Tricia Middleton

It might behoove us to start right in the middle: When thinking and intuition become fossils, you know things are going slightly awry.

This mordant barb is but one of several dozen that appear in “The Call is Coming from Inside the House,” the latest outing by Montreal artist Tricia Middleton. It is neither the most telling dictum to appear in the show, nor the most caustic, though its arrival two-thirds of the way through the 50 hand-painted sign-texts that anchor the exhibition offers a lucid moment of pause in Middleton’s project, which is otherwise masterfully, if not pathologically, beguiling.

Tricia Middleton installation view of “The Call is Coming from Inside the House,” 2011, at Mercer Union. Photograph: Tricia Middleton. Images courtesy the artist and Mercer Union, Toronto.

A makeshift workspace provides the primary scene for the show—a studio that both time and its inhabitant have forgotten, we quickly sense. Traces of a disappeared character hang heavily in the air: a pair of wax-encrusted shoes lie frozen in front of a sofa, underneath which a large number of books, primarily philosophical and psychological in nature, have been shoehorned, along with coffee cups, empty booze bottles and a blanket. Alongside the sofa sits a desk amassed with paint (for the aforementioned signs), hand-written pages (both perfunctory and expulsive) and other workaday materials that look freshly, frantically rifled through. Above the desk is a curious selection of objects—snapshots, tchotchkes, notes to self. A piece of paper taped to the wall begs: Serious question: how should one spend their time here on earth if really given a choice? Underneath it sits another that reads: Die.

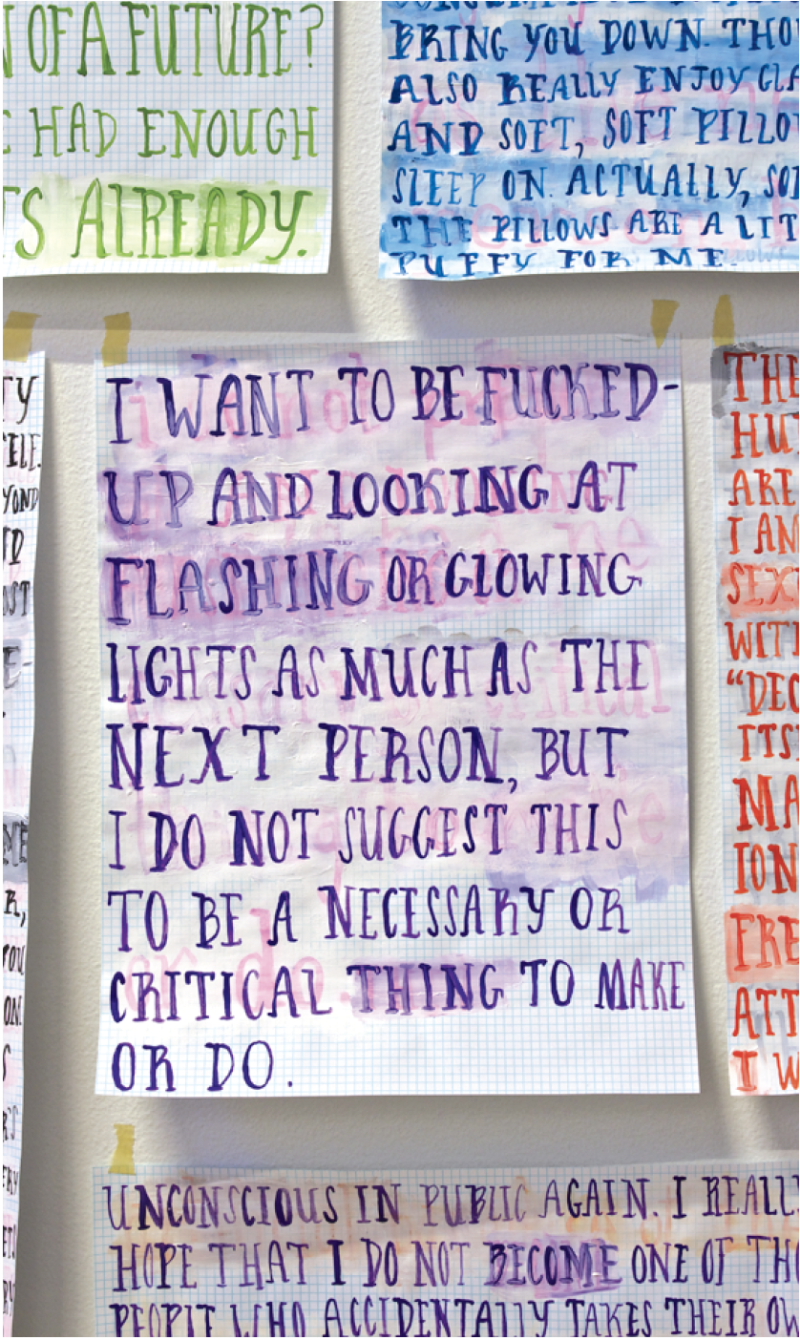

Directly opposite, an entire wall is adorned with signs, each composed in watercolour on graph paper in a uniform serif type. These texts perambulate through broad, fraught territory: quotes (and misquotes) from thinkers such as Breton, Debord and Engels; comments and complaints about topics ranging from labour politics to art world bluster to the relevance of judgment; and a healthy dose of biting personal observation on aesthetics and social existence. Case in point: I want to be fucked up and looking at flashing or glowing lights as much as the next person, but I do not suggest this to be a necessary or critical thing to do. The texts are, by turns, polemical, acerbic and pathetic; the responses, however, are cacophonous and dispiritingly incoherent.

What emerges is a portrait of deterioration—of language, of ideas, of self. The scene has been structured carefully around a set of uncanny anachronisms. Nineteenth- century typography is used to render Internet-speak, and that lends it temporal heft, a suggestion that the ontological struggle before us extends outwards in all directions from the moment of encounter. We are confronting the vestiges of a decline, to be sure, though allusions to escape and death, of which there are plenty here, are weighted not with reference to expiration or calcification, but rather to a Nietzschean metamorphosis, a constant state of transformation, of entropy.

Tricia Middleton installation view of “The Call is Coming from Inside the House,” 2011, at Mercer Union. Photographs: Jon Sasaki. 50147txt.

Middleton bears this out for us in details large and small. The signs, for example, are hung unapologet- ically with painter’s tape to signal their availability for continuous, anxious rearrangement. So, too, do the texts themselves evince traces of mutation, both in their willful contradiction of one another and in the cloudy layers of paint that divulge a compulsive sharpening, familiar to anyone who has spent time wrangling ideas: It could be worse, reads a note in the space, I could be writing reviews for a living.

This transfiguration, however, is perhaps established most shrewdly in the exhibition’s secondary scene, which unfolds behind a curtain of vintage bedsheets strung across the far end of the studio. Beyond it, one encounters four mountainous forms bathed in blue light. These are preternatural, almost talismanic sculptures. Close inspection reveals they are composed from refuse—runoff, as Middleton describes it: dust, studio debris, bits of fabric, cotton balls, coffee cups and other remnants of everyday life, all fashioned in a palette of pinks and blues with Middleton’s signature combination of candle wax, glitter and paint. These are precar- ious, suggestive objects, captivating in both form and content. They seem prone to collapse at any moment but hold upright as though by centripetal force alone. Much like the psychic overflow of the studio they abut, they are junky, but compelling—alive with the hand of their maker, even if of questionable structure.

It would be simple for these scenes to function on archival or vestigial terms; they could well serve as artifacts of this particularly paltry moment in late capitalism, though Middleton coaxes as readily forward as she does back. Indeed, these works seem to suggest that, while the material and intellectual resources of contemporary life are increasingly transient, the time has not yet come for us to treat them as dead and stripped of the charge of psychic engagement. ❚

“The Call is Coming from Inside the House” was exhibited at Mercer Union, Toronto, from November 11 to December 10, 2011.

Matthew Hyland is the director of Oakville Galleries.