William Kentridge

This past May saw the presentation of William Kentridge’s print series “The Nose” at Barbara Edwards Contemporary in Toronto. In 2010, Kentridge was commissioned by New York’s Metropolitan Opera to create a unique staging of Shostakovich’s The Nose. The significance of these Kentridge prints is that they were produced as he worked through his ideas for the opera and his emerging vision of its production. He found the process so satisfying and its generative possibilities so rich, he continued on with the series after The Nose was first presented at the MET.

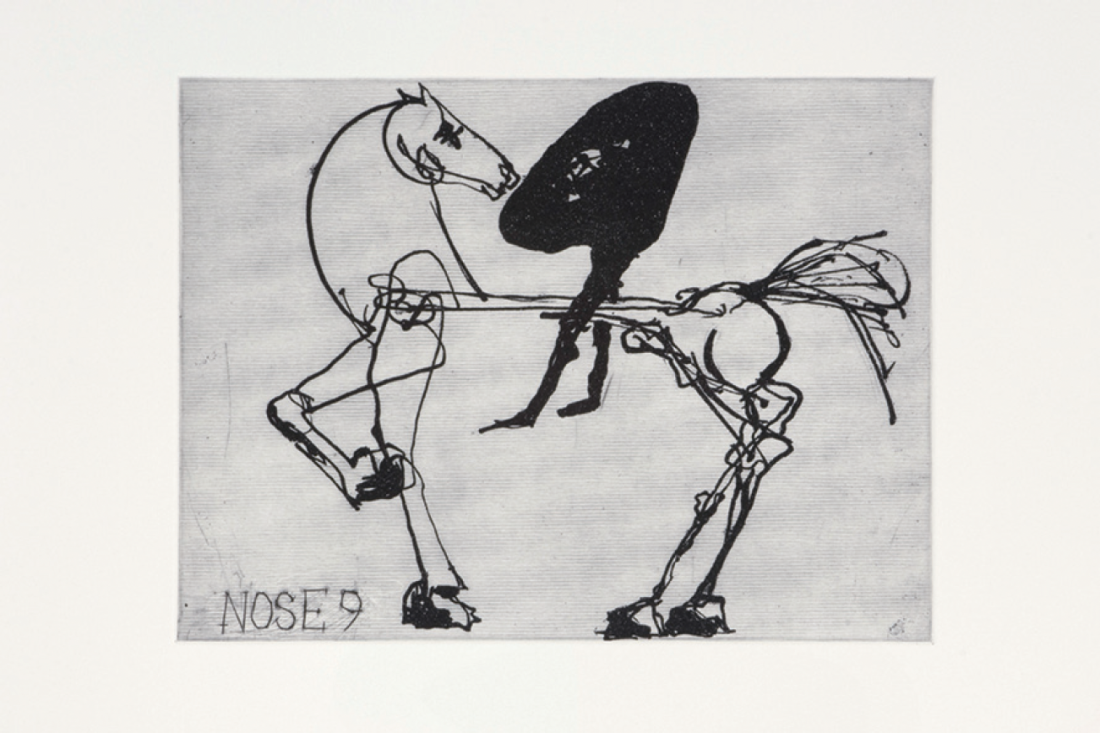

The Shostakovich opera comes from Nikolai Gogol’s short story, circa 1835/6. Gogol’s story itself was inspired by Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, 1759–67, which in turn was inspired by Cervantes’s Don Quixote, 1605. Kentridge, well aware of this history, takes full advantage, placing the Nose on its adventures, sometimes upon a horse, bringing the references right back to Cervantes. Although erudite, beyond question, Kentridge doesn’t display his scholarly knowledge within his figurative work; instead he plumbs it like a dreamscape.

William Kentridge, The Nose Opera (Nose 9), 2008, dry point, sugar lift, aquatint, 13.7 x 15.7 inches, edition of 50. All images courtesy David Krut Projects, Johannesburg/New York and Barbara Edwards, Toronto and Calgary.

Slavoj Žižek is one of the most popular cultural theorists of the moment; he can also be among the most misquoted. It’s just so easy to slip him in there. As his public persona increases, so too it seems do critical barbs. In that sense, he’s a bit similar to Kentridge. Many stand in awe of the intellect and talent, and as popularity grows, so can resentment, and Kentridge’s previous Magic Flute production had received some cautious criticism. Despite, or perhaps because of, its wonderful animations and a questioning of scientific investigation and the Modernism that fed a misguided idealism, as well as its alluding to the massacres of Namibia, the fast moving projections and mathematical diagrams were said by some to distract from the music. Right. Eye roll. What opera needs is less spectacle, even one that might infer serious inquiry into history, with sophisticated imagery.

“The Nose” series expands on many of Kentridge’s themes and this tale of the bureaucrat and his missing nose is the perfect choice for one of his favourites—the self, literally divided. Žižek’s book, Violence, his treatise on the differentiation between subjective and systemic violence, provides some valuable insight into what Kentridge explores and even includes some interesting points on art and opera. An important supporter of Kentridge has been European curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, who has had discussions with Kentridge about Adorno’s assertion that to write poetry after Auschwitz would be barbaric. Zizek brings up the same Adorno quote in Violence: “It is not poetry that is impossible after Auschwitz, but rather prose” and “…poetry is always, by definition, about something that cannot be addressed directly, only alluded to.” Kentridge often mentions his mistrust of certainty in the creative process. Transformation and indeterminacy are the major pillars of his studio practice, one that involves tearing, fragmentation and recomposing. His model or method is a morphogenetic one. Workshops in both Johannesburg and New York, interspersed with lengths of time in the studio and the print shop, ultimately formed around a constructivist model, his marriage of drawing and collage as the perfect stage that alludes to the Russian Revolution, the later Stalinist purges, back to Robespierrean France, and forward to colonial Africa, time swishing to and fro.

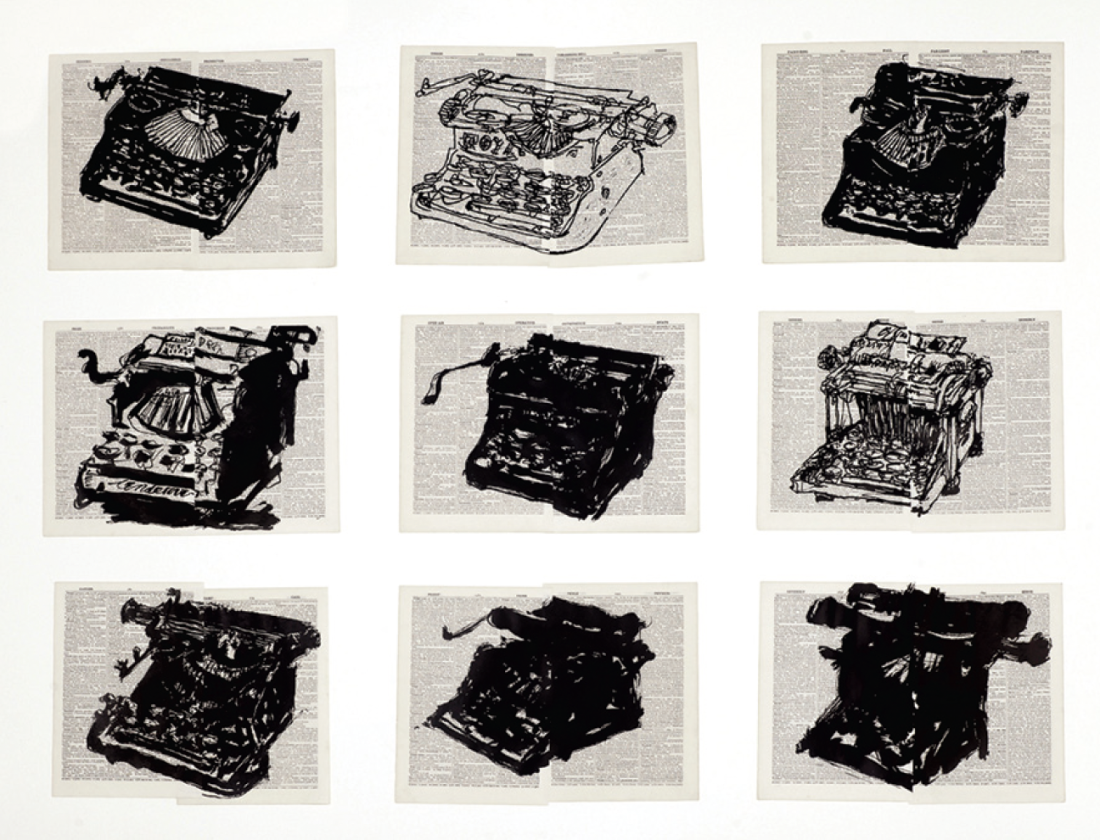

William Kentridge, Universal Archive (Nine Typewriters), 2012, linocut on non-archival pages from Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 43 x 57.6 inches, edition of 20.

If there is a theme we can pull from Kentridge’s Nose opera and the prints, it’s a wariness of emancipatory violence. Just like Tatlin’s Tower, which features in the print series “Tatlin’s Ghost,” there are emblems of failed utopian aspirations. His Majesty, Comrade Nose is another standout with its very loose design sourced from El Lissitzky. The temperamental and extremely fussy nature of the printing plates could make the medium an odd choice for Kentridge. But in fact it’s exactly right in that it doesn’t hide the stages of his endless process and mark making, so heavily indebted to indeterminacy. Kentridge revels in it with works such as Bad Disguises II, illuminating his erasures, traces and ever-shifting, collage-like methods of composing.

Sugar lift is a printing technique that enables a positive image to be made on a plate. The process, thin and delicate, involves plate biting, where acid is used to incise the surface. Picasso’s Satyr Unveiling Sleeping Woman from 1936 is a good example. Essentially, the sugar lift aquatint is an etching where imagery is painted on a copperplate with a sugar solution. As a means of managing value through aquatint while controlling shape through brush marks, sugar lift is almost the perfect etching process for Kentridge in that it allows him to meld his act of writing with drawing. Again, he’s collaging imagery with his written script, his dry-point line work on the copperplates enveloped in a quality of velvety soft richness. The process produces a clean, hard-edged line, but all the visual information lies on the same plane on the printed paper. Nose 24 is a perfect example of this.

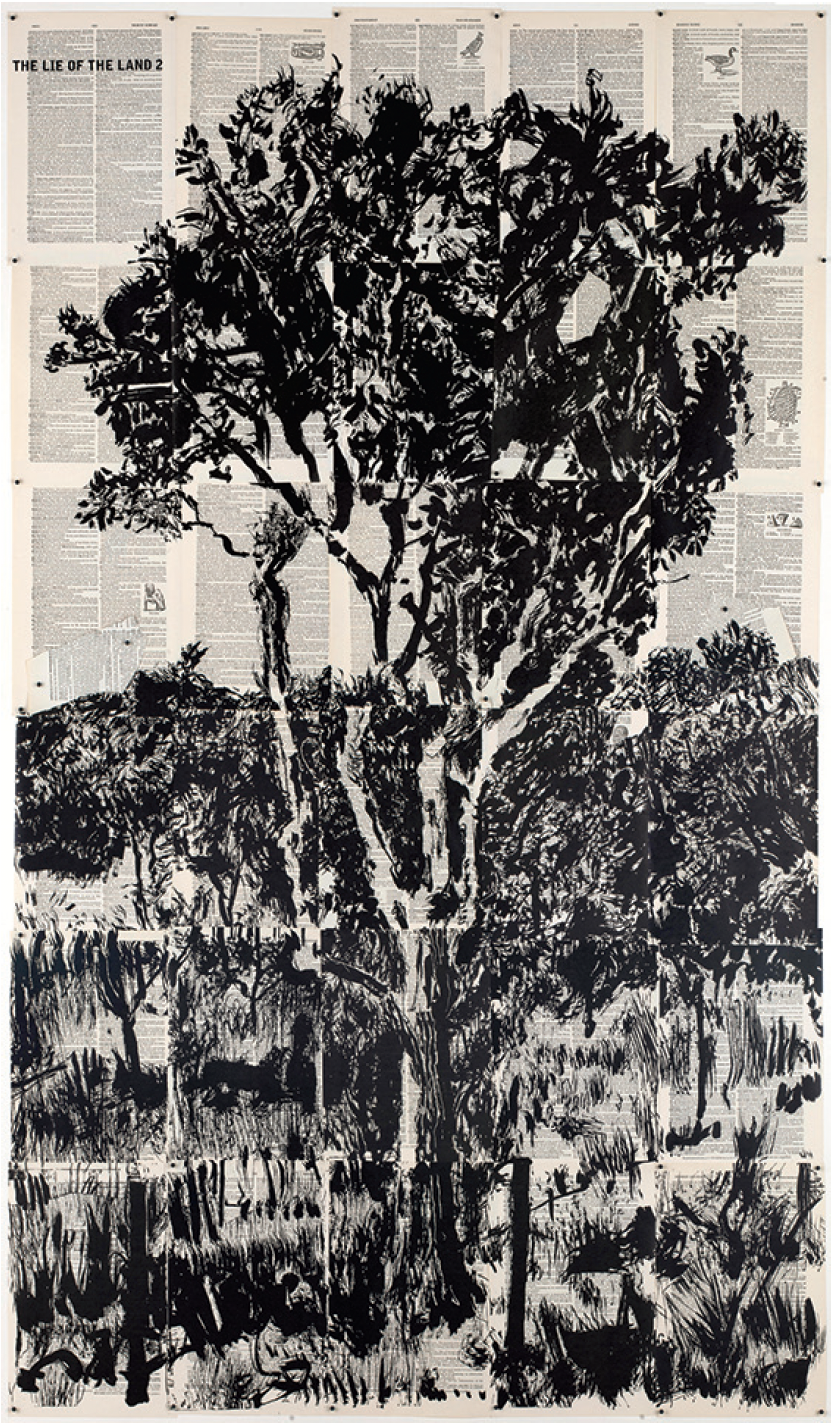

William Kentridge, Lekkerbreek, 2013, linocut printed on no-archival pages from Britannica World Language Dictionary, mounted to Arches, 67 x 42.5 inches, edition of 24.

Barbara Edwards’s presentation of Kentridge’s “Nose” series moves to Calgary this autumn and is further expanded with the inclusion of works from his “Universal Archive.” Here, his small ink drawings were transferred to linocuts and printed on pages from dictionaries and encyclopaedias. It’s another example of his play with meaning and possible transformation, where he further explores the intersection of drawing with lexicography. It could be just another case of an artist at play, intent with his drive to, as he puts it, “keep certainty at bay.” ❚

“William Kentridge” was exhibited at Barbara Edwards Contemporary, Toronto, from May 2 to June 28, 2014.

Matthew Carver has shown his art internationally at venues such as the 12th Cairo Biennale. He has taught painting at the University of Waterloo and the University of Ottawa, among others.