Tomma Abts

Frayed yellow arcs glimpsed through a triangular window in steely grey, or the glistening of arthropodal segments curling around themselves, or a bubble wand folded into a comic bang and used as a loupe … Tomma Abts’s paintings can be as disarming as they are evocative. The closer you get, the more their images come apart, remnants of meticulous layers of pigment tracing across the canvas like petrified cobwebs. Those marks—false starts, armatures—give a certain volume to Abts’s constructions; they accumulate in ridges where an early layer has been filled in or changed over and over. The final image may conform to those edges or shroud them in an even topcoat, to be read only as shadows in raking light. To complicate matters further, Abts will sometimes paint trompe l’oeil effects in a single layer, giving certain lines artificial highlights or drop shadows. This all yields a push and pull in front of the canvases: Abts’s dissemblance compresses the perceived layers while specific pentimenti stretch them apart.

For her latest exhibition at David Zwirner, the painter continues to broaden her format and methods, presenting not only the classic modestly sized oils but also larger acrylic canvases and pieces incorporating multiple panels and cast metal elements. Fracture and facture seem to be the dual concerns of this grouping of 12 paintings; their surfaces slip gracefully into shards or planes of synthetic colour. In some, like the carefully modulated Ipke, 2025, it is as if the opaque top layer of oil has taken on the frangibility of glass, its hairline cracks expanding from central points of impact. That those areas of separation are delineated by a shift in the tint and order of the underlying pattern reinforces the shattered effect of the whole painting. Ipke’s canvas itself is also “broken” into two panels by a diagonal gap two-thirds of the way down its composition, which shifts the light/dark relationship between the fissures and the background, suggesting an angular change in the picture’s prismatic logic.

Many of the paintings display a similar focus on jagged lines and polygons issuing from a shared central point, as in four canvases clearly derived from the same motif. In the vastly varied treatments of Tekes, 2022, Tees, 2024, Neus, 2024, and Heerko, 2024, Abts privileged line, texture, colour and illusion, respectively—her materials ranging from spindly crayon on silk to heavily built-up layers of overlapping oil. The way that the parallel structures cohere is different from canvas to canvas as well, calling to mind, in order, radar displays, burnished armour, spinning pinwheels and mended quilts.

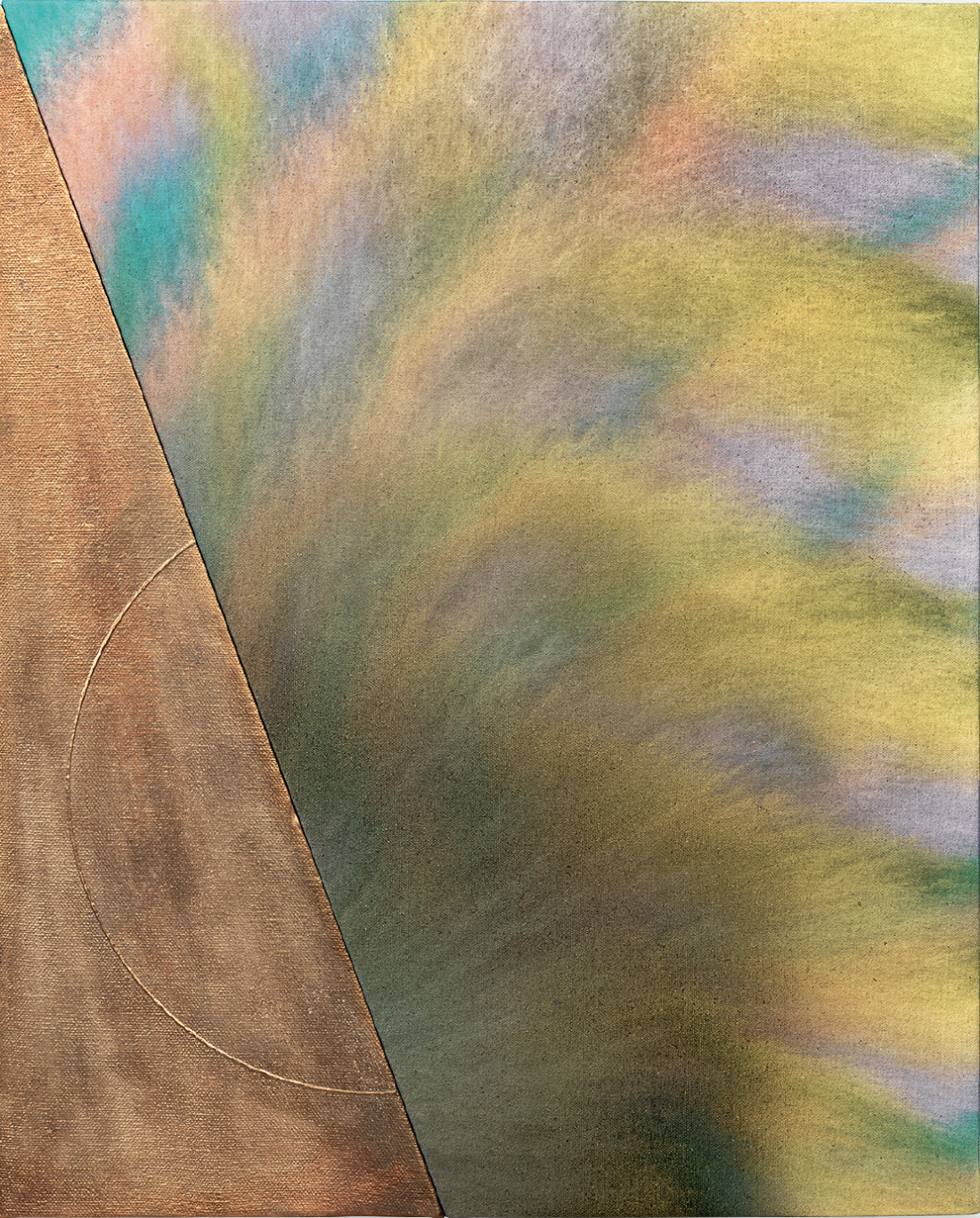

Tomma Abts, Saske, 2024, acrylic on canvas and cast bronze in two parts, 48 × 38 centimetres. © Tomma Abts. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner Gallery, New York.

It is productive to compare the less heavily worked canvases with a piece like Nanko, 2025, which employs several image-making facilities simultaneously. The homarine red composition, with its irregular radii branching off and bisecting each other, spirals out from an off-centre circle to the canvas’s four edges, creating a series of fanlike segments rushing to reconcile circular movement within a rectilinear frame. It is possible to reconstruct some of Abts’s rules for creating this structure: each spoke is linked to both its clockwise neighbour and the following spoke with lines forming obtuse angles, then at the canvas’s edge connected again to the subsequent spoke with an acute angle. With these series of overlapping and interlocking blades, the whole composition gives the feeling of an off-kilter machine, part propeller, part gearbox, its tangential relationship with the borders of the canvas creating the effect of so many millipedal feet marching up its edges. The sheer complexity of the composition with its glossy, mottled surface of troughs and planes, painted gradients and intensities of red forces its rotational movement to be read as simultaneously clockwise and counter-clockwise, similar to how the wagon-wheel effect in film causes the spokes of a wheel to appear to rotate against their true direction. Is this vision a cross-section of an axle or an aperture derived from an alien mathematics, or maybe a cellular view of some future mechanical union with organic life?

Perhaps it is easy to associate Abts’s paintings with science fiction because of their speculative formalism: when an abstract form is given depth and lighting, we are asked to imagine it in another realm—one not quite our own but still modelled after it. To build an entire lexicon in that world yields pictures with all the uncanny specificity of a Vermeer, except here there can be no camera lucida to explain the hand’s fidelity. But fidelity to what? Not vision, memory, or even imagination; to make paintings like this involves a level of trust in something somatic, outside of language.

For all the time spent looking forward, adding layers that eliminate certain possibilities while advancing others, Abts’s paintings also display a deep engagement with the past. Some motifs in the current paintings have been part of her repertoire for a decade or more, and Nanko has been in progress since at least 2016, when an intermediary stage of the painting was cast in bronze and aluminum panels, preserving its maze of ridges. Abts has continued casting canvases, resulting in a body of work that combines shaped paintings with metal elements that complete their rectangles. Saske, 2024, one of two included in the Zwirner show, is made up of a triangle of bronze abutting a canvas washed in thin acrylic. The gleaming metal has enough detail to capture the fine weave of the canvas used for casting; its only other feature is a thin circular ridge bisected by the crack between panels. On its painted half, washes of teal, pink, purple and green flow in rough arcs, feathering and blending with one another. It would be easy to offer some associative descriptions— fronds swaying in the wind, plasma in a solar corona—but in the gallery, the two-part painting insisted on its formal contrasts: solidity and turbulence, rigour and improvisation, endings and beginnings. For all the finality of its cast element, Saske is not elegiac; it takes on weight as the most straightforward step toward lightness. ❚

“Tomma Abts” was exhibited at David Zwirner, New York, from May 1, 2025, to June 14, 2025.

Louis Block is a painter based in Brooklyn.