Tina Girouard

Walking between two New York exhibitions by Cajun artist Tina Girouard, I heard the soundtrack from the 1970s film Saturday Night Fever playing twice—first in a rundown diner, then again in a crappy drugstore. Echoes of the decade felt right, as restored context for the city’s (and the era’s) profound dysfunction and a reminder of the historical turn to performance as an aesthetic and political strategy. Yet, the exhibitions offer another take on the moment. Perhaps Tina Girouard is best remembered for her foundational work in SoHo, setting up artist-centred spaces like 112 Greene Street (later White Columns) and FOOD restaurant. Her work appears as a fever dream of doing and crafting, gathering and connecting, alive with energy and marking a lifelong feminist practice whose contours inflect much of contemporary art thinking today.

Tina Girouard, installation view, “I Want You to Have a Good Time,” 2024, Anat Ebgi, New York. Courtesy the Estate of Tina Girouard and Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles/New York. © Estate of Tina Girouard, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

At Anat Ebgi gallery in Tribeca, “I Want You to Have a Good Time”—a phrase borrowed from her performance work Sound Loop, 1970—captures both the fun and the critique of her oeuvre, as well as its deep generosity. Built around a small collection of performance scores, photographs and video documentation, the exhibition at once emphasizes the productive forms of composition and choreography— play, enactment, the everyday—that motored so much of the avant garde circa the 1960s, while testifying to Girouard’s distinctive choice and exploratory use of materials. An installation of tape decks and audio equipment stands at the centre of the gallery, used to reconstruct Sound Loop, wherein a performer speaks into a microphone that records words to tape, which then loop and layer until singular sounds and meanings are no longer legible. I missed the reconstructions at Anat— featuring Erin Leland, Tyler Coburn and Ken Castaneda—but loved seeing the audio equipment and related scores that beckoned participation and the notion of sound on the brink of communication.

Video documentation of several performances—grainy, black and white—recall the DIY vibe of the moment: Maintenance II, 1972, follows Girouard as she cuts her hair, while reflecting on style as transformation and recounting everyday goings-on to an off-screen presence. The camera holds her close; the mood is intimate—it’s a new kind of portraiture, where proximity and duration offer surprising shifts in identity, and the idea of upkeep, as opposed to the “new,” reads both as imperative and devotion. A threeminute clip of Swiss Self, 1976, offers a portrait of a different order, drawn through action and symbol alone. We see the artist enter the frame and stand on a patterned floor of patiostyle rocks; she looks up towards the camera with clasped hands. She lays down a carpet, crawls across, mountain- climber style, pulls back its edge to peer under, then lies on her back, arms splayed as if in surrender. In the next shot, she begins to unfurl and lay out patterned fabric (florals), first making a cross, then holding a looped object up to the camera—a bell? a key fob? an infinity ribbon? Finally, she places another fabric over the cross, arranging it in a diagonal, as if to cancel out the ease of the cross’s right angles, the trap of the corner, unlocking potentiality.

Tina Girouard, installation view, “SIGNIN,” 2024–2025, Center for Art, Research and Alliances, New York. Courtesy the Estate of Tina Girouard and Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles/New York. © Estate of Tina Girouard, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Then I watched a clip of W.A.W.A., 1979, an acronym that stands for “worker, aristocrat, witness, agent.” Exactly. A collaborative assemblage for eight people with bolts of fabric, plants and a horn player, the video shows the performers working together in pairs to unfurl and billow fabrics into different shapes: an X here, a solar ray there, and finally a hashtag, arranged as if to mark off the performance space as ritual altar. In the hashtag square, the group adds plants to make an X in the centre. Is it a meeting point that marks all performance as social space? Or a statement about beauty as practice, important for how it invites perception and community? Overall, the videos offer a glimpse of an artist working the power of familiar materials and pointing to the body as regal agent and the social as especially critical to that agency.

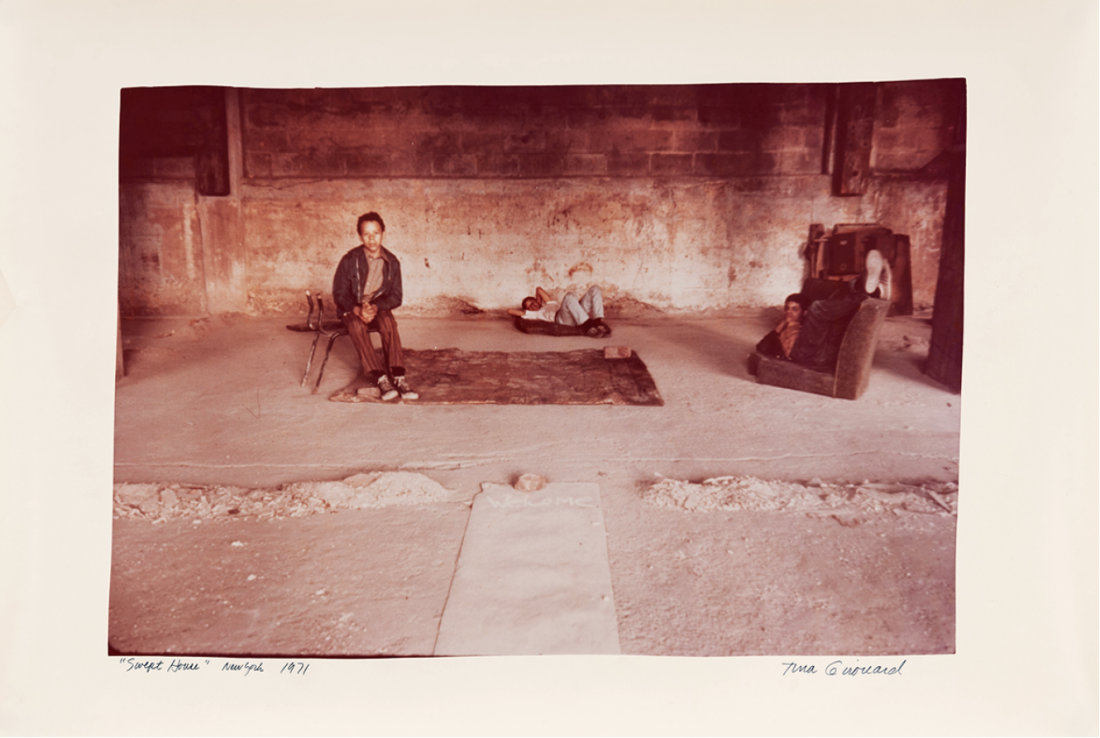

I moved on to the second exhibition at the Center for Art, Research and Alliances (CARA) for “SIGN-IN,” a comprehensive show of striking objects presented alongside notebooks, drawings and photographs arranged in small vitrines at a digestible scale. On the first floor, curators have hung a wall-sized photograph of Girouard’s performance of Swept House, 1971—in which she swept the trash under the Brooklyn Bridge to form the shape of a home—close to Maintenance I: Take One Role Change (Part 1), 1970, melding care of the environment with care of the body and recalling Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s maintenance manifesto and work from the same period. In front of Swept House were two works from her “DNA/Signs/ Pictionary/Glyphs” series, bold sewn fabrics showing four of the 400-some original glyph vocabularies she created during the late 1970s and early 1980s. A burst of colour, aligned with pattern play and rupture, the crafted feel of the glyph work testifies at once to the affective labour associated with women’s work and the more-thanlinguistic, visual and gestural nature of communication. Equally, they prefigure her work in the 1990s, when she moved to Haiti to study Vodou flag beading and make work with Antoine Oleyant and Georges Valris, producing several dazzling large-scale pieces on view at CARA as well as a book, Sequin Artists of Haiti, 1994.

Tina Girouard, Swept House (New York), 1971, chromogenic print, 52.07 × 75.9 centimetres. Courtesy the Estate of Tina Girouard and Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles/ New York. © Estate of Tina Girouard, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Textiles feature centrally in the array of compelling objects on view here. A sweep of fabric, suspended between the first- and secondfloor galleries, makes use of the “Solomon’s Lot fabrics” (1970s), bolts of 1940s patterned silk given to her mother-in-law by a relative, a salesman named Solomon Matlock, that were used and reused by Girouard across many performances and artworks. At CARA, the fabrics’ faded colours and weighted draping seem to radiate everyday use and memory—a kitchen towel drying on the back of a chair, clothes hanging from a laundry line in the alley, curtains rippling in a summer breeze. On the second floor, Lie No, 1973, shows four strips of worn, patterned linoleum, placed in a square. Above, mirroring the square and like a tent, four strips of fabric hang suspended, making a sheltering swag in what is a reconstruction of Air Space Stage, 1972. Nearby, Hung House, 1971, is a minimalist sculpture, featuring a cot, plywood and a suitcase. Altogether, the installation testifies to the beauty of pattern and decoration—the artistic movement her work became associated with— and an ongoing preoccupation with ideas of domestic labour and community service.

But even more than textiles and objects, the exhibitions foreground relationships and the generative, world-making power of the collective. Girouard’s work recalls much of second-wave feminist art history with its performances of sweeping, washing, maintaining, or sewing, beading, crafting and working, and its use of ordinary materials—textiles, linoleums, wallpapers, sequins, found objects, vernacular language. But it is her prioritization of the social—as a builder, organizer, supporter and collaborator— that seems most prescient (and necessary) today. While she was in New York (1969 to 1978), her foundational work and friendships with productive movements and figures of the day—including, for example, the Anarchitecture Group with Carol Goodden, Gorden Matta Clark and Laurie Anderson among others—foreground her role as instigator and developer of infrastructure. She relocated to Louisiana in 1978, where she founded the Artists’ Alliance in Lafayette and created the Festival Internationale de Louisiane. Her work of this order prefigures the critical attention to social practice and relational approaches that today serve as a core methodology. If feminism’s singular contribution to art history has been what curator Catherine de Zegher calls its “aesthetics of relation and reciprocity” (Artforum website, 2003), Girouard’s work and life story constitute a primary, exhilarating example. ❚

“Tina Girouard: I Want You to Have a Good Time” was exhibited at the Anat Ebgi, New York, from September 6, 2024, to October 19, 2024; and “Tina Girouard: SIGNIN” was exhibited at Center for Art, Research and Alliances, New York, from September 20, 2024, to January 12, 2025.

MJ Thompson is a writer and teacher living in Montreal. She writes about dance, performance and the visual arts.