Tracy Peters

Winnipeg-based photographer Tracy Peters’s show “SHED Unusual Migration,” at AceArt, is a deep engagement and exploration of place. Over the last three years, Peters has painstakingly photographed a small agricultural storage shed on a semi-rural property located in Winnipeg’s outskirts. Recording the changing seasons, the vagaries of weather, the encroachment of foxtails and other wild grass, the nesting of birds, Peters documented a site caught in interstitial time between an agricultural past and the encroachment of suburban development. Eschewing nostalgic tropes of rural loss, populated by the iconography of rusting tractors, Peters brings an enormously sophisticated perspective that asks us to look closely at the shed, to return and look again, to cast our eyes to the edges and corners, to focus on the minute details and their changes, even as she radically rethinks landscape.

The exhibition is ultimately a highly mediated work of art, one where technological manipulations of visual representation are ever present but nonetheless done with the most delicate restraint. This under-determined set of photographs, video and sound recordings, and sculptural elements all play with the very materials of the photographs of the shed, using them to build structural components within the installation, even as these photographs depict the shed itself. Peters provides a subtle immanent critique of modernist impatience for the new, that presumptive desire to be shocked and awed, to see change happen with speed, and then to move on in a relentless search for the novel. She reminds us to stop, listen and look, not once, but many times, to see the power of nuance, whether it is in the small changes in the light and wind, or the dynamic qualities of flora and fauna, as they shape and impact a small, seemingly empty wooden out-building in a field. The shed project requires patience, and the installation at AceArt reflects Peters’s admirable persistence with the project, one that now spans years. It is also a model of under-determined restraint, one which carefully avoids narrow narratives but nonetheless opens up space for engagement, critique and reflective analysis.

Tracy Peters, installation view, “SHED Unusual Migration,” 2014, AceArt, Winnipeg. All photographs: Karen Asher. All images courtesy AceArt, Winnipeg.

The exhibition is dominated by a floating curtain made from long strip photographs of the forest floor near the shed property. Peters had originally woven these photographs into the slats of the shed walls, bending them around the worn wood, and allowing the prints to bleach and weather in the elements. In the installation these photographs of foxtails and decomposing leaves, which had, in effect, become another ephemeral layer of the building’s skin, run along one side of the gallery. Though open, this piece nonetheless divides the exhibition space, creating a boundary between the external spaces of the gallery and the installation itself. Rather than reconstructing the shed walls, creating an ersatz shed with strip photographs, Peters reminds us that this is a work of photography, and photography is not wood. In flattening and stretching out the walls rather then positioning them at four right angles, Peters inserts herself, altering, instead of merely reproducing what she is recording. The wooden slats of the shed are horizontal, while Peters’s photographs are turned 45 degrees, creating vertically hanging images, at once singular and part of a larger work. As such the photographs form a complete image that evokes the shed’s walls and also depicts the dying flora of the forest floor (though one that is not easily seen in its entirety) even as they form a wall itself. In this gap between the material wall and representation of walls, Peters opens space to think and reflect.

Peters’s video of the interior of the shed is one of the most arresting and captivating elements within the show. Projected in an alcove that has the effect of replicating the walls of the shed itself, the still shot nonetheless is filled with movement, accentuated by the sound of the wind blowing hard on the creaking structure. Shot on a sunny day, light seeps through the wooden slats as wind blows Peters’s photographic strips and gently illuminates the darkened space. The growing gusts of wind break the seal on the door, and a wondrous burst of light briefly lazes across the frame of the entrance, before the door settles back into its weathered mounting. The play of light and sound makes you feel like you are watching the prairie breathe.

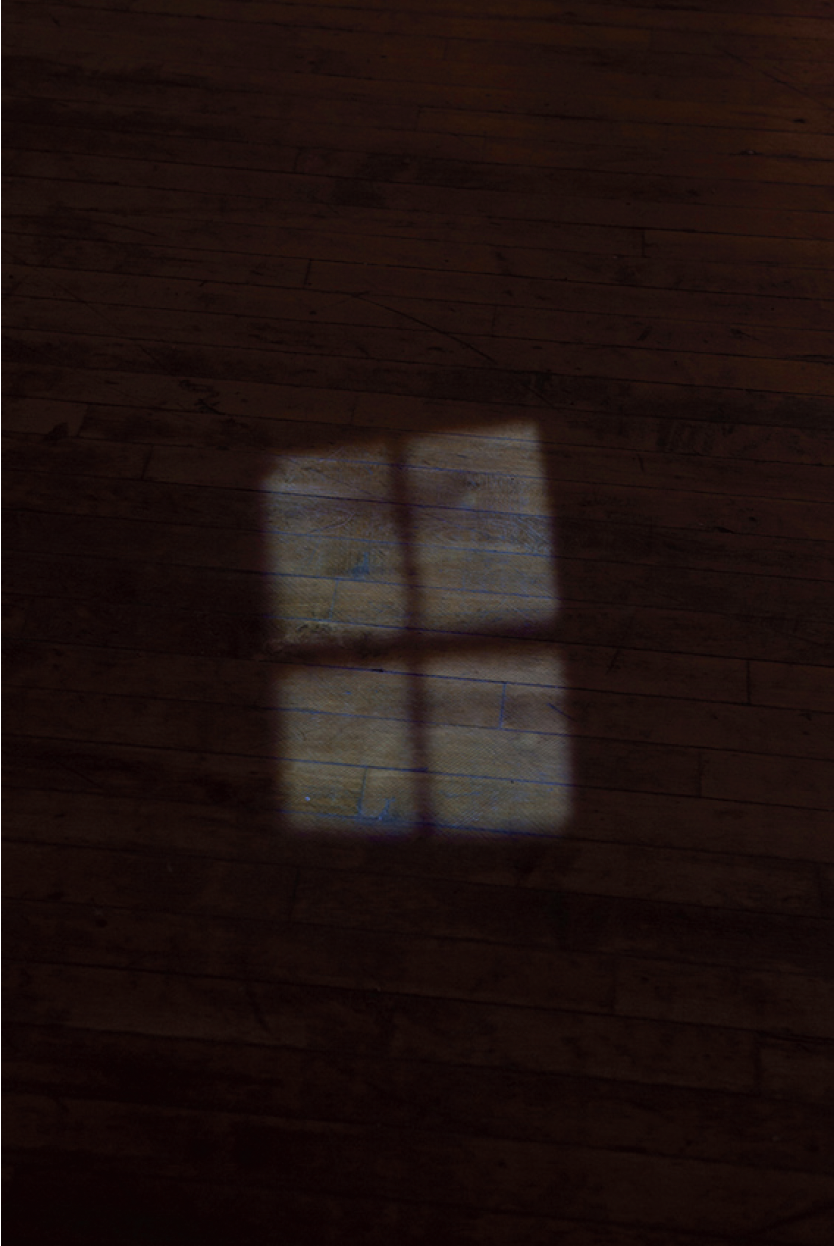

Peters is a master of scale and though some of these elements are impressively larger, she is no less adept working with more intimate traces and details for us to find and delight in. Two such smaller components could be easily missed. The first is a bird’s nest tucked up in the gallery rafters. Easily mistaken for a found natural element the nest is in fact a sculptural object made from very thin photographic strips, again of the foxtails and leaves. The other smaller work is a video projection that is bounced off a small mirror and onto the gallery floor. The video can literally be stepped over, easily unnoticed particularly because it is a projection of light streaming through the shed window onto the shed floor. At moments this sunlight is bright, creating a bisected rectangle on the hardwood of the gallery, but then passing clouds occlude the light and all we see is the gallery floor, there one moment and gone the next. Peters’s use of angles, of capturing the light through the window, rather than the window itself, stresses the need to question representation, to look and think about the relational and the illusiveness of authentic apprehension.

Tracy Peters, Lapse, 2014, video, 30 min., 23 sec., looped.

Here is the hard nose of contemporary modernization in southern Manitoba, one type of development and change that is transforming the region’s landscape. Yet the shed itself is a marker of transformative change and settler colonial modernity. Located on Winnipeg’s western edge in the suburb of Charleswood, the shed is an artifact of the rural agricultural properties that dominated the community prior to the Second World War. Yet these small farms were themselves an imposition on the region. The shed itself is located near a natural ford in the Assiniboine River that was a crucial location in 18th and 19th century buffalo hunt and fur-trade for First Nations and Métis hunters. Indeed, the ford was the key historic site, a natural crossing of the Assiniboine from north to south and an important gathering place in the annual hunts. The agricultural communities that sprung up in this region were themselves part of the displacement of Indigenous cultures and the transition of the Red River from a fur-trade economy into an agricultural economy dominated by settler colonialism. Intentional or not, Peters’s sophisticated and critical approach to the shed opens up space for such historical reflection, in that it demands a focus on change at a deliberate and incremental pace, even as it focuses on human intervention and mediation.

Yet even as the shed is situated in a specific location, the phenomena of agriculture decline, disuse, abandonment and neglect occur as by-products of massive factory farming, and the decline of small mixed agriculture, the very type that was practised on the shed property. Such changes transpire not only at the edges of Winnipeg but are ubiquitous across North America. Ex-urban zones, as writer Mike Davis reminds us, are filled with “track-housing on point,” sprawling ever outward regardless of environmental sustainability. Peters provides us with a hauntingly beautiful meditation on change, one that in its micro attention to native plants such as foxtail understands how environments may be reclaimed, while also reminding us how such ecologies are not fixed end points but can and in all likelihood will be changed once again. Wild prairie grass may be a signifier of the permanence of nature but it is also the marker of the ephemeral and periodic reality of human activity. As the foxtails grew and bloomed around the shed, their presence was also a harbinger of an unseen future transformation, an almost assured fact in the shifting temporality of settled territory. Peters’s “SHED Unusual Migration” illustrates that migrations are not endings, but always protean processes. In thinking about the shed I cannot help but be haunted by the spectre of the bulldozer that will roll over the insurgent flora and rotting buildings and once again transform the site, bringing it into the present time of the latest version of “one great city.” ❚

“SHED Unusual Migration” was exhibited at AceArt, Winnipeg, from September 5 to October 7, 2014.

David S Churchill is a queer cultural critic, sometime curator and Associate Professor of US History at the University of Manitoba.