“Through Lines”

Redaction (along with its bedfellows censorship and erasure) may be the archetypal bugbear of democracy—one only has to point to examples like Joseph Stalin’s excising disfavoured figures from Soviet history to stir up fears of state paternalism and oppression. Nevertheless, the increasingly fraught political and media landscape of today’s West may also be prompting a kind of redaction renaissance. As free speech is rebranded into a right-wing dog whistle, socially minded activists are embracing a variety of mechanisms—including no-platforming, the de-installation of controversial public monuments and the direct censorship of fake or overtly partisan news—designed to limit the dissemination of certain popular ideologies. Even on a personal level, I’ve found myself compelled to shake up academic and social media echo chambers by consciously revising which cultural sources I consume. Despite the emotional pitch of redaction’s more public forms, it’s this private dimension that sticks with me. How is it that redaction, infamous for its use in manipulating societal attitudes, can also bring about individual growth and transformation?

In her curatorial essay for the Koffler Gallery and Critical Distance Centre for Curators’ “Through Lines,” Noa Bronstein is right in suggesting that redaction is of particular importance to artists—not only because of their historical concern for social justice, but because artistic practice looks beyond the question of what realities are recorded to how they are remembered and understood. Turning the tables on redaction is hardly new to the arts: while William Burroughs’s cut-ups sought to revive the repressed ultra-reality of mid-century news media by using its own processes of omission and disjunction against it, his successor Tom Phillips celebrated civil and sexual liberation by drawing, painting and collaging over 19th-century conservative tracts. “Through Lines,” however, proposes that remaking redaction for the 21st century means more than simply updating its ideological commitments. Rather, the show highlights how the covered-up, the cut-off and the simply not-there shape not only our access to information, but also the epistemic and aesthetic subjects who absorb and act on it—in other words, us.

Nadia Myre’s Indian Act, visible on Artscape Youngplace’s outdoor billboard and inside at the Koffler Gallery, is both the show’s oldest work and its conceptual anchor. First exhibited as part of “Cont[r]act” at Montréal’s Oboro Gallery in 2002, the work features all 56 pages of the eponymous government act overlaid with sewn-in red and white beads: white for the settler government’s printed words, and red for the ground upon which they were imposed. Visually and symbolically, Indian Act masters the juxtaposition of invisibility and illumination that defines postmodernist redactions like Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing, redeploying it toward a discussion of settler/Indigenous relations sorely lacking from the canon. More importantly, however, Myre emphasizes the processes of personal and collective transformation required by reconciliation as a social project. Rather than framing the images as works of conceptual genius, her narrative of Indian Act’s creation foregrounds more than 200 diverse individuals’ participation in the laborious, but also invigorating, process of beading (in a September 15th public talk held in conjunction with the show, she even spoke of the catharsis of violently tearing into the legislation’s pages). This communitarian aspect of the 2002 project is highlighted in three 2014 prints, each titled Orison, that document the idiosyncratic thread patterns left on the backs of the Act’s pages by individual beaders.

Installation view, “Through Lines,” 2018, Koffler Gallery, Toronto. Courtesy Koffler Gallery, Toronto.

Where Myre traces redaction’s crossing from oppressive act to collaborative practice, Anishinaabe artist Maria Hupfield’s six photographic works (exhibited in Critical Distance’s separate exhibition space on Artscape Youngplace’s third floor) implicate the viewer directly in their unfoldings of information and identity. Appropriating photographs from Hupfield’s own 2007 series “Counterpoint,” these works cover one of the two figures in each original composition with a patch of grey felt, disrupting our engagement with what are otherwise big, bold and eminently consumable images. While “Counterpoint” dramatizes Hupfield’s misrecognition at the hands of broader cultural blindnesses, the interventions included in “Through Lines” restore her individuality by presenting her singularly within each scene. Yet, this restoration takes place only through new forms of conflict and resilience: while some pieces frame Hupfield against scene-destroying blocks of homogenous noise, others trace the contour of her fellow model with terrifying accuracy. In every case, however, Hupfield forces the viewer to account for their own navigation through the image. Where the spectacle of Indigenous women’s bodies is itself a form of erasure, personhood is always filtered through this interplay of visibility and disappearance.

Despite its stark subject matter, the predominant aesthetic in “Through Lines” is dauntlessly colourful. In turn, it activates the living presence of the viewer. Raafia Jessa’s installation of /’lo.kwi:/, 2016, wallpapers the gallery’s entranceway with multicoloured characters from its fictitious half-Arabic, half-Latin alphabet, situating the viewer more as an agent than a decoder of the utopian language world the work projects. Meanwhile, Michèle Pearson Clarke’s video work All That Is Left Unsaid, 2014, confronts us with our own out-of-placeness in a present marked by lack and loss. At first drawing the viewer in with its lush purple exhibition space and close, intimate framing of Audre Lorde in a 1995 documentary interview, the film soon pushes us back out, into our own hapless bodies, as it proceeds mechanically through clips of Lorde’s gestures and stutters—everything but her actual words. By replacing the momentous poet’s promise of verbal clarity with the abrasive texture of her absence (Lorde, like Clarke’s mother, died young of cancer), Clarke throws us into our harrowing responsibility to transform ourselves by our own volition.

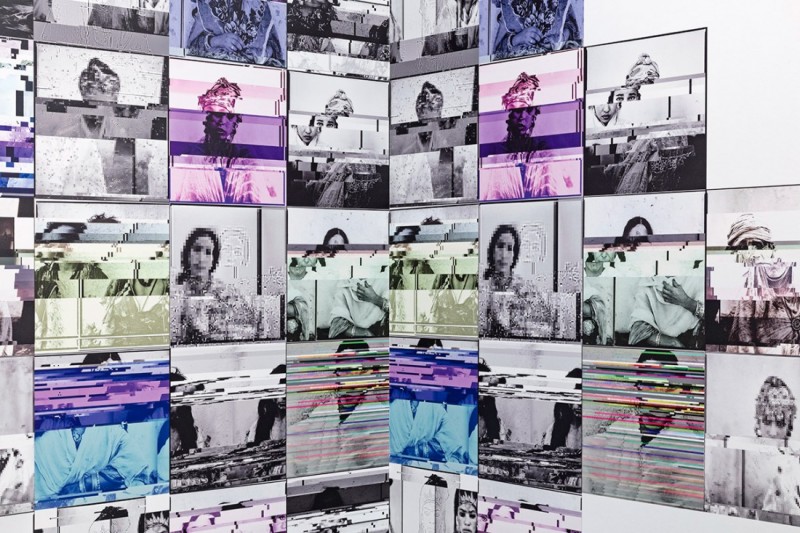

Leila Fatemi, Revealed/Reveiled , detail, 2018, digital print on adhesive vinyl, dimensions variable. Photo: Toni Hafkenschied. Courtesy Koffler Gallery, Toronto.

Although redaction is central to each of the exhibition’s works, the striking variety of its manifestations across “Through Lines” asserts that the technique cannot be reduced to a single material form. Like Myre and Hupfield, Leila Fatemi focuses on the act of covering up in Revealed/Reveiled, 2018, which uses digital image glitching to re-cover the Muslim Algerian women forced to unveil for French colonial photographer Marc Garanger’s Femmes Algeriennes, 1970. Meanwhile, Scott Benesiinaabandan and Lise Beaudry follow Clarke in composing through juxtapositions and cuts, collapsing their sources’ temporalities rather than layering over them spatially. Yet, Beaudry especially—in constructing her brilliant and haunting mural Maurice, 2018, out of shredded inkjet prints of family photos—reminds us that redaction is defined less by its objective form than by the subject who realizes, remembers, and desires alongside and in spite of it. Whenever reality isn’t wholly on view (which is, of course, always), we are the source of its through lines, on one end commemorating what has been taken away, on the other inventing what has never been there in the first place.

“Through Lines” was exhibited at the Koffler Gallery, Toronto, from September 13 to November 25, 2018.

John Nyman is a poet, critic, and scholar from Toronto.