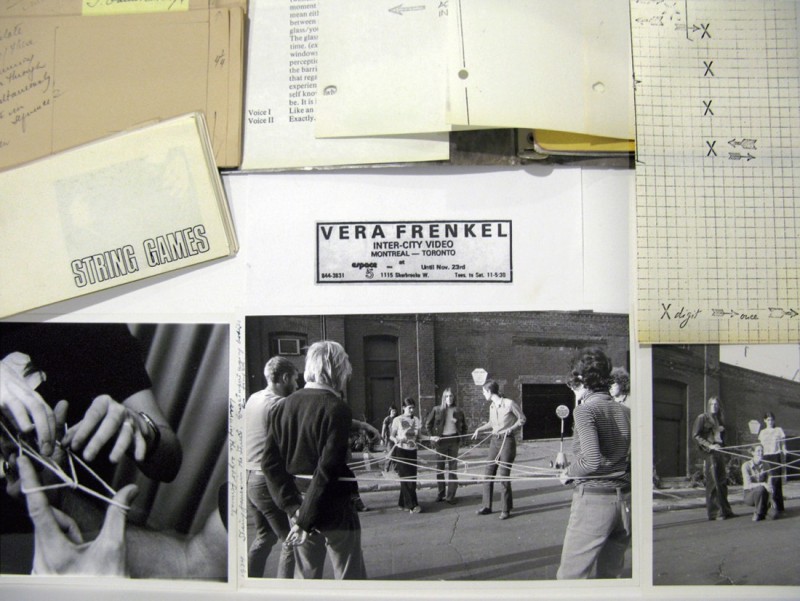

Vera Frenkel

Protean Sites and Sightings

I was thinking about insincerity and here I am sincere. —Lyn Hejinian, My Life, Green Integer, 2002.

There is so much here, it’s almost daunting. I have the Vera Frenkel monograph from German art book publisher Hatje Cantz (2013) before me on my desk, as well as a flotilla of adjacent catalogues, articles, DVDS and beckoning websites, all spiralling forward to a fuller and fuller understanding of Frenkel’s work. This is, of course, a never-ending ambition, simultaneously provoked, galvanized and fueled by the artist’s mercurial recourse to the centripetal fragment, to the floating, modulating, redressing archive, to the frequently reworked multimedia construction of what she has so aptly called “a home for uncertainty.”

Vera Frenkel, The Blue Train, 2012, multi-channel photo-video-web installation; video still from left-hand monitor of main diptych. All images and photographs: courtesy the artist.

It is surely true that, as Lyn Hejinian puts it in her My Life, “A fragment is not a fraction but a whole piece.” And when we visit or tour a Vera Frenkel installation—invariably a fraction of a fragment of a necessarily irresolute resolution—in one or other of its evolving manifestations, we may well feel that we have somehow seen the piece, diligently witnessed it and sufficiently understood it.

But Frenkel’s work is protean, growing ever more reflexively intense as it rolls along. It is densely palimpsestic. It trades so searchingly in the chthonic excavation and analysis of hitherto darkened grottos of cultural memory, it requires of the viewer not so much a visit as a kind of extended apprenticeship, a willing, open-hearted dedication to its proliferating researches, discoveries and kaleidoscopic presentations.

The Blue Train, 2012, video still from drawn animation sequence, left-hand monitor of main diptych.

“We live in metaphor,” Frenkel has often noted. I’m certain we do. We also live in the partialist realms of metonymy and synecdoche—this last having been identified by Kenneth Burke in his A Grammar of Motives (Prentice Hall, 1945), as being “… part of the whole, whole for the part, container for the contained…material for the thing made…cause for the effect, effect for the cause, genus for the species, species for the genus….” Frenkel has said that for her, art is “an instrument of questioning rather than a seeker or provider of answers or even spiritual healing.” We never see anything with perfect finality, in perfect wholeness.

Body Missing, 1995, multi-channel photo-video-text installation and website (www.yorku.ca/BodyMissing); photomural, Station 4, 2000.

So it is with Frenkel’s work and so it is with this new book about it. As rich and teeming as the book is, it cannot possibly deliver her entire into your waiting sensibility. At best, as “part of the whole, whole for the part, container for the contained,…” the volume is a variable sounding chord of witnessing, revisitation, recollection, surmise and revelation. Though structured chronologically, the book is essentially circular in the sense that it can be used both as the beginning of Vera Frenkel Studies and as a coda to them, the story being—as Frenkel has frequently pointed out—always unfinished.

To read the rest of Gary Michael Dault’s article on Vera Frenkel, please order Issue #130 here.