artist and writer. Her work was included in the Manitoba Artists Overseas exhibition which is travelling to London, Paris and Brussels.