Tim Gardner

In early October, something of an art world rarity occurred: a major international artist, represented by one of the world’s top galleries, launched a new series of work on the (seemingly) new theme of the whisky bottle at a small gallery in Winnipeg, Manitoba with a reputation of modest to none. Coincidentally, another rare event occurred that same month in the town of Gimli, Manitoba with reverberations through the international whisky market, oddly linking the worlds of whisky, art and commerce.

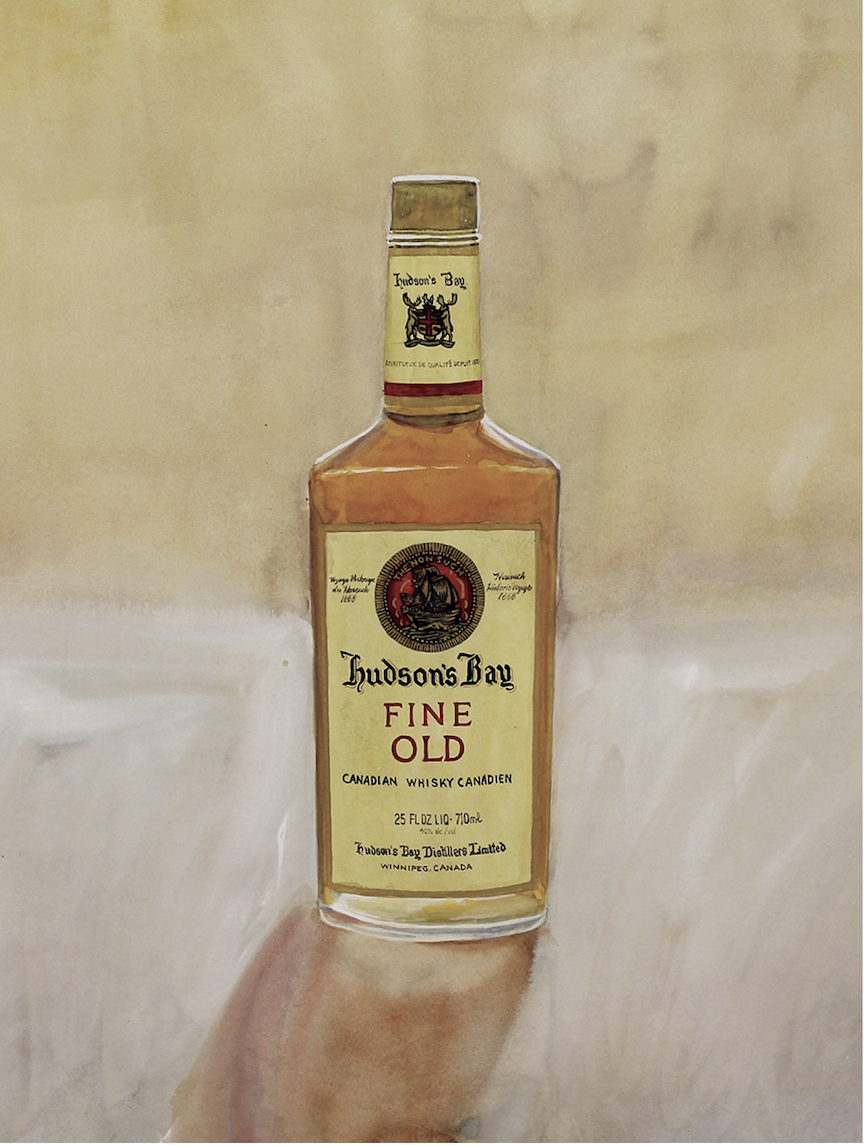

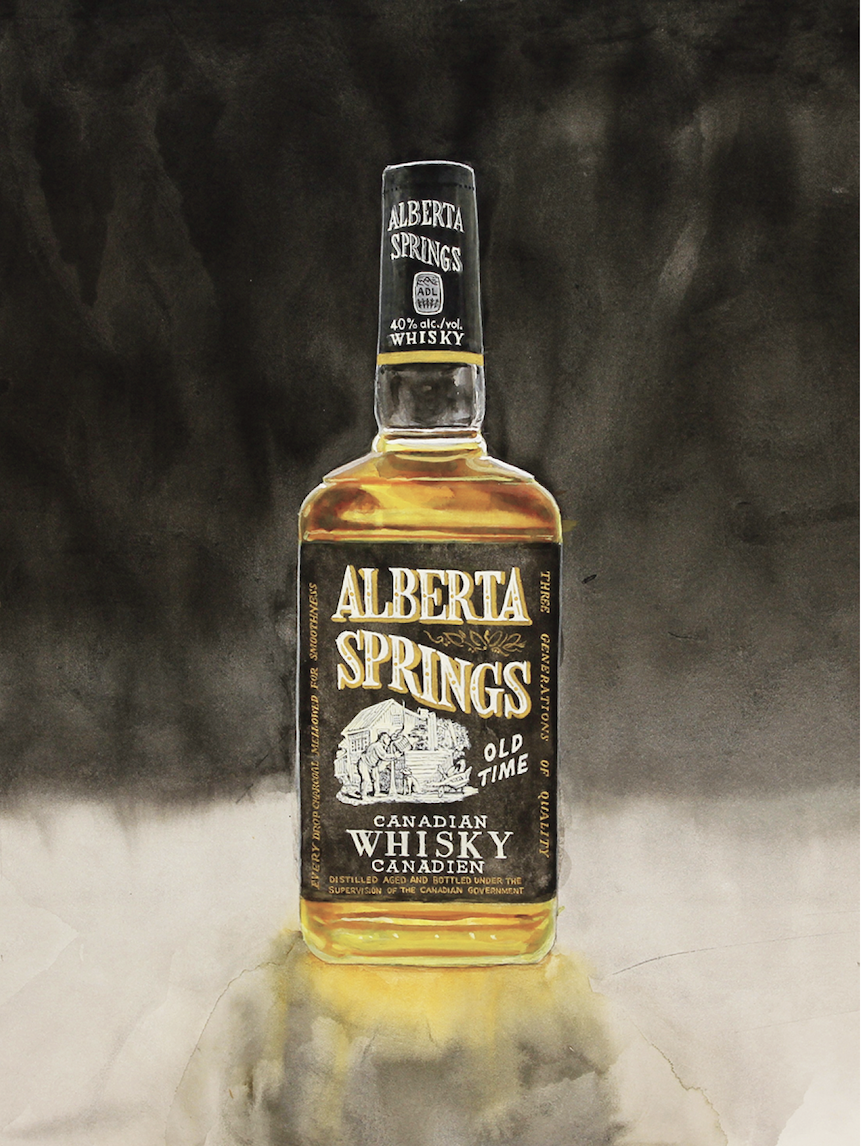

Tim Gardner’s show at LANTERN is comprised of 12 immaculately rendered still-life watercolour paintings of individual Canadian whisky bottles. The works play on a simple tension between a loose background wash and the meticulous treatment of each vessel, realized with razorsharp precision. Glancing along the narrow corridor of gallery walls, a Rothko-esque sensation of fuzzy, abstracted colour emerges, punctuated by glowing amber jewels. The formality of the presentation instills a muted reverence (also akin to Rothko), but the polarized palette of chilly blue/grey alongside caramel browns and golds lends the feeling of a warmly lit corner bar. You can almost hear the ice cubes tinkling convivially in a lowball glass.

Tim Gardner, Hudson’s Bay Fine Old, 2015, watercolour, 16 x 12 inches, © Tim Gardner. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

In a statement accompanying the exhibition, two important bits of information emerge: first, that the impetus for this show derived from a longstanding friendship between the artist and the gallerists; and second, that the bottles represented in the series were discovered by the artist and his wife among the effects of his wife’s late grandfather, who was the owner of a long-standing neighbourhood bar in Winnipeg’s Cambridge Hotel. This last bit of personal history is pure Gardner; what may seem straightforward at first glance is suddenly imbued with a whole host of deeper currents. The paintings appear to be a purely technical exercise but are revealed to encode an emotional language that speaks of culture, history and memory. The bottles are more than random subjects, and their specificity is most clearly demonstrated in their origins: Canadian, one and all. This too is vintage Gardner, an artist who has never turned his back on the past.

The artist’s career officially began with large paintings detailing the inebriated carousing of a young Gardner and his hoser friends; a lot has changed since then. In a feat of technical wizardry, he went on to carefully replicate—in watercolour— the equivalent of whole albums of family photographs—staged portraits, souvenir snapshots, and those intimate moments in the life of a family that seem benign at a glance, but are loaded with what can only be described as the weight of time. An ongoing deconstruction of masculinity and its outward manifestations in the larger culture also became a continual thread through his work. In recent years, abstraction has crept in, and an experimentation with media and substrates (most notably, chalk pastel and paper towels).

Tim Gardner, Alberta Springs, 2015, watercolour, 16 x 12 inches, © Tim Gardner. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

In 2014, another invitation from an old friend/fellow artist/ newly minted gallerist led to a similarly unexpected, off-the-grid kind of show at an upstart gallery in downtown Los Angeles. This show marked a strong departure from the photorealistic tradition with which Gardner has been so closely associated: a series of abstractions consisting of patchwork blocks of paper towel soaked with watercolour, the detritus of the artist’s studio reconfigured. Gardner has referred to the LA show as immensely freeing; the Winnipeg show marks a similar return to a place formerly called home, and another opportunity to break with expected themes.

The surprise and aptness of the LANTERN show lies with what this new series actually represents: the mature artist revealing his course on a continuum of growth. Time and again, Gardner has invested his work along themes of men and drink—young men on a bender, older men at leisure, working men, and college boys losing their heads. The intoxicating quality of his earliest works—the heady rush of youth and its heavier treatment in swirls of oil paint on canvas—has been honed to its barest concept. We are left simply with the bottle, in all its permutations and refractions, loaded with the weight of numerous histories: artistic, cultural, personal.

Installation view, “Tim Gardner,” 2015, LANTERN, Winnipeg. Courtesy LANTERN.

In a strange coincidence, during the final days of Gardner’s LANTERN show, Crown Royal’s Northern Harvest Rye Whisky was declared 2016’s World Whisky of the Year by the influential Whisky Bible. Northern Harvest is produced at a distillery less than two hour’s drive from downtown Winnipeg in the tiny town of Gimli, Manitoba; its surprising win rocked the world of whisky critics near and far. In a prestige market dominated by “premium” single malt scotches, Canadian rye has been the proverbial tortoise; it has a reputation for quality that is somewhat offset by its traditionally humble market position. Crown Royal has long played on its association with royalty to elevate its brand status (most obviously, its name and the imagery on its label, as well as its original presentation in a purple velvet drawstring bag), having been founded to commemorate the first tour of Canada by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in 1939. In fact, as Gardner’s selections show, the labelling of most Canadian rye whisky determinedly relies on those stock versions of Canada and its symbols so beloved by advertisers: Krieghoff vignettes of sugar shacks and sleigh rides (Canada’s own Currier and Ives); Hudson’s Bay; Alberta Springs with its evocations of glaciers and Rockies.

Northern Harvest’s unlikely designation as the world’s best is underscored by the fact that it is not produced as a limited edition, does not boast a long aging process, and has a decidedly democratic price point. While none of these attributes could be associated with a Tim Gardner painting, there are some parallels here nonetheless: the triumph of the new, which is actually a crystallizing of past ideas; a resistance to the pressures of market forces and expectations, in the hope of achieving something different; and the simple celebration of a hometown hero. Gardner’s process towards the new imagery in his show has been a lot like the process of distilling a fine whisky: the larger (narrative) elements reduced to a basic, but perfectly described essence.

On that crisp fall evening in Winnipeg’s Chinatown, the art crowd wasn’t shocked by the new—they saw just what they have come to expect from an old friend and colleague with a formidable talent obvious long before the fame that followed. More significant was the message implicit in this event which has continued to reverberate in minds and hearts well after the close of the exhibition’s brief run: history matters. ❚

Tim Gardner was exhibited at LANTERN, Winnipeg, from October 2 to October 30, 2015.

Christabel Wiebe is an independent writer, editor and curator based in Winnipeg.