Thinking through the Body

“My work has always operated in a space,” says filmmaker and writer Elian Mikkola, “where I can take things apart and try to put them together and understand myself through that process.” The archive of things the Canadian-based, Finnish-born artist subjects to their constructive dismantling is wideranging: MAN MADE, 2022, considers the collision between an embryonic aesthetic sensibility and an entrenched levelling of the imagination; Via Karelia, 2021, takes a family journey through a forced evacuation and return; Mascing, 2020, presents and questions masculine identity in the context of a wargame; and Magdaleena, 2019, examines the details of a childhood song, looking there for an explanation of adult trauma. What Mikkola has come to recognize is that these disconnected narratives have actually been a series of projects of disguised self-definition.

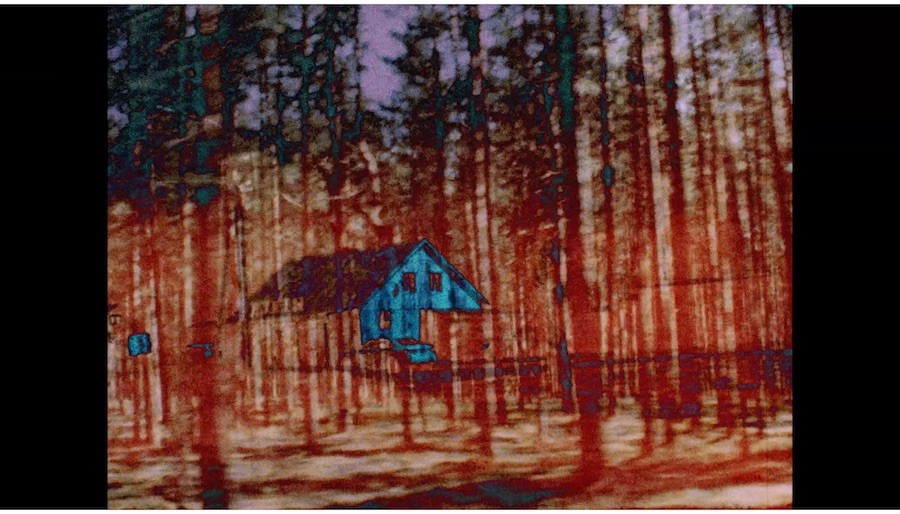

Elian Mikkola, Via Karelia, 2021, single-channel video, 16 mm to digital, 13 minutes. All images courtesy the artist.

Mascing uses as a narrative frame a VHS tape found in the home of their partner’s grandparents. It contained a war exercise recorded by the American military, and over the commentator’s jingoistic language, they splice in a film sequence of their doing weight training, running, self-administering a military haircut and finally applying some of that cut hair as a moustache and beard. They are constructing a soldier in an enactment that combines ridiculous satire and serious ritual. Their making of a soldier is a counterpoint to the language of the already-made soldiers. “I’m almost making fun but it is still something that I’m pulled to do when I’m shifting more towards a masculine representation. I am submitting myself to it because it’s a dialogue that I’m still dealing with quite a bit,” Mikkola says.

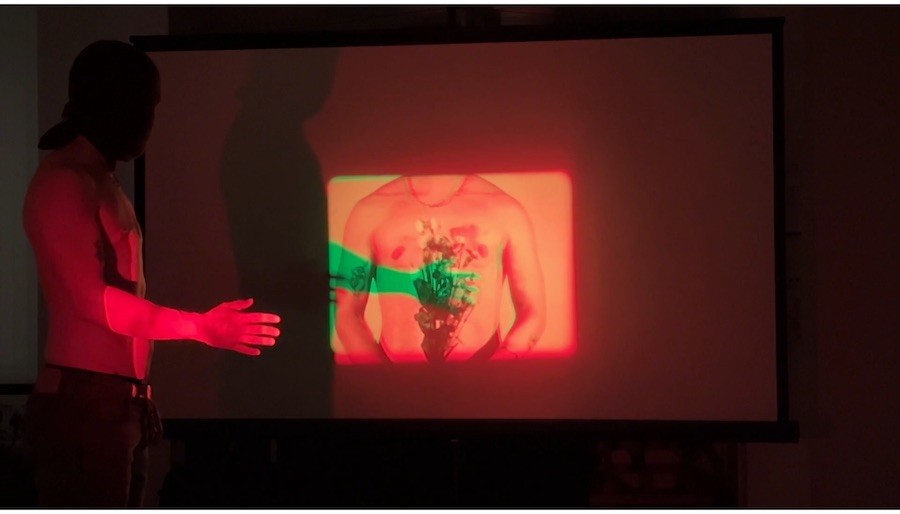

Elian Mikkola, Carcass, 2022, expanded cinema, 4-channel video, 16 mm to digital, 20-minute loop.

Elian Mikkola, Carcass, 2022, expanded cinema, 4-channel video, 16 mm to digital, 20-minute loop.

The mechanism for that persistent dialogue has been technology. In Based on True Stories, 2018, and recently in Twinklight, 2024, an expanded cinema in progress, we see a meta-film displaying the projectors and film strips that are the working apparatus of film imaging. For Mikkola, technology is both a tool and an obstruction; in Waves, 2017, flashing radiant light, reflecting coloured bars and image diffusion interrupt our appreciation of a dancer’s movement. A short piece like Milki Way, 2022, a site-specific installation that is one of the “Nipple Series,” turns a reconstructed nipple from gender-affirmation surgery into a super nova. If accepting that radical a shift in transformative scale is difficult, consider that Mikkola has also worked collaboratively in a project where they and another Regina artist dress up in bear costumes and project trans-positive messages onto the walls of public buildings, what Mikkola describes as a “playful act for a very simple mission.” The Holzer-like declarations are unambiguous: “Trans joy forever,” “All pronouns are valid” and “Trans women are WOMEN.” The performance is a declaration of, rather than a search for, identity.

Elian Mikkola, Magdaleena, 2019, single-channel video, 16 mm digital, 14 minutes.

Elian Mikkola, Magdaleena, 2019, single-channel video, 16 mm digital, 14 minutes.

Built into their practice is a moral code; Mikkola is concerned to convert the material of filmmaking into an ethics of filmmaking. They use eco-processing black and white film; the decision is ecologically sustainable at the same time that it engages them in an aesthetics of unpredictability: “When I worked with expired colour stock, I was curious to see what the colour is like when it doesn’t perform to its expected potential.”

Carcass, 2022, a four-channel synchronized projection shown at Neutral Ground in Regina, functions as faux anthropology. The focus is on presenting “The Posthistoric Queer” through an arrangement of dramatically lit tools and bones, as if they were objects from a fictional archaeological dig. The kinetic component in the exhibition is a 20-minute-long film, split across four screens, that shows the Carcass rising from the earth, crawling into the sea and then back onto a mountainside. We are not sure of its fate. The story was written in Finland in 2020 during the first year of the pandemic at a time when Mikkola “started making decisions about my own body and about transitioning. I was looking at my body in a fictional way and trying to understand where it was going, whether it was dying or whether it was going to survive.”

Elian Mikkola, MAN MADE, 2022, single-channel video, 16 mm to digital, 8 minutes.

Carcass not only fictionalizes the body but, through the delicacy of the script, eroticizes it as well. The sea is a significant character in the film and their narrative describing the Carcass is a seductive, teasing voice-over. “Poor Carcass. Just lays and lets the waves hit through its body, one after another. Cold water intrudes through the toes, continues towards the knees, touches the inner surface of the thighs and then stops. Hesitates for a moment. And then retreats along the same pathway.” Among the most effective moments in the film is one that shows the Carcass, covered in transparent plastic, getting up and walking across the screen and out of frame, like Goya’s Colossus. Mikkola has remarked that in the figure of the Carcass, they wanted “to create something almost painterly and still,” and the figure’s mesmerizing slow mobility captures that quality. “I think through my body a lot,” they say, “but in addition I relate technology with the body. So it becomes kind of robotic, like an avatar of the flesh body. I want to put them in dialogue so that they resonate. I’m finding that connection point.”

Elian Mikkola, Twinklight, under development for 2025, expanded cinema performance, 16 mm.

Elian Mikkola, Twinklight, under development for 2025, expanded cinema performance, 16 mm.

The discovery of that connection is generative, and Mikkola’s declaration of self is persistent. “I think when it’s the only way of life that you know, it’s not really about it being easy or difficult. It will always be a part of how I think in this world. Gender is an ongoing process for me. There is no other way in. At this point, I feel very comfortable in my own skin.” ❚