“Up North”

The two words “Up North” call up the act of going somewhere or being somewhere, in another space, one that is both real and unreal, imagined as different from here (wherever that is), as if it were on the edge of the map of familiar reality.

Where is it, exactly? “Up North” is directional, but ambiguous. Its location shifts. It is relative to where you are. It is a concept, a white screen for projections, a vast region of the mind. Yes, it usually has something to do with wilderness, extreme cold and snow, and the notion of last frontiers and new beginnings. It speaks of natural splendours, purity, a place to escape to. It is reflected, shaped and reshaped by art, literature, film, music, theatre and popular culture. A last bastion of the sublime comes into it, too.

As the title of the exhibition curated by Catherine Crowston at the Art Gallery of Alberta, “Up North” also rings with the self-consciousness of knowing that while North has regions still to be explored, other artists and writers have been there before. Most often, the idea of North, so central to the formation of Canadian identity, is represented in exhibitions by historical works. Crowston enlarges and complicates the idea of North by showing recent work by contemporary artists, with different ideas of North, from three circumpolar countries.

Two of the artists, Jacob Dahl Jürgensen and Simon Dybbroe Møller, who collaborated on an event, installation and recording, are Danish; Kevin Schmidt is a Canadian from Vancouver; and Ragnar Kjartansson and David Thor Jonsson (who collaborated with Kjartansson in the video The End) are Icelanders, whose home is Reykjavík. It should be remembered, though, that where artists come from does not determine where they live, work and show: Jürgensen lives in London, Møller in Berlin. All of these artists show internationally. Their global outlook, it would seem, cannot help but affect their particular ideas of North and the way they intersect with ideas about the homogenization and commodification of culture by global capitalism.

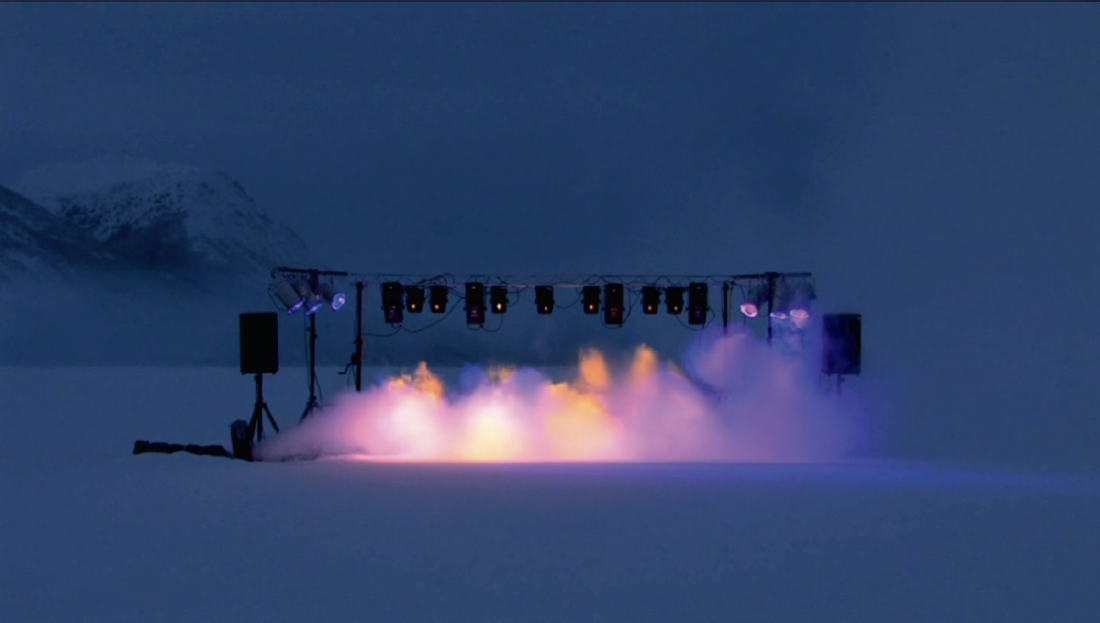

Kevin Schmidt, Wild Signals, 2007. HD video, 9 minutes, 42 seconds. Courtesy Catriona Jeffries Gallery, Vancouver and the Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton.

Schmidt travels to the Canadian Arctic, where the Northwest Passage, unsuccessfully sought for centuries by explorers looking to gain economic and geopolitical advantage for their many countries, has thawed and opened in the past few years. He explores this “empty” space as potential of a different kind. The Danes, who say Denmark has no wilderness, go south to find a volcanic island in the Mediterranean and stay for a utopian idyll, collecting flotsam and jetsam with which to make musical instruments. Kjartansson and Jonsson play out a parodic fantasy of dandified, singing mountain men in the snow-covered Canadian Rockies at Banff, Alberta, which Kjartansson has likened to a Disney setting.

The artists have in common their undertaking a journey to make their work, doing performances that involve music they have composed, making music and video or film the sole or central elements of installations, and representing the wilderness as a stage for action or embodied fictions. Points of similarity converge in the works at the same time that differences separate them, creating an engaging counterpoint in the polyphonic dialogues they strike among themselves. The two brilliant works in this show are Schmidt’s Wild Signals, 2007, and Kjartansson’s The End, 2009, but all of it is good.

Flotsam and Jetsam, 2010, as the Danes’ work is called, reads almost like a myth of origins played out on the hardened lava flows of Pantelleria, an ancient island near Sicily, with evidence of habitation 35,000 years ago. In reality, the island is neither unpopulated nor a desert. Jürgensen and Møller stayed for six weeks with seven friends in the home of an Italian art collector. Together they scavenged for debris cast up by the sea—driftwood, bottles, pieces of contemporary chrome furniture, glass jars, cans, metal pipes, tile fragments—and fashioned it into rudimentary musical instruments, which could be played by plucking strings, striking surfaces or blowing across the top of empty volumes like bottles and jars.

An island recording of the strangely harmonious improvised music plays in the installation, which evokes a museum gallery in which the instruments change function to become, simultaneously, artifacts and found-object sculpture. A film projected on the wall documents the ritualistic actions of their self-sufficient colony. Time seems to collapse and conflate contemporary, modern and ancient historical periods, as if this were an allegory of beginnings. The wilderness that frames these human endeavours lies in the vastness of the sea more than on the island to which the Romans once sent important people and royals in exile. The installation, which frames the island idyll, turns the artists into poetic ethnologists.

Jacob Dahl Jürgensen and Simon Dybbroe Møller, Flotsam and Jetsam, 2009 (-2011), video colour, sound, found objects, vinyl record (24:03 min.), 13 minutes, 44 seconds. Installation dimensions varies. Courtesy the Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton.

The myth of wilderness as timeless and unchanging also underlies Schmidt’s A Sign in the Northwest Passage, 2010, and Kjartansson’s five-channel video, The End, 2009, in which the artist and his sidekick Jonsson are freezing, increasingly besotted Europeans dressing Western in their fur caps, and drinking spirits to keep warm. On each of the installation’s five screens, the two appear in front of a different Banff beauty spot, playing various instruments and humming or singing a folk-country song. The ensemble forms a nine-man band that encircles the viewer. Unlike the nine musicians in Flotsam and Jetsam, the multiplied Icelanders are an anarchic bunch whose music descends into cacophony, mixing up the simple folk-country theme with chords of high Romantic piano concerti, blues, rock and a little Stockhausen. Just when you think the song is coming to an end, it begins again in a 30-minute cycle of deferrals. “I am in Hell, you are in Heaven,” sing the artist/musicians, as if trapped in a frontier myth they are doomed endlessly to repeat. The music, composed by Jonsson, tells its own story of things falling apart. Schmidt’s song for his visually stunning, colour-saturated Wild Signals, which also plays off the music-video form, has a narrative function as well. Set in the middle of a frozen lake in Arctic twilight, the piece is a son et lumière that the unseen artist performs on a small synthesizer in the snow. It “plays” on a proscenium-like apparatus made of light stands, an overhead bar of spotlights and speakers. The famous five-tone motif from Close Encounters of the Third Kind, 1977, sounds hesitantly as the coloured lights come up, at first flashing like lightning. Then the lights begin to dance and the music grows confident as John Williams’s tonal signal, in the film a mathematical language scientists devise to communicate with aliens, acquires an infectious drumbeat and turns into a rock song.

Wild Signals, an inversion of the Northern Lights, suggests that we deal with the silent unknown by projecting onto it our own desires and taming cultural codes. Not silent, not unknown and not empty, certainly to the peoples who live there, the Arctic is instead being colonized and exploited by corporations interested in its natural resources. Schmidt’s A Sign in the Northwest Passage, a rustic billboard left on the Beaufort Sea north of Tuktoyaktuk, issued a warning in the apocalyptic text taken from Revelations that he hand-routed into its wooden boards: plague, pestilence and disasters visit the land, men die in agony and merchants weep. When the ice broke up in the springtime, the sign, built with wooden kegs on the base, would float away. The sign is present in the installation as a large colour photograph. As a coda to the piece, the AGA sent Schmidt to the Arctic this past summer to look for it. A video shown inside a white tent, evoking an expedition, follows a search by air and sea that can find no trace of it. It is as Schmidt says, “long gone.” Presence and absence is a consistent underlying theme in “Up North”: thinking of there and being here, seeking an experience of the sublime, which is absent in contemporary life, only to find in its place this constant yearning. ❚

“Up North” was exhibited at the Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton, from September 10, 2011, to January 8, 2012.

Nancy Tousley is an art critic, journalist, independent curator and Critic-in-Residence, Alberta College of Art and Design.