William Kentridge

William Kentridge’s work circulates around power, exploitation, human hardship, love and grief. The work is visually and emotionally connected to his home city, Johannesburg, South Africa, and viewers can experience Kentridge’s art aesthetically, emotionally and intellectually, without previous knowledge. In many ways his oeuvre is suited for creating a sense of universality, an art that has curators writing: “This matters to all of us.”

The extensive retrospective show in Kunstmuseum Basel Gegenwart, and the performances and talks around it, were the must-go-to events during Art Basel this year. In Amsterdam his most recent opera, The Head and the Load, created in 2017, began the 2019 program of the Holland Festival, and, shortly after, his second solo exhibition opened at the Eye Filmmuseum. The unique style of his work, which is almost always based on charcoal drawings that he uses as palimpsests, with a high tendency to thematic and stylistic repetitions, has the viewer trace both shows unmistakably back to their maker, even if the curatorial concepts of the two shows are fundamentally different.

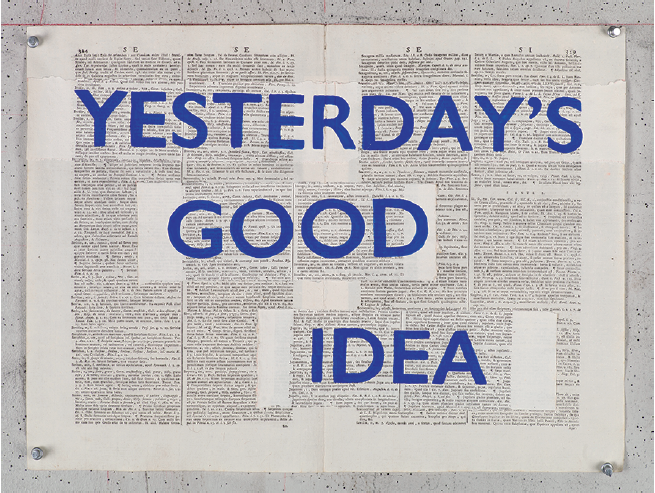

William Kentridge, Blue Rubics, 2016. © The artist. Image courtesy Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel.

The film series “Ten Drawings for Projection,” 1989– 2011, on which the current exhibition at Eye Filmmuseum was centred, was donated by Kentridge after his first solo show there. Both exhibitions at Eye Filmmuseum were curated by Jaap Guldemond. Black boxes create a logical visual path from one film to another, avoiding headphones and making the show a continuous and collective experience, immersing viewers in the strange worlds of the fictional characters, Soho Eckstein and Felix Teitlebaum, both middle-aged white men.

Eckstein embodies the insatiable evil of capitalism. He is a greedy man who decides on the life and death of the Black mine workers in his employ. Teitlebaum is Eckstein’s ever-nude, innocent counterpart and rival. In Felix in Exile, 1994, Teitlebaum is worried about South African identity after apartheid. Isolated in his shabby hotel room, Felix cannot see the protest marches, violence and massacres happening outside. Nandi, a Zulu woman, appears in the mirror and connects Felix with the outer world. She is the only Black individual in this series who otherwise schematizes the native population mostly in the form of anonymous mobs. In the end Nandi dies and her body disappears into the landscape, soon to be forgotten, as are the lives and stories of all native Africans in Kentridge’s drawings.

In Soho and Felix, Kentridge’s fragmented self is being reflected, a white South African man who is deeply hurt by the injustice in his country even as he and his family were successful in this unequal system—which is why his position remains a dilemma.

In 2016 Dana Schutz exhibited her oil painting Open Casket, 2016, at the Whitney Biennial. The painting was influenced by a famous photograph showing the dead African-American boy Emmett Till, who was brutally killed by white supremacists in Mississippi in 1955. The photograph of the tortured body lying in an open coffin testifies to the extremely violent outburst of white men against an innocent Black boy and became emblematic of the human rights movements in the US. In Schutz’s painting the boy’s face is completely unrecognizable, even abstract. Many Black artists were offended by this work done by a white woman. The deeply felt accusations were that Schutz’s painting exploited human suffering to intensify the aesthetic expressiveness of her work. With the abstract painting the boy is deindividualized, which can be seen as a trivialization of his death and the symbolic power of the photograph. Since Schutz enjoys human rights herself, this work was considered disrespectful to those who are still fighting for equal recognition.

William Kentridge, O Sentimental Machine, 2015, in installation view, “10 Drawings for Projection,” 2019, Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam. Image courtesy Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam.

Kentridge’s work has been rarely criticized, even if his many portrayals of native South Africans are ethically problematic. It seems as if his family background made him widely immune to critique. He is a third-generation Lithuanian Jew living in South Africa. His prominent parents fought actively as lawyers against the apartheid system; a system that victimized and dehumanized the Black native majority, a process visually repeated in Kentridge’s drawings. Here, moving dots stand for indistinct crowds, protestors or nameless workers. We see dismembered Black bodies, male heads floating under the earth or filling shelves and fields, and more abandoned bleeding or fragmented corpses lay in the exploited and destroyed mining lands. The native women are figured in Kentridge’s films as muses, beautiful but powerless— nude women holding babies and singing songs of grief and misery, the images reinvigorating the exotic eroticism of African women in modern art. The fact that Kentridge’s imagery is fully accepted in the art world shows that we are living in white patriarchal capitalism where Black bodies continue to be colonized. “Recognizing rather than fixing reality” is how Kentridge interprets his own work, but is it possible that through the aesthetic exploitation of Black suffering, he fixes the ideology of white supremacism instead of recognizing it?

The attention in Basel was on the presentation of the work; the show’s curator, Josef Helfenstein, created an exhibition massive in its scale and novelty and focused on the originality of the artist. Helfenstein titled the show “A Poem That Is Not Our Own,” a phrase taken from Kentridge’s opera The Head and the Load, 2018, which appeared in the exhibition in the form of an installation. The work deals with World War I, which, contrary to conventional knowledge, as the artist clarifies, began in West Africa, where many Africans were recruited to fight for French, English and German armies in return for freedom and equality. In spite of the fact that millions of African soldiers, workers and civilians died, these promises were never realized. In the opera’s plot a group of African soldiers moans about the war they fought for others. Since the main topics of the retrospective are migration, flight and diaspora, “a poem that is not our own” could also describe how the international and especially the Swiss audience (living in one of the wealthiest and socio-politically most enclosed countries) experiences an exhibition where the subject matter is so foreign to them.

In the 1980s Kentridge’s stop-motion technique, based on black and white charcoal drawings, became his stylistic signature, and it has been praised for its methodological uniqueness since the films entered the global art world at DOCUMENTA (10) in 1997. In the last 10 years his performances, theatre plays and operas have been shown all over the world.

Kentridge’s work is not about power and exploitation in the universal sense but rather about separating white from Black identity in South Africa. His art is artistically and intellectually influenced by European and Russian artists, writers and thinkers. Kurt Schwitters is one of his common sources, with Schwitters’s song poem Ursonate, whose “non-sense” Kentridge uses “to produce sense.” However, power and inhumanity are not absurd but real, as Donald Trump or Jair Bolsonaro prove. The Ursonate, 1923–32, the production of a German artist who was excluded from most Dada groups in his time because he was decisively unpolitical and egocentric, does not illuminate colonialism and the ruins it left behind. Kentridge’s performance of this poem, accompanied by slides of paired images projected behind him, is indeed questionable.

Undeniably, Kentridge’s work, especially his operas, have great aesthetic moments. However, the way he visualizes native South Africans and Black suffering, combined with his admiration for the original and processual qualities of early modernism, which are evident in his body of work, is a problematic aspect of his work that cannot be swept away as easily as charcoal drawings. ❚

“William Kentridge: A Poem That Is Not Our Own” was exhibited at the Kunstmuseum Basel, Gegenwart, Basel, Switzerland, from June 8 to October 13, 2019.

“William Kentridge: Ten Drawings for Projection” was exhibited at the Eye Filmmuseum, Amsterdam, from June 3 to September 1, 2019.

Teresa Retzer is an independent researcher, critic and curator based in Amsterdam. Her research focuses on contemporary art, art after the Internet, media theory and critical historiography.

To read the rest of Issue 152, order a single copy here.