William Kentridge

William Kentridge is an artist whose work—expressive, large-scale figurative charcoal drawings, hand-drawn animated films and theatrical installations—haunts the memory. And like memory, it dips in and out of narrative flow, punctuated by searing images and fugues of engaging abstraction, vibrating between the tonal languages of oppressive brutality and merry whimsy. He told catalogue contributor Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev that, working in his home city of Johannesburg, his artistic goal was to try to “recapture a moral terrain in which there aren’t really any heroes, but there are victims. A world in which compassion just isn’t enough.”

In service of this moral terrain, Kentridge has deployed some of Modernism’s great absurd characters. Beginning early in his career as visual artist and actor, Kentridge used Alfred Jarry’s infantile despot Ubu, who unleashed his unregulated appetite at the expense of those around him, to express the brutality of apartheid. In the films and drawings of Ubu Tells the Truth, 1997—a title that itself is rather absurd—the obese tyrant wreaks havoc while a large live-action eyeball sputters and stares as if in disbelief. Shown with this work in the gallery that was designated “Occasional and Residual Hope: Ubu and the Procession” is Shadow Procession, 1999, a relatively simple film showing black torn-paper figures parading one behind the other across the screen. The film is one part of the retrospective, “William Kentridge: Five Themes.” What starts as a light-hearted romp transforms into the stumbling flight of refugees and the seemingly endless pageant of horrors aired by guilty parties to South Africa’s legendary Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

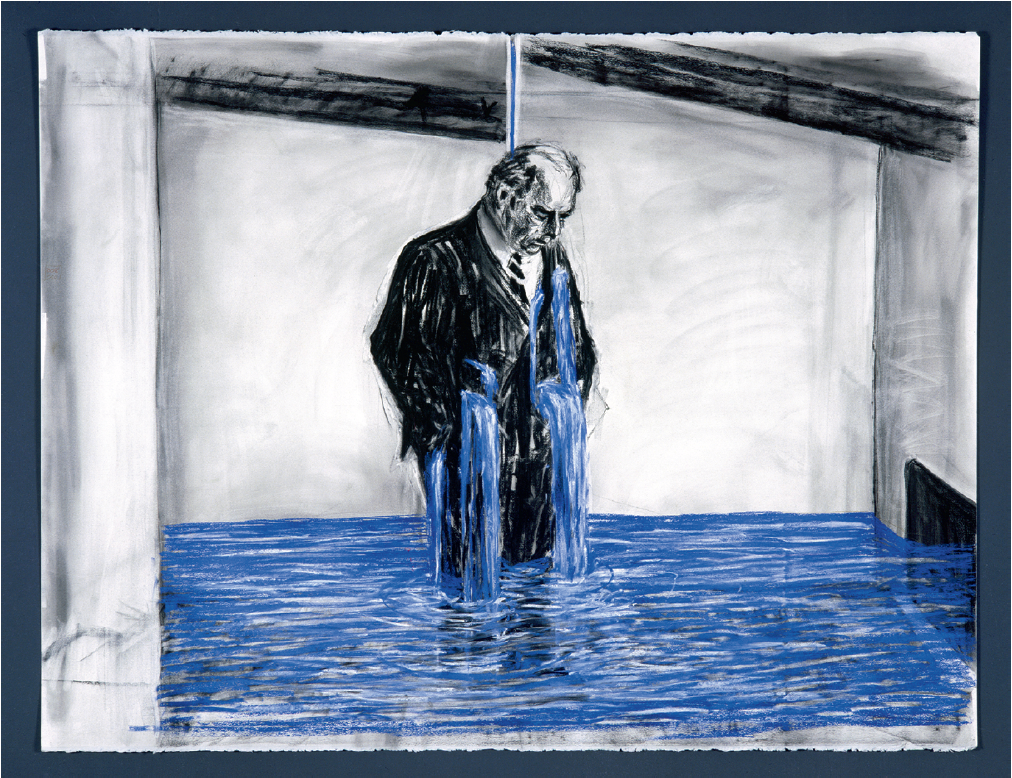

William Kentridge, drawing for the film Stereoscope, 1998–99, charcoal, pastel, and coloured pencil on paper, 47 1/4 x 63”. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2008 William Kentridge. Photo courtesy the artist and the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Another Modernist absurdity: poor Gogol’s errant nose. Here is a proboscis that achieves great political status while it’s owner looks on powerless and persecuted by his own body part. This turn of events is explored in a suite of films in the gallery dedicated to the artist’s preparations for staging Shostakovich’s The Nose. (The opera will be performed at the Met in New York in 2010.) On three of the four gallery walls, the multi-channel projection I am not me, the horse is not mine, 2008, explores Russian Constructivism, the artist’s resolution of the movements for his animated nose, and sections of the frighteningly preposterous interrogation of Bukharin by Molotov during the 1936 Plenum of the Central Committee. On the fourth wall is a film that blends animation and archival footage to show the Nose, a drawing, riding horseback at the front of a Stalinist parade.

Situated chronologically between these two pursuits are two of Kentridge’s own inventtions—semi-potent potentates such as Soho Eckstein and Felix Teitelbaum, melancholy and beleaguered Jewish businessmen who star in a series of Kentridge masterpieces. In one of the most memorable of the drawn films Stereoscope, 1998–99, Felix weeps until his suit pockets fill to overflowing and flood the room with tears. Soho works the telephone lines that connect him to the economic pulse of the country. When long suppressed violence erupts, these lines turn into vectors for attack, until a feral black cat curls himself up into a bomb and explodes. Soho and Felix are anachronisms whose time is up.

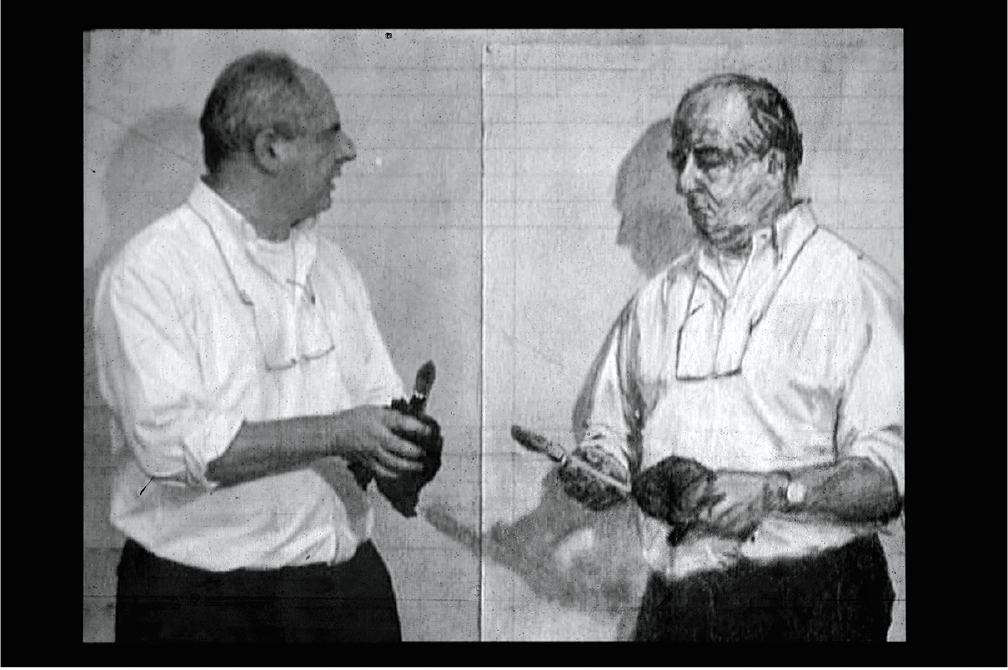

The other two themes explored in the exhibition address the artist’s process and the mechanics and mysteries of filmmaking and theatrical invention. The films, drawings and prints gathered in a section called “Parcours d’Atelier: Artist in the Studio” date from 1979 to 2003 and allow a glimpse behind the wizard’s curtain at the man making the marks on the page. The multi-channel 7 Fragments for George Méliès, 2003, pays homage to the inventive French cinémagician while showing off Kentridge’s own inventiveness. In one film fragment, the artist climbs a ladder that is leaning against the wall of his studio; when he disappears from the top of the frame, a drawing of the ladder crashes to the ground. In another film, he draws and tears and mends his own life-sized self-portrait. Kentridge also recreates Méliès’s 1902 film Le voyage dans la lune, transforming a demitasse cup into a telescope and an espresso pot into a rocket ship that blasts into outer space. While the artist’s imagination soars, Kentridge, over whose shoulder we watch this ambitious voyage, remains hidebound in his studio.

William Kentridge, Invisible Mending (still), from 7 Fragments for Georges Méliès, 2003, 35mm and 16mm animated film transferred to video, 1:20 min. Collection of the artist, courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg. © 2008 William Kentridge. Photo: John Hodgkiss, courtesy the artist.

In another darkened gallery, Kentridge brings his cinematic inventiveness to the 2005 staging of The Magic Flute for La Monnaie opera in Belgium. In one animated work, Learning the Flute, 2003, which projects white chalk drawings on a blackboard, Kentridge develops his visual language for the production. By inverting the usual positive-negative relationship of black marks on a white page, he expresses the triumph of Sarastro, the priest of the sun, over the Queen of Darkness. In Preparing the Flute, 2005—a miniature theatre with hand-drawn curtains and architectural details— Kentridge intermingles the imagery developed in these “negative” drawings with sequences of largely abstract sightlines and fireworks as he works through the musicality and theatricality of the opera. In a third piece, Black Box/Chambre Noir, 2005, a complex mechanized miniature theatre with moving parts and moving images, Kentridge departs from the literal text of The Magic Flute to explore what he refers to as the opera’s “toxic mixture” of concentrating “all knowledge with all power.” This narrative is pure Kentridge: German colonial entitlement taken to the extreme of genocidal savagery in the early 20th-century slaughter of the Herero people. The rhinoceros that appears in both Kentridge’s production of The Magic Flute and Black Box morphs from a drawing to archival footage, and from the savage beast tamed by Mozart’s delightful score to a victim in a hunter’s scope.

Concurrent to the exhibition at SFMOMA, Pacific Operaworks mounted Kentridge’s production of Monteverdi’s The Return of Ulysses that the artist staged in collaboration with the Handspring Puppet Company of Cape Town, South Africa, a group with whom the artist collaborates frequently. Kentridge updated the tale, recounted as a flashback while Ulysses is on his deathbed, to a hospital in 20th-century Johannesburg. Singers stand side by side with puppeteers operating life-sized puppets enacting the saga of Ulysses’s circuitous route home to his faithful wife, Penelope, who has deflected all suitors during her spouse’s 20-year absence. Kentridge’s hand-drawn animation sets the stage, and the old man’s ailing heart—drawn in both anatomical and mechanical form—hovers over the scene, symbolizing the bonds of love and the frailty of the flesh. His puppet form makes his journey home through an animated allée of tall trees, winding up not at an ancient domicile but at a modernist house, as if his journey has taken him so long to complete that he has travelled from antiquity to the present day. The story’s timelessness allows the narrative to be viewed from an updated perspective when ancient codes of honor are no longer in force. The homecoming of this supposedly great, archetypal hero can be seen as being heartlessly consummated in senseless slaughter. Once more, there are no heroes, just victims. At least Kentridge has Méliès. ❚

“William Kentridge: Five Themes” was exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art from March 14 to May 31, 2009. The exhibition will travel to Fort Worth, West Palm Beach, New York, Paris, Vienna, Jerusalem and Amsterdam in 2009–2011.

Susan Emerling is a writer living in Los Angeles.