“Tom Burrows,” edited by Scott Watson and Ian Wallace

My paintings are not about what is seen. They are about what is known forever in the mind. –Agnes Martin

Opening this book, I must also open the conversation of a city in crisis. A timely, if tragic, motivation for the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery retrospective and subsequent publication of the work of Canadian artist Tom Burrows is the sudden and surely irreversible lack of affordable housing in the city. This is a beautiful book but its subtext is ugly news. Born in Ontario in 1940, Burrows moved to Vancouver in the 1960s and studied art at the University of British Columbia, where he studied under BC Binning and met Ian Wallace, hung out with Tony Onley (his brother-in-law), Iain and Ingrid Baxter, and Glenn Topping, who was already working with fibreglass, a medium that would become a lifelong focus for Burrows. Burrows was mostly interested in abstract art, with the occasional foray into the socio-political, like many of his contemporaries of the 1960s and ’70s. Burrows came of age during a pivotal era in the academic avant-garde of art—hippies and beyond—when the city and the world was celebrating transgression in the spirit of social revolution, and he notes, “as Jack Kerouac, Leonard Cohen, cannabis and then LSD began to morph the student body/mind.” A lot has changed since then. The last decade has seen Vancouver transform from its historical identity as a perfect city for developing world-renowned artists—Ian Wallace, Jeff Wall, Liz Magor, Stan Douglas—to a city that is perfect for corrupt real estate agents.

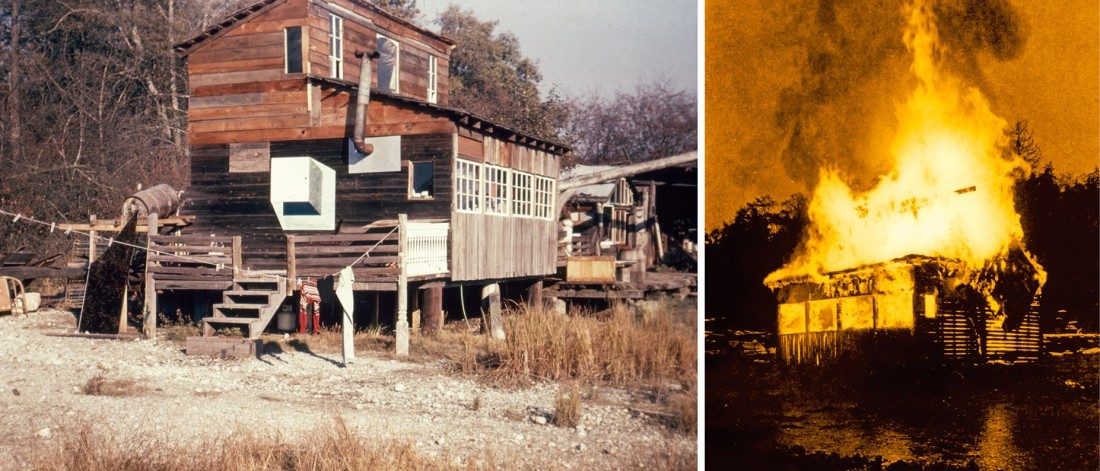

In an essay for the Guardian, local novelist Kevin Chong notes that Vancouver has become the “least affordable city in North America,” with a vacancy rate of less than 1%. Looking back at the art of Tom Burrows, we see a prophesy of this social disaster. Not more than 50 pages into this 200-page book are photographs from December 1971, when the city of North Vancouver had the squatters’ shacks on the shores of the Burrard Inlet, where Burrows lived with his wife and young child, lit on fire and burned to the ground. The home Burrows designed and built, using scrap materials, at a cost of about three dollars per square foot, was reduced to ash. Not just homes but a legacy vanished; an entire cultural history went up in smoke that day. For decades people lived rent-free in homes on these tidal sands, the Dollarton and Maplewood mud flats. Residents sometimes affectionately called this place ‘shangri-la.’ In his novella The Forest Path to the Spring, Malcolm Lowry called it Eridanus. This was where Lowry once lived more than two decades before Burrows, and wrote his novel Under the Volcano while looking out his window across the inlet to a burnt-out Shell gas sign that simply read _HELL. Lowry had written, “And everything in Eridanus, as the saying is, seemed made out of everything else, without the necessity of making anyone else suffer for its possession.” According to Burrows, the same North Vancouver home inspector who tore down Lowry’s cabin burned down his.

Left: Burrows’s house on the Maplewood Mudflats with Ivory Coast, 1968, installed on the west wall, c 1969–71. Right: Burrows’s home, set on fire by the District of North Vancouver building inspector, December 1971. Jerry Williams photographed the burning house on black and white film, and Burrows later coloured it. Photographs from the collection of the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery Archives, Tom Burrows fonds.

The house Burrows made from scrap, and the art he made while there, form the centrepiece of this book. Burrows was critiquing real estate with site-specific art surrounding his site-specific home. Or, as curator Scott Watson puts it in his essay, “The panel produced the house and the house produced the sculptures. The mudflat sculptures made from local materials were transformed daily by the rising tide, which isolated and mirrored the pieces, further abstracting them through symmetry.”

Let’s flash forward to 2008, the year America’s unregulated subprime mortgage industry triggered a massive financial market collapse that cratered much of the world’s economy, and the year Vancouver’s tallest hotel and condominium opened for business. Rising up out of the ground just a few blocks away from the Vancouver Art Gallery, Shangri-La is a 62-storey glass sword, and was, even in the five years of its construction, a symbol of everything that was changing about the city. Often ignored as a backwater colonialist port town, Vancouver humbly thrived for 100 years, exploiting its natural resources and ocean access. The shangri-la of the Dollarton squatters’ shacks was emblematic of the overlooked, underappreciated side of Vancouver, and this downtown Shangri-La is the latest iteration of its exploitation. Land has always been a contested commodity here. Stolen or ill-gotten, Vancouver real estate is a legacy of dispossession, gentrification and commodification. In 2010, the year Vancouver hosted the Winter Olympics, the Vancouver Art Gallery invited Ken Lum to produce a work for their off-site public space, which happens to be right across the street from the Shangri-La. Lum created the site-specific work from shangri-la to shangri-la, which featured one-third-scale models of three squatters’ shacks from the North Shore mud flats—that vanished shangri-la—right across the street from the new Shangri-La. Over a polished floor meant to resemble still water were Lum’s replicas of Malcolm Lowry’s cabin, the shack residence of Paul Spong (scientist and leader of Greenpeace’s “Save the Whales” campaign) and Tom Burrows’s home. Here, the two shangri-las squared off: the new gleaming Shangri-La of one-percenter wealth and conspicuous consumption versus the idealistic shangri-la of anti-establishment squatters. The mud flat shangri-la, a utopian community on precarious land, a tidal zone, was a living contradiction to the belief in land tenure that makes a high-rise like Shangri-La such a capitalist fantasy. These tiny shacks on stilts made from scrap wood, humble to begin with, humbled even more by Lum’s diminished scale, are really brought down to size in contrast to the prosperity of their surroundings on glamorous West Georgia Street. Nevertheless, the little shacks held their ground.

In an act of utterly offensive neo-liberal irony, the city of North Vancouver later purchased Lum’s sculptures and installed them permanently on the same mud flats where they onced burned down the actual homes and evicted the inhabitants. Ken Lum was right to accept their offer to buy the installation, just as the city was wrong to ever demolish the original squats.

Kevin Chong’s essay for the Guardian begins with the tragic story of a homeless man in his mid-70s with terminal cancer, named Ted, who spent his nights in a 24-hour Tim Horton’s doughnut and coffee shop. No one noticed he was dead. “Staff were so used to Ted that they needed to be convinced to call 911,” Chong writes. “An ambulance took Ted to Vancouver General Hospital, where he was officially declared dead. His friend said he overheard a paramedic speculating that Ted might have been dead for 12 hours.” This is an especially egregious example of Vancouver’s inhospitible treatment of the poor and homeless. In his essay, Chong mentions a few more alarming statistics that account for this devastating indictment of Vancouver’s housing crisis, including a 25% rise in homelessness between the years 2015 to 2018. “More seniors live in poverty (8.8%) in British Columbia than anywhere in Canada,” Chong writes. The average price of a home in Vancouver is now $1.4 million. A one-bedroom apartment rents on average for $2,060. There is no idyll here anymore.

Money laundering helps account for the disparity between the average household income of $72,662, and the cost of housing. Owning a home has become a fantasy for typical citizens after years and years of criminals’ taking advantage of a poorly regulated real estate market. A headline from November 2018 says it all: “Secret police study finds crime networks could have laundered over $1B through Vancouver homes in 2016.” Because it’s not just drug cartels and gangs, it’s the so-called white-collar criminals we learned about in the Panama Papers who funnel money through offshore banks, back and forth through real estate transactions, cleaning untaxed income and profiting exponentially while the rest of us pay for it. Money laundering is a multi-billion-dollar industry in the province and the loss of annual taxed revenue jacks up prices on everything else. From the cost of a coffee and a doughnut, to groceries, to the electricity bill, to property tax, inflation is inevitable when there’s this much exploitation. Under these conditions, decency suffers. Honesty can’t survive. Creativity dies.

“Burrows was prescient in his work on houses and squats, with his emphatic use of recycled materials and his attention to context and environment,” writes Watson. “The current housing crisis in Vancouver—which may soon entirely deprive young people working in the arts—is the result of a long-term trend that began when condominiums, unknown in this region until the 1970s, began to dominate new housing inventory. Housing is now so expensive here that it contains and circumscribes the possibilities of living a free life, as people must use an ever-greater percentage of their income to pay for shelter.”

“A work of art can be a home, a sculpture on a pedestal of pilings above the tidal waters of the mudflats,” writes artist Ian Wallace in his essay on Tom Burrows, featured in the book. It is mainly because Ian Wallace photographed Burrows’s home on the mud flats that we have documentation of his time there. The two artists studied together at UBC in the 1960s under the mentorship of BC Binning.

Looking at this book, I keep thinking outside of it, about homes and homelessness, and about the artist Agnes Martin. Born in Macklin, Saskatchewan, in 1912 and raised in Vancouver, where her life as an artist began, Martin turned to abstraction in her 20s while living in New York, then spent the rest of her life mainly in New Mexico. It seems she was most at home in relative solitude.

The ocean is deathless

The islands rise and die

Quietly come, quietly go

A silent swaying breath

I wish the idea of time would drain out of my cells and leave me quiet even on this shore.

Martin might have been thinking of her painting Night Sea when she wrote that, but it’s as if she’s writing about life on the Dollarton mud flats. In a lecture Martin delivered at Cornell University in January 1972, a month after North Vancouver burned Tom Burrows’s home to the ground, she concludes: “The development of sensibility is the most important thing for children and adults but is much more possible in children. In adults it would be more accurate to say that the awakening to their sensibility is the most important thing. Some parents put the development of social mores ahead of aesthetic development. Small children are taken to the park for social play; sent to nursery school and headstart. But the little child sitting alone, perhaps even neglected and forgotten, is the one open to inspiration and the development of sensibility.”

Vancouver needs to be that child sitting alone. Vancouver needs to be neglected. Clearly the guardians of this child-city are bad for its growth. Better to be forgotten than exploited. Better to be forgotten and find inspiration and sensibility.

In the 1960s, Burrows was practising formalist abstraction on sheets of fibreglass. He saturated polyester resin panels with colours. Glass-like and sculptural—the panels are devoid of context, there is no reference, they are not images of the sky, of heavens, or nebulae, just pure image. Like Sol LeWitt, Ellsworth Kelly and fellow Canadian Agnes Martin, in Tom Burrows’s work there is an ambient quality that is resistant to interpretation even while it is resonant and meditative. In his essay that opens the book, curator Scott Watson quotes Burrows as saying that “what is most important is not so much to make an abstract statement in a shape or form deriving from, or reflecting something else, as to produce a real object that doesn’t reflect on anything, doesn’t say anything, doesn’t produce anything, doesn’t stop the wind, but is just there, holding space: a genuine presence, a thing in itself, unique and useless.”

After Dollarton, Burrows and his family moved to Hornby Island, built another house, and in 1989 he took up fibreglass abstraction again. Watson writes that “at the age of fifty, working at a back-breaking construction job in Toronto and having sold only one piece in the past decade, Burrows was determined to return to polymer, and decided that his open-air studio on Hornby Island offered a safe way to work with the material.” Burrows imagines them as sculptures, and aside from some works from the ’60s like Studies for Conjugality made of enameled, warped plywood, his artwork is about as sculptural as Donald Judd’s boxes are painterly, which is to say that the identification is valid even if it is a bit of a misnomer. Borrows has more in common with Agnes Martin and Joan Mitchell than he does the land artist Richard Serra or sculptor Robert Smithson, and there’s a greater kinship to the geometric abstractions of BC artists Gordon Appelbe Smith and John Dobereiner than to the minimalist objects of Americans like Dan Flavin and Carl Andre. It would be hard to fairly connect Burrows with a sculptural lineage, as opposed to the easier-to-discern influences of Kasimir Malevich, Kenneth Noland, Mark Rothko and Ad Reinhart. Burrows has no ulterior motive in these panels. The later works, from the late 1990s and this century especially, are monochromal and contemplative. There is no subject. They are what they are and nothing else, doing nothing, signifying nothing. They are not decorative because they are disinterested in decoration. They are as indifferent to purposeful beauty as to intellectual dialectic. Over the decades, Burrows shifted his focus to more overtly political work, art with a direct social commentary. But unlike an artist such as Adrian Piper, polemics and rhetoric come and go in Burrows’s catalogue, as opposed to acting as an enduring commitment to social justice and as a challenge to the status quo of the gallery.

Of his work, Burrows says, in his essay for this book, “The resin-and-glass fibre medium allows for any pigment density, from completely opaque to the thinnest watercolour-like wash, but itself translucent, i.e., if you hold your hand behind a piece, it can be seen wherever its image is not blocked by pigmentation. A 45-degree return edge on the sides of each piece suspends its face surface one inch off the wall on which it hangs. This allows light to pass through the work and bounce off the surface behind it.”

Watson writes, “The regularity and often-monochromatic colouring give the panels something of the serenity and aloof demeanor of Agnes Martin and Ad Reinhardt, two artists Burrows admires.” The works are also described like pools on the sandy Dollarton hardpan. Tide puddles, reflecting the shifting skies above while revealing the ground below, shimmering thin sheets of inlet water. In this way, Burrows himself is reminded of his old squatter’s home on the mud flats in these multi-hued abstractions that he makes out of liquid polyester. In a couple of decades he’s used less fibreglass than it takes to “fabricate the hull of a mid-sized Coal Harbour yacht.”

There is an ending. It ends in the same hopeless struggle between art and commerce as it began. Or, as Burrows puts it, “I am amazed that polymer resin in the format that I initiated in the late 1960s has kept me engaged for the past two decades. I suppose it is the elusive quality of the material process…. Of course the money helps, but even then you never know. Poker chips on the flat plain of capitalism.”

“Why had these shacks come to represent something to me of an indefinable goodness, even a kind of greatness?” wrote Lowry in his novella The Forest Path to the Spring. “And some shadow of truth that was later to come to me, seemed to steal over my soul, the feeling of something that man had lost, of which these shacks and cabins, brave against the elements, but at the mercy of the destroyer, were the helpless yet stalwart symbol of man’s hunger and need for beauty, for the stars and the universe.”

Tom Burrows, edited by Scott Watson and Ian Wallace, Figure 1 Publishing, 208 pages, hardcover, $50.00.

Lee Henderson is a contributing editor to Border Crossings. His most recent novel, The Road Narrows as You Go, was published in 2014 by Hamish Hamilton.