“Time of Others”

The product of a collaboration between artists, curators and galleries in Tokyo, Osaka, Singapore, Queensland and Brisbane, “Time of Others” is a group show that examines place, identity and ideas of the other with a specific focus on the Asia-Pacific region. Rather than treat the region as a singular, homogenous whole, the show highlights intersections and complexities within a mosaic of different, and often differing, histories and cultures. There is a lot of heavy subject matter at hand: occupation, buried histories and ghosts of brutalities past. These are smartly negotiated by a largely younger generation of artists whose aesthetics and politics work in tandem, largely dodging the pitfalls of being too simplistic, didactic or impenetrable.

Censorship and state suppression loomed large in the show; Kiri Dalena erased the text from banners and picket signs in archival photographs of public demonstrations in 1950s–’70s Philippines, bringing to mind today’s alarming trend of governments revising or negating history and white- washing textbooks, while Minouk Lim introduced International Calling Frequency, 2015, a lyricless la-la-la protest anthem created to sidestep laws against public protest in South Korea. The copyright-free melody aims to go international with a video of the song used in small street protests and a stack of bilingual handouts with the sheet music on one side and a list of possible circumstances in which to sing the subversively catchy earworm on the other. Thai painter Natee Utarit’s technically impressive Birth of Tragedy, 2010, employed the conventions old European still-life and vanitas painting as a wink-nod workaround to Thailand’s “lèse-majesté” (injured majesty) law, where any perceived insult to the monarchy (read: criticism) can land you in serious trouble. Here, a skeleton on a table is flanked by mysterious, presumably symbolic objects. A headless angel, model eyeball and a bust facing away from the viewer all seem to be deployed strategically.

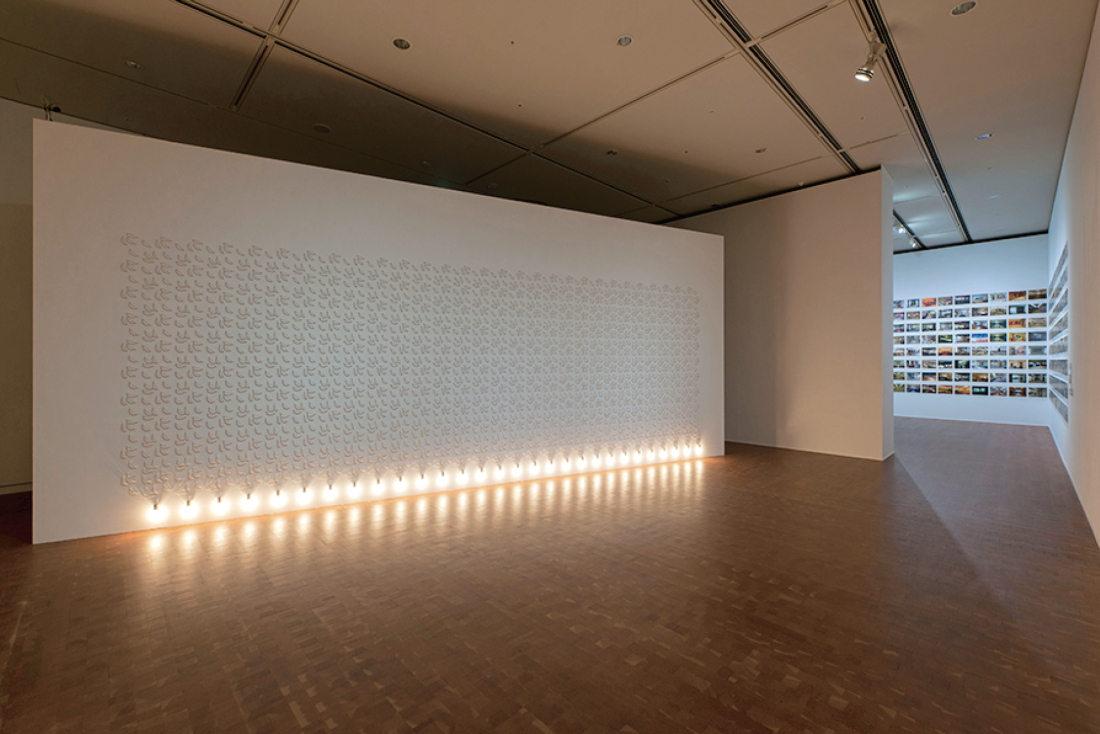

Jonathan Jones, lumination fall wall weave, 2006/2015. Photograph Kazuo Fukunaga. Courtesy The National Museum of Art, Osaka.

Ho Tzu Nyen’s video installation The Nameless, 2014, was one of the exhibition’s strongest works. It’s a tight, 20-minute collage of scenes featuring dapper Hong Kong movie star Tony Leung culled from notable works of contemporary Asian cinema, while a voiceover tells the story of Lai Teck, a higher-up in the Malayan Communist Party and triple agent who spied for France, Britain and occupying Japan under as many as 50 different aliases. Simultaneously disorienting and compelling, familiar flicks are mined and recombined until Leung becomes Teck, a singular continuous figure in the narrative, exiting one room in, say, Ang Lee’s Lust, Caution, then entering another in Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love like a quick-change artist. Video installations generally keep people’s attention for a few minutes tops, but many gallery-goers seemed riveted by the double-screen montage and 12-channel sound design, some staying for second, even third viewings. Pity that it got banned from the 2014 Shanghai Biennale.

Elsewhere, Vo An Khanh’s stark, arresting press images from the Vietnam war prompted a mental scan of all of the “Nam” movies and PBS documentaries I’d seen over the years. Growing up in North America, the story was almost always told from the American perspective, with rare, brief glimpses of it from the “other” side. Saigon-born former refugee An-My Lê’s sharp, quiet large-format photographs of latter-day US troops at work and rest paired well with Futoshi Miyagi’s American Boyfriend: The Ocean View Resort, 2013, a video based on the secret relationship between the protagonist’s grandfather and an American Soldier in Okinawa during WWII. The backdrop of slow, almost-static images of breezy palm trees and gently lapping waves belies Okinawa’s history as a deeply-contested territory. Annexed by Japan, the site of countless horrors in WWII, the former Ryukyu kingdom and now Japan’s poorest prefecture is an azure water and white sand paradise littered with unexploded ordnance, dependent on tourism and the presence of US military bases. I visited Okinawa last year, and you can sense the ghosts and sorrow in the soil.

Pratchaya Phinthong, Give more than you take, 2010–ongoing. Photograph Kazuo Fukunaga. Courtesy The National Museum of Art, Osaka.

Similar ghosts are addressed in Vandy Rattana’s haunting video MONOLOGUE, 2015. Drawing from Cambodia’s history, a narrator speaks to the bodies buried beneath the rice paddies and the mango grove where the camera stands. In Shitamichi Motoyuki’s Torii Series, the artist located and photographed abandoned Japanese torii gates in formerly occupied territories like Saipan and Korea. Erected as symbols of divine rule during Japan’s brutal imperialist period, the structures native to Japan’s Shinto religion are drained of their political and spiritual force; weather-beaten, overgrown by green, or as pictured in Taiwan, lowered and used as a park bench.

Unfortunately, I can’t discuss every artist in the show, but other noteworthies included Give More Than You Take, an ongoing work where the weight of Pratchaya Phinthong’s temp labour as a berry picker (549 kg to be precise) is converted into the equivalent weight of works from each exhibiting gallery’s collection, and displayed; Danh Vo’s 2.2.1861, a facsimile of a letter written by a 19th-century French missionary awaiting execution hand-traced by the artist’s father; Salah Hussein’s cluster of 100 small paintings exploring the little-known history of Arab-Indonesians; while the social turn is reflected in Tsubasa Kato’s ongoing series of cathartic, jubilant video works where residents of a chosen site construct, raise, pull down and destroy a large wooden structure.

Overall, the show cast a glare onto the limitations of my own knowledge, acting as a springboard to do more research on places I knew only the basics about, while serving as a grim reminder of imperial/colonial histories and violence that constantly hums beneath the surface of things. In terms of my own ideas of otherness, they remain personal, slippery. As part of the small percentage of gaijin (外人: foreigner, literally “outside person”) living in Japan while hyper-connected to the rest of the world through technology, certain ways of knowing and seeing I’ve carried over are under constant reassessment. This exhibit added to an already-welcome muddle. That said, I’d love to see this show cross the ocean. I’m curious how it would be received in North America. ❚

“Time of Others” was exhibited at The National Museum of Art, Osaka, Japan, from July 25 to September 23, 2015.

Christopher Olson lives in Nara, Japan.