Total Horizontal Integration

Each in his own way, Guy Maddin, Evan Johnson and Galen Johnson, the partners in Development Ltd., is a dreamer. What they have dreamt up is a movie company that operates out of total vertical integration; they do all their own writing, shooting, editing, compositing and sound and music design. Since they officially joined together in the summer of 2010, Development Ltd. has produced eight projects, including documentary, short and feature films; an ambitious interactive Internet project; and an art installation.

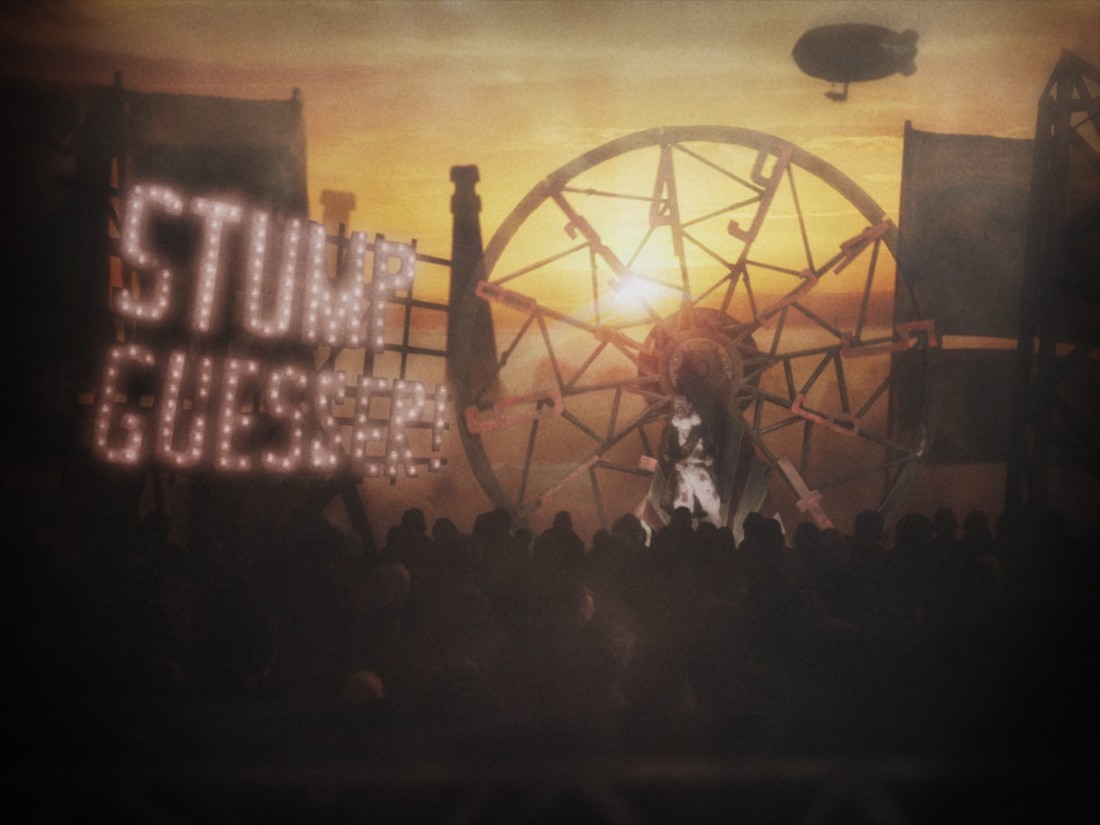

They have just completed their two most recent short films, both commissions from international arts organizations: The Rabbit Hunters by BAMPFA (the Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive) for a four-minute-long film to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Federico Fellini’s birth; and Stump the Guesser, intended to be a 10-minute-long, flexible film based on a short story by Daniil Kharms, a Russian avant-garde writer, commissioned by Ensemble Musikfabrik, a Cologne-based new music orchestra.

_1100_580_90.jpg)

1 - 4 The Rabbit Hunters, 2020, Development Ltd., Guy Maddin, Evan Johnson, Galen Johnson, 9 minutes, 12 seconds.

_1100_580_90.jpg)

2

The Fellini project turned into a nine-minute film about childhood memory and adult experience, set in a Manitoba marsh; while the Kharms idea morphed into a 19-minute film about a circus guesser working during the time of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike. In neither case did the organizers get what they thought they were getting; in both cases what they got is amazing. The films are variously eccentric, hilarious, poignant, bizarre and utterly unique. They are different from one another and even more different from anything being made today by any other filmmakers.

The projects were themselves shaped by and are containers for dreams. Both Evan and Guy keep dream journals and Evan has even developed techniques to better remember their content. Galen claims not to dream at all but has “dream-like ideas.” Maddin presents a different psychic case. “Guy will send me a 3,000-word-long dream that I have to read in four sittings,” Galen says, “whereas my eureka ideas pop into my head in the shower and they come in one sentence.”

Their research on Fellini led them to less well-known movies, like Toby Dammit, 1968, and Fellini: A Director’s Notebook, 1969. “It seemed to me he was really making mischief with that movie,” Maddin says, and Toby Dammit “was closer to something we might make as opposed to something Fellini might make.” What they found separately in the two films was the idea of dreaming and the persistence of airport anxieties. They also decided to ask Isabella Rossellini to play the Fellini character in the film, although she is never named as such. The request was not so unusual; Isabella had already played her father, the other legendary Italian filmmaker, Roberto Rossellini, in My Dad Is 100 Years Old, a film Maddin had directed in 2005 before his collaboration with the Johnson brothers.

Following that casting decision, the film developed in ways that are typical of Development Ltd. Guy wrote a script in a day and then they tacked on a dream that Evan had had the night before about unsuccessfully getting to a premiere of one of his films. “I bought my ticket and the journey to the theatre never ended, it just went on and on, through these strange places,” Evan says. “The journey in our movie is about Rossellini getting to the theatre where her film will be playing, which she never gets to.” The connection to Fellini comes through dreams as well, as he recorded them in The Book of Dreams, 2008. “All three of us have airport nightmares all the time,” Evan adds, “and so did Fellini.” The theatre ticket doubles as a boarding pass in a tidy prop transfer that brings together the two narratives. There are other shared moments: a drag queen in a big hat mimics Fellini’s Satyricon, 1969, and the look of the airport was influenced by the lighting and beauty of the airport in Toby Dammit. “Once we had taken enough flavours from Fellini to run with, we made our own movie,” Galen says.

3

4

The DL partners insist on consensus. All three adore JK Huysmans’s novel À rebours, 1884 (translated as Against Nature), and they found a way to include their mutual enthusiasm in The Rabbit Hunters. Part of Isabella’s journey to her movie premiere involves an elevator ride shared with a talkative photojournalist. The directors liked the sound of his voice and so they had him memorize a list of Huysmans’s favourite desserts, which he recites, much of the time incomprehensibly, during the elevator’s ascension. When the doors open, we see a marsh rich with bullrushes and modelled on Willow Island, a finger of land near Maddin’s summer cottage in Gimli. That’s the site of the rabbit hunting from which the film takes its title.

What the directors agreed upon with Stump the Guesser was that it be set in Winnipeg out of what they agree is hometown pride and a way of serving, as Maddin puts it, “the ongoing mythologization of Winnipeg.” While they mutually admired Daniil Kharms’s “funny, absurdist nihilist writing,” they couldn’t find anything in it that was easily adaptable. What they settled on was what Galen calls “a dark, pseudo-Soviet aesthetic that could be depressing,” which they decided to lighten by picking up the bounce of early Betty Boop and Popeye cartoons: “We were after the vibe that they have, the very specific ways that the gags unfold, the language and the signage and the labels.” The language runs the gamut from high to low; the prizes offered to anyone who can stump the guesser are pitched as “ALL SORTSA TOYS!” whereas the intertitle for an unwashed would-be stumper reads, “How many fishes have I secreted upon my person?” “We pride ourselves on the extremes,” Evan says, “so there are high-minded, even pretentious gags, and then stupid pants-fallingdown things.” At one point, a mad scientist who is trying to disprove heredity points out his remarkable findings on a blackboard; he calls them “calculations on the black square.” The reference and the scientist’s name offer a sense of how carefully considered are the script’s details. When a film set in 1919 is dominated by a Soviet-style social bureaucracy, when it names a character Flotnik and identifies him as a member of the radical Transcona Separatist Guild, and where a prize toy is a “Trotsky bear,” when that film refers to a black square, you are directed, inescapably, to Kazimir Malevich’s revolutionary monochrome painted in 1915. The scientist, Trofin Lysenko, has the same name as Stalin’s agronomist, a man whose agricultural policy was responsible for the death of millions of people. “I thought it would be funny to have as a foil character to our guesser a man who made one of the worst guesses of the 20th century, a man who didn’t believe in heredity and used it for personal and political gain to earn Stalin’s favour,” Evan says. “I think really grim things can be tragic and funny at the same time.”

1 - 4 Stump the Guesser, 2020 Development Ltd., Guy Maddin, Evan Johnson, Galen Johnson, 19 minutes, 22 seconds.

2

The film thrives on that co-existence. The idea to have a circus guesser was Galen’s, while Evan sees his mistaken guessing as “some kind of circus performer’s epistemological crisis of meaning.” At the end of the film, the guesser has to choose between two doors; behind one is his green-eyed sister, with whom he is enamoured and is determined to marry. (How the theme of incest became the engine driving the narrative is too convoluted to explain. Suffice it to say that the film includes a marriage bureaucracy that deals with the social and procedural complications of having the state overseeing claims for legal incest.) If he picks the wrong door, he must choose whatever is behind it, which is a toy tin grouse wearing a marriage veil. “One needn’t go further than the oldest member of DL for Winnipeg absurdism because it ends up with Stump the Guesser feeling that he’s been guessing pretty well, but he doesn’t guess so well on marriages,” says Guy, who applies the guesser’s choice to his own life. “I would have failed better. I don’t see it as a tragedy when he ends up with a tin grouse. He’s a little romantically disappointed but so what.”

The film tilts on a wacky axis. One of Galen’s “eureka ideas” was to have a Guessing Inspector, a bureaucrat who wanders around carrying a wooden box filled with bottles and vials and playing cards that he uses to test the guesser’s capability. When he is stumped a number of times, the guesser’s licence is revoked and, additionally, he is assigned a demerit point for incest. This kind of absurdity spins in all directions. In the name of social harmony, the marriage bureaucracy is interested in good matches, and its assessment includes x-raying the contents of couples’ stomachs; so sand in one and concrete in the other predicts marital happiness through material compatibility. The romance apparatchiks also set up a grim dance hall to assess how well couples are able to dance together. Maddin suggested that one of the challenges you would have to overcome in order to get married inside this system of state approval was to show how well you could navigate a dance floor littered with crabs. Evan calls it “a typical left-field Guy idea” that asked for an ingenious solution. “We knew we wouldn’t be able to get real crabs because it would be expensive, smelly, difficult, cruel. All those things. So we found some fake rubber crabs on Amazon, but they didn’t look real so one of us suggested that if we label them on the box as ‘real crabs,’ then maybe we could convince viewers that they were.” Evan sees the story as offering “insight into the convoluted logic of some of our gag thinking. I suppose that is one of those self-defeating jokes that doesn’t make sense but that made us laugh at the time.” Galen agrees, “There are three of us in a room and we’re basically trying to make each other laugh, so things end up in comedy even if we don’t intend them to.”

3

4

To cover the rolling credits at the end of Stump the Guesser, the partners came up with a scene inspired by a matador’s playing card that was part of a deck Galen had found in Paris in 2012 when they were working on the Seances project. It’s a two-and-a-half-minute-long, slow-motion tilt-up, shot by Galen, that starts on the guesser’s white shoes and then continues on up his body as a man’s hands tuck the hose on his left leg back into the embracing elastic of his pants. The camera moves up his flowered pants to his ornate buckle, his black sash with its string of medals, all the way to his ruffled collar. The costume is just the right amount of too much, as is the soundtrack, the Righteous Brothers crooning the lines to “Guess Who”: “Someone really loves you / Guess who / Someone really cares / Guess who / Open up your heart / In the end you’ll see / That someone / It’s me.” The guesser, now married to a tin grouse, sways to the memory of his own broken heart, a wind lightly rustles his hair and he continues to pitch his come-on role in life’s guessing game. It’s a perfect ending for an imperfect life.

In the preface to the 1903 edition of Against Nature, JK Huysmans described his protagonist as “a man soaring upwards into dream and seeking refuge in illusions of extravagant fantasy.” Stick with the over-the-top dreaming, multiply the man by three, and you’ve got the story of the unlimited development possibilities of Development Ltd.