“Van Doesburg and the International Avant-Garde: Constructing a New World”

Like great minds, great museums sometimes think alike. The Stedelijk Museum De Lakenhal, a small municipal institution in Leiden, The Netherlands, was preparing a major exhibition of the work of Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931), instigator of the Dutch Modernist movement De Stijl, when curators at the Tate Modern came up with the same idea. From this coincidence sprang the unusual cooperation between Leiden’s modest museum and the giant Tate, resulting in the largest presentation ever for the Lakenhal. After it closed in Leiden, the exhibition opened in February 2010 at the Tate Modern as part of its sequence of exhibitions on early Modernism. A catalogue published on behalf of both venues was edited by the Lakenhal’s curator Doris Wintgens Hötte and the independent curator and art historian Gladys Fabre.

Van Doesburg lived in Leiden from 1916 to 1921, the year he left for Weimar. In 1917, he initiated De Stijl magazine together with other Dutch Modernists such as the architects J J P Oud and Gerrit Rietveld, and artists Piet Mondrian, Bart van der Leck and the Hungarian-born Vilmos Huszár. The monthly publication became a forum in which the artists, reacting to the horrors of the First World War, debated utopian ideas of recreating the world through art. De Stijl proposed that artists all over the world “work for the formation of an international unity in Life, Art and Culture.”

In large part, De Stijl gained its art-historical fame from Mondrian, but the current exhibition draws van Doesburg out of Mondrian’s shadow and highlights his unique contributions to the ideas of the movement. Van Doesburg gave shape to De Stijl’s ideas in his own multidisciplinary practice and analyzed the work of others in countless texts. Work of many of the artists that he came in contact with—El Lissitzky, László Moholy-Nagy, Kurt Schwitters, Hans and Sophie Arp, Raoul Hausmann and Alexander Archipenko among them—testify to van Doesburg’s influence on the international avant-garde. Photographs and reports of meetings, congresses and parties in various European countries show him to be a tireless promoter of De Stijl’s ideas, but also a provocateur who exploited the contradictions in Modernist movements, instigating heated debates.

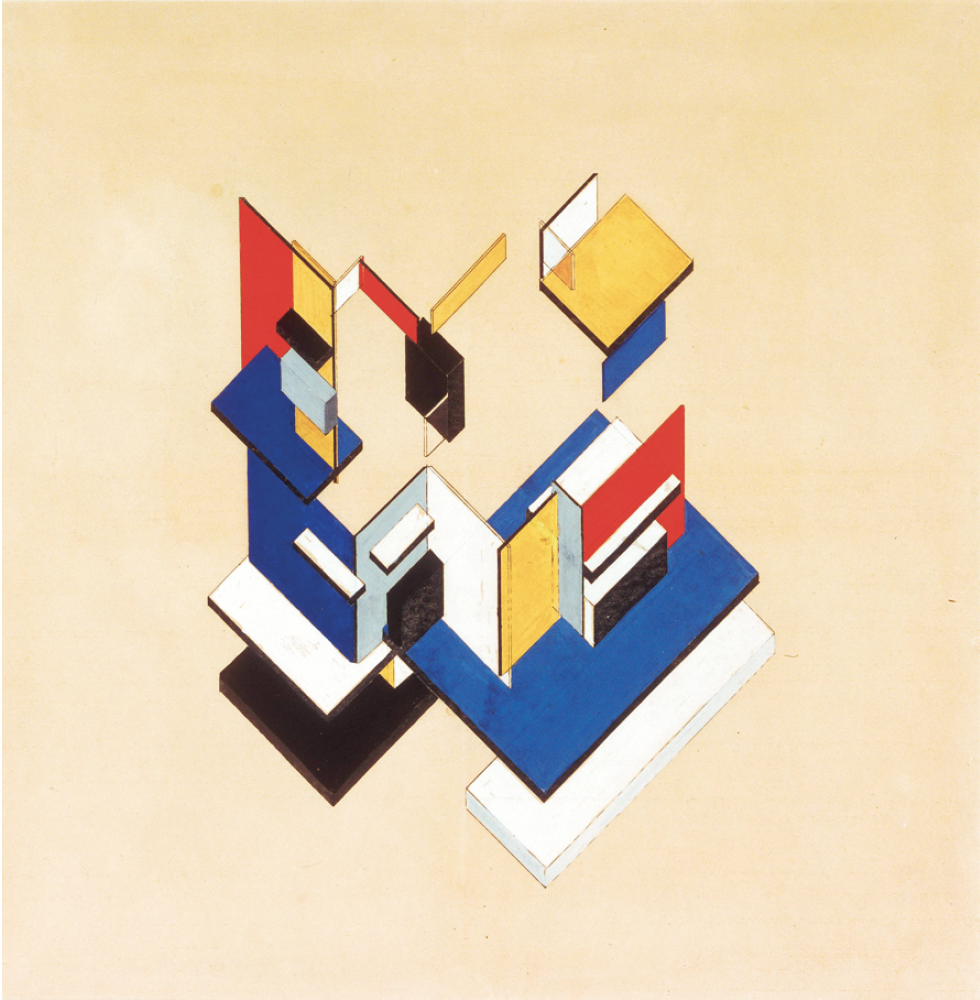

Theo van Doesburg, Counter-Construction, Axonometric, Private House, 1923, gouache on lithograph, 572 x 572 mm. Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., 1947. Photographs courtesy Tate Modern, London.

Influenced at first by Kandinsky and later by Mondrian, van Doesburg adhered to a Modernist essentialism that searched for an elemental, universal style built from geometric forms. What set him apart from Mondrian, and led to a final break-up in 1926, was van Doesburg’s belief in a dynamic principle that could be applied equally to painting, architecture, sculpture, design and typography. He disagreed with Mondrian’s narrow focus on painting as a singular and static form of art. In 1926 he introduced diagonals in his paintings, creating a dynamism that broke with Mondrian’s horizontals and verticals and meant the end of a friendship.

Not surprisingly, van Doesburg found The Netherlands too small for his ambitious intention to renew all art forms, and in 1921 he left Leiden for Weimar, Germany, with Nelly van Moorsel, his third wife. In a lecture at the Bauhaus, he advocated De Stijl’s radical abstraction, which ran counter to the value of individual craftsmanship and Johannes Itten’s mystical expressionism that still reigned at the school. At the Bauhaus, van Doesburg’s ideas on abstraction were considered too dogmatic. He failed to receive an appointment at the school and began teaching from his own studio nearby. As is clear from works in the exhibition by Karl Peter Röhl and Max Burchartz, who were his disciples at the time, his lectures had an undeniable influence on Bauhaus students.

Once he had moved from The Netherlands, van Doesburg regularly made missionary expeditions to Germany, Belgium, Italy, Spain and France, where he settled in 1923. Through lectures and conferences, through meetings with Modernist groups and individuals—whether like-minded or opposed to the De Stijl’s premises—he spread the word that universal geometric abstraction would unite not only disparate artistic disciplines but also eventually art and life itself. He was a tireless networker, convinced that his new world could only materialize if continental, and eventually global, connections and contacts were established and maintained. Thriving on controversy and polemics, he often instigated conflict, as when he organized a Congress of Constructivists and Dadaists in Weimar in 1922 in which Tristan Tzara and Hans Arp participated.

Theo van Doesburg, Simultaneous Counter-Composition, 1929–30, oil on canvas, 501 x 498 mm. Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection, 1967 © MOMA.

Van Doesburg’s dogmatic insistence on geometrical abstraction was contradicted in his own personality by his enthusiastic, if sometimes covert, participation in the Dadaist movement. He created assemblages and collages and, under the pseudonym I K Bonset, published a Dadaist magazine Mécano (1922-23), for which he wrote Dada poems and manifestos. In 1923 he organized a Dadaist tour of the Low Countries with his friend Kurt Schwitters and Vilmos Huszár.

The exhibition makes it clear that van Doesburg did not suffer the isolation of a studio practice for any length of time; his own work—collages, writing, painting and, in particular, his architectural designs and collaborations—are well represented. His house in Meudon near Paris—finished only a year before his death in 1931—was the only building that went beyond the design stage. Van Doesburg’s architectural projects, including his models and the interior designs of the Café Aubette in Strasbourg, come closest to materializing his essential ideas of dynamism in geometric abstraction and the fusion of artistic disciplines.

Van Doesburg’s relevance may lie in his attempts to embody in his own life and work two contradictory premises of Modernism—essence and contiguity. Undermining the Constructivist principle of Modernism with Dadaist destruction, and the static elements of vertical and horizontal lines with the dynamic diagonal, van Doesburg proved, perhaps unwittingly, that essence of form may be desired but remains elusive, always waylaid by the contiguity of life. ❚

“Van Doesburg and the International Avant-Garde: Constructing a New World” was exhibited at the Stedelijk Museum De Lakenhal in Leiden from October 20, 2009, to January 3, 2010, and at the Tate Modern in London from February 4 to May 16, 2010.

Petra Halkes is a painter, art writer and curator living in Ottawa.