Tristram Lansdowne

Tristram Lansdowne’s rigorous and transgressive approach to watercolour painting is categorically unmatched. He creates uncanny images that are at once ambiguous and illusory, highly realistic and unbelievable, and that reflect our current moment of hyper-mediatization. The paintings in “Well Weather Window” were created during a year-long residency at the Roswell Artist-in-Residence Foundation in New Mexico. They are the third in a larger series of works composed almost entirely using trompe l’oeil and successive internal framing strategies. While continuing to reference canonical uses of artificial space from within art history—the murals of Pompeii, Jan van Eyck’s altarpieces, de Chirico’s abandoned cities—as well as contemporary sources like computer desktop design and architectural advertising, in “Well Weather Window,” Lansdowne also incorporates his own experience of living in the peculiar and sublime climate of the High Plains.

Throughout art history, painters have used techniques like vanishing points, horizon lines and lighting to simulate the depth perceived when looking through a window. In a desktop metaphor, drop shadows, shading and heavy borders are also used to create a space that mimics a user’s physical desk, where documents, folders and files are arranged. Lansdowne exploits these systems of illusion in his paintings by using orthogonals and atmosphere to create depth, as well as a process of “windowing” where multiple, resizable square or rectangular units of display overlap one another. Frames, insets and porticoes overlie and interrupt one another continuously within these works, as threshold upon threshold intersects in a series of disparate juxtapositions.

Tristram Lansdowne, installation view, “Well Weather Window,” 2025, Galerie Nicolas Robert, Toronto. All images are courtesy Galerie Nicolas Robert. All are watercolour on paper. Left to right: Gag, 2024, 76.2 × 62.2 cm; Slough II, 2024, 76.2 × 62.2 cm; Supply Line Shrine, 2025, 83.8 × 86.4 cm; Bad Faith Hospitality, 2025, 107 × 84 cm; Cormorant, 2025, 70.5 × 81.3 cm; Naturalizer, 2024, 127 × 111.8 cm.

In Cormorant, four distinct image layers frame one another successively, shuttling us from an interior to an exterior, to a surface, to an architectural setting: a nondescript beige lobby, a hazy empty beach with faded canvas umbrella, a close-up of a black plastic bag, and a hallway of infinitely receding pistachio-tinted arched doorways with a complex of lavender shadows. Here, a sequence of textural rhythms and associations bounce off one another in visual conversation—the blandness of the outer frame ties to the flatness of the arched passage at the centre of the image, while the shimmery shoreline and shiny plastic reflect one another’s gleam. They connect formally but resist metaphorical interpretation. Instead, their combination echoes a series of open tabs, a trail of hyperlinked Web pages, or an algorithmic feed generating content based on the viewer’s most recent search history.

Many of the works in this show convey an arid stillness derived directly from the desert city where they were made. Where Slough II portrays an abandoned storage yard under the light of the full moon, Lover’s cover depicts a sunburnt grassland, hazy in the midday sun. Both works are emblematic of Lansdowne’s windowing effect— each are layered with insets that contain discordant objects—three empty wigs in the latter, and a slime green skull and snake in the former—and are bordered by faux three-dimensional boxes containing foodstuffs like a 3 Musketeers wrapper or chocolate-dipped strawberries. Human activity is implied here but never pictured directly. It is this absence that produces apprehension.

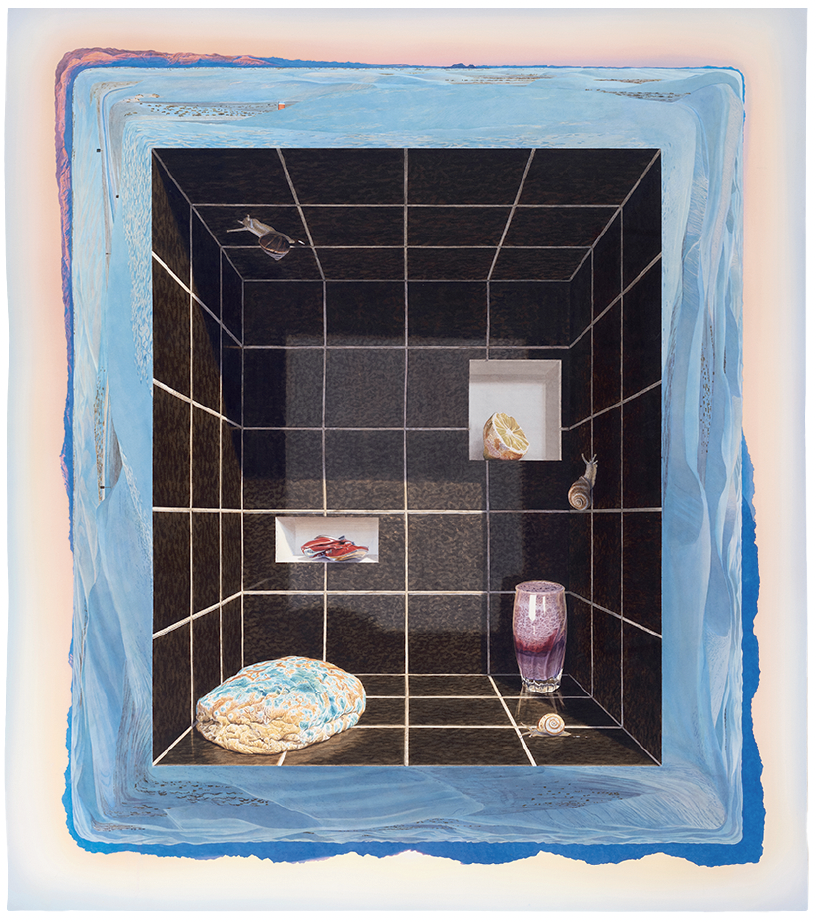

Tristram Lansdowne, Naturalizer, 2024, watercolour on paper, 127 × 111.8 centimetres. Image courtesy Galerie Nicolas Robert, Toronto.

Disquiet breeds further in Naturalizer, where a shower stall clad in a vortex of black tile is inhabited by a trio of snails, slithering languidly across the slick ceramic surface. A frothy blueberry smoothie rests temptingly in one corner of the stall, while, in the other, a flaccid loaf of bread slumps, deflated under the weight of topaz-coloured mould spores that cover its softened crust. Cubicles that should hold soap and shampoo are instead occupied by a dehydrated flank steak and a shrivelled lemon, cut open to reveal its parched pulp and leathered, decaying skin. Lacking plumbing, this dry interior mirrors the parched desert landscape that wraps around it. Acting as this painting’s border, the interior captures the sand and sky at sunset in an ethereal wash that fades from the palest pink to vibrant cerulean. The contrast between the softness of the exterior frame and the rigid grid of the interior, coupled with their competing spatial expansions and compressions, creates a further dissonance within the work, a strangeness that draws you into the absolute inertia of the painting. Whose, or what’s, world do we have a window into here?

Lansdowne’s works capture what it is to live in an increasingly image-saturated culture, one where the struggle to create coherent meaning slides further and further away with every minute spent doomscrolling. Emblematic of an international generational shift, the paintings in “Well Weather Window” reflect the experience of both perceiving and participating in a world that is nearly fully digitized. They act as proxies for our larger anxieties over the role illusion and veracity can continue to play. Lansdowne’s brilliance is in the way he responds to these existential concerns, pushing the structural foundations of representational image making, drawing deeply from both contemporary mass culture and art history, and suggesting that painting may still be an antidote.

“Well Weather Window” was exhibited at the Galerie Nicolas Robert, Toronto, from May 3, 2025, to June 7, 2025.

Rhiannon Vogl (she/her) is a PhD candidate in art history at the University of Toronto. Previously, she was an associate curator in the Department of Contemporary Art at the National Gallery of Canada.