Thomas Hirschhorn and Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle

“Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold,” Yeats wrote in his 1920 poem “The Second Coming.” It was the poet’s ultimate statement on the horrors of World War I and the perils of modernity. These famous phrases kept coming to mind as I visited the Power Plant’s shows in Toronto this spring: a resonant pairing of the Swiss-born artist Thomas Hirschhorn (showing his sprawling sculptural installation “Das Auge”) and Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle, who showed two works: his hypnotic installation Always After (The Glass House), a 2006 video projection picturing the cleanup of shattered architectural glass in a Mies van der Rohe building, and his sculptural installation Phantom Truck, 2007, a moody post-9/11 nocturne evoking imagined stores of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction. Taken together, Manglano-Ovalle and Hirschhorn offered an incisive and weirdly timely meditation on global mayhem.

At the time, things did indeed seem to be falling apart—for both the good and the bad. The Arab Spring was bringing the hope of peaceful and swift resolution to decades of political stagnation and corruption in the Middle East and North Africa (swift resolution has proved elusive), the tsunami in Japan was followed by the nuclear threat in Fukushima, the levees threatened to breach anew in Louisiana, and in Iceland, Mother Nature was up to her old sulphuric tricks again.

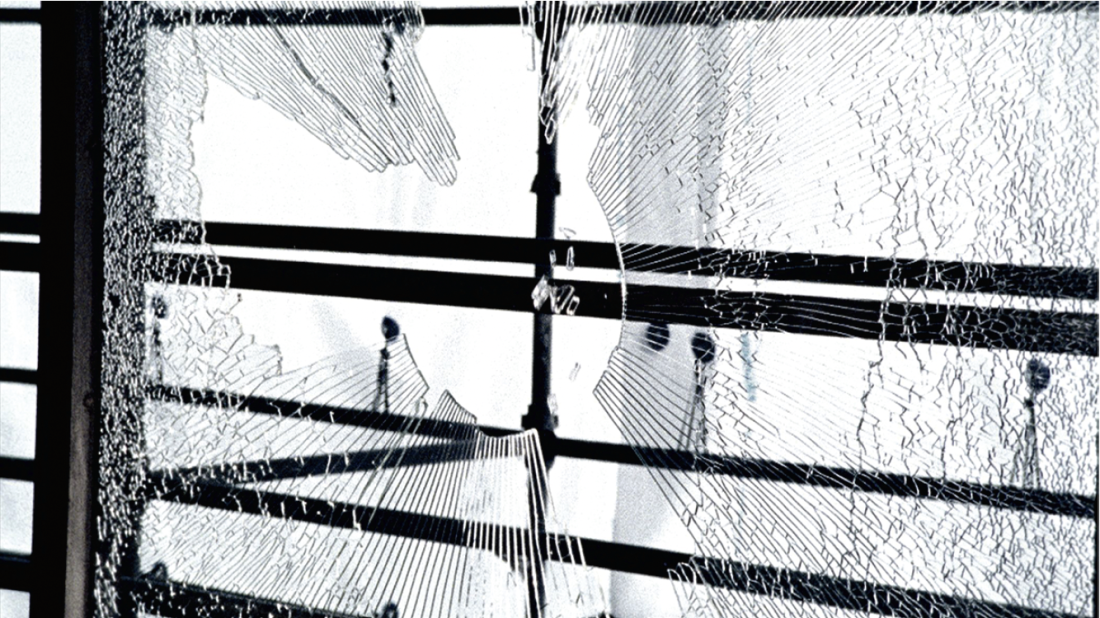

Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle, Always After (The Glass House), 2006, Super 16mm film transferred to HD video (still). Courtesy the artist and Donald Young Gallery, Chicago.

Things falling apart, shattering, coming asunder—these were the motifs that were playing out likewise in the Power Plant’s two galleries, but the artists’ visual languages could not have been more different. While Hirschhorn came off as the brilliant mad March hare of the apocalypse (plastering his installation with almost unbearably graphic images of human and animal dismemberment), Manglano-Ovalle’s mesmerizing slow motion Always After was a seductive and glittering study of destruction and transformation, while his Phantom Truck, exhibited in almost total darkness, left us puzzling after truth and trying to put together the pieces.

One of Thomas Hirschhorn’s signature materials is transparent packing tape, a temporary binding medium that one associates with moving day and rickety repair. It’s a material he uses in frantic abundance in “Das Auge,” in which images and texts from newspapers, the Internet, magazines and advertising are combined with found consumer goods, as well as paint, wire, Styrofoam and plywood—all bound together into a kind of provisional coherence. One enormous wall banner reads: The New Uncertainty, a phrase that sets the frame for perception.

Red is the signature colour here, a “blood dimmed tide” (to borrow from Yeats again) that Hirschhorn lays over the sculptural melee. Borrowing the traditional materials of the grade school project—bristol board, marker pens, Xeroxed pictures—he evokes our most primitive efforts at ordering knowledge.

Here, though, strange and disturbing collisions of imagery abound. Elevated on a runway that traverses the gallery space, a mock fashion show of female mannequins sport bloodied fur coats. Some of these figures wear animal masks to hide their faces. Are they protesting the harvesting of pelts or have they been targeted by animal rights advocates? It’s not clear. Everyone is implicated.

Installation views of Thomas Hirschhorn’s exhibition “Das Auge (The Eye),” 2008. Power Plant Gallery. Photograph: Steve Payne. Courtesy the Power Plant, Toronto.

Around them, Hirschhorn assembles rows of white plastic garden chairs, each one affixed with the face of an anonymous member of the public (cut out Xeroxed heads attached with more clear tape). Lined up in passive spectatorship in the compulsory seated position, they are doomed to bear witness but can never take action. Around them, fake igloos and Styrofoam ice floes are drenched in ersatz blood and brain mulch, the effluent of dozens of bullet-wounded mannequin heads and red splattered baby seals (stuffed animals of the airport gift-shop variety). These vie for our attention with Xeroxed photos of grotesque human injury, dismemberment and death in the world’s wartorn places. Above it all, a giant papier mâché eyeball looms from behind a balcony railing taking in the gory scene.

Critics of Hirschhorn have dismissed him as a sensationalist, indicting his dark humour as evidence of his insensitivity to human suffering. But that is to miss the point. Like John Heartfield, another caustic wit and a potent Dadaist forebearer, Hirschhorn rings the comic note in desperation. “Das Auge” invites us to see the common brutal fate of human beings engaged in conflict. Looking here, one glimpsed a tragic truth: in death, there are no good or bad victims. The freedom fighters cannot be distinguished from the fascists. There is just waste and torn flesh and the brute animal fact of our meaty, corporeal selves, which our intellectual selves would disavow. The butchered seals help to bring this home. Bereft of life and cognition, as carcasses they’re not so different from us. Plunging us face first into this reality, Hirschhorn makes us puzzle over our species’ signature capacity to fight to the death over our beliefs and our contested resources. This is what we do.

Manglano-Ovalle (who was born in Spain and now lives in Chicago) leaves us similarly humbled by the inexorable forces of history. In Always After, his camera lens takes in a site of demolition: Mies van der Rohe’s Crown Hall at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago, which he recorded on camera during its recent renovation. Push brooms sweep up glittering piles of broken glass (we cannot see the janitorial workers), and a thick sheet of glass disintegrates and falls to the floor in lazy slow motion. Elegantly clad men and women (we see just their ankles) drift up and down an adjacent staircase, touring the detritus. It sets you to thinking: Mies’s Modernist monument was built in the heyday of high hopes, when it was believed that good design and social equity were destined to advance hand in hand. More than a half century later, however, the wrecking ball is swinging. Gone are the utopian dreams and the architectural forms that expressed them. Instead, we find ourselves inhabiting new socio-political structures that we can’t yet understand.

Installation views of Thomas Hirschhorn’s exhibition “Das Auge (The Eye),” 2008. Power Plant Gallery. Photograph: Steve Payne. Courtesy the Power Plant, Toronto.

Manglano-Ovalle’s second work in the show, Phantom Truck, suggests a chief threat to that understanding: the media, with its inaccuracy and obfuscation (how bad is the nuclear fallout from Fukushima anyway?), its lazy bandwaggoneering, its complicity with power and its proficiency at engaging our darkest primal fears for the sake of profit. Here, the artist literally keeps us in the dark—in this case a sepulchral gallery space illuminated by only a few small windowpanes that glow red. (There’s that colour again.) Once my eyes adjusted I could just make out the contours of a giant truck loaded up with various storage containers—a menacing sculptural replica that conforms (the wall labels tell us) to Colin Powell’s verbal descriptions of the much-feared WMDs in Iraq, as he described them in his fateful United Nations testimony. Walking around this looming shape in the half-light, I found it was never possible to get a total sense of its scale and contours—a perfect experiential corollary to those traumatic days post-9/11 when certainties were so terrifyingly elusive.

I happened to see this show for the final time on the morning it was being disassembled. No longer shrouded in darkness, the truck was drenched in overhead artificial light as the crew worked to dismantle it. Not so frightening now, it looked like what it was—something big yet essentially unintimidating. “Surely some revelation is at hand,” Yeats wrote in “The Second Coming.” Turning on the lights, however, is not so easy in the real world. ❚

Thomas Hirshhorn’s “Das Auge” (The Eye) and Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle’s “Phantom Truck + Always After” were exhibited at the Power Plant in Toronto from March 11 to May 29, 2011.

Sarah Milroy is a Toronto-based writer.